Chūshingura

Chūshingura (忠臣蔵, The Treasury of Loyal Retainers) is the title given to fictionalized accounts in Japanese literature, theatre, and film that relate to the historical incident involving the Forty-seven Ronin and their mission to avenge the death of their master, Asano Naganori. Including the early Kanadehon Chūshingura (仮名手本忠臣蔵), the story has been told in kabuki, bunraku, stage plays, films, novels, television shows and other media. With ten different television productions in the years 1997–2007 alone, Chūshingura ranks among the most familiar of all historical stories in Japan.

Historical events

The historical basis for the narrative begins in 1701. The ruling shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi placed Asano Takumi-no-kami Naganori, the daimyo of Akō, in charge of a reception of envoys from the Imperial Court in Kyoto. He also appointed the protocol official (kōke) Kira Kōzuke-no-suke Yoshinaka to instruct Asano in the ceremonies. On the day of the reception, at Edo Castle, Asano drew his short sword and attempted to kill Kira. His reasons are not known, but many purport that an insult may have provoked him. For this act, he was sentenced to commit seppuku, but Kira did not receive any punishment. The shogunate confiscated Asano's lands (the Akō Domain) and dismissed the samurai who had served him, making them rōnin.

Nearly two years later, Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, who had been a high-ranking samurai in the service of Asano, led a group of forty-six/forty-seven of the ronin (some discount the membership of one for various reasons). They broke into Kira's mansion in Edo, captured and executed Kira, and laid his head at the grave of Asano at Sengaku-ji. They then turned themselves in to the authorities, and were sentenced to commit seppuku, which they all did on the same day that year. Ōishi is the protagonist in most retellings of the fictionalized form of what became known as the Akō incident, or, in its fictionalized form, the Treasury of Loyal Retainers (Chūshingura).[1][2]

In 1822, the earliest known account of the Akō incident in the West was published in Isaac Titsingh's posthumous book, Illustrations of Japan.[3]

Religious significance

In the story of the 47 Ronin, the concept of chuushin gishi is another interpretation taken by some. Chuushin gishi is usually translated as “loyal and dutiful samurai”. However, as John Allen Tucker [4] points out that definition glosses over the religious meaning behind the term. Scholars during that time used that word to describe people who had given their lives for a greater cause in such a way that they deserved veneration after death. Such people were often entombed or memorialized at shrines.

However, there is a debate on whether they even should be worshiped and how controversial their tombs at Sengakuji are. Tucker raises a point in his article that the ronin were condemned as ronin, but then in the end their resting places are now honored. In other words, it is like those that regarded the ronin as chuushin gishi were questioning the decision of the Bakufu (the "Shogunate," the authorities who declared them ronin). Perhaps even implying that the Bakufu had made a mistake. Those recognizing the ronin as chuushin gishi were really focusing on the basics of samurai code where loyalty to your master is their ultimate and most sacred obligation.

In Chinese philosophy, Confucius used to say that the great ministers served their rulers the moral way. Early Confucianism emphasized loyalty, the moral way and objection and legitimate execution of wrongdoers. Chuushin gishi is interpreted as almost a blind loyalty to your master. In the Book of Rites, something similar to chuushin gishi is mentioned which is called zhongchen yishi. Interpretations of the passage from the Book identified those who would sacrifice themselves in the name of duty should live on idealized. However, there were also those that agreed on condemnation of the ronin as criminals like Ogyuu Sorai. So definitely there was controversy revolving around the legitimacy of the ronin's actions. Sorai, Satou Naokata and Dazai Shundai were some of those who believed that the ronin were just criminals and had no sense of righteousness. Because they did violate the law by killing Kira Yoshinaka.

Confucianism and the deification of the ronins collision is something that is very important to the way to understanding Bakufu law. Confucian classics and the Bakufu law may have seemed to compliment each other to allow revenge. Hayashi Houkou claims that the idolization of the ronin may have been allowed because their actions matched with the Chinese loyalists. Also suggesting that only by killing themselves would they be able to claim their title as chuushin gishi. There then, Hokou summarized that there might have been a correlation between the law and the lessons put forth in Confucian classics.

Actually during the seventeenth century there was a system of registered vendettas. This meant that people could avenge a murder of a relative, but only after their plans strictly adhered to legal guidelines. However, the Akou vendetta didn't adhere to this legalized system. Thus, they had to look to Confucian texts to justify their vendetta. Chuushin gishi is something that cannot be looked on lightly in regards to this story because it is the main idea in this story. Loyalty and duty to one's master as a retainer is everything in the story of the 47 ronin.

Being able to draw Confucianist values from this story is no coincidence, it is said that Asano was a Confucian. So it would only seem natural that his retainers would practice the same thing. Their ultimate sacrifice for their master is something that is held in high regard in Confucianism because they are fulfilling their responsibility to the fullest extent. There is nothing more after that kind of sacrifice. At that point the warriors have given their everything to their master. That type of devotion is hard to contest as something other than being a chuushin gishi.

Bunraku(文楽)

The puppet play based on these events was entitled Kanadehon Chūshingura and written by Takeda Izumo (1691–1756),[5] Miyoshi Shōraku (c. 1696 – 1772)[6] and Namiki Senryū (1695 – c. 1751).[7] It was first performed in August 1748 at the Takemoto-za theatre in the Dōtonbori entertainment district in Osaka, and an almost identical kabuki adaptation appeared later that year. The title means "Kana practice book Treasury of the loyal retainers." The "kana practice book" aspect refers to the coincidence that the number of ronin matches the number of kana, and the play portrayed the ronin as each prominently displaying one kana to identify him. The forty-seven rōnin were the loyal retainers of Asano; the title likened them to a warehouse full of treasure. To avoid censorship, the authors placed the action in the time of the Taiheiki (a few centuries earlier), changing the names of the principals. The play is performed every year in both the bunraku and kabuki versions, though more often than not it is only a few selected acts which are performed and not the entire work.

-

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, The Monster's Chūshingura (Bakemono Chūshingura), ca. 1836, Princeton University Art Museum, Acts 9–11 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act nine at top right, act ten at bottom right, act eleven, scene 1, at top left, act eleven, scene 2 at bottom left

-

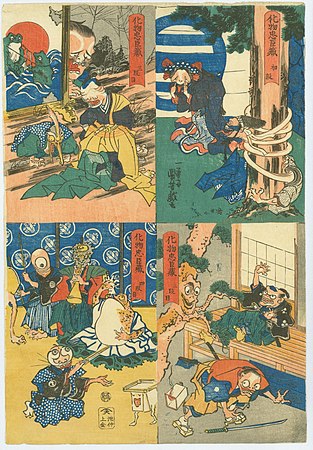

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, The Monster's Chūshingura (Bakemono Chūshingura), ca. 1836, Princeton University Art Museum, Acts 5–8 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act five at top right, act six at bottom right, act seven at top left, act eight at bottom left

-

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, The Monster's Chūshingura (Bakemono Chūshingura), ca. 1836, Princeton University Art Museum, Acts 1–4 of the Kanadehon Chūshingura with act one at top right, act two at bottom right, act three at top left, act four at bottom left

Kabuki(歌舞伎)

Sections of the following synopsis of Kanadehon Chūshingura are reproduced by permission from the book A Guide to the Japanese Stage by Ronald Cavaye, Paul Griffith and Akihiko Senda, published by Kodansha International, Japan:

Kanadehon Chūshingura (“The Treasury of Loyal Retainers”) is based on a true incident which took place between 1701 and 1703. To avoid shogunate censorship, the authors set the play in the earlier Muromachi period (1333–1568) and the names of the characters were altered. However some names sounded similar and those with knowledge knew what they were referring to in reality. For example the real person Ōishi Kuranosuke was changed to Ōboshi Yuranosuke. The play therefore fuses fiction and fact.

The central story concerns the daimyō Enya Hangan, who is goaded into drawing his sword and striking a senior lord, Kô no Moronō (Note: although the furigana for Moronō's name is Moronao, the pronunciation is Moronō). Drawing one’s sword in the shogun’s palace was a capital offense and so Hangan is ordered to commit seppuku, or ritual suicide by disembowelment. The ceremony is carried out with great formality and, with his dying breath, he makes clear to his chief retainer, Ōboshi Yuranosuke, that he wishes to be avenged upon Moronô.

Forty-seven of Hangan’s now masterless samurai or rōnin bide their time. Yuranosuke in particular, appears to give himself over to a life of debauchery in Kyoto’s Gion pleasure quarters in order to put the enemy off their guard. In fact, they make stealthy but meticulous preparations and, in the depths of winter, storm Moronō’s Edo mansion and kill him. Aware, however, that this deed is itself an offense, the retainers then carry Moronō’s head to the grave of their lord at Sengaku-ji temple in Edo, where they all commit seppuku.

Act I, Tsurugaoka kabuto aratame (“The Helmet Selection at Hachiman Shrine”)

This play has a unique opening, in which the curtain is pulled open slowly over several minutes, accompanied by forty-seven individual beats of the ki, one for each of the heroic rōnin. Gradually, the actors are revealed in front of the Hachiman Shrine in Kamakura slumped over like lifeless puppets. As the gidayū narrator speaks the name of each character he comes to life. Lord Moronō’s evil nature is immediately demonstrated by his black robes and the furious mie pose which he strikes when his name is announced. He is hostile to the younger, inexperienced lords. They have all gathered to find and present a special helmet at the shrine and it is Hangan’s wife, Kaoyo, who is the one to identify it. When the ceremony is over and he is eventually left alone with Kaoyo, Moronō propositions her but she rejects his amorous advances.

Act II, The Scriptorium of the Kenchōji Temple

When Act II is performed as Kabuki it is often given in a later version, first performed by Ichikawa Danjūrō VII (1791–1859), and entitled “The Scriptorium of the Kenchōji Temple”. A performance of Act II is extremely rare, even “complete” (tōshi kyōgen) performances almost never include it. The original puppet and Kabuki scripts of Act II are similar and the story is as follows - The act takes place in the mansion of the young daimyō, Momonoi Wakasanosuke. His chief retainer, Kakogawa Honzō, admonishes the servants for gossiping about the humiliation of their master by Moronō at the previous day’s ceremony at the Tsurugaoka shrine. Even Honzō’s wife, Tonase, and daughter, Konami, speak of it. Ōboshi Rikiya, Konami’s betrothed and the son of Enya Hangan’s chief retainer, Ōboshi Yuranosuke, arrives with a message that Moronō has commanded that both Hangan and Wakasanosuke appear at the palace by four in the morning in order to prepare the ceremonies for the Shogun’s younger brother whom they are to entertain. Wakasanosuke hears the message and dismisses them all apart from Honzō. He speaks of the insults which he suffered and his determination to take his revenge. He decides to kill Moronō tomorrow even if such a rash and illegal act brings about the eradication of his household. Surprisingly, the older and wiser Honzō sympathises with him and, as a symbol that Wakasanosuke should go through with the attack, he cuts off the branch of a bonsai pine tree. It is one o’clock in the morning and Wakasanosuke goes off to bid farewell to his wife for the last time. As soon as his master leaves Honzō calls urgently for his horse. Forbidding his wife and daughter from disclosing his intentions, he gallops off to Moronō’s mansion to prevent what would be a disaster both for his master and his master’s house.

Act III, scene 2, Matsu no rōka (“The Pine Corridor in the Shogun’s Palace”)

This is the scene which seals Hangan’s fate. Offended by Kaoyo’s rebuff, Moronō hurls insults at Hangan, accusing him of incompetence and of being late for his duties. Hangan, he says, is like a little fish: he is adequate within the safe confines of a well (his own little domain), but put him in the great river (the shogun’s mansion in the capital) and he soon hits his nose against the pillar of a bridge and dies. Unable to bear the insults any longer, Hangan strikes Moronō but, to his eternal chagrin, is restrained from killing him by Wakasanosuke's retainer Kakogawa Honzō.

Act IV, scene 1, Enya yakata no ba (“Enya Hangan’s Seppuku”)

Hangan is ordered to commit seppuku and his castle is confiscated. The emotional highlight of this scene is Hangan’s death. The preparations for the ceremony are elaborate and formal. He must kill himself on two upturned tatami mats which are covered with a white cloth and have small vases of anise placed at the four corners. He is dressed in the shini-shōzoku, the white kimono worn for death. The details of the seppuku were strictly prescribed: the initial cut is under the left rib-cage, the blade is then drawn to the right and, finally, a small upward cut is made before withdrawing the blade. Hangan delays as long as he can, however, for he is anxious to have one last word with his chief retainer, Yuranosuke. At the last moment, Yuranosuke rushes in to hear his lord’s dying wish to be avenged on Moronô. Hangan is left to despatch himself by cutting his own jugular vein.

This act is a tosan-ba, or "do not enter or leave" scene, which means the audience was not allowed to enter or leave while it was played, the atmosphere had to be completely silent and nothing was allowed to disturb the suicide scene.

Act IV, scene 2, Uramon (“The Rear Gate of the Mansion”)

Night has fallen and Yuranosuke, left alone, bids a sad farewell to their mansion. He holds the bloody dagger with which his lord killed himself and licks it as an oath to carry out his lord’s dying wish. The curtain closes and a lone shamisen player enters to the side of the stage, accompanying Yuranosuke’s desolate exit along the hanamichi.

Interact, Michiyuki tabiji no hanamuko (Ochiudo) (“The Fugitives”)

This michiyuki or “travel-dance” was added to the play in 1833 and is very often performed separately. The dance depicts the lovers Okaru and Kanpei journeying to the home of Okaru’s parents in the country after Hangan’s death. Kanpei was the retainer who accompanied Hangan to the shogun’s mansion and he is now guilt ridden at his failure to protect his lord. He would take his own life to atone for his sin, but Okaru persuades him to wait. The couple are waylaid by the comical Sagisaki Bannai and his foolish men. They are working for Lord Moronō but Kanpei easily defeats them and they continue on their way.

Act V, scene 1, Yamazaki kaidō teppō watashi no ba (“The Musket Shots on the Yamazaki Highway”)

While only a peripheral part of the story, these two scenes are very popular because of their fine staging and dramatic action. Kanpei is now living with Okaru’s parents and is desperate to join the vendetta. On a dark, rainy night we see him out hunting wild boar. Meanwhile, Okaru has agreed that her father, Yoichibei, sell her into prostitution in Kyoto to raise money for the vendetta. On his way home from the Gion pleasure quarter with half the cash as a down payment, Yoichibei is, however, murdered and robbed by Sadakurô, the wicked son of Kudayū, one of Hangan’s retainers. Sadakurō is dressed in a stark black kimono and, though brief, this role is famous for its sinister and blood curdling appeal. Kanpei shoots at a wild boar but misses. Instead, the shot hits Sadakurō and, as he dies, the blood drips from Sadakurō’s mouth onto his exposed white thigh. Kanpei finds the body but cannot see who it is in the darkness. Hardly believing his luck, he discovers the money on the body, and decides to take it to give to the vendetta.

Act VI, Kanpei seppuku no ba (“Kanpei’s Seppuku”)

Yoichibei’s murder is discovered and Kanpei, believing mistakenly that he is responsible, commits seppuku. The truth, however, is revealed before he draws his last breath and, in his own blood, Kanpei is permitted to add his name to the vendetta list.

Act VII, Gion Ichiriki no ba (“The Ichiriki Teahouse at Gion”)

This act gives a taste of the bustling atmosphere of the Gion pleasure quarter in Kyoto. Yuranosuke is feigning a life of debauchery at the same teahouse to which Okaru has been indentured. Kudayū, the father of Sadakurō, arrives. He is now working for Moronō and his purpose is to discover whether Yuranosuke still plans revenge or not. He tests Yuranosuke’s resolve by offering him food on the anniversary of their lord’s death when he should be fasting. Yuranosuke is forced to accept. Yuranosuke’s sword – the revered symbol of a samurai – is also found to be covered in rust. It would appear that Yuranosuke has no thoughts of revenge. But still unsure, Kudayū hides under the veranda. Now believing himself alone, Yuranosuke begins to read a secret letter scroll about preparations for the vendetta. On a higher balcony Okaru comes out to cool herself in the evening breeze and, noticing Yuranosuke close by, she also reads the letter reflected in her mirror. As Yuranosuke unrolls the scroll, Kudayū, too, examines the end which trails below the veranda. Suddenly, one of Okaru’s hairpins drops to the floor and a shocked Yuranosuke quickly rolls up the scroll. Finding the end of the letter torn off, he realises that yet another person knows his secret and he must silence them both. Feigning merriment, he calls Okaru to come down and offers to buy out her contract. He goes off supposedly to fix the deal. Then Okaru’s brother Heiemon enters and, hearing what has just happened, realises that Yuranosuke actually intends to keep her quiet by killing her. He persuades Okaru to let him kill her instead so as to save their honour and she agrees. Overhearing everything, Yuranosuke is now convinced of the pair’s loyalty and stops them. He gives Okaru a sword and, guiding her hand, thrusts it through the floorboards to kill Kudayū.

The main actor has to convey a wide variety of emotions between a fallen, drunkard ronin and someone who in reality is quite different since he is only faking his weakness. This is called hara-gei or "belly acting", which means he has to perform from within to change characters. It is technically difficult to perform and takes a long time to learn, but once mastered the audience takes up on the actor's emotion.

Emotions are also expressed through the colours of the costumes, a key element in kabuki. Gaudy and strong colours can convey foolish or joyful emotions, whereas severe or muted colours convey seriousness and focus.

Act VIII, Michiyuki tabiji no yomeiri (“The Bride’s Journey”)

When Enya Hangan drew his sword against the evil Moronō within the shogun’s palace, it was Kakogawa Honzō who held him back, preventing him from killing the older lord. Honzō’s daughter, Konami, is betrothed to Yuranosuke’s son, Rikiya, but since that fateful event the marriage arrangements have been stalled, causing much embarrassment to the girl. Not prepared to leave things as they are, Honzō’s wife, Tonase, resolves to deliver Konami to Yuranosuke’s home in order to force the marriage. This act takes the form of a michiyuki dance in which Tonase leads her stepdaughter along the great Tōkaidō Highway, the main thoroughfare linking Edo in the east with Kyoto in the west. On the way, they pass a number of famous sites such as Mt. Fuji and, as a marriage procession passes by, Konami watches enviously, thinking that in better times she herself would have ridden in just such a grand palanquin. Tonase encourages her daughter, telling her of the happiness to come once she is wed.

Act IX, Yamashina kankyo no ba (“The Retreat at Yamashina”)

Set in the depths of winter, Kakogawa Honzō’s wife Tonase, and daughter Konami, arrive at Yuranosuke’s home in Yamashina near Kyoto. Yuranosuke’s wife is adamant that after all that has happened there can be no possibility of marriage between Konami and Rikiya. In despair, Tonase and Konami decide to take their own lives. Just then, Honzō arrives disguised as a wandering priest. To atone for his part in restraining Hangan from killing Moronō, he deliberately pulls Rikiya’s spear into his own stomach and, dying, gives Yuranosuke and Rikiya a plan of Moronō’s mansion in Edo.

Act X, Amakawaya Gihei Uchi no ba - (“The House Amakawaya Gihei”)

Act X is only rarely performed but provides a realistic interim (performed in the sewamono style) between Yuranosuke setting out at the end of Act IX and the final vendetta. The action takes place at the premises of Amakawaya Gihei, a merchant who lives in the port of Sakai, near Osaka. Yuranosuke has entrusted Gihei with the purchase and shipment to Kamakura of all the weapons, armour and other equipment which they will need for the vendetta. Knowing that he may be linked to the vendetta, Gihei has been preparing by dismissing his staff so that they would not be aware of what he was doing. He has even sent his wife, Osono, to her father’s so that she would be out of the way. The act usually opens with some of the boatmen discussing the loading of the chests and the weather and, as they go off, Gihei’s father-in-law, Ryōchiku, comes, demanding a letter of divorce so that he can marry Osono off to another man. Gihei agrees, thinking that his wife has betrayed him. After Ryōchiku’s departure, law officers arrive and accuse Gihei of being in league with Hangan’s former retainers. Gihei refuses to allow them to open one of the chests of weapons and armour, even threatening to kill his own son to allay their suspicions. Suddenly Yuranosuke himself appears and confesses that the law officers are, in fact, members of the vendetta and that he sent them to test Gihei’s loyalty. He praises Gihei’s resolution and commitment to their cause. As they all go off to a back room for a celebratory drink of sake, Gihei’s wife, Osono arrives, wishing both to return the letter of divorce, which she has stolen from her father, and to see their child. Gihei, however, torn between his love for his wife and his duty to Yuranosuke reluctantly forces her to leave. Shut outside, she is attacked in the dark by two men who steal her hair pins and combs and cut off her hair. Yuranosuke and his men reappear and, about to depart, place some gifts for Gihei on an open fan. The gifts turn out to be Osono’s shorn hair and ornaments. Yuranosuke had his men attack her and cut her hair to that her father would be unable to marry her off. No one would take a wife with hair as short as a nun’s. In hundred days, he says, her hair will grow back and she can be reconciled with her husband, Gihei. By then, Yuranosuke and his men will also have achieved their goal. Gihei and Osono, overawed by his kindness, offer their deepest thanks. Yuranosuke and his men depart for their ship.

Act XI, Koke uchiiri no ba (“The Attack on Moronô’s Mansion”)

The final act takes place at Moronō’s mansion on a snowy night. The attack is presented in a series of tachimawari fight scenes before Moronō is finally captured and killed.

The play became very popular and was depicted in many ukiyo-e prints. A large number of them are in the collection of the Waseda University Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum.[8]

Films, television dramas, and other productions

December is a popular time for performances of Chūshingura. Because the break-in occurred in December (according to the old calendar), the story is often retold in that month.

Films

The history of Chūshingura on film began in 1907, when one act of a kabuki play was released. The first original production followed in 1908. Onoe Matsunosuke played Ōishi in this ground-breaking work.

The story was adapted for film again in 1928. This version, Jitsuroku Chushingura, was made by film-maker Shōzō Makino to commemorate his 50th birthday. Parts of the original film were destroyed when fire broke out during the production. However, these sequences have been restored with new technology.

A Nikkatsu film retold the events to audiences in 1930. It featured the famous Ōkōchi Denjirō in the role of Ōishi. Since then, three generations of leading men have starred in the role. Younger actors play Asano, and the role of Aguri, wife (and later widow) of Asano, is reserved for the most beautiful actresses. Kira, who was over sixty at his death, requires an older actor. Ōkōchi reprised the role in 1934. Other actors who have portrayed Ōishi in film include Bandō Tsumasaburō (1938), and Kawarasaki Chōjūrō IV (1941).

In 1941 the Japanese military commissioned director Kenji Mizoguchi (Ugetsu) to make The 47 Ronin. They wanted a ferocious morale booster based upon the familiar rekishi geki ("historical drama") of "The Loyal 47 Ronin". Instead, Mizoguchi chose for his source Mayama Chushingura, a cerebral play dealing with the story. The 47 Ronin was a commercial failure, having been released in Japan one week before the Attack on Pearl Harbor. The Japanese military and most audiences found the first part to be too serious, but the studio and Mizoguchi both regarded it as so important that Part Two was put into production, despite Part One's lukewarm reception. The film was celebrated by foreign scholars who saw it in Japan; it was not shown in America until the 1970s.

During the occupation of Japan, the GHQ banned performances of the story, charging them with promoting feudal values. Under the influence of Faubion Bowers, the ban was lifted in 1947. In 1952, the first film portrayal of Ōishi by Chiezō Kataoka appeared; he took the part again in 1959 and 1961. Matsumoto Kōshirō VIII (later Hakuō), Ichikawa Utaemon, Ichikawa Ennosuke II, Kinnosuke Yorozuya, Ken Takakura and Masahiko Tsugawa are among the most noteworthy actors to portray Ōishi.

The story was told again in the 1962 Toho production by the acclaimed director Hiroshi Inagaki and titled Chushingura: Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki. The actor Matsumoto Kōshirō starred as Chamberlain Ōishi Kuranosuke. The actress Setsuko Hara retired following her appearance as Riku, wife of Ōishi.

The Hollywood film 47 Ronin by Universal is a fantasy epic, with Keanu Reeves as an Anglo-Japanese who joins the samurai in their quest for vengeance against Lord Kira, who is aided by a fictitious shape-shifting witch. It co-stars many prominent Japanese actors including Hiroyuki Sanada, Tadanobu Asano, Kô Shibasaki, Rinko Kikuchi, Jin Akanishi, and Togo Igawa. The film was originally scheduled to be released on November 21, 2012, then moved to February 8, 2013, due to creative differences between Universal and director Carl Rinsch, requiring the inclusion of additional scenes and citing the need for work on the 3D visual effects. It was later postponed to December 25, 2013, to account for the reshoots and post-production. Consistently negative film reviews of this film rendition considered it to have almost nothing in common with the original play.

Television dramas

The 1964 NHK Taiga drama Akō Rōshi was followed by no fewer than 21 television productions of Chūshingura. Toshirō Mifune starred in the 1971 Daichūshingura on NET, and Kinnosuke Yorozuya crossed over from film to play the same role in 1979, also on NET. Tōge no Gunzō, the third NHK Taiga drama on the subject, starred Ken Ogata, and renowned director Juzo Itami appeared as Kira. In 2001 Fuji TV made a four-hour special of the story starring Takuya Kimura as Horibe Yasubei (one of the Akō ronin) and Kōichi Satō as Ōishi Kuranosuke, called Chūshingura 1/47 . Kōtarō Satomi, Matsumoto Kōshirō IX, Beat Takeshi, Tatsuya Nakadai, Hiroki Matsukata, Kinya Kitaōji, Akira Emoto, Akira Nakao, Nakamura Kanzaburō XVIII, Ken Matsudaira, and Shinichi Tsutsumi are among the many stars to play Ōishi. Hisaya Morishige, Naoto Takenaka, and others have portrayed Kira. Izumi Inamori starred as Aguri (Yōzeiin), the central character in the ten-hour 2007 special Chūshingura Yōzeiin no Inbō.

The 1927 novel by Jirō Osaragi was the basis for the 1964 Taiga drama Akō Rōshi. Eiji Yoshikawa, Seiichi Funahashi, Futaro Yamada, Kōhei Tsuka, and Shōichirō Ikemiya have also published novels on the subject. Maruya Saiichi, Motohiko Izawa, and Kazuo Kumada have written criticisms of it.

An episode of the tokusatsu show Juken Sentai Gekiranger features its own spin on the Chūshingura, with the main heroes being sent back in time and Kira having been possessed by a Rin Jyu Ken user, whom they defeat before the Akō incident starts, and thus not interfering with it.

Ballet

The ballet choreographer Maurice Béjart created a ballet work called "The Kabuki" based on the Chushingura legend in 1986, and it has been performed more than 140 times in 14 nations worldwide by 2006.

Opera

The story was turned into an opera, Chūshingura, by Shigeaki Saegusa in 1997.

Popular music

"Chushingura" is the name of a song by Jefferson Airplane from its Crown of Creation album.

Books

Jorge Luis Borges' 1935 short story "The Uncivil Teacher of Court Etiquette Kôtsuké no Suké" (in A Universal History of Iniquity) is a retelling of the Chushingura story, drawn from A.B. Mitford's Tales of Old Japan (London, 1912).

A graphic novel/manga version, well researched and close to the original story, has been written by Sean Michael Wilson and illustrated by Japanese artist Akiko Shimojima: The 47 Ronin: A Graphic Novel (2013).

A limited comic book series based on the story entitled 47 Ronin, written by Dark Horse Comics publisher Mike Richardson, illustrated by Usagi Yojimbo creator Stan Sakai and with Lone Wolf and Cub writer Kazuo Koike as an editorial consultant, was released by Dark Horse Comics in 2013.

See also

References

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric et al. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia, p. 129.

- ^ Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Forty-Seven Ronin: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Edition. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQGLB8; Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Forty-Seven Ronin: Utagawa Kuniyoshi Edition. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQM8II

- ^ Screech, Timon. Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779–1824, p. 91.

- ^ Tucker, John A. “Rethinking the Akou Ronin Debate: The Religious Significance of Chuushin Gishi,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1/ 2 (Spring 1999): 1-37.

- ^ Nussbaum, p. 938.

- ^ Nussbaum, p. 652.

- ^ Nussbaum, p. 696.

- ^ http://www.columbia.edu/~hds2/chushingura/exhibition/pt1.html

- Bibliography

- Brandon, James R. "Myth and Reality: A Story of Kabuki during American Censorship, 1945-1949," Asian Theatre Journal, Volume 23, Number 1, Spring 2006, pp. 1-110.

- Chūshingura (in Japanese) retrieved January 6, 2006

- Cavaye, Ronald, Paul Griffith and Akihiko Senda. (2005). A Guide to the Japanese Stage. Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2987-4

- 新井政義(編集者)『日本史事典』。東京:旺文社 1987 (p. 87)

- 竹内理三(編)『日本史小辞典』。東京:Kadokawa Shoten 1985 (pp.349–350).

- Chushingura at IMDB

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Forty-Seven Ronin: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi Edition. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQGLB8

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2012). Forty-Seven Ronin: Utagawa Kuniyoshi Edition. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B00ADQM8II

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

- Screech, Timon. (2006). Secret Memoirs of the Shoguns: Isaac Titsingh and Japan, 1779-1822. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1720-0 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-203-09985-8 (electronic)