Chlamydia

| Chlamydia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious disease, gynecology, urology |

Chlamydia infection is a common sexually transmitted infection in humans caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. The term Chlamydia infection can also refer to infection caused by any species belonging to the bacterial family Chlamydiaceae. C. trachomatis is found only in humans. Chlamydia is a major infectious cause of human genital and eye disease. Chlamydia conjunctivitis or trachoma is a common cause of blindness worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that it accounted for 15% of blindness cases in 1995, but only 3.6% in 2002.[1]

Chlamydia can be spread during vaginal, anal, or oral sex, and can be passed from an infected mother to her baby during childbirth. Between half and three-quarters of all women who have a chlamydial infection of the cervix have an inflamed cervix without symptoms and may not realize they are infected. In men, infection by C. trachomatis can lead to inflammation of the penile urethra causing a white discharge from the penis with or without a burning sensation during urination. Occasionally, the condition spreads to the upper genital tract in women (causing pelvic inflammatory disease) or to the epididymis in men (causing inflammation of the epididymis). C. trachomatis is naturally found living only inside human cells.

Chlamydia infection can be effectively cured with antibiotics. If left untreated, chlamydial infections can cause serious reproductive and other health problems with both short-term and long-term consequences. Research is ongoing in the prevention of this infection.

Chlamydia infection is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide. In 2013 about 141 million cases occurred.[2] In the United States about 1 million individuals are infected with chlamydia.[3] The word chlamydia is from the Greek, χλαμύδα meaning "cloak".

Signs and symptoms

Genital disease

Women

Chlamydial infection of the neck of the womb (cervicitis) is a sexually transmitted infection which is asymptomatic for 50–70% of women infected with the disease. The infection can be passed through vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Of those who have an asymptomatic infection that is not detected by their doctor, approximately half will develop pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), a generic term for infection of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and/or ovaries. PID can cause scarring inside the reproductive organs, which can later cause serious complications, including chronic pelvic pain, difficulty becoming pregnant, ectopic (tubal) pregnancy, and other dangerous complications of pregnancy.

Chlamydia is known as the "silent epidemic" as in women, it may not cause any symptoms in 70–80% of cases,[4] and can linger for months or years before being discovered. Signs and symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge, abdominal pain, painful sexual intercourse, fever, painful urination or the urge to urinate more often than usual (urinary urgency).

For sexually active women who are not pregnant, screening is recommended in those under 25 and others at risk of infection.[5] Risk factors include a history of chlamydial or other sexually transmitted infection, new or multiple sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use.[6] Guidelines recommend all women attending for emergency contraceptive are offered Chlamydia testing, with studies showing up to 9% of women aged <25 years had Chlamydia.[7]

Men

In men, those with a chlamydial infection show symptoms of infectious inflammation of the urethra in about 50% of cases.[4] Symptoms that may occur include: a painful or burning sensation when urinating, an unusual discharge from the penis, testicular pain or swelling, or fever. If left untreated, chlamydia in men can spread to the testicles causing epididymitis, which in rare cases can lead to sterility if not treated.[4] Chlamydia is also a potential cause of prostatic inflammation in men, although the exact relevance in prostatitis is difficult to ascertain due to possible contamination from urethritis.[8]

Eye disease

Chlamydia conjunctivitis or trachoma was once the most important cause of blindness worldwide, but its role diminished from 15% of blindness cases by trachoma in 1995 to 3.6% in 2002.[9][10] The infection can be spread from eye to eye by fingers, shared towels or cloths, coughing and sneezing and eye-seeking flies.[11] Newborns can also develop chlamydia eye infection through childbirth (see below). Using the SAFE strategy (acronym for surgery for in-growing or in-turned lashes, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvements), the World Health Organization aims for the global elimination of trachoma by 2020 (GET 2020 initiative).[12][13]

Joints

Chlamydia may also cause reactive arthritis—the triad of arthritis, conjunctivitis and urethral inflammation—especially in young men. About 15,000 men develop reactive arthritis due to chlamydia infection each year in the U.S., and about 5,000 are permanently affected by it. It can occur in both sexes, though is more common in men.

Infants

As many as half of all infants born to mothers with chlamydia will be born with the disease. Chlamydia can affect infants by causing spontaneous abortion; premature birth; conjunctivitis, which may lead to blindness; and pneumonia.[3] Conjunctivitis due to chlamydia typically occurs one week after birth (compared with chemical causes (within hours) or gonorrhea (2–5 days)).

Other conditions

A different serovar of Chlamydia trachomatis is also the cause of lymphogranuloma venereum, an infection of the lymph nodes and lymphatics. It usually presents with genital ulceration and swollen lymph nodes in the groin, but it may also manifest as rectal inflammation, fever or swollen lymph nodes in other regions of the body.[14]

Transmission

Chlamydia can be transmitted during vaginal, anal, or oral sex. Chlamydia can also be passed from an infected mother to her baby during vaginal childbirth.[3]

Pathophysiology

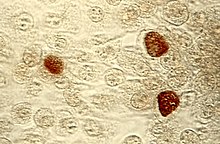

Chlamydiae have the ability to establish long-term associations with host cells. When an infected host cell is starved for various nutrients such as amino acids (for example, tryptophan),[15] iron, or vitamins, this has a negative consequence for Chlamydiae since the organism is dependent on the host cell for these nutrients. Long-term cohort studies indicate that approximately 50% of those infected clear within a year, 80% within two years, and 90% within three years.[16]

The starved chlamydiae enter a persistent growth state wherein they stop cell division and become morphologically aberrant by increasing in size.[17] Persistent organisms remain viable as they are capable of returning to a normal growth state once conditions in the host cell improve.

There is much debate as to whether persistence has in vivo relevance. Many believe that persistent chlamydiae are the cause of chronic chlamydial diseases. Some antibiotics such as β-lactams can also induce a persistent-like growth state, which can contribute to the chronicity of chlamydial diseases.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of genital chlamydial infections evolved rapidly from the 1990s through 2006. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), transcription mediated amplification (TMA), and the DNA strand displacement amplification (SDA) now are the mainstays. NAAT for chlamydia may be performed on swab specimens sampled from the cervix (women) or urethra (men), on self-collected vaginal swabs, or on voided urine.[18] NAAT has been estimated to have a sensitivity of approximately 90% and a specificity of approximately 99%, regardless of sampling from a cervical swab or by urine specimen.[19] In women seeking an STI clinic and a urine test is negative, a subsequent cervical swab has been estimated to be positive in approximately 2% of the time.[19]

At present, the NAATs have regulatory approval only for testing urogenital specimens, although rapidly evolving research indicates that they may give reliable results on rectal specimens.

Because of improved test accuracy, ease of specimen management, convenience in specimen management, and ease of screening sexually active men and women, the NAATs have largely replaced culture, the historic gold standard for chlamydia diagnosis, and the non-amplified probe tests. The latter test is relatively insensitive, successfully detecting only 60–80% of infections in asymptomatic women, and often giving falsely positive results. Culture remains useful in selected circumstances and is currently the only assay approved for testing non-genital specimens.

Screening

For sexually active women who are not pregnant, screening is recommended in those under 25 and others at risk of infection.[5] Risk factors include a history of chlamydial or other sexually transmitted infection, new or multiple sexual partners, and inconsistent condom use.[6] For pregnant women, guidelines vary: screening women with age or other risk factors is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (which recommends screening women under 25) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (which recommends screening women aged 25 or younger). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening all at risk, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend universal screening of pregnant women.[5] The USPSTF acknowledges that in some communities there may be other risk factors for infection, such as ethnicity.[5] Evidence-based recommendations for screening initiation, intervals and termination are currently not possible.[5] For men, the USPSTF concludes evidence is currently insufficient to determine if regular screening of men for chlamydia is beneficial.[6] They recommend regular screening of men who are at increased risk for HIV or syphilis infection.[6]

In the United Kingdom the National Health Service (NHS) aims to:

- Prevent and control chlamydia infection through early detection and treatment of asymptomatic infection;

- Reduce onward transmission to sexual partners;

- Prevent the consequences of untreated infection;

- Test at least 25 percent of the sexually active under 25 population annually.[20]

- Retest after treatment.[21]

Treatment

C. trachomatis infection can be effectively cured with antibiotics once it is detected. Current guidelines recommend azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, or ofloxacin.[22] Agents recommended for pregnant women include erythromycin or amoxicillin.[23]

An option for treating partners of patients (index cases) diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea is patient-delivered partner therapy (PDT or PDPT), which is the clinical practice of treating the sex partners of index cases by providing prescriptions or medications to the patient to take to his/her partner without the health care provider first examining the partner.[24]

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, sexually transmitted chlamydia affects approximately 215 million people (3.1% of the population).[26] It is more common in women (3.8%) than men (2.5%).[26] In that year it resulted in about 1,200 deaths down from 1,500 in 1990.[27]

CDC estimates that there are approximately 2.8 million new cases of chlamydia in the United States each year[28] and that it affects around 2% of young people in that country.[29] Chlamydial infection is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the UK.[30]

Chlamydia causes more than 250,000 cases of epididymitis in the U.S. each year. Chlamydia causes 250,000 to 500,000 cases of PID every year in the United States. Women infected with chlamydia are up to five times more likely to become infected with HIV, if exposed.[3]

References

- ^ "CDC - Trachoma, Hygiene-related Diseases, Healthy Water". Center For Disease Control. December 28, 2009. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (22 August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet (London, England). 386 (9995): 743–800. PMID 26063472.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "STD Facts - Chlamydia". Center For Disease Control. December 16, 2014. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

- ^ a b c NHS Chlamydia page

- ^ a b c d e Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K.; et al. (2008). "USPSTF Recommendations for STI Screening". Am Fam Physician. 77 (6): 819–824.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2007). "Screening for chlamydial infection: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement". Ann Intern Med. 147 (2): 128–34. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00172. PMID 17576996.

- ^ Yeung E, Comben E, McGarry C, Warrington R. (2015). "STI testing in emergency contraceptive consultations". British Journal of General Practice. 65 (631): 63. doi:10.3399/bjgp15X683449. PMID 25624285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wagenlehner FM, Naber KG, Weidner W (2006). "Chlamydial infections and prostatitis in men". BJU Int. 97 (4): 687–90. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06007.x. PMID 16536754.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thylefors B, Négrel AD, Pararajasegaram R, Dadzie KY (1995). "Global data on blindness" (PDF). Bull World Health Organ. 73 (1): 115–21. PMC 2486591. PMID 7704921.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Etya'ale D, Kocur I, Pararajasegaram R, Pokharel GP, Mariotti SP (2004). "Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002" (PDF). Bull World Health Organ. 82 (11): 844–851. doi:10.1590/S0042-96862004001100009. PMC 2623053. PMID 15640920.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mabey DC, Solomon AW, Foster A (2003). "Trachoma". Lancet. 362 (9379): 223–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13914-1. PMID 12885486.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organisation. Trachoma. Accessed March 17, 2008.

- ^ Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, Reacher M, Brayne C, Baba S, Solomon AW, Zingeser J, Emerson PM (2006). "Effect of 3 years of SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change) strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: a cross-sectional study". Lancet. 368 (9535): 589–95. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69202-7. PMID 16905023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams D, Churchill D (2006). "Ulcerative proctitis in men who have sex with men: an emerging outbreak". BMJ. 332 (7533): 99–100. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7533.99. PMC 1326936. PMID 16410585.

- ^ Leonhardt RM, Lee SJ, Kavathas PB, Cresswell P (2007). "Severe Tryptophan Starvation Blocks Onset of Conventional Persistence and Reduces Reactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis". Infect. Immun. 75 (11): 5105–17. doi:10.1128/IAI.00668-07. PMC 2168275. PMID 17724071.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fairley CK, Gurrin L, Walker J, Hocking JS (2007). ""Doctor, How Long Has My Chlamydia Been There?" Answer:"... Years"". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 34 (9): 727–8. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31812dfb6e. PMID 17717486.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mpiga P, Ravaoarinoro M (2006). "Chlamydia trachomatis persistence: an update". Microbiol. Res. 161 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2005.04.004. PMID 16338585.

- ^ Gaydos CA; et al. (2004). "Comparison of three nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in urine specimens". J Clin Microbio. 42 (7): 3041–3045. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.7.3041-3045.2004.

- ^ a b Haugland S, Thune T, Fosse B, Wentzel-Larsen T, Hjelmevoll SO, Myrmel H (2010). "Comparing urine samples and cervical swabs for Chlamydia testing in a female population by means of Strand Displacement Assay (SDA)". BMC Womens Health. 10 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-10-9. PMC 2861009. PMID 20338058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "National Chlamydia Screening Programme Data tables". Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- ^ Desai, Monica; Woodhall, Sarah C; Nardone, Anthony; Burns, Fiona; Mercey, Danielle; Gilson, Richard (2015). "Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review". Sexually Transmitted Infections: sextrans-2014-051930. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051930. ISSN 1368-4973Strategies for improved follow up care include the use of text messages and emails from those who provided treatment.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ al.], David N. Gilbert ... [et. The Sanford guide to antimicrobial therapy 2011. Sperryville, VA: Antimicrobial Therapy, Inc. p. 20. ISBN 1-930808-65-8.

- ^ "Diagnosis and Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis Infection - April 15, 2006 - American Family Physician". Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ Expedited Partner Therapy in the Management of Sexually Transmitted Diseases (2 February 2006) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2004. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S; et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY; et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "STD Trends in the United States: 2010 National Data for Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, and Syphilis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 22 November 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ Torrone, E; Papp, J; Weinstock, H (Sep 26, 2014). "Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infection Among Persons Aged 14-39 Years - United States, 2007-2012". MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 63 (38): 834–838. PMID 25254560.

- ^ "Chlamydia". UK Health Protection Agency. Retrieved 31 August 2012.