Colitis-X

Colitis X, equine colitis X or peracute toxemic colitis is a catchall term for various fatal forms of acute or peracute colitis found in horses, but particularly a fulminant colitis where clinical signs include sudden onset of severe diarrhea, abdominal pain, shock, and dehydration. Death is common, with 90% to 100% mortality, usually in less than 24 hours. The causative factor may be Clostridium difficile, but it also may be caused by other intestinal pathogens. Horses under stress appear to be more susceptible to developing colitis X, and like the condition pseudomembranous colitis in humans, there also is an association with prior antibiotic use. Immediate and aggressive treatment can sometimes save the horse, but even in such cases, 75% mortality is considered a best-case scenario.

Clinical signs

Colitis-X is a term used for colitis cases in which no definitive diagnosis can be made and the horse dies.[1] Clinical signs include sudden, watery diarrhea that is usually accompanied by symptoms of hypovolemic shock and usually leads to death in 3 to 48 hours, usually in less than 24 hours. Other clinical signs include tachycardia, tachypnea, and a weak pulse. Marked depression is present. An explosive diarrhea develops, resulting in extreme dehydration. Hypovolemic and endotoxic shock are manifest by increased capillary refill time, congested or cyanotic (purplish) mucous membranes, and cold extremities. While there may initially be a fever, temperature usually returns to normal.[1][2]

Clinical signs are similar to those of other diarrheal diseases, including toxemia caused by Clostridium, Potomac horse fever, experimental endotoxic shock, and anaphylaxis.[1]

Causes

To date, the precise causative factor has not been verified, and the disease has been attributed by various sources to viruses, parasites, bacteria, use of antibiotics and sulfonamides, and heavy metal poisoning.[1][2][3] Other possible causes include peracute salmonellosis, clostridial enterocolitis, and endotoxemia.[1] Clostridium difficile toxins isolated in the horse have a genotype like the current human "epidemic strain", which is associated with human C. difficile-associated disease of greater than historical severity.[4] C. difficile can cause pseudomembranous colitis in humans,[5] and in hospitalized patients who develop it, fulminant C. difficile colitis is a significant and increasing cause of death.[6]

Horses under stress appear to be more susceptible to developing colitis X.[2] Disease onset is often closely associated with surgery or transport.[1] Excess protein and lack of cellulose content in the diet (a diet heavy on grain and lacking adequate hay or similar roughage) is thought to be the trigger for the multiplication of clostridial organisms.[3] A similar condition may be seen after administration of tetracycline or lincomycin to horses.[1] These factors may be one reason the condition often develops in race horses, having been responsible for the deaths of the Thoroughbred filly Landaluce,[7][8] the Quarter Horse stallion Lightning Bar,[9] and is one theory for the sudden death of Kentucky Derby winner Swale.[7]

The link to stress suggests the condition may be brought on by changes in the microflora of the cecum and colon that lower the number of anaerobic bacteria, increase the number of Gram-negative enteric bacteria, and decrease anaerobic fermentation of soluble carbohydrates, resulting in damage to the cecal and colonic mucosa and allowing increased absorption of endotoxins from the lumen of the gut.[10]

The causative agent may be Clostridium perfringens, type A, but the bacteria are recoverable only in the preliminary stages of the disease.[3]

The suspect toxin could also be a form of Clostridium difficile. In a 2009 study at the University of Arizona, C. difficile toxins A and B were detected, large numbers of C. difficile were isolated, and genetic characterization revealed them to be North American pulsed-field gel electrophoresis type 1, polymerase chain reaction ribotype 027, and toxinotype III. Genes for the binary toxin were present, and toxin negative-regulator tcdC contained an 18-bp deletion. The individual animal studied in this case was diagnosed as having peracute typhlocolitis, with lesions and history typical of those attributed to colitis X.[4]

Use of antibiotics may also be associated with some forms of colitis-X.[11] In humans, C. difficile is the most serious cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea, often a result of eradication of the normal gut flora by antibiotics.[12] In one equine study, colitis was induced after pretreatment with clindamycin and lincomycin, followed by intestinal content from horses which had died from naturally occurring idiopathic colitis.[11] (A classic adverse effect of clindamycin in humans is C. difficile-associated diarrhea.[13]) In the experiment, the treated horses died.[11] After necropsy, Clostridium cadaveris was present, and is proposed as another possible causative agent in some cases of fatal colitis.[11]

Diagnosis

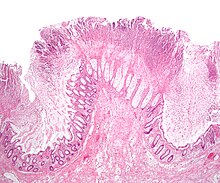

At necropsy, edema and hemorrhage in the wall of the large colon and cecum are pronounced, and the intestinal contents are fluid and often blood-stained.[1] Macroscopic and microscopic findings include signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation, necrosis of colonic mucosa and presence of large numbers of bacteria in the devitalized parts of the intestine.[3] Typically, the PCV is >65% even shortly after the onset of clinical signs. The leukogram ranges from normal to neutropenia with a degenerative left shift. Metabolic acidosis and electrolyte disorders are also present.[1] There is leucopenia, initially characterized by neutropenia, which might evolve in neutrophilia. Moreover, haemoconcentration is noted with an increase in the packed cell volume; total proteins are initially increased, but changes into a lower than normal value. The most significant laboratory finding in colitis X is the increase of total cortisol concentration in blood plasma. Histopathologically, the mucosa of the large colon is hemorrhagic, necrotic and covered with fibrohemorrhagic exudate, while the submucosa, the muscular tunic and the local lymphonodes are edematous.[2]

Treatment

Treatment for colitis-X usually does not save the horse. The prognosis is average to poor, and mortality is 90% to 100%.[1][2] However, treatments are available, and one famous horse that survived colitis-X was U.S. Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew, that survived colitis-X in 1978 and went on to race as a four-year-old.[7][8][14] Large amounts of intravenous fluids are needed to counter the severe dehydration, and electrolyte replacement is often necessary. Flunixin meglumine (Banamine) may help block the effects of toxemia.[1] Mortality rate has been theorized to fall to 75% if treatment is prompt and aggressive, including administration of not only fluids and electrolytes, but also blood plasma, anti-inflammatory and analgesic drugs, and antibiotics. Preventing dehydration is extremely important. Nutrition is also important. Either parenteral or normal feeding can be used to support the stressed metabolism of the sick horse. Finally, the use of probiotics is considered beneficial in the restoration of the normal intestinal flora. The probiotics most often used for this purpose contain Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium.[2]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Colitis-X". Merck Veterinary Manual. Merck & Co., Inc.W. 2008. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ a b c d e f

Diakakis, N. (January–March 2008). "Equine colitis X". Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society (Volume 59, Number 1). Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society: 23–28(6).

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ a b c d Schiefer HB (May 1981). "Equine colitis "X", still an enigma?". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. La Revue Vétérinaire Canadienne. 22 (5): 162–5. PMC 1790040. PMID 6265055.

- ^ a b Songer JG, Trinh HT, Dial SM, Brazier JS, Glock RD (May 2009). "Equine colitis X associated with infection by Clostridium difficile NAP1/027". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 21 (3): 377–80. doi:10.1177/104063870902100314. PMID 19407094.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wells CL, Wilkins TD (1996). Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea, Pseudomembranous Colitis, and Clostridium difficile in: Baron's Medical Microbiology (Baron S et al., eds.) (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ^ Dallal RM, Harbrecht BG, Boujoukas AJ; et al. (March 2002). "Fulminant Clostridium difficile: an underappreciated and increasing cause of death and complications". Annals of Surgery. 235 (3): 363–72. doi:10.1097/00000658-200203000-00008. PMC 1422442. PMID 11882758.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c DeVito, Carlo (2002). D. Wayne: The High-Rolling and Fast Times of America's Premier Horse Trainer. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-0-07-138737-8.

- ^ a b Leggett, William (June 25, 1984). "Suddenly A Young Champion Is Gone". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- ^

Simmons, Diane (1994). "Lightning Bar". Legends 2: Outstanding Quarter Horse Stallions and Mares. Colorado Springs, CO: Western Horseman. p. 149. ISBN 0-911647-30-9.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Srivastava, K. "Colitis X (Peracute Toxemic Colitis)". Biomedical Research and Graduate Studies Resources, Large Animal Laboratory Animal Medicine. Tuskegee University. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- ^ a b c d Prescott JF, Staempfli HR, Barker IK, Bettoni R, Delaney K (November 1988). "A method for reproducing fatal idiopathic colitis (colitis X) in ponies and isolation of a clostridium as a possible agent". Equine Veterinary Journal. 20 (6): 417–20. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1988.tb01563.x. PMID 3215166.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Curry J (2007-07-20). "Pseudomembranous Colitis". eMedicine. WebMD. Retrieved 2008-11-17.

- ^ Thomas C, Stevenson M, Riley TV (June 2003). "Antibiotics and hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a systematic review". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 51 (6): 1339–50. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg254. PMID 12746372.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sparkman, John P. (2010). "A veritable slew of sons". The Thoroughbred Times. Retrieved 2010-01-13.