Constitution of Tasmania

| Tasmanian Constitution | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Original title | Constitution Act 1934 (Tas), s. 1 |

| Jurisdiction | Tasmania |

| Ratified | 18 October 1934 |

| Date effective | 1 January 1935 |

| System | State Government |

| Government structure | |

| Branches | |

| Chambers | |

| Executive | See Tasmanian Government |

| Judiciary | See Judiciary of Australia |

| History | |

| Amendments | 71 |

| Last amended | Expansion of House of Assembly Act 2022 |

| Supersedes | Constitution Act 1855 (Tas) |

The Constitution of Tasmania, also known as the Tasmanian Constitution, sets out the rules, customs and laws that provide for the structure of the Government of the Australian State of Tasmania. Like all state constitutions it consists of both unwritten and written elements which include:

- the Constitution Act 1934 (Tas)

- the Letters Patent of 2005 (which constitutes and outlines the roles and responsibilities of the Governor of Tasmania

- other important constitutional statutes like the Supreme Court Act 1959 or the Electoral Act 2004

- Constitutional conventions

- Common law

- any remaining applicable British legislation of a constitutional nature, like the Bill of Rights 1689

- the Federal Constitution

- the Australia Acts[1]

The Constitution Act 1934 has been described as the worst of state constitutions by constitutional academic George Williams, most notably for its omission of key institutions such as the Supreme Court and the Governor and lack of effective entrenchments.[1]

History

[edit]Colonisation

[edit]

Tasmania was first colonised by Europeans as 'Van Diemen's Land' in 1804,[1] named after Anthony van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies, who had sent Abel Tasman to explore the island in 1642.[2] Van Diemen's land was originally a part of the Colony of New South Wales and was governed by a Lieutenant Governor under the command of the Governor of New South Wales. The island was further divided into two administrative regions along the 42nd parallel, with the Lieutenant Governor governing the south at Hobart and a commandant in the north at Port Dalrymple (now George Town). The two regions were not joined under one Lieutenant Governor until 1812.[3]

In 1823 the British Parliament passed the New South Wales Act 1823 (UK), which separated Van Diemen's land from New South Wales as its own colony.[4] The act also limited the Lieutenant Governor's autocratic powers by creating a Legislative Council to advise him and be responsible for creating new laws. The Council would consist of six members chosen by him, and would be expanded in 1828 to 15 members with the Lieutenant Governor as the presiding officer.[5]

Australian Constitutions Act 1850 (UK)

[edit]The Legislative Council was expanded to 24 members in 1851 after the British Parliament passed the Australian Constitutions Act 1850 (UK). 16 members would be elected by the white men of the colony who met the property ownership qualifications, while 8 would remain appointed. It also authorised the Council to write a Constitution for the colony that incorporated the concepts of responsible and representative government.[1]

Constitution Act 1855 (Tas)

[edit]The Legislative Council passed a constitution in 1854, which received Royal Assent from Queen Victoria in 1855. This new constitution would create a bicameral Parliament, which retained the Legislative Council, with 15 members elected on a rotating 3 year basis. The lower chamber would be called the House of Assembly which would have 30 members elected every 5 years. Both chambers would retain property or educational qualifications in order to vote. The position of Lieutenant Governor was also upgraded to that of a Governor alongside other Australian colonies of equal status.[6]

In 1856 following a successful petition by the Legislative Council to the Queen, the Colony was renamed from Van Diemen's Land to Tasmania.[1] Later that year, William Champ was elected as Tasmania's first Premier, following the Colony's first elections under the 1855 Constitution.[7]

From 1856 until 1899, property qualifications for voters were slowly reduced until they were abolished in 1900 for the House of Assembly alongside education qualifications.[8] Tasmania was the last colony in Australia to introduce universal white male franchise, though Tasmania did not explicitly prohibit Aboriginal men from voting.[9] In 1903, Tasmania amended its constitution to introduce universal female suffrage, though women did not gain the right to stand for the State Parliament until 1921.[8]

Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 (UK)

[edit]In response to Justice Boothby declaring several South Australian laws void for being repugnant to the law of the United Kingdom, the British Parliament passed the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 to validate the laws passed by all of its colonial legislatures.[10] What this meant is that the Tasmanian Parliament could pass laws that were inconsistent with most British laws. The exception to this were laws that explicitly applied to the colonies.[11]

Effect of the Federal Constitution

[edit]In the lead up to federation, Tasmania held its first statewide referendum on the question of union with the other colonies, alongside simultaneous referendums in New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria in 1898. While 81% of eligible Tasmanians voted yes, only 71,595 (51%) of those eligible in New South Walesdid.[12] As the enabling legislation in New South Wales required at least 80,000 of those eligible in that state to approve, the Constitution bill had to be amended to make it more favourable to New South Wales voters. The newly amended bill was resubmitted to the colonies for approval in 1899-1900 (this time including Queensland and Western Australia).[13] This time Tasmania approved the bill with an even greater majority of 94%.[12]

When the Federal Constitution was enacted on New Year's Day 1901, the Colony of Tasmania became a State of the Commonwealth of Australia. Sections 106, 107 and 108 of the Federal Constitution preserved the State's laws, the Tasmanian Parliament's broad plenary lawmaking powers and its Colonial Constitution became a State Constitution. Though this is qualified by section 109 which states that when the law of the State and the law of the Commonwealth are inconsistent, the Commonwealth law shall prevail to the extent of the inconsistency.[11]

The Federal Constitution also withdraws the power of Tasmania to:

- implement customs, excises and bounties. (section 90)

- interfere with interstate trade, commerce and intercourse (section 92)

- tax property of the Commonwealth (section 114)

- coin money (section 115)

- raise military forces (section 114)

- nor discriminate against residents of other states (section 117)

among other minor and implied restrictions.[11]

Constitution Act 1934 (Tas)

[edit]

By the 1930s, the Tasmanian Parliament had created a number of different statutes on constitutional topics that were located outside the Constitution Act 1855. This included electoral qualifications, membership of the houses, rules on appropriations, public salaries and appointments, the status and demise of the crown, and the conduct of elections. This led to growing calls within the Tasmanian Parliament to consolidate some of these elements within a new constitution, which the McPhee Government did in 1934. Aside from consolidating some of Tasmania's constitutional statutes, very few new features were included. An example of this is section 46 which proclaims religious freedom and equality, and prevents ant religious test for holding public office, however this does not prevent the Parliament of Tasmania from overriding this provision.[1]

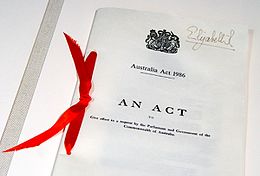

Australia Acts

[edit]

The Commonwealth had freed itself from colonial restraints and secured its independence from the United Kingdom by adopting the Statute of Westminster 1931 (UK) through passing the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 (Cth). This statute ended any power of the British Parliament to make laws for Australia at the federal level without their consent, prevented federal laws (those passed after 1939) from being declared void due to inconsistency with British laws and gave the Federal Parliament to repeal or amend any British law that applied to Australia at the federal level.[11] However due to an oversight, this did not apply to Australian States. Meaning that until 1986, Tasmania remained a dependency of the British Crown while the Federal layer was effectively entirely independent from the United Kingdom. This odd situation meant that the British Government was responsible for advising the Monarch who would be the Governor of Tasmania and when certain proposed laws had to bypass the Governor to be given Royal Assent by the Monarch directly, the British Government could advise the Monarch to refuse assent to Tasmanian laws.[14]

The reason this arrangement persisted for so long was that the States continued to claim that they were co-sovereign and coequal to the Commonwealth Government. This claim would continue to be denied by successive Commonwealth Governments who viewed themselves as the sole possessors of Australian sovereignty. Thus any change to the constitutional arrangements of the states to secure their independence from the United Kingdom could be an opportunity for the Commonwealth to assert its dominance over the states. Meaning that the States had greater trust in the United Kingdom to be responsible for its affairs than the Commonwealth Government.[14]

The Commonwealth and the States finally agreed to a deal that would not comprise the constitutional integrity of the states.[14] Each state passed a statute that requested both the British and Commonwealth Parliaments to legislate in a way that removed colonial era links between their state and the UK. The Tasmanian Parliament passed the Australia Acts (Request) Act 1985 (Tas), which was followed by the Australia Act 1986 (Cth) and Australia Act 1986 (UK).[11][15] and Commonwealth statutes were almost identical and made a number of changes for Tasmania:

- Terminated the power of the British Parliament over Tasmania forever (as well as all other parts of Australia) (section 1)

- Allowed the Tasmanian Parliament to repeal or amend British laws that applied specifically to Tasmania (section 3)

- Prevented Tasmanian laws passed after 1986 from being struck down on the basis that they were repugnant to British laws (section 3)

- Allowed the Tasmanian Parliament to pass laws that had extraterritorial application (section 2)[11]

- Prevented the Monarch from suspending or disallowing laws given assent from the Tasmanian Governor (section 8)

- Invalidated any requirements that laws on certain topics had to be reserved for the Monarch's personal assent (section 9)

- Required that the Monarch act on the advice of the Premier when exercising their powers (not the British Government) (section 7)

- Requiring that only the Governor can exercise the Monarch's power when the Monarch is not personally present in Tasmania (apart from the Governor's appointment itself) (section 7)[14]

Document Structure and Text

[edit]Preamble

[edit]The preamble gives a short explanation of Tasmania's constitutional history, as well as an acknowledgement of Tasmanian Aboriginals as the island's indigenous people.

Part I: Preliminary

[edit]This part deals with the short title of the Constitution Act and also provides definitions for key terms used later on.

Part II: The Crown

[edit]

This part deals with the Crown in right of Tasmania. The term 'the Crown' can mean different things depending on the context, but this context it means the executive government of Tasmania.[16] Sections 4 to 7 deal with the continuity of government in the event of the death of the Monarch.

Section 8 deals with the appointment of an Administrator or Deputy Lieutenant Governor to act in the place of the Lieutenant Governor or Governor. This means that the Government of Tasmania can continue to be administered in the absence, death or incapacity of the Governor or Lieutenant Governor. Section 8(1) recognises the continuing legal force of the Letters Patent, which constitutes the office of Governor and Lieutenant Governor, as well as the Executive Council

Sections 8A to 8I deal with the appointment of ministers, the Attorney General (who is also a minister) and the Cabinet Secretary (who is not a minister).

Part III: Parliament

[edit]Division 1: Both Houses

[edit]This division deals with issues relating to both houses, specifically dealing with:

- when Parliament shall sit (sections 11, 12 and 13)

- when the Governor may dissolve the Parliament and issue writs for fresh elections (section 12)

- the qualifications for candidates to run for Parliament (section 14)

- how someone may resign their seat in Parliament (section 15)

- the creation of standing orders by either house (section 17)

Division 2: The Council

[edit]This division creates the Legislative Council as the upper chamber. Section 18 states that it shall have 15 members, each elected from a single member electorates called Council divisions. This makes it the only Parliament in Australia that uses single member electorates for its upper chamber. Section 19 states the members of the council shall serve for a term of 6 years.

Sections 20 and 21 deal with the quorum required to proceed with the business of the Council (which is 7) and the election of the President, who presides over the Council.

Division 3: The Assembly

[edit]This division creates the House of Assembly as the lower chamber. According to constitutional convention, this chamber is where a party or coalition must form a majority in order to control the executive government. By convention, the Premier is usually a member of the Assembly, but historically this has not always been the case.[17]

Sections 22 and 23 detail that the House of Assembly comprises 35 members elected for a four year term. For the purposes of electing the Assembly, the State is divided into 5 multi-member electorates, which each return 7 members each. It is the only State Parliament in Australia that has multi-member electorates for its lower chamber called Assembly divisions. The Australian Capital Territory Legislative Assembly also uses multi member electorates but it is a territory, unicameral and is not technically labelled a Parliament. The boundaries of the five assembly districts are the same as Tasmania's five federal electorates for the House of Representatives in the Commonwealth Parliament.[18]

Sections 24 and 25 deal with the quorum required to conduct the business of the Assembly (which is 14) and the election of the Speaker to preside over the Assembly.

Division 4: Qualifications of electors

[edit]This division provides some of the qualifications in order to vote for Parliament, although it also recognises there may be further requirements in the Electoral Act 2004. The qualifications include being at least 18 and an Australian citizen. It also provides that someone may only vote for the Council and Assembly division they live in.

Division 5: Disqualifications/Vacation of office/Penalty

[edit]This division primarily deals with circumstances in which someone shall be disqualified from being a member of Parliament. The following conditions mean that a person shall be incapable holding of office as a Parliamentarian if they:

- are a member of the Commonwealth Parliament, or a Commonwealth Minister (section 31)

- hold some other government office (other than that of a Tasmanian Minister or Cabinet Secretary) (section 32)

- are a Tasmanian Supreme Court Judge (section 32)

- have a contract with the Government in certain circumstances (section 33)

- fail to attend an entire session of Parliament without being excused by either house (section 34)

- take any oath, declaration or act of allegiance to a foreign power (section 34)

- knowingly become a foreign citizen (section 34)

- are bankrupt (section 34)

- commit treason, or are sentenced to more than one year in prison (unless pardoned) (section 34)

- become of unsound mind (section 34)

Section 30 also details the oath required to become a Parliamentarian.

Part IV: Money Bills/Power of Houses

[edit]This part provides for how money bills shall be enacted by the Parliament. Money bills are proposed laws that allow for the expenditure of money and the imposition of taxes. Sections 37 and 38 provide that money bills shall only be initiated by the Assembly on the recommendation of the Governor. This power of the Governor is exercised on the advice of Ministers, so effectively this means that Money Bills can only be implemented with the consent of the executive government.

Sections 39 and 40 provide that bills that spend money shall only contain provisions for that purpose. Section 41 provides that bills adjusting land or income taxes shall only deal with land or income taxes. Section 42 limits the powers of the Council to amend Money bills, however it can suggest amendments to the Assembly (which the Assembly may reject).

Part IVA: Local Government

[edit]This part provides for a system of elected councils to act as the local governments of Tasmania.

Part V: General Provisions

[edit]- Section 46 provides for religious freedom and separation of church and state, however this does not prevent the Parliament of Tasmania from overriding this provision.[1]

- Section 47 contains transitional provisions from when the House of Assembly was expanded from 25 to 35 members in 2022.

Schedules

[edit]- Schedule 1 provides a list of statutes that were repealed by the Constitution Act 1934.

- Schedules 2-3 have been repealed.

- Schedule 4 provides the names and locations of the Assembly districts.

Amendment

[edit]Almost the entire Constitution Act is unentrenched, meaning the Tasmanian Parliament may amend it with a simple majority of both houses. The sole exception is section 41A which prevents the Tasmanian Parliament from amending section 23, to extend or reduce the term of Parliament without a 2/3rds majority in either house. However this section is not doubly entrenched in order to be effective, thus the Parliament could repeal section 41A with a simple majority to get around the 2/3rds majority requirement in order to amend section 23.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gogarty, Brendan (2016). "The Worst of the State Constitutions: Why Aboriginal Constitutional Recognition Must Be Framed Against a Wider Reform of Tasmania's Constitution Act". University of Tasmania Law Review. 35 (1): 1–23. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Haynes, Ross. "Van Diemens Land". The Companion to Tasmanian History. University of Tasmania. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Colonel Collins' Commission 14 January 1803 (NSW)". Documenting Democracy. Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "New South Wales Act 1823 (UK)". Documenting Democracy. Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Stait, Bryan. "Legislative Council". The Companion to Tasmanian History. University of Tasmania. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Constitution Act 1855 (Tas)". Documenting Democracy. Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Barry, John. William Thomas Napier Champ (1808–1892). Australian National University. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b Newman, Terry. "Franchise". The Companion to Tasmanian History. University of Tasmania. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Curthoys, Ann; Mitchell, Jessie (2013). "The advent of self-government". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. pp. 164–65.

- ^ Williams, John (2006). Winterton, George (ed.). State Constitutional Landmarks. Sydney: Federation Press. pp. 21–50. ISBN 9781862876071.

- ^ a b c d e f Joseph, Sarah; Castan, Melissa (2019). Federal Constitutional Law: A Contemporary View. Pyrmont, Sydney: Thomson Reuters. pp. 18–20, 27, 30–32. ISBN 9780455241449.

- ^ a b "The Referendums 1898–1900". Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "The Federation of Australia". Parliamentary Education Office. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d Twomey, Anne (2006). The Chameleon Crown: The Queen and her Australian Governors. Annandale, Sydney: Federation Press. pp. v–xi, 81–94, 258–271. ISBN 9781862876293.

- ^ Australia Act (Request) Act 1985 (Tas)

- ^ Saunders, Cheryl (2015). "The Concept of the Crown: International Relations and the British Commonwealth" (PDF). Melbourne University Law Review. 38: 873–896. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "Premier and Leader of Opposition". Parliament of Tasmania. 13 June 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Stait, Bryan. "House of Assembly". The Companion to Tasmanian History. University of Tasmania. Retrieved 23 January 2024.