Federation of Australia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

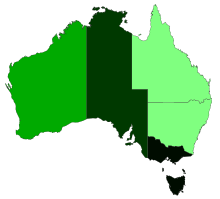

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Western Australia agreed to unite and form the Commonwealth of Australia, establishing a system of federalism in Australia. The colonies of Fiji and New Zealand were originally part of this process, but they decided not to join the federation.[1] Following federation, the six colonies that united to form the Commonwealth of Australia as states kept the systems of government (and the bicameral legislatures) that they had developed as separate colonies, but they also agreed to have a federal government that was responsible for matters concerning the whole nation. When the Constitution of Australia came into force, on 1 January 1901, the colonies collectively became states of the Commonwealth of Australia.

The efforts to bring about federation in the mid-19th century were dogged by the lack of popular support for the movement. A number of conventions were held during the 1890s to develop a constitution for the Commonwealth. Sir Henry Parkes, Premier of the Colony of New South Wales, was instrumental in this process. Sir Edmund Barton, second only to Parkes in the length of his commitment to the federation cause, was the caretaker Prime Minister of Australia at the inaugural national election in March 1901. The election returned Barton as prime minister, though without a majority.

The main economic manifestation of federation was an Australian customs and fiscal union.[2] Although the customs union entailed a high external tariff on imports from outside of Australia, there was the elimination of tariffs on interstate Australian trade, and the net effect of federation on welfare was positive, insofar as trade policy was concerned.[3]

This period has lent its name to an architectural style prevalent in Australia at that time, known as Federation architecture, or Federation style.

Early calls for federation[edit]

As early as 1842, an anonymous article in the South Australian Magazine called for a "Union of the Australasian Colonies into a Governor-Generalship".[4]

In September 1846, the NSW Colonial Secretary Sir Edward Deas Thomson suggested federation in the New South Wales Legislative Council. The Governor of New South Wales, Sir Charles Fitzroy, then wrote to the United Kingdom's Colonial Office suggesting a "superior functionary" with power to review the legislation of all the colonies. In 1853, FitzRoy was appointed as Governor of Van Diemen's Land, South Australia and Victoria – a pre-federation Governor-General of Australia, with wide-ranging powers to intervene in inter-colonial disputes. This title was also extended to his immediate successor, William Denison.[5][6][7]

In 1847 the Secretary of State for the Colonies Earl Grey drew up a plan for a "General Assembly" of the colonies. The idea was quietly dropped.[8] However, it prompted the statesman William Wentworth to propose in the following year the establishment of "a Congress from the various Colonial Legislatures" to legislate on "inter-colonial questions".[9][10]

On 28 July 1853, a select committee formed by Wentworth to draft a new constitution for New South Wales proposed a General Assembly of the Australian Colonies. This assembly was proposed to legislate on intercolonial matters, including tariffs, railways, lighthouses, penal settlements, gold and the mail. This was the first outline of the future Australian Commonwealth to be presented in an official colonial legislative report.[9]

On 19 August 1857, Deas Thomson moved for a NSW Parliamentary Select Committee on the question of Australian federation.[11] The committee reported in favour of a federal assembly being established, but the government changed in the meantime, and the question was shelved.

Also in 1857, in England, William Wentworth founded the "General Association for the Australian Colonies", whose object was to obtain a federal assembly for the whole of Australia.[12] While in London, Wentworth produced a draft Bill proposing a confederation of the Australian colonies, with each colony given equal representation in an intercolonial assembly, a proposal subsequently endorsed by his association. He further proposed a 'permissive Act' be passed by Parliament allowing the colonies of Australia or any subset of them which was not a penal settlement to federate at will. Wentworth, hoping to garner as broad support as possible, proposed a loose association of the colonies, which was criticised by Robert Lowe. The Secretary of State subsequently opted not to introduce the Bill stating it would probably lead to "dissension and discontent," distributing it nonetheless to the colonies for their responses. While there was in-principle support for a union of the colonies, the matter was ultimately deferred while NSW Premier Charles Cowper and Henry Parkes preferred to focus on liberalising Wentworth's squatter-friendly constitution.[9]

Federal Council of Australasia[edit]

A serious movement for Federation of the colonies arose in the late 1880s, a time when there was increasing nationalism amongst Australians, the great majority of whom were native-born. The idea of being "Australian" began to be celebrated in songs and poems. This was fostered by improvements in transport and communications, such as the establishment of a telegraph system between the colonies in 1872. The Australian colonies were also influenced by other federations that had emerged around the world, particularly the United States and Canada.

Sir Henry Parkes, then Colonial Secretary of New South Wales, first proposed a Federal Council body in 1867. After it was rejected by the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Duke of Buckingham, Parkes brought up the issue again in 1880, this time as the Premier of New South Wales. At the conference, representatives from Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia considered a number of issues including federation, communication, Chinese immigration, vine diseases and uniform tariff rates. The Federation had the potential to ensure that throughout the continent, trade and interstate commerce would be unaffected by protectionism and measurement and transport would be standardised.

The final (and successful) push for a Federal Council came at an Intercolonial Convention in Sydney in November and December 1883. The trigger was the British rejection of Queensland's unilateral annexation of New Guinea and the British Government wish to see a federalised Australasia. The convention was called to debate the strategies needed to counter the activities of the German and French in New Guinea and in New Hebrides. Sir Samuel Griffith, the Premier of Queensland, drafted a bill to constitute the Federal Council. The conference successfully petitioned the Imperial Parliament to enact the bill as the Federal Council of Australasia Act 1885.[13]

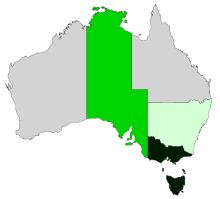

As a result, a Federal Council of Australasia was formed, to represent the affairs of the colonies in their relations with the South Pacific islands. New South Wales and New Zealand did not join. The self-governing colonies of Queensland, Tasmania and Victoria, as well as the Crown Colonies of Western Australia and Fiji, became involved. South Australia was briefly a member between 1888 and 1890. The Federal Council had powers to legislate directly upon certain matters, and did so to effect the mutual recognition of naturalisations by colonies, to regulate labour standards in the employment of Pacific Island labour in fisheries, and to enable a legal suit to be "served" outside the colony in which it was issued, "a power valuable in matters ranging from absconding debtors to divorce proceedings".[14] But the Council did not have a permanent secretariat, executive powers, or any revenue of its own. Furthermore, the absence of the powerful colony of New South Wales weakened its representative value.

Nevertheless, it was the first major form of inter-colonial co-operation. It provided an opportunity for Federalists from around the country to meet and exchange ideas. The means by which the Council was established endorsed the continuing role that the Imperial Parliament would have in the development of Australia's constitutional structure. In terms of the Federal Council of Australia Act, the Australian drafters established a number of powers dealing with their "common interest" which would later be replicated in the Australian Constitution, especially section 51.

Early opposition[edit]

The individual colonies, Victoria excepted, were somewhat wary of Federation. Politicians, particularly those from the smaller colonies, disliked the very idea of delegating power to a national government; they feared that any such government would inevitably be dominated by the more populous New South Wales and Victoria. Queensland, for its part, worried that the advent of race-based national legislation would restrict the importing of kanaka labourers, thereby jeopardising its sugar cane industry.

These were not the only concerns of those resistant to federation. Smaller colonies also worried about the abolition of tariffs, which would deprive them of a large proportion of their revenue, and leave their commerce at the mercy of the larger states. New South Wales, traditionally free-trade in its outlook, wanted to be satisfied that the federation's tariff policy would not be protectionist. Victorian Premier James Service described fiscal union as "the lion in the way" of federation.

A further fundamental issue was how to distribute the excess customs duties from the central government to the states. For the larger colonies, there was the possibility (which never became an actuality) that they could be required to subsidise the struggling economies of Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia.

Even without the concerns, there was debate about the form of government that a federation would take. Experience of other federations was less than inspiring. In particular, the United States had experienced the traumatic Civil War.

The nascent Australian labour movement was less than wholly committed in its support for federation. On the one hand, nationalist sentiment was strong within the labour movement and there was much support for the idea of White Australia. On the other hand, labour representatives feared that federation would distract attention from the need for social and industrial reform, and further entrench the power of the conservative forces. The federal conventions included no representatives of organised labour. In fact, the proposed federal constitution was criticised by labour representatives as being too conservative. These representatives wanted to see a federal government with more power to legislate on issues such as wages and prices. They also regarded the proposed senate as much too powerful, with the capacity to block attempts at social and political reform, much as the colonial upper houses were quite openly doing at that time.

Religious factors played a small but not trivial part in disputes over whether federation was desirable or even possible. As a general rule, pro-federation leaders were Protestants, while Catholics' enthusiasm for federation was much weaker, not least because Parkes had been militantly anti-Catholic for decades (and because the labour movement was disproportionately Catholic in its membership).[15] For all that, many Irish could feel an attractive affinity between the cause of Home Rule in Ireland – effectively federalizing the United Kingdom – and the federation of the Australian colonies.[16] Federationists such as Edmund Barton, with the full support of his righthand man Richard O'Connor, were careful to maintain good relations with Irish opinion.

Early constitutional conventions[edit]

In the early 1890s, two meetings established the need for federation and set the framework for this to occur. An informal meeting attended by official representatives from the Australasian colonies was held in 1890. This led to the first National Australasian Convention, meeting in Sydney in 1891. New Zealand was represented at both the conference and the Convention, although its delegates indicated that it would be unlikely to join the Federation at its foundation, but it would probably be interested in doing so at a later date.

Australasian Federal Conference of 1890[edit]

The Australasian Federal Conference of 1890 met at the instigation of Parkes. Accounts of its origin commonly commence with Lord Carrington, the Governor of New South Wales, goading the ageing Parkes at a luncheon on 15 June 1889. Parkes reportedly boasted that he "could confederate these colonies in twelve months". Carrington retorted, "Then why don't you do it? It would be a glorious finish to your life."[17] Parkes the next day wrote to the Premier of Victoria, Duncan Gillies, offering to advance the cause of Federation. Gillies's response was predictably cool, given the reluctance of Parkes to bring New South Wales into the Federal Council. In October Parkes travelled north to Brisbane and met with Griffith and Sir Thomas McIlwraith. On the return journey, he stopped just south of the colonial border, and delivered the historic Tenterfield Oration on 24 October 1889, stating that the time had come for the colonies to consider Australian federation.

Through the latter part of 1889, the premiers and governors corresponded and agreed for an informal meeting to be called. The membership was: New South Wales, Parkes (Premier) and William McMillan (Colonial Treasurer); Victoria, Duncan Gillies (Premier) and Alfred Deakin (Chief Secretary); Queensland, Sir Samuel Griffith (Leader of the Opposition) and John Murtagh Macrossan (Colonial Secretary); South Australia, Dr. John Cockburn (Premier) and Thomas Playford (Leader of the Opposition); Tasmania, Andrew Inglis Clark (Attorney-General) and Stafford Bird (Treasurer); Western Australia, Sir James George Lee Steere (Speaker); New Zealand, Captain William Russell (Colonial Secretary) and Sir John Hall.

When the conference met at the Victorian Parliament in Melbourne on 6 February, the delegates were confronted with a scorching summer maximum temperature of 39.7 °C (103.5 °F) in the shade. The Conference debated whether or not the time was ripe to proceed with federation.

While some of the delegates agreed it was, the smaller states were not as enthusiastic. Thomas Playford from South Australia indicated the tariff question and lack of popular support as hurdles. Similarly, Sir James Lee Steere from Western Australia and the New Zealand delegates suggested there was little support for federation in their respective colonies.

A basic question at this early assembly was how to structure the federation within the Westminster tradition of government. The British North America Act, 1867, which had confederated the Canadian provinces, provided a model with respect to the relations between the federation and the Crown. There was less enthusiasm, however, for the centralism of the Canadian Constitution, especially from the smaller states. Following the conference of 1890, the Canadian federal model was no longer considered appropriate for the Australian situation.[18]

Although the Swiss Federal Constitution provided another example, it was inevitable that the delegates should look to the Constitution of the United States as the other major model of a federation within the English-speaking world. It gave just a few powers to the federal government and left the majority of matters within the legislative competence of the states. It also provided that the Senate should consist of an equal number of members from each State while the Lower House should reflect the national distribution of population. Andrew Inglis Clark, a long-time admirer of American federal institutions, introduced the US Constitution as an example of the protection of States' rights. He presented it as an alternative to the Canadian model, arguing that Canada was "an instance of amalgamation rather than Federation."[19]

Clark's draft constitution[edit]

Andrew Inglis Clark had given considerable thought towards a suitable constitution for Australia.[20] In May 1890, he travelled to London to conduct an appeal on behalf of the Government of Tasmania before the Privy Council. During this trip, he began writing a draft constitution, taking the main provisions of the British North America Act, 1867 and its supplements up through 1890, the US Constitution, the Federal Council of Australasia Act, and various Australian colonial constitutions. Clark returned from London by way of Boston, Massachusetts, where he held discussions about his draft with Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., and Moncure Conway among others.[a]

Clark's draft introduced the nomenclature and form which was subsequently adopted:

- The Australian Federation is described as the Commonwealth of Australia

- There are three separate and equal branches – the Parliament, the Executive, and the Judicature.

- The Legislature consists of a House of Representatives and a Senate

- It specified the separation of powers and the division of powers between the Federal and State governments.

Upon his return to Hobart in early November 1890, with the technical aid of W. O. Wise, the Tasmanian Parliamentary Draftsman, Clark completed the final form of the Draft Constitution and had a number of copies printed.[21] In February 1891, Clark circulated copies of his draft to Parkes, Barton and probably Playford as well.[22] This draft was always intended to be a private working document, and was never published.[23]

The National Australasian Convention of 1891[edit]

The Parliament proposed at the Convention of 1891 was to adopt the nomenclature of the United States Congress; a House of Representatives and a Senate. The House of Representatives was to be elected by districts drawn up on the basis of their population, while in the Senate there was to be equal representation for each "province". This American model was mixed with the Westminster system by which the Prime Minister and other ministers would be appointed by the representative of the British Crown from among the members of the political party holding a majority in the lower House.

Griffith identified with great clarity at the Sydney Convention perhaps the greatest problem of all: how to structure the relationship between the lower and upper houses within the Federal Parliament. The main division of opinion centred on the contention of Alfred Deakin, that the lower house must be supreme, as opposed to the views of Barton, John Cockburn and others, that a strong Senate with co-ordinate powers was essential. Griffith himself recommended that the doctrine of responsible government should be left open, or substantially modified to accord with the Federal structure.

Over the Easter weekend in 1891, Griffith edited Clark's draft aboard the Queensland Government's steam yacht Lucinda. (Clark was not present, as he was ill with influenza in Sydney). Griffith's draft Constitution was submitted to colonial parliaments but it lapsed in New South Wales, after which the other colonies were unwilling to proceed.

Griffith or Clark?[edit]

The importance of the draft Constitution of 1891 was recognised by John La Nauze when he flatly declared that "The draft of 1891 is the Constitution of 1900, not its father or grandfather."[24] In the twenty-first century, however, a lively debate has sprung up as to whether the principal credit for this draft belongs to Queensland's Sir Samuel Griffith or Tasmania's Andrew Inglis Clark. The debate began with the publication of Peter Botsman's The Great Constitutional Swindle: A Citizen's Guide to the Australian Constitution[25] in 2000, and a biography of Andrew Inglis Clark by F.M. Neasey and L.J. Neasey published by the University of Tasmania Law Press in 2001.[26]

The traditional view attached almost sole responsibility for the 1891 draft to Griffith. Quick and Garran, for instance, state curtly that Griffith "had the chief hand in the actual drafting of the Bill".[27] Given that the authors of this highly respected work were themselves active members of the federal movement, it may be presumed that this view represents—if not the complete truth—then, at least, the consensus opinion among Australia's "founding fathers".

In his 1969 entry on "Clark, Andrew Inglis (1848–1907)" for the Australian Dictionary of Biography,[28] Henry Reynolds offers a more nuanced view:

Before the National Australasian Convention in Sydney in 1891 he [Clark] circulated his own draft constitution bill. This was practically a transcript of relevant provisions from the British North American Act, the United States Constitution and the Federal Council Act, arranged systematically, but it was to be of great use to the drafting committee at the convention. Parkes received it with reservations, suggesting that 'the structure should be evolved bit by bit'. George Higinbotham admitted the 'acknowledged defects & disadvantages' of responsible government, but criticized Clark's plan to separate the executive and the legislature. Clark's draft also differed from the adopted constitution in his proposal for 'a separate federal judiciary', with the new Supreme Court replacing the Privy Council as the highest court of appeal on all questions of law, which would be 'a wholesome innovation upon the American system'. He became a member of the Constitutional Committee and chairman of the Judiciary Committee. Although he took little part in the debates he assisted (Sir) Samuel Griffith, (Sir) Edmund Barton and Charles Cameron Kingston in revising Griffith's original draft of the adopted constitution on the Queensland government's steam yacht, Lucinda; though he was too ill to be present when the main work was done, his own draft had been the basis for most of Griffith's text.

Clark's supporters are quick to point out that 86 Sections (out of a total of 128) of the final Australian Constitution are recognisable in Clark's draft,[25] and that "only eight of Inglis Clark's ninety-six clauses failed to find their way into the final Australian Constitution";[29] but these are potentially misleading statistics. As Professor John Williams has pointed out:[30]

It is easy to point to the document and dismiss it as a mere 'cut and paste' from known provisions. While there is some validity in such observations it does tend to overlook the fact that there are very few variations to be added once the basic structure is agreed. So for instance, there was always going to be parts dealing with the executive, the parliament and the judiciary in any Australian constitution. The fact that Inglis Clark modelled his on the American Constitution is no surprise once that basic decision was made. Issues of the respective legislative powers, the role of the states, the power of amendment and financial questions were the detail of the debate that the framers were about to address in 1891.

As to who was responsible for the actual detailed drafting, as distinct from the broad structure and framework of the 1891 draft, John Williams (for one) is in no doubt:[30]

In terms of style there can be little argument that Inglis Clark's Constitution is not as crisp or clean as Kingston's 1891 draft Constitution. This is not so much a reflection on Inglis Clark, but an acknowledgement of the talents of Charles Kingston and Sir Samuel Griffith as drafters. They were direct and economical with words. The same cannot always be said of Inglis Clark.

Australasian Federal Convention of 1897–98[edit]

The apparent enthusiasm of 1891 rapidly ebbed in the face of opposition from Henry Parkes' rival, George Reid, and the sudden advent of the Labor Party in NSW, which commonly dismissed federation as a "fad".[31] The subsequent revival of the federal movement owed much to the growth of federal leagues outside of capital cities, and, in Victoria, the Australian Natives' Association. The Border Federation League of Corowa held a conference in 1893 which was to prove of considerable significance, and a "People's Convention" in Bathurst in 1896 underlined the cautious conversion of George Reid to the federal cause. At the close of the Corowa Conference John Quick had advanced a scheme of a popularly elected convention, tasked to prepare a constitution, which would then be put to a referendum in each colony. Winning the support of George Reid, premier of NSW from 1894, the Quick scheme was approved by all premiers in 1895. (Quick and Robert Garran later published The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth in 1901, which is widely regarded as one of the most authoritative works on the Australian Constitution.[32]) In March 1897 took place the Australasian Federal Convention Elections, and several weeks later the delegates gathered for the Convention's first session in Adelaide, later meeting in Sydney, and finally in Melbourne in March 1898. After the Adelaide meeting, the colonial Parliaments took the opportunity to debate the emerging Bill and to suggest changes. The basic principles of the 1891 draft constitution were adopted, modified by a consensus for more democracy in the constitutional structure. It was agreed that the Senate should be chosen, directly, by popular vote, rather than appointed by State governments.

On other matters there was considerable disagreement. 'Interests' inevitably fractured the unity of delegates in matters involving rivers and railways, producing legalistic compromises. And they had few guides, at a conceptual level, to what they were doing. Deakin greatly praised James Bryce's sage appreciation of American federalism, The American Commonwealth.[33] And Barton cited the analysis of federation of Bryce's Oxford colleagues, E.A. Freeman and A.V. Dicey.[34] But neither of these two writers could be said to be actual advocates of Federation. For delegates less given to reading (or citing) authors, the great model of plural governance would always be the British Empire,[35] which was no federation at all.

The Australasian Federal Convention dissolved on 17 March 1898 having adopted a bill "To Constitute the Commonwealth of Australia".

Referendums on the proposed constitution were held in four of the colonies in June 1898. There were majority votes in all four, however, the enabling legislation in New South Wales required the support of at least 80,000 voters for passage, equivalent to about half of enrolled voters, and this number was not reached.[36] A meeting of the colonial premiers in early 1899 agreed to a number of amendments to make the constitution more acceptable to New South Wales. These included the limiting "Braddon Clause", which guaranteed the states 75 percent of customs revenue, to just ten years of operation; requiring that the new federal capital would be located in New South Wales, but at least a hundred miles (160 km) distant from Sydney;[36] and, in the circumstances of a "double dissolution", reducing from six tenths to one half the requisite majority to legislate of a subsequent joint meeting of Senate and House . In June 1899, referendums on the revised constitution were again held again in all the colonies except for Western Australia, where the vote was not held until the following year. The majority vote was "yes" in all the colonies.

1898 referendums[edit]

| State | Date | For | Against | Total | Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| Tasmania | 3 June 1898 | 11,797 | 81.29 | 2,716 | 18.71 | 14,513 | 25.0 |

| New South Wales | 3 June 1898 | 71,595 | 51.95 | 66,228 | 48.05 | 137,823 | 43.5 |

| Victoria | 3 June 1898 | 100,520 | 81.98 | 22,099 | 18.02 | 122,619 | 50.3 |

| South Australia | 4 June 1898 | 35,800 | 67.39 | 17,320 | 20.54 | 53,120 | 30.9 |

| Source: Federation Fact Sheet 1 – The Referendums 1898–1900, AEC and Australia's Constitutional Milestones, APH | |||||||

1899 and 1900 referendums[edit]

| State | Date | For | Against | Total | Turnout | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | ||||

| South Australia | 29 April 1899 | 65,990 | 79.46 | 17,053 | 20.54 | 83,043 | 54.4 |

| New South Wales | 20 June 1899 | 107,420 | 56.49 | 82,741 | 43.51 | 190,161 | 63.4 |

| Tasmania | 27 July 1899 | 13,437 | 94.40 | 791 | 5.60 | 14,234 | 41.8 |

| Victoria | 27 July 1899 | 152,653 | 93.96 | 9,805 | 6.04 | 162,458 | 56.3 |

| Queensland | 2 September 1899 | 38,488 | 55.39 | 30,996 | 44.61 | 69,484 | 54.4 |

| Western Australia | 31 July 1900 | 44,800 | 69.47 | 19,691 | 30.53 | 64,491 | 67.1 |

| Source: Federation Fact Sheet 1 – The Referendums 1898–1900, AEC and Australia's Constitutional Milestones, APH | |||||||

The bill as accepted by the colonies (except Western Australia, which voted after the act was passed by the British parliament) went to Britain for legislation by the British Parliament.

Federal Constitution[edit]

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK) was passed on 5 July 1900[37] and given Royal Assent by Queen Victoria on 9 July 1900.[38] It was proclaimed on 1 January 1901 in Centennial Park, Sydney. Sir Edmund Barton was sworn in as the interim Prime Minister, leading an interim Federal ministry of nine members.[citation needed]

The new constitution established a bicameral Parliament, containing a Senate and a House of Representatives. The office of Governor-General was established as the Queen's representative; initially, this person was considered a representative of the British Government.[citation needed]

The Constitution also provided for the establishment of a High Court, and divided the powers of government between the states and the new Commonwealth government. The states retained their own parliaments, along with the majority of existing powers, but the federal government would be responsible of issues defence, immigration, quarantine, customs, banking and coinage, among other powers.[39][40]

Landmarks named after Federation[edit]

The significance of Federation for Australia is such that a number of landmarks, natural and man-made, have been named after it. These include:

- Federal Highway, between Goulburn, New South Wales and Canberra

- Federation Creek, near Croydon, Queensland

- Federation Peak, Tasmania

- Federation Range, on the Royston River, about 90 kilometres (56 mi) east-northeast of Melbourne, Victoria

- Federation Square, Melbourne, Victoria[41]

- Federation Trail, Melbourne, Victoria

- Federation University, Ballarat, Victoria

See also[edit]

- Government of Australia

- Federalism in Australia

- Australian Capital Territory

- Secessionism in Western Australia

- History of monarchy in Australia

- Australian nationality law

- Australian Bicentenary

- Federation Drought

Notes[edit]

- ^ Clark, Conway and Holmes were all Unitarians. Clark had met Conway when he travelled to Hobart, Tasmania, as part of his speaking tour in 1883. Conway later introduced Clark to Holmes.

References[edit]

- ^ "Fiji and Australian Federation. – (From the Herald's own Correspondent.) Melbourne, Monday". The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser. 25 October 1883. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Lloyd, Peter (June 2015). "Customs Union and Fiscal Union in Australia at Federation". Economic Record. 91 (293): 155–171. doi:10.1111/1475-4932.12167. S2CID 153972430.

- ^ Varian, Brian D.; Grayson, Luke H. (March 2024). "Economic Aspects of Australian Federation: Trade Restrictiveness and Welfare Effects in the Colonies and the Commonwealth, 1900-3". Economic Record. 100 (328): 74–100. doi:10.1111/1475-4932.12790.

- ^ "UNION OF THE SOUTHERN COLONIES UNDER A GOVERNOR-GENERAL". Southern Australian. 10 June 1842. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Serle, Percival. "Fitzroy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ Ross, Thomas. "Rulers: Regal and Vice-Regal". Colony and Empire. Archived from the original on 19 June 2004. Retrieved 19 June 2004.

- ^ Ward, John M. "FitzRoy, Sir Charles Augustus (1796–1858)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- ^ Tony Stephens, "Proud town's key role in our destiny", Sydney Morning Herald, 26 December 2000, p. 10

- ^ a b c Tink, Andrew (2009). William Charles Wentworth : Australia's greatest native son. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-192-5 – via Trove.

- ^ Votes & Proceedings, Volume 1. New South Wales: New South Wales Legislative Council. 1849. p. 9.

- ^ Osborne, M. E. "Thomson, Sir Edward Deas (1800–1879)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 521.

- ^ note 2, at 18–21.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, p159.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, pp 196–7.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, p.43, p.152.

- ^ Martin, Henry Parkes, at 383.

- ^ Williams J, "'With Eyes Open': Andrew Inglis Clark and our Republican Tradition" (1995) 23(2) Federal Law Review 149 at 165.

- ^ Debates of the Australian Federation Conference, at 25.

- ^ As early as 1874, he published a comparative study of the American, Canadian and Swiss constitutions.

- ^ Letter from W. O. Wise to A. P. Canaway dated 29 June 1921. Cover page to First draft of Australian Constitution. Mitchell Library MS, Q342.901

- ^ Neasey, F. M.; Neasey, L. J. (2001). Andrew Inglis Clark. University of Tasmania Law Press. ISBN 0-85901-964-0.

- ^ La Nauze, page 24

- ^ La Nauze, note 11 at 78.

- ^ a b Botsman, Peter (2000). The Great Constitutional Swindle. Pluto Press Australia. p. 19. ISBN 1-86403-062-3.

- ^ Neasey, F.M.; Neasey, L.J. (2001). Andrew Inglis Clark. Hobart: University of Tasmania Law Press.

- ^ Quick, John; Garran, Robert Randolph (1901). The annotated constitution of the Australian Commonwealth. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. p. 130.

- ^ Reynolds, Henry (1969). "Clark, Andrew Inglis (1848 -1907)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Neasey, Frank (1991). "Andrew Inglis Clark and Australian Federation". Papers on Parliament. 13.

- ^ a b Williams, John (Professor) (2014). "Andrew Inglis Clark: Our Constitution and His Influence". Papers on Parliament. 61.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, p84.

- ^ "Closer Look: The Australian Constitution". Parliamentary Education Office. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ La Nauze, J. A. (1972). The Making of the Australian Constitution. Melbourne University Press. p. 273. ISBN 0-522-84016-7.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, pp 152–155.

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021, p402.

- ^ a b "Celebrating Federation" (PDF). Constitutional Centre of Western Australia. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Commonwealth Of Australia Constitution Bill – Hansard – UK Parliament". UK Parliament. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900". legislation.gov.uk. British Government. 9 July 1900. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Three levels of government: governing Australia". Parliamentary Education Office. 19 January 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "The roles and responsibilities of the three levels of government". Parliamentary Education Office. 29 June 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Explore the Fascinating History of Federation Square". Fed Square Pty Ltd. 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

Bibliography[edit]

- La Nauze, J, The Making of the Australian Constitution (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1972).

- McGrath, F, The Framers of the Australian Constitution (Brighton-le-Sands: Frank McGrath, 2003).

- Neasey, F. M.; Neasey, L. J. Andrew Inglis Clark. (University of Tasmania Law Press, 2001)

Further reading[edit]

- Baker, Richard Chaffey (1891). A Manual Of Reference To Authorities For The Use Of The Members Of The National Australasian Convention Which Will Assemble At Sydney On March 2, 1891 For The Purpose Of Drafting A Constitution For The Dominion of Australia (PDF). Adelaide: W.K. Thomas & Co.

- Bennet, Scott Cecil (1969). Annotated documents on the making of the Commonwealth of Australia (PDF). Australian National University.

- Cockburn, John A. (1905). . The Empire and the century. London: John Murray. pp. 446–461.

- [1]

- Hunt, Lyall (editor) (2000)Towards Federation: Why Western Australia joined the Australian Federation in 1901 Nedlands, W.A. Royal Western Australian Historical Society ISBN 0-909845-03-4

- McQueen, Humphrey, (1970/2004), A New Britannia, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane.

- Arthur Patchett Martin (1889). "Australian Democracy". Australia and the Empire: 77–114. Wikidata Q107340686.

- Quick, John, Historical Introduction to The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth (Sydney: University of Sydney Library, 2000)

- Deakin, Alfred, 1880–1900 (Legislative Assembly politician) The Federal Story, The Inner History of the Federal Cause, Deakin 175 page eyewitness report. Edited by J. A. La Nauze published by Melbourne University Press.

- Wise, Bernard Ringrose (1913). The Making of The Australian Commonwealth. Longmans, Green, and Co.

External links[edit]

- Federation and the Constitution – resource of the National Archives of Australia

- Records of the Australasian Federal Conventions of the 1890s

- Australian Federation Full Text Database – primary source material

v

- ^ William Coleman,Their Fiery Cross of Union. A Retelling of the Creation of the Australian Federation, 1889–1914, Connor Court, Queensland, 2021.