Cyclone Chapala

| Extremely severe cyclonic storm (IMD scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

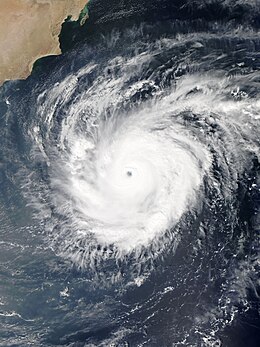

Chapala during peak intensity on 30 October | |

| Formed | 28 October 2015 |

| Dissipated | 4 November 2015 |

| Highest winds | 3-minute sustained: 215 km/h (130 mph) 1-minute sustained: 240 km/h (150 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 940 hPa (mbar); 27.76 inHg |

| Fatalities | 9 confirmed |

| Damage | Unknown |

| Areas affected | Oman, Somalia, Yemen |

| Part of the 2015 North Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Chapala[nb 1] (Template:Lang-ar, iiesar tashabalaan; Arabic pronunciation: [i̠ʕsˤäː ɾ taʃaː balaː]) was the second strongest tropical cyclone on record in the Arabian Sea, according to the American-based Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC). The third named storm of the 2015 North Indian Ocean cyclone season, it developed on 28 October off western India from the monsoon trough. Fueled by record warm water temperatures, the system quickly intensified and was named Chapala by the India Meteorological Department (IMD). By 30 October, the storm developed an eye in the center of a well-defined circular area of deep convection. That day, the IMD estimated peak three-minute sustained winds of 215 km/h (130 mph), and the JTWC estimated one-minute winds of 240 km/h (150 mph); only Cyclone Gonu in 2007 was stronger in the Arabian Sea.

After peak intensity, Chapala skirted the Yemeni island of Socotra on 1 November. Drier air and increased wind shear weakened the cyclone, although it maintained much of its intensity upon entering the Gulf of Aden on 2 November, becoming the strongest known cyclone in that body of water. After bypassing northern Somalia, Chapala weakened further and turned to the west-northwest. Early on 3 November, the storm made landfall near Al Mukalla, Yemen, as a very severe cyclonic storm, making it the strongest storm on record to strike the nation. The storm dissipated the next day.

The cyclone first affected Socotra, becoming the first hurricane-force storm there since 1922. High winds and heavy rainfall resulted in an island-wide power outage, and severe damage was compounded by Cyclone Megh just days later. Chapala brushed the northern coast of Somalia, killing thousands of animals and wrecking 250 houses. One person drowned off the coast when a boat capsized amid the storm. Ahead of the cyclone's final landfall, widespread evacuations occurred across southeastern Yemen, including in areas controlled by al-Qaeda, amid the country's ongoing civil war. Heavy rainfall – the equivalent to several years' worth – inundated coastal areas, which damaged or destroyed roads and hundreds of homes. Eight people died in Yemen, a low total credited to the evacuations, and another 65 were injured. After the storm and later Cyclone Megh, various countries, non-government organizations, and agencies within the United Nations provided monetary and material assistance to Yemen. The country faced food and fuel shortages, and residual storm effects contributed to an outbreak of locusts and dengue fever, the latter of which killed seven people.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A trough developed along the northeast monsoon on 25 October 2015 off the southwest coast of India,[2] consisting of a fragmented area of convection, or thunderstorms. The system was located within an environment of moderate wind shear, which prevented early development, although conditions were anticipated to become more favorable.[3] On 26 October, the system developed a distinct low pressure area.[2] The low gradually consolidated,[2] and the circulation became better defined, amplified by decreasing wind shear and good outflow to the north and south.[4] At 03:00 UTC on 28 October, the India Meteorological Department (IMD)[nb 2] designated the system as a depression. Nine hours later, the agency upgraded it further to a deep depression,[2] and the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC)[nb 3] classified the system as Tropical Cyclone 04A at 21:00 UTC.[7]

Initially, the storm moved slowly to the north due to a ridge to the northeast, although the track shifted to the west due to another ridge to the northwest.[2] With record warm water temperatures for the time of year[8] – reaching 30 °C (86 °F) – as well as favorable conditions related to the Madden–Julian oscillation, the system rapidly intensified beginning on 29 October. At 00:00 UTC that day, the IMD upgraded the system to a cyclonic storm, giving it the name Chapala.[2] The storm developed well-defined rainbands as the structure consolidated more, with well established outflow to the north and south. An eye began developing,[9] prompting the JTWC to upgrade Chapala to the equivalence of a hurricane, with one-minute maximum sustained winds of 120 km/h (75 mph), at 12:00 UTC on 29 October.[10] Meanwhile, the IMD upgraded Chapala to a severe cyclonic storm at 09:00 UTC that day, and further to a very severe cyclonic storm at 18:00 UTC.[2] By early on 30 October, Chapala had developed a well-defined eye 22 km (14 mi) wide, amplified by vigorous outflow and continued low wind shear. Based on satellite intensity estimates from the Dvorak technique, the JTWC assessed Chapala as a high-end Category 4-equivalent cyclone on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale at 06:00 UTC with one-minute sustained winds of 240 km/h (150 mph).[11] Based on their estimate, Chapala was the second-strongest cyclone on record over the Arabian Sea; only Cyclone Gonu of 2007 was stronger.[12] Meanwhile, the IMD upgraded the system to an extremely severe cyclonic storm at 00:00 UTC on 30 October, and estimating peak three-minute sustained winds of 210 km/h (130 mph) at 09:00 UTC.[2] During this time, the storm was moving to the west-southwest due to the ridge to the north.[2]

Initially, the IMD expected Chapala would intensify further into a super cyclonic storm,[13] and the JTWC anticipated it would strengthen to the equivalent of a Category 5-equivalent on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[11] However, the storm began an eyewall replacement cycle on 30 October, causing the inner eyewall to degrade and for an outer eyewall to form; this resulted in a slight drop in intensity.[2] In addition, drier air began affecting the storm, causing the thunderstorms around the eye to diminish.[14] However, Chapala maintained much of its intensity due to strong outflow in all directions,[2] especially to the northeast due to a tropical upper tropospheric trough over India,[14] despite increased wind shear.[15] On 31 October, the outer eyewall became established, reaching a diameter of 37 km (23 mi), although the thunderstorms around the eye continued to weaken.[2] On 1 November, Chapala passed just north of the island of Socotra,[16] marking the area's first hurricane-force impact since 1922.[17]

After the cyclone bypassed Socotra, its convective core became better defined due to improved outflow.[18] On 2 November, Chapala entered the Gulf of Aden, becoming the strongest tropical cyclone on record in that region.[19][20] At 12:00 UTC that day, the IMD downgraded the system to a very severe cyclonic storm, after Chapala had been an extremely severe cyclonic storm for 78 hours.[2] The structure became disorganized that day due to increased easterly wind shear and interaction with the Arabian Peninsula to the north,[21] causing cooler and drier air to enter the circulation. Around this time, the storm began moving more to the west-northwest toward Yemen, rounding the southwestern periphery of a ridge.[2] Between 01:00–02:00 UTC on 3 November, Chapala made landfall near Al Mukalla with winds of 120 km/h (75 mph).[2] This marked the first hurricane-intensity landfall for Yemen on record,[22] and the first severe cyclonic storm to hit the country since May 1960.[2] According to the JTWC, Chapala moved ashore and immediately turned back over water,[23] although the agency soon reassessed the center as being over land.[24] Chapala quickly weakened over land, degenerating into a depression by 00:00 UTC on 4 November, and weakening into a remnant low pressure area three hours later.[2]

Preparations and impact

Oman

By 30 October, well ahead of the storm, officials in Oman warned for the potential of flash flooding and high waves along the coast.[25] The public was advised to stay away from low-lying areas. Fishermen were asked to avoid venturing into the sea,[26] due to the potential for waves reaching 5 to 7 m (16 to 23 ft) in height.[25] Officials closed schools in Dhofar Governorate.[25] The storm ultimately passed the country to the southwest, sparing the feared impacts from the cyclone. But first it was expected to hit Salalah,Oman. All because of the wind direction change, the wind movement of the cyclone moved towards Yemen.[27]

Somalia

Ahead of the storm, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees advised migrants and refugees from Somalia and Ethiopia from crossing to Yemen due to anticipated rough seas from Chapala.[28] An Iranian-flagged vessel capsized offshore on 1 November, killing one person and leaving many others missing.[29] Large swells produced by Chapala caused extensive coastal damage in Somalia,[30] damaging 280 boats.[31] Nationwide, the storm wrecked 350 houses,[31] leaving thousands of residents homeless.[30] Eastern Puntland was hardest-hit,[30] where 45 km (28 mi) of roads were damaged.[31] Also in Puntland, the cyclone blew away the roofs of 28 classrooms in schools, forcing students to continue learning in tents.[32] In the Bari region, the storm killed 25,000 animals and downed 5,100 trees.[31] Heavy rainfall from the storm spread to the northeastern tip of Somalia,[8] and westward to the Berbera District in Somaliland. There, the rains killed 3,000 sheep and goats, as well as 200 camels; this severely affected the local nomadic population who rely on the livestock for their livelihood.[33] Continuous rainfall forced families to leave their homes in low-lying areas to higher grounds.[34]

After the storm, the government of Somaliland distributed rice, sugar, and plastic sheets for housing.[35] After Chapala and the subsequent Cyclone Megh, the local Red Cross chapter distributed blankets, sleeping mats, and mattresses to the affected families.[36] The CARE relief agency provided US$300,000 toward restoring water and relief goods.[31]

Yemen

Cyclone Chapala was slated to be the strongest tropical cyclone ever to affect Yemen, and this sparked fears of catastrophic flooding amid the ongoing civil war.[26] The United Nations indicated that Yemen was in the midst of "one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world."[12] Rainfall was forecast to total more than several years' worth of precipitation in some areas, bringing fears of "massive debris flows and flash flooding."[12] Some weather models showed peak accumulations of 400 mm (16 in) or more. Fears of damage and loss of life were compounded by the power vacuum in areas controlled by al-Qaeda—the Yemeni Army and Government withdrew from areas in April—particularly the port city of Al Mukalla where approximately 300,000 people live.[17]

The internationally recognized government, which controls most of southern Yemen, announced the suspension of schools in four governorates: Hadhramaut, Socotra, Al Mahrah and Shabwah.[26] By 1 November, evacuations were ordered in Al Mukalla and Hadhramaut,[37] and the government's meteorological agency recommended residents to stay more than one kilometre from the coastline.[38] About 18,750 people left their homes ahead of the storm on the Yemen mainland.[39] Most people sheltered in public buildings like schools or hospitals, or stayed with relatives.[40] There were reports that al-Qaeda evacuated residents near the coast in Al Mukalla immediately before the storm struck.[41] Ahead of the storm, the World Health Organization distributed gasoline to ambulances and hospitals to ensure they would continue operating effectively.[42]

Socotra

On the offshore Socotra island, over 1,000 families evacuated to schools set up as shelters.[43] On 1 November, Chapala became the first hurricane-force storm to impact Socotra since 1922,[17] bringing strong winds and heavy rainfall. Residents reported rainfall to be the most severe in decades,[37][44] and northeastern areas of the island were rendered inaccessible due to flooding,[12] forcing residents to ride out the storm on their roofs.[41] Chapala damaged Socotra's main port,[45] and also caused an island-wide power outage.[41] Chapala wrecked 237 homes on the island and damaged at least 497 homes,[41][46] forcing about 18,000 people to leave their homes.[40] Initial reports indicated that three people were killed and at least 200 others sustained injuries on the island; subsequently, the government reported that there were no deaths on the island.[17][41][47]

Mainland

High winds, strong waves and heavy rainfall affected the southern Yemen coast.[45] At Riyan Airport, the weather station reported sustained winds of 117 km/h (73 mph) with gusts to 143 km/h (89 mph), before it stopped recording data; the continued increase in winds supported that Chapala made landfall in Yemen as the equivalent of a hurricane.[48] Areas in the region received 610 mm (24 in) of rainfall over 48 hours, or 700% of the average yearly precipitation.[45] As the area usually receives less than 50 mm (2 in) of rainfall per year, the grounds did not absorb much of the waters. This caused flash flooding and widespread inundation,[41] which collected along wadis, or typically dry river beds, and flooded coastal areas several kilometres inland.[49] Floods covered the nation's fifth-largest city, Al Mukalla,[45] where the storm severed phone lines,[41] disrupted water access after damaging pipes,[50] and damaged 90 houses.[51] Residents in Al Mukalla took shelter in schools as the storm caused the sea level to rise by 9 m (30 ft), destroying the city's seafront.[52] The city's main hospital was closed after it was flooded, but it was reopened two days later.[53] Chapala damaged seven health facilities.[54] About 35 km (22 mi) of primary and secondary roads in and around Al Mukalla were littered with mud due to the floods and landslides, including the coastal road from Aden to the city.[46]

Elsewhere, about 80% of the village of Jilah was flooded,[55] damaging 250 houses.[56] Flooding from Chapala also damaged crops, killed livestock, and wrecked boats.[45] The storm destroyed 214 homes and damaged another 600 on the Yemen mainland.[45] The storm caused eight deaths – five by drowning and three from collapsed homes.[57][58] One of the deaths occurred as far west as Aden, when a fisherman drowned amid rough seas.[59] About 65 additional people were injured,[60] including 25 in Al Mukalla.[51] Officials credited the low death toll to the widespread evacuations ahead of the storm.[61] Collectively, the passages of Chapala and Megh near Socotra and mainland Yemen killed 26 people and displaced 47,000 people.[62]

Aftermath

The Yemeni Government declared a state of emergency for Socotra shortly after the storm's passage on 1 November.[63] The local Red Cross gave cooked meals and tarps to the island's residents.[64] Various Persian Gulf countries sent 43 planes with supplies to the island by 19 November.[50] Neighboring Oman sent 14 cargo planes' worth of food totaling 270 tons worth of goods. The planes mostly carried food,[60] as well as blankets and tents.[59] The United Arab Emirates also sent a ship and a plane, carrying 500 tons of food, 10 tons of blankets and tents, and 1,200 barrels of food.[65] The International Organization for Migration provided 2,000 shelter kits as well as a medical team to Socotra.[66] Due to damage to the island's main port, residents built a makeshift pathway to help distribution of aid.[67]

In the days after the storm, airstrikes and attacks continued elsewhere in the country,[46] and only days after Chapala, Cyclone Megh followed a similar path, causing additional damage.[68] Relief distribution was disrupted due to the poor communications in the region, worsened by the ongoing civil war,[41] with the hardest hit areas under al-Qaeda control;[45] aid trucks had to pass security clearances, resulting in delays.[55] Workers began restoring communications and clearing roads in the days after the storm.[60] By 19 November, most of the displaced residents had returned home, although some remained in shelters due to house damage.[50] Southern portions of Yemen saw food and fuel shortages following the two storms.[69] Al Mukalla experienced an outbreak of dengue fever by January 2016 due to the floods, affecting 1,040 people; earlier efforts to kill disease carrying mosquitoes were ineffective due to residual floods and unsanitary conditions. Seven people died due to the outbreak.[70] A locust outbreak also began in December 2015 due to the floods.[71]

Agencies under the United Nations and non-government organizations provided assistance to the storm victims,[46] although aid agencies were cautious in helping a city under control of Al Qaeda.[70] The Red Crescent Society of the United Arab Emirates, in conjunction with the Khalifa Foundation and the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre, provided aid to the hardest hit areas of mainland Yemen via an airbridge,[72] as well as over land.[46] United Nations agencies sent 29 trucks carrying 296 tons of non-food items, and the World Health Organization sent a ship from Djibouti with 18 tons of medical supplies.[73] To prevent the spread of disease, officials began mass immunizing children under five years old, as well as distributing mosquito nets.[60] A national effort to vaccinate against polio was disrupted in six governorates by the cyclone, but was completed by December.[74] Médecins Sans Frontières established a medical clinic in Al Mukalla while also setting up a water tank.[75] To help with food shortages, the World Food Programme had provided High Energy Biscuits by 30 November to 24,900 people, using pre-stocked supplies.[76] The International Organization for Migration provided 41,000 L (11,000 US gal) of water per day in Shabwah and Abyan governorates,[66] and also helped clean sewage and debris from the storm.[77] Agencies also delivered hygiene kits and food to the hardest hit areas.[45] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees provided emergency beds, cooking utensils, and other supplies to about 1,600 families.[28]

See also

Notes

- ^ The name Chapala was suggested by Bangladesh; it is a girl's name, meaning "restless" in Bangla.[1]

- ^ The India Meteorological Department is the official Regional Specialized Meteorological Center for the northern Indian Ocean.[5]

- ^ The Joint Typhoon Warning Center is a joint United States Navy – United States Air Force task force that issues tropical cyclone warnings for the Indian Ocean and other regions.[6]

References

- ^ "Meaning of Bengali Girl Name Chapala". Modern Indian Baby Names. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm, Chapala over the Arabian Sea (28 October - 04 November 2015): A Report (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. December 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Significant Tropical Weather Advisory". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Significant Tropical Weather Advisory". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 26 October 2015. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ RSMC New Delhi. Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (RSMC) – Tropical Cyclones, New Delhi (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2011. Archived from the original on 26 July 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Four) Warning Nr 001 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 28 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Keith Cressman. Tropical Cyclone Chapala 28 October 2015 - 4 November 2015 (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization (Report). ReliefWeb. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 003 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 004 (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 007. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Jethro Mullen (2 November 2015). "Rare cyclone poses new worries for war-torn Yemen". CNN. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Mohapatra, M (30 October 2015). Tropical Storm Chapala Advisory 13 issued at 1500 UTC of 30 October 2015 (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 009. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 012. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 015. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1 November 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Derek Baldwin (2 November 2015). "Cyclone Chapala to dump 400mm of rainfall in Yemen". Gulf News. Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 017. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 1 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mogul, Priyanka. "Cyclone Chapala: Rare tropical storm makes landfall over Yemen, killing three". International Business Times. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Cyclone Chapala nearing landfall over Yemen". Met Office News Blog. Met Office News Blog. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 021. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 2 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bob Henson (3 November 2015). "Chapala Slams Yemen: First Hurricane-Strength Cyclone on Record". Weather Underground. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 023. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tropical Cyclone 04A (Chapala) Warning Nr 024. Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). United States Navy. 3 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "'Extremely severe' cyclone heading for Yemen, Oman: UN". ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b c Rai, Bindu (1 November 2015). "Cyclone Chapala: 30ft high waves; Schools suspended; Oman, Yemen on high alert". emirates24-7. emirates24-7. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ NMHEWS End of Chapala Direct Impacts. Government of Oman (Report). ReliefWeb. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b UNHCR provides emergency relief to cyclone-displaced in Yemen. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (Report). ReliefWeb. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Warka (3 November 2015). "Somalia: One person dies as illegal fishing vessel capsizes in Puntland". Mareeg.com. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b c "Cyclone leaves thousands homeless in Somalia". Mogadishu, Somalia: news24. 3 November 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e The Humanitarian Coalition and CARE Canada help cyclone survivors in Somalia (PDF). CARE (Report). ReliefWeb. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ UNICEF Somalia Humanitarian Situation Report 11, November 2015 (PDF). UNICEF (Report). ReliefWeb. 30 November 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Somalia: Tropical Cyclone Chapala Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) DREF Operation ° MDRSO004. International Federation of Red Cross And Red Crescent Societies (Report). ReliefWeb. 14 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "Somaliland: Government Distributes Relief Aid to Storm affected Bulahaar residents". Somaliland Press. 7 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "In Somaliland, climate change is now a life-or-death challenge". The Guardian. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Somalia: Tropical Cyclone Chapala (PDF). International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (Report). ReliefWeb. 14 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b Ahmed Al-Haj (1 November 2015). "Yemen's Socotra Island hit by rare cyclone". Sanaa, Yemen: WAVY-TV. Associated Press. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Oman, Yemen warn coastal areas as severe cyclone approaches". ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Yemen: Cyclone Chapala Flash Update 1 (PDF). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). 3 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b Annie Slemrod (5 November 2015). "Will Yemen's storm yet prove disastrous?". ReliefWeb. IRIN. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Yemen's curse: civil war, bombs, and now floods". ReliefWeb. IRIN. 3 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ WHO scales up response in Yemen for cyclone Chapala. World Health Organization (Report). ReliefWeb. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ "Yemeni island lashed as cyclone heads for mainland". ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 1 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Mohammed Al Qalisi (2 November 2015). "One dead as Cyclone Chapala slams into Socotra". The National World. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yemen: Cyclone Chapala Flash Update (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 4 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Yemen: Cyclone Chapala Flash Update 3 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 5 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Panic, deaths as Yemen's Socotra hit by new cyclone". PHYS.ORG. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ Bob Henson (3 November 2015). "Chapala Slams Yemen: First Hurricane-Strength Cyclone on Record". Weather Underground. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ Chapala Drenches the Desert. ReliefWeb. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Yemen: Cyclones Chapala and Megh Flash Update 11 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 19 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b Yemen - Tropical Cyclone CHAPALA (ECHO, OCHA, WFP, Log Cluster, Media) (ECHO Daily Flash of 5 November 2015). European Commission Humanitarian Aid Office (Report). ReliefWeb. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Cyclone Chapala bears down on mainland Yemen". BBC. 3 November 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Yemen: TC Chapala -The map shows reports on casualties in affected areas (11 Nov 2015) (PDF). MapAction (Report). ReliefWeb. 11 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen conflict Situation report #18, 26 October - 9 November 2015 (PDF). World Health Organization (Report). ReliefWeb. 9 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ a b Yemen Situation Update (12 November 2015) (PDF). World Food Programme (Report). ReliefWeb. 12 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen: Cyclones Chapala and Megh Flash Update 9 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 13 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "8 killed in Yemen cyclone storm: Official". Middle East Eye. Middle East Eye. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Yemen – Storm Chapala Leaves 3 Dead, 35 Injured and 40,000 Displaced". Floodlist. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Aid from neighbours reaches Yemen as cyclone eases". ReliefWeb. Agence France-Presse. 4 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Yemen: Cyclone Chapala Flash Update 5 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 8 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen: Cyclone Chapala Flash Update 4 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 6 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Humanitarian Bulletin Yemen Issue 5 (PDF). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). ReliefWeb. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ "عشرات الضحايا ونزوح الآلآف من سقطرى اليمنية بسبب "شابالا"". arabiaweather.com (in Arabic). 1 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ Yemen: Tropical cyclones compound humanitarian suffering. International Committee of the Red Cross (Report). ReliefWeb. 20 November 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "Khalifa Foundation sends aid to Socotra Archipelago". ReliefWeb. Emirates News Agency. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b Yemen Crisis: IOM Regional Response - Situation Report, 3 December 2015 (PDF). International Organization for Migration (Report). ReliefWeb. 3 December 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen: Cyclones Chapala and Megh Flash Update 8 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 11 November 2015. ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm, Megh over the Arabian Sea (05-10 November 2015): A Report (PDF) (Report). India Meteorological Department. December 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Yemen Market Situation Update Weeks 1 and 2: November 2015 (PDF). World Food Programme (Report). ReliefWeb. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b Saeed Al Batati (4 January 2016). "Dengue fever spreads in Yemeni city ravaged by cyclone". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 (PDF). United States Agency for International Development (Report). ReliefWeb. 30 December 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen - Tropical Cyclone CHAPALA (ECHO, GDACS, JTWC, NMS, NASA, Media) (ECHO Daily Flash of 3 November 2015). European Commission Humanitarian Aid Office (Report). ReliefWeb. 3 November 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ^ Yemen Situation Update (18 November 2015) (PDF). World Food Programme (Report). ReliefWeb. 18 November 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ UNICEF Yemen Crisis Humanitarian Situation Report (21 November - 3 December 2015). UNICEF (Report). ReliefWeb. 3 December 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Yemen: Aiding People Affected by Cyclones in Hadhramaut Province. Médecins Sans Frontières (Report). ReliefWeb. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ WFP Yemen Situation Report #18, 13 December 2015 (PDF) (Report). ReliefWeb. 15 December 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ Yemen Crisis: IOM Regional Response - Situation Report, 7 January 2016 (PDF). International Organization for Migration (Report). ReliefWeb. 7 January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.