Daniel Morgan

Daniel Morgan | |

|---|---|

| |

| In office March 4, 1797—March 3, 1799 | |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Height | 200px |

| Spouse | Abigail Curry[1] |

Daniel Morgan (1736 – July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and United States Representative from Virginia. One of the most gifted battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War, he later commanded troops during the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion.

Early years

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2008) |

Most authorities believe that Morgan was born in Hunterdon County, New Jersey. His parents were Welsh immigrants. Morgan was the fifth of seven children of Joseph Morgan (1702–1748) and Elizabeth Lloyd (1706–1748). When Morgan was 16, he left home following a fight with his father. After working at odd jobs in Pennsylvania, he moved to the Shenandoah Valley. He finally settled on the Virginia frontier, near what is now Winchester, Virginia.

Morgan was a large man, poorly educated, and enjoyed drinking and gambling. He worked clearing land, in a sawmill, and as a teamster. In just a year, he saved enough to buy his own team. Morgan had served as a civilian teamster during the French and Indian War. During the advance on Fort Pitt by General Braddock's command, he was punished with 499 lashes (a usually fatal event) for punching his superior officer. Morgan thus acquired a hatred for the British Army.

He later served as a rifleman in the Provincial forces assigned to protect the western border settlements from French-backed Indian raids. Some time after the end of the war, he purchased a farm situated between Winchester and Battletown. By 1774 he had grown so prosperous that he owned ten slaves.[2] That year he served in Dunmore's War taking part in raids on Shawnee villages in the Ohio Country.

American Revolution

After the American Revolutionary War began at the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, the Continental Congress created the Continental Army. They called for the formation of 10 rifle companies from the middle colonies to support the Siege of Boston, and late in June of 1775 Virginia agreed to send two. The Virginia House of Burgesses chose Daniel Morgan to form one of these companies and serve as its commander with the rank of captain. Morgan had served as an officer in the Virginia Colonial Militia since the French and Indian War. He recruited 96 men in 10 days and assembled them at Winchester on July 14. He then marched them 600 miles (970 km) to Boston, Massachusetts in only 21 days, arriving on Aug. 6, 1775.[3] He led this outstanding group of marksmen nicknamed "Morgan's Riflemen."

The invasion of Canada

Later in 1775, Congress authorized an invasion of Canada. Colonel Benedict Arnold convinced General Washington to send an eastern offensive in support of Montgomery's invasion. Washington agreed to send three rifle companies from among his forces at Boston, if they volunteered. All of the companies at Boston volunteered, so lotteries were used to choose who should go, and Morgan's company was among those chosen. Arnold selected Captain Morgan to lead all three companies as a unit. The expedition set out from Fort Western on Sept. 25, with Morgan's men leading the advance party.[4]

At the start, the Arnold Expedition had about 1,000 men, but by the time they arrived near Quebec on Nov. 9 it had been reduced to 600. (Note: historians have never reached a consensus on the use of a standard name for this epic journey.) When Montgomery arrived, they launched their disastrous assault, the Battle of Quebec, on the morning of Dec. 31. The Patriots attacked in two thrusts, commanded by Montgomery and Arnold.

Arnold led the attack against the lower city from the north, but went down early with a bullet in his leg. Morgan took over leadership of this force, and they successfully entered the city following him over the first barricade. When Montgomery fell, his attack faltered, and the British General Carleton led hundreds of local Quebec militia to encircle the second attack. He moved cannons and men to the first barricade, behind Morgan's force. Split up in the lower city, subject to fire from all sides, they were forced to surrender piecemeal. Shortly before surrendering, Morgan surrendered his sword to a local French priest, refusing to give it up before Carleton for a formal surrender, which Morgan viewed as humiliating to him. Morgan was among the 372 men captured. He remained a prisoner of war until exchanged in January 1777.

11th Virginia Regiment

When he rejoined Washington early in 1777, Morgan was surprised to learn that he had been promoted to colonel for his efforts at Quebec. He was assigned to raise and command a new infantry regiment, the 11th Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line.

On June 13, 1777, Morgan was also placed in command of the Provisional Rifle Corps, a light infantry unit of 500 riflemen selected primarily from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia units of the main army. Many were drawn from his own permanent unit, the 11th Virginia Regiment. Washington assigned them to harass General William Howe's rear guard, and Morgan followed and attacked them during their entire withdrawal across New Jersey.

Saratoga

Col. Morgan is shown in white, right of center

Morgan's regiment was reassigned to the army's Northern Department and on Aug. 30 he joined General Horatio Gates to aid in resisting Burgoyne's offense. He is prominently depicted in the painting of the Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga by John Trumbull.[5]

Freeman's Farm

Morgan led his regiment, with the added support of Henry Dearborn's 300-man New Hampshire infantry, as the advance to the main forces. At Freeman's Farm, they ran into the advance of General Simon Fraser's wing of Burgoyne's force. Every officer in the British advance party died in the first exchange, and the advance guard retreated.

Morgan's men charged without orders, but the charge fell apart when they ran into the main column led by General Hamilton. Benedict Arnold arrived, and he and Morgan managed to reform the unit. As the British began to form on the fields at Freeman's farm, Morgan's men continued to break these formations with accurate rifle fire from the woods on the far side of the field. They were joined by another seven regiments from Bemis Heights.

For the rest of the afternoon, American fire held the British in check, but repeated American charges were repelled by British bayonets.

Bemis Heights

Burgoyne's next offensive resulted in the Battle of Bemis Heights on Oct. 7. Morgan was assigned command of the left (or western) flank of the American position. The British plan was to turn that flank, using an advance by 1,500 men. This brought Morgan's brigade once again up against General Fraser's forces.

Passing through the Canadian loyalists, Morgan's Virginia sharpshooters got the British light infantry trapped in a crossfire between themselves and Dearborn's regiment. Although the light infantry broke, General Fraser was trying to rally them, encouraging his men to hold their positions when Benedict Arnold arrived. Arnold spotted him and called to Morgan: "That man on the grey horse is a host unto himself and must be disposed of — direct the attention of some of the sharpshooters amongst your riflemen to him!" Morgan reluctantly ordered Fraser shot by a sniper, and Timothy Murphy obliged him.

With Fraser mortally wounded, the British light infantry fell back into and through the redoubts occupied by Burgoyne's main force. Morgan was one of those who then followed Arnold's lead to turn a counter-attack from the British middle. Burgoyne retired to his starting positions, but about 500 men poorer for the effort. That night, he withdrew to the village of Saratoga (renamed Schuylerville in honor of Philip Schuyler) about eight miles to the northwest.

During the next week, as Burgoyne dug in, Morgan and his men moved to his north. Their ability to cut up any patrols sent in their direction convinced the British that retreat was not possible.

New Jersey and retirement

After Saratoga, Morgan's unit rejoined Washington's main army, near Philadelphia. Throughout 1778 he hit British columns and supply lines in New Jersey, but was not involved in any major battles. He was not involved in the Battle of Monmouth but actively pursued the withdrawing British forces and captured many prisoners and supplies. When the Virginia Line was reorganized on Sept. 14, 1778, Morgan became the colonel of the 7th Virginia Regiment.

Throughout this period, Morgan became increasingly dissatisfied with the army and the Congress. He had never been politically active or cultivated a relationship with the Congress. As a result, he was repeatedly passed over for promotion to brigadier, favor going to men with less combat experience but better political connections. While still a colonel with Washington, he had temporarily commanded Weedon's brigade, and felt himself ready for the position. Besides this frustration, his legs and back aggravated him from the abuse taken during the Quebec Expedition. He was finally allowed to resign on June 30, 1779, and returned home to Winchester.

In June 1780, he was urged to re-enter the service by General Gates, but declined. Gates was taking command in the Southern Department, and Morgan felt that being outranked by so many militia officers would limit his usefulness. After Gates' disaster at the Battle of Camden, Morgan thrust all other considerations aside, and went to join the Southern command at Hillsborough, North Carolina.

The Southern Campaign

He met Gates at Hillsborough, and was given command of the light infantry corps on Oct. 2. At last, on Oct. 13, 1780, Morgan received his promotion to Brigadier General.

Morgan met his new Department Commander, Nathanael Greene, on Dec. 3, 1780 at Charlotte, North Carolina. Greene did not change his command assignment, but did give him new orders. Greene had decided to split his army and annoy the enemy in order to buy time to rebuild his force. He gave Morgan's command of about 700 men the job of foraging and enemy harassment in the backcountry of South Carolina, while avoiding direct battle.[6]

When this strategy became apparent, the British General Cornwallis sent Colonel Banastre Tarleton's British Legion to track him down. Morgan talked with many of the militia who had fought Tarleton before, and decided to disobey his orders, by setting up a direct confrontation.

The Battle of Cowpens

Morgan chose to make his stand at Cowpens, South Carolina. On the morning of Jan. 17, 1781, they met Tarleton in the Battle of Cowpens. Morgan had been joined by militia forces under Andrew Pickens and William Washington's dragoons. Tarleton's legion was supplemented with the light infantry from several regiments of regulars.

Morgan's plan took advantage of Tarleton's tendency for quick action and his disdain for the militia,[7] as well as the longer range and accuracy of his Virginia riflemen. The marksmen were positioned to the front, followed by the militia, with the regulars at the hilltop. The first two units were to withdraw as soon as they were seriously threatened, but after inflicting damage. This would invite a premature charge from the British.

The tactic resulted in a double envelopment. As the British forces approached, the Americans, with their backs turned to the British, reloaded their muskets. When the British got too close, they turned and fired at point-blank range in their faces. In less than an hour, Tarleton's 1,076 men suffered 110 killed and 830 captured. The captives included 200 wounded. Although Tarleton escaped, the Americans captured all his supplies and equipment, including the officers' slaves. Morgan's cunning plan at Cowpens is widely considered to be the tactical masterpiece of the war and one of the most successfully executed double envelopments of all of modern military history.[8]

Cornwallis had lost not only Tarleton's legion, but also his light infantry, which limited his speed of reaction for the rest of the campaign. For his actions, Virginia gave Morgan land and an estate that had been abandoned by a Tory. The damp and chill of the campaign had aggravated his sciatica to the point where he was in constant pain; on February 10, he returned to his Virginia farm.[9] In July 1781, Morgan briefly joined Lafayette to pursue Banastre Tarleton once more, this time in Virginia, but they were unsuccessful.[10]

After the Revolution

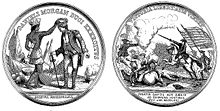

After Morgan returned home to Charles Town, he became gradually less active. He turned his attention to investing in land, rather than clearing it, and eventually built an estate of over 250,000 acres (1,000 km2). As part of his settling down, he joined the Presbyterian Church and built a new house near Winchester, Virginia, in 1782. He named the home Saratoga after his victory in New York. The Congress awarded him a gold medal in 1790 to commemorate his victory at Cowpens.

In 1794 he was briefly recalled to national service to help suppress the Whiskey Rebellion. Serving under General "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, Morgan led one wing of the militia army into western Pennsylvania.[11] The massive show of force brought an end to the protests without a shot being fired. After the uprising had been suppressed, Morgan commanded the remnant of the army that remained in Pennsylvania for a time.[12]

Morgan ran for election to the United States House of Representatives twice, as a Federalist. He lost in 1794, but won next time to serve a term from 1797 to 1799. He died in 1802 at his daughter's home in Winchester on his 66th birthday. Daniel Morgan was buried in Old Stone Presbyterian Church graveyard and moved to the Mt. Hebron Cemetery in Winchester, after the Civil War.

Legacy

Daniel Morgan's great-great-grandfather was also the uncle of the famous Welsh privateer and pirate, Henry Morgan.

In 1821 Virginia named a new county—Morgan County—in his honor. (It is now in West Virginia.) The states of Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, and Tennessee followed their example. The North Carolina city of Morganton is also named after Morgan.

In 1881 (on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the Cowpens battle), a statue of Morgan was placed in the central town square of Spartanburg, South Carolina. The square (Morgan Square) and statue remain today (see photo in Spartanburg article).

In the early 1950s, an attempt was made to remove his body to Cowpens, but the Frederick-Winchester Historical Society blocked the move by securing an injunction in circuit court. The event was pictured by a staged photo that appeared in Life magazine.

In 1973, the home Saratoga was declared a National Historic Landmark.

Morgan and his actions served as one of the key sources for the fictional character of Benjamin Martin in The Patriot, a motion picture released in 2000.

Footnotes

- ^ Higginbotham, Don (1979). Daniel Morgan:. UNC Press Books. p. 11. ISBN 0807813869, 9780807813867.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Higginbotham p.13-15

- ^ McCullough, David. 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005) p. 38

- ^ Peckham, Howard H. The War for Independence: A Military History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958) p. 30

- ^ "Key to the Surrender of General Burgoyne". Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ^ Golway, Terry. Wasgington's General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2005) p. 241

- ^ Golway, p. 248

- ^ Golway, pp. 245-248

- ^ Golway, p. 248

- ^ Peckham, p. 167

- ^ Higginbotham, pp. 189–91.

- ^ Higginbotham, pp. 193–98.

Further reading

- Bodie, Idella. The Old Waggoner (Juvenile nonfiction). Sandlapper Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-87844-165-4

- Calahan, North. Daniel Morgan: Ranger of the Revolution. AMS Press, 1961; ISBN 0-404-09017-6

- Graham, James The Life of General Daniel Morgan of the Virginia Line of the Army of the United States: with portions of his correspondence. Zebrowski Historical Publishing, 1859; ISBN 1-880484-06-4

- Higginbotham, Don. Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman. University of North Carolina Press, 1961. ISBN 0-8078-1386-9

External links

- 1736 births

- 1802 deaths

- American Presbyterians

- American Revolutionary War prisoners of war

- American people of Welsh descent

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Continental Army generals

- Continental Army officers from Virginia

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Virginia

- People from Winchester, Virginia

- People of Virginia in the French and Indian War

- Virginia colonial people

- Virginia Federalists