Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh | |

|---|---|

Eitaro Ogawa (left) working with sculptor Do Ho Suh (right). | |

| Born | 1962 |

| Nationality | South Korean |

| Education | Seoul National University Rhode Island School of Design Yale University |

| Known for | Sculpture, Installation art |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 서도호 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Seo Doho |

| McCune–Reischauer | Sŏ Toho |

Do Ho Suh (Korean: 서도호, Hanja: 徐道濩, b. 1962 in Seoul, South Korea) is a Korean artist who works primarily in sculpture, installation, and drawing. Suh is well known for re-creating architectural structures and objects using fabric in what the artist describes as an "act of memorialization."[2] After earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts from Seoul National University in Korean Painting, Suh began experimenting with sculpture and installation while studying at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). He graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting from RISD in 1994, and went on to Yale where he graduated with a Master of Fine Arts in sculpture in 1997. He practiced for over a decade in New York before moving to London in 2010. Suh regularly shows his work around the world, including Venice where he represented Korea at the 49th Venice Biennale in 2001. In 2017, Suh was the recipient of the Ho-Am Prize in the Arts. Suh currently lives and works in London.

Suh's work focuses on the different ways architecture mediates the experience of space. Architecture has been a key reference for the artist since the mid-1990s—even for pieces like Floor (1997-2000) that do not resemble buildings. As a result, Suh pays particular attention to the site-specificity of the work, and sensorial experience of the viewer engaging with his pieces while moving in the exhibition space. A number of his sculptures produced in the past few decades consider the possibilities for sculpture to become architecture, and vice-versa.[3]: 147 His blurring of the line between sculpture and architecture often renders architectural structures portable through material change, as exemplified by one of his most famous works Seoul Home...(1999), for which he recreated his childhood home using polyester and silk. Suh's use of fabric and paper functioning like a "second skin" make it possible for his pieces to be folded up and transported.[4]: 29 His material choices of rice paper, and fabric commonly found in hanbok also refer to traditional Korean art and architecture.

Early life[edit]

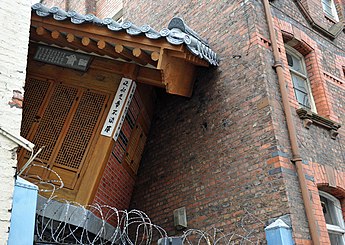

Suh was born in Seoul to Se-ok Suh, a famous Korean ink painter, and Min-Za Chung, one of the founders of Arumjigi-Culture Keepers (재단법인 아름지기), a non-profit organization supporting the preservation of Korean tradition and heritage. Their family home was composed of five contemporary and traditional structures. Se-ok Suh modeled one building after the main quarters and library of a civilian-style home King Sunjo built in 1878 in the palace garden, and Suh constructed their home using red-pine sourced from the palace complex when many of the palace buildings were dismantled. Suh's version was later used as a model for the redecoration of the original palace home.[5]: 29

Education[edit]

After failing to get the necessary grades to study marine biology, Suh applied to Seoul National University (SNU) to study Oriental painting.[6] He graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in 1985 and Master of Fine Arts in 1987 from SNU, and completed the mandatory military service in South Korea before moving to the US to study at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 1991.

Suh applied to RISD, which was the only American art school that accepted him, in order to move to the US with his first wife, a Korean American graduate student. Suh felt a sense of relief in the US: moving away from Korea allowed the artist to build his career outside of his father's shadow.[6]

Although Suh had completed both his undergraduate and graduate studies in Korea, RISD had the artist enroll as a sophomore. Suh attributes his turn to sculpture to artist Jay Coogan, whose course on figuration Suh took when he first started at RISD. This led Suh to create sculptures in the corridors of the school. His artistic interventions focused on these overlooked spaces and drew out their relationship with the people who regularly traverse them.[7]: 27 Suh also took courses on pattern-making at the RISD that allowed him to develop the foundational skills he needed to work with fabric. He graduated from RISD with a BFA in 1994.

Suh continued studying sculpture at Yale University, and graduated with an MFA in 1997. While at Yale, Suh met Rirkrit Tiravanija. Tiravanija later helped launch Suh's career in New York.[8]: 34

Work[edit]

Hallway (1993)[edit]

Upon arriving in the US, Suh began measuring spaces in the many new surroundings he went through, and experimenting with altering them. For this temporary installation at RISD, Suh added a laminated birch panel to the floor of a hallway, and a long curved rod that passerby had to walk through in order to get down the hallway.

High School Uni-Face: Boy (1995), High School Uni-Face: Girl (1997)[edit]

Suh overlapped images of students from high school yearbooks to create the two computer-generated color photographs. Suh again turned to this reference to Korean high school for his 1996 installation High School Uni-Forms that show sixty school uniforms connected together, and later in 2000 for Who Am We?

Seoul Home... (1999)[edit]

The Korean Cultural Center in Los Angeles commissioned Suh to create the installation, leading him to begin exploring the question of home through his work. Suh came up with the idea while he was living in New York in the 90s reminiscing about his childhood home. In 1994 he produced a smaller-scale piece—Room 515/516-I/516-II—using muslin in order to see if it was possible to create a large-scale fabric house. He was able to realize the full project in 1999.

The installation features a 1:1 replica of Suh's childhood home in Korea, including both the main structure and fixtures like toilets, radiators, and kitchen appliances. The entire installation is made of polyester fabric and silk held up with thin metal rods.

Spatial traces[edit]

Every time the piece is transported, he adds the name of the city to the title (e.g. Seoul Home/L.A. Home in 1999 for the first exhibition). For Suh, this continual renaming allows the work to hold the traces of each space it traverses, and thus reshape the viewer's notion of what a home is. The movement of the work also allows Suh to carry his childhood memories with him no matter where he goes, therefore making it possible for him to shrink the distance between where he came from and is at the present.[5]: 33

Passageways[edit]

Passageways play a crucial role in Suh's installation in not only connecting different sections, but also, according to Suh, engaging with the exhibition space as a whole. For the installation at the Korean Cultural Center, Suh thought about the center as a space of cultural displacement that transports objects from Korea's past to the present-day US, and creates physical and conceptual passageways between those two spaces and points in time.[5]: 31

Suh plans to connect all of his fabric pieces, including Seoul Home..., under the title The Perfect Home so that a visitor can enter through one door, and travel through replicas of all of Suh's past residences without leaving. Suh has begun to utilize computer modeling software in producing some of these pieces.

Traditional Korean art and architecture[edit]

Suh links his work with what he describes as the porosity of Korean architecture, exemplified by the doors and windows that exist in lieu of walls, and translucent rice paper that covers them. Suh also chose fabric for his installation thinking about the function of rice paper in traditional Asian painting.[5]: 35

Suh's mother was key in finding traditional Korean seamstresses who assisted Suh in making his work. But while he describes his work as "clothing for space," and thus drawing from the vocabulary of Korean costumes, such as magenta thread for stitching, Suh does claim that in the end his work veers closer to industrial design and architecture than to fashion.[5]: 37

Suh has also written about Joseon Dynasty artist Kim Jeong-hui's 1844 painting Landscape in Winter, both expressing admiration for the work showing a small house, and connecting it to Suh's own desire to create the perfect home.[9]: 161

Floor (1997-2000)[edit]

Suh again explored the possibility of transforming the structure of the exhibition space with Floor. The site-specific installation raised the floor of the gallery, inviting viewers to walk on the forty glass panels supported by 180,000 cast plastic human figures. The work was featured in the 2001 Venice Biennale.

Who Am We? (2000)[edit]

The installation features high-school yearbook photos from Korea from over three decades of graduating classes juxtaposed together, and printed on sheets of paper pasted to the wall.

Both Floor and Who Am We? are examples of works that curators and critics have described in terms of the individual/collective dichotomy. While Suh does acknowledge that his pieces do engage with the concept, he foregrounds their role in shaping a viewer's experience of space, and considers the tendency of ascribe individuality to the West and collectivity to the East to be reductive.[10]: 274

Paratrooper (2003-ongoing)[edit]

Suh's Paratrooper works feature an elliptical piece of fabric embroidered with the names of people who are connected to Suh in some way. The threads used for the names extends beyond the fabric, and are gathered together in the hand of a sculpture of a paratrooper elevated on a platform. Suh has described the work as being able to function as anyone's self-portrait as the installation shows how the point at which all relationships meet is where the individual comes into being.[10]: 275 Suh has also cited the multiple valences of the Korean word inyeon as a central idea at play for the work.[10]: 277

Paratrooper was the first work Suh made and showed in Korea. After showing the work in Korea, and then the US, Suh noted the difference in reception for the work. He found that Korean audiences had an emotional response to the work while American audiences read the piece as a commentary on the military.[10]: 277

"Speculation Project" (2006-ongoing)[edit]

Speculation Project is a thirteen-part work narrating Suh's journey from Korea to the US. The first chapter, Fallen Star: Wind of Destiny (2006), is composed of styrofoam and resin. The piece commissioned by Artspace in San Antonio, shows a miniature Korean house atop a white tornado. The next chapter, Fallen Star: A New Beginning (1/35th Scale) (2006) reveals that the house has crashed into the Providence building Suh lived in during his RISD days. Fallen Star: Epilogue (1/8th Scale) (2006) features the same collision, but with new brick and scaffolding.

Suh has emphasized the whimsicality of many of the works in the series for both him and the viewer. The project has allowed Suh to revisit his childhood love for toys and model-making.[11]

Fallen Star 1/5 (2008)[edit]

The work both references a specific film (The Wizard of Oz), and explores the relationship between the viewer and cinematic space with a 1:5 scale model of Suh's childhood in Korea colliding with a similarly sized replica of his Providence apartment.[12]: 20 The impact bifurcates the Providence house, splitting not only the building, but also all of its contents, right down the middle. In contrast, the Korean hanok has only a Singer sewing table and parachute fabric and string inside.

Fallen Star (2012)[edit]

The installation features a blue cottage suspended at an angle on the top of the Jacobs School of Engineering on the La Jolla campus of the University of California, San Diego. In front of the cottage is a garden and path to the front of the house. Those who enter will find the angle of the floor and house are mismatched, and the interior is furnished with pictures of families, including Suh's, on the wall, as well as an array of knickknacks typically found inside a home. When discussing the work, Suh has connected the instability of the structure with his own sense of disorientation when he first arrived in the US.[13]: 71

"Rubbing/Loving Project" (2012-2016)[edit]

Suh rubbed crushed colored pastel over paper placed on every surface of his New York apartment. He finished the project in 2016 after his landlord had passed away with the aim of showing the palimpsest of traces that had accrued over time with each occupant.[13]: 71

Suh has emphasized the physicality and sensuality of the act of rubbing that transforms one's interpretation of a space.[6]

The Company Housing of Gwangju Theater (2012)[edit]

Suh worked with his team to produce a rubbing of the interior of a local theater troupe's former house while blindfolded, relying on only touch to create the piece. The work was one of several rubbings Suh did for the Gwangju Biennale that year. Suh has cited the influence of Jacques Derrida's Memoirs of the Blind for the installation. He has also connected the blindfolds to Korean media censorship in the 70s and 80s of protests and demonstrations like the Gwangju Uprising.[14]: 31 Blindness as a visual motif and concept also appears in works like Karma (2010).

Thread drawings (2011-ongoing)[edit]

Instead of using ink, watercolor, or graphite as he does in his sketchbooks, Suh has created a series of drawings that utilize thread embedded in paper. He began developing his technique in 2011 during his residency at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI). Early experiments involved directly sewing wet paper, as well as sewing thin tissue paper and dissolving the tissue paper before transferring the drawing to thicker paper. After a number of failed attempts to make larger-scale works, an intern at the Institute suggested that Suh use gelatine paper. Suh began sewing the gelatine paper, attaching the paper to paper pulp that dissolves the gelatine paper, and rubbing the thread in order to bind it to the thicker paper fibers. Suh has described the pleasure of ceding total control over the work due the contingency of the threading with the sewing machine, and paper shrinkage.[11]

Inverted Monument (2022)[edit]

While the sculpture seems to be composed of red thread from afar, the piece showing a human figure suspended upside-down inside a pedestal is actually made from red plastic. Suh worked with a robotics team at Bristol's Centre for Print Research to produce the sculpture.

Critical reception[edit]

Biography and global itinerancy[edit]

Critics and curators writing about Suh's work often draw connections between his installations and personal background as part of the Korean diaspora. Phoebe Hoban, for example, describes Fallen Star (2012) as "a powerfully poetic expression of his cultural experience."[15] They tend to link his own experiences moving across the world with broader issues of displacement and immigration, thus opening up the work to a less-culturally specific interpretation—exemplified by critic Frances Richard's description of Suh's Seoul Home as "a scrim onto which anybody may project his or her reveries about any absent home."[16] Curator Rochelle Steiner contextualizes Suh's work within a broader trend in contemporary art during the 90s tackling issues of transportability and itinerancy, and connects Suh's sculptures to earlier precedents for this trend like Marcel Duchamp's La boîte-en-valise (1936–41).[17]: 14

However, art historians Miwon Kwon and Joan Kee have critiqued the narrowness of this interpretation of Suh's practice, complicating the readings of his work that view them as representative of a global itinerancy.

Miwon Kwon outlines a doubleness that characterizes much of Suh's works. His installations both expand and contract the field of vision for the viewer, thus allowing the work to contain both minimalist and anti-minimalist qualities. Pieces like High School Uni-Form (1996) and Floor (1997-2000) image the multitude while registering their historical passing. Reproductions of his homes are indexical products that are specific to particular sites, while also asserting their own autonomy moving from space to space. Kwon also considers the dualism present in writing on Suh's work as seeing his culturally specific installations incorporating Korean architectural styles, fabric, and ornamental details as culturally unspecific. She argues that these critics view the culturally specific aspects as secondary, and paradoxically utilize them in order to find the commonality of itinerancy. Therefore, they view him as a "retooled nomadic subject of globalization" whose work is valued not for "its authenticity as a product of another culture but its capacity to register through that authenticity another authenticity of itinerancy and cultural displacement."[18]: 23

Joan Kee argues that Suh's work gestures to the unknowability of the home, making his installations recreating his previous residences perpetually materially and conceptually unresolved. While critics and curators often connect pieces like Seoul Home... (1999) to Suh's biography, Kee points out that the installations also display a glaring lack of personal mark with general features that could be found in any urban home. Suh's work thus becomes open to multiple readings dependent on the viewer's engagement with the work, and as such, resists any singular line of interpretation that views his pieces as emblems of globalization.[19]

Engagement with architecture[edit]

Architect and critic Julian Rose also resists viewing the structures in Suh's installations as inherent signs, and instead highlights the subtle ways in which Suh engages with architectural issues through his work. Rose argues that Suh's use of different materials both pulls his re-creations away from indexicality, and draws them towards the fundamental issues of representation and space in the field of architecture. Rose asserts that Suh's work acts as a reminder that architecture is not inherently symbolic, but rather gains its meaning through human interaction.[20]

Affective qualities[edit]

Art historian Ayla Lepine focuses on the affective properties of Suh's work that reveal the limits of the encounter with a piece that produces a sense of anxiety due to its reference to a space that "inspires but does not and could not contain the work." The inhabitability of Suh's buildings gesture to the distance and reflective meaning of the installations in relation to their original referents.[21]: 142

Relationship to spectacle[edit]

Curator and critic Chung Shinyoung identifies the antimodernist devices of literariness and theatricality in Suh's Speculation Project, but questions if there is anything more to the work to justify its dramatization of allegorical fiction beyond spectacle and the artist's indulgence.[22]

Personal life[edit]

Suh moved to London in 2010 for his second wife, Rebecca Boyle Suh. The artist and British arts educator have two children.[6]

Select exhibitions[edit]

Solo exhibitions[edit]

2001[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh: Some/One," Whitney Museum of American Art at Philip Morris, New York

2002[edit]

- "The Perfect Home," Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City

- "Do Ho Suh," Serpentine, London

2005[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh," The Fabric Workshop, Philadelphia

- "Do Ho Suh," Maison Hermes, Tokyo; Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Washington, D.C.

2007[edit]

- "Cause & Effect," Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York

2010[edit]

- "A Perfect Home: The Bridge Project," Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York

2012[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh: Perfect Home," 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

2013[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh: Home within Home within Home within Home within Home," National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul

2018[edit]

- "One: Do Ho Suh," Brooklyn Museum, New York

- "Do Ho Suh," Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar

2019[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh," Victoria & Albert Museum, London

- "Do Ho Suh: 348 West 22nd Street," Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

2022[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh," Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney

Group exhibitions[edit]

2000[edit]

- "Greater New York," P.S.1, New York

2001[edit]

- "Uniform, Order and Disorder," P.S.1, New York

- "Plateau of Humankind," 49th Venice Biennale, Venice

2003[edit]

- 8th International Istanbul Biennial

2006[edit]

- "Facing East: Portraits from Asia," Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- "New Works: 06.2," Artspace, San Antonio

- "Siting: Installation Art 1969-2002," Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

2008[edit]

- "Peppermint Candy: Contemporary Korean Art," Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Santiago

- "Psycho Buildings: Artists and Architecture," Hayward Gallery, London

2012[edit]

- 9th Gwangju Biennale

2018[edit]

- "Do Ho Suh: Robin Hood Gardens: A Ruin in Reverse," 16th Venice Biennale of Architecture, Venice

Collections[edit]

Suh's work can be found in major museum collections worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, N.Y.; Minneapolis Institute of Art; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Seattle Asian Art Museum, Seattle, WA; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Tate Modern, London; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo; the Towada Art Center, Aomori; and the Museum of World Culture, Gothenburg.

Selected works include:

- Hub-2, Breakfast Corner, 260-7 (2018)

- Hub-1, Entrance, 260-7 (2018)

- New York City Apartment (2015)

- Fallen Star (2012)

- 348 West 22nd Street (2011-2015)

- Net-Work (2010)

- Karma (2010)

- Home within Home (2009-2011)

- Fallen Star 1/5 (2008-2011)

- Cause & Effect (2012)

- Paratrooper-II (2005)

- Paratrooper-V (2005)

- Unsung Founders (2005)

- Some/One (2005)

- Reflection (2004)

- Karma Juggler (2004)

- Staircase-IV (2004)

- Screen (2003)

- Doormat: Welcome Back (2003)

- The Perfect Home (2002)

- Public Figures (1998)

- Who Am We? (2000)

- Floor (1997-2000)

- High School Uni-form (1997)

Awards[edit]

- Ho-Am Prize in the Arts (2017)

Further reading[edit]

- Morsiani, Paula, ed. Subject Plural: Crowds in Contemporary Art, exh. cat. Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 2001.

- Do Ho Suh, exh. cat. Seoul: Artsonje Center, 2003.

- Standing on a Bridge, exh. cat. Seoul: Arario, 2004.

- A Contingent Object of Research: The Perfect Home: The Bridge Project, exh. cat. New York: Storefront for Art and Architecture, 2010.

- Kim, Miki Wick. Korean Contemporary Art. Munich: Prestel, 2012.

- Do Ho Suh. "Do-Ho Suh: The Poetics of Space." Interview by Jayoon Choi. ArtAsia Pacific (May 1, 2012), 88–89.

- Harris, Jennifer, ed. Art_Textiles, exh. cat. Manchester: The Whitworth, The University of Manchester, 2015.

- Do Ho Suh: Works on Paper at STPI, exh. cat. Milan: DelMonico Books, 2021.

- Do Ho Suh: Portal, exh. cat. Milan: DelMonico Books, 2022.

External links[edit]

- Lehmann Maupin Gallery

- Victoria Miro Gallery

- Art:21 -- Art in the Twenty-First Century

- TateShots: Do Ho Suh - Staircase-III The artist talks about his installation piece. 25 March 2011.

- 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art Kanazawa

- Profile overview on Artsy

References[edit]

- ^ "LA미술관, 서도호 작품 매입 전시", Chosun Ilbo, 2006-05-03, archived from the original on 2013-01-19, retrieved 2012-06-15

- ^ Do Ho Suh, quoted in Lucy Ives, "Do Ho Suh's Translucent Architectures," Frieze 229 (September 21, 2022), https://www.frieze.com/article/do-ho-suh-translucent-architectures.

- ^ Miwon Kwon, "Do Ho Suh," in Psycho Buildings: Artists Take on Architecture, exh. cat. (London: Hayward Publishing, 2008), 146-148.

- ^ Sarah Suzuki, "Essay," in Do Ho Suh, exh. cat. (Wassenaar: Voorlinden, 2019), 27-31.

- ^ a b c d e Do Ho Suh, "The Perfect Home: A Conversation with Do-Ho Suh," interview by Lisa G. Corrin, in Do-Ho Suh, exh. cat. (Seattle: Seattle Museum of Art, 2002), 27-39.

- ^ a b c d Belcove, Julie L. (2013-11-07). "Artist Do Ho Suh Explores the Meaning of Home". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ Lisa G. Corrin, "The Perfect Home: A Conversation with Do-Ho Suh," in Do-Ho Suh, exh. cat. (Seattle: Seattle Museum of Art, 2002), 27-39.

- ^ Lynn Zelevansky, "Contemporary Art from Korea: The Presence of Absence," in Your Bright Future: 12 Contemporary Artists from Korea, exh. cat. (Houston; Los Angeles: The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2009), 30-49.

- ^ Do Ho Suh, "Do Ho Suh on Kim Jeong-hui," in In My View: Personal Reflections on Art by Today's Leading Artists (London: Thames & Hudson, 2012), 160-161.

- ^ a b c d Do Ho Suh, "Social Structures and Shared Autobiographies: Do-Ho Suh," interview by Tom Csaszar, Conversations on Sculpture (New Jersey: International Sculpture Center, 2007), 272-279.

- ^ a b Do Ho Suh, "Do Ho Suh: Threads to Liberty," interview by Gillian Daniel, Elephant 24 (January 29, 2017), https://elephant.art/ho-suh-threads-liberty/.

- ^ Ralph Rugoff, "Psycho Buildings," Psycho Buildings: Artists Take on Architecture, exh. cat. (London: Hayward Publishing, 2008): 17-26.

- ^ a b "Do Ho Suh," in When Home Won't Let You Stay: Migration through Contemporary Art, exh. cat. (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, 2019), 70-71.

- ^ Do Ho Suh, conversation with Clara Kim, March 7, 2014, cited in Clara Kim, "Rubbing is Loving: Do Ho Suh's Archeology of Memory," in Do Ho Suh: Drawings, exh. cat. (Munich: DelMonico, 2014), 27-32.

- ^ Phoebe Hoban, "Do Ho Suh," Art in America, November 3, 2011, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/aia-reviews/do-ho-suh-2-61037/.

- ^ Frances Richard, "Home in the World: The Art of Do-Ho Suh," Artforum 40, no. 5 (January 2002), 115.

- ^ Rochelle Steiner, "Do Ho Suh's Karmic Journey," Do Ho Suh: Drawings, exh. cat. (Munich: DelMonico Books, 2014), 7-17.

- ^ Miwon Kwon, "The Other Otherness: The Art of Do-Ho Suh," in Do-Ho Suh, exh. cat. (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 2002), 9-23.

- ^ Joan Kee, “Evanescent Terrain: The Unknowable Home in the Works of Do-Ho Suh.” In Home and away, exh. cat. Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2003.

- ^ Julian Rose, "Do Ho Suh: The Contemporary Austin," Artforum 53, no. 6 (February 2015), 239.

- ^ Ayla Lepine, "Installation as Encounter," in Contemplations of the Spiritual in Art (Bern: Peter Lang, 2013), 131-149.

- ^ Chung Shinyoung, "Do-Ho Suh: Gallery Sun Contemporary," Artforum 45, no. 6 (February 2007), 312.