Donald Woods

Donald Woods | |

|---|---|

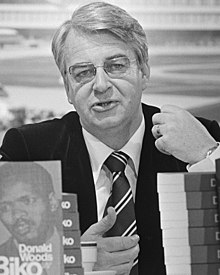

Woods in 1978 | |

| Born | Donald James Woods 15 December 1933 |

| Died | 19 August 2001 (aged 67) London, England |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouse | Wendy Woods |

Donald James Woods CBE (15 December 1933 – 19 August 2001) was a South African journalist and anti-apartheid activist. As editor of the Daily Dispatch, he was known for befriending fellow activist Steve Biko, who was killed by police after being detained by the South African government. Woods continued his campaign against apartheid in London, and in 1978 became the first private citizen to address the United Nations Security Council.[1]

Early life

[edit]Woods was born at Hobeni, Cape Province, where his family had lived for five generations. His ancestors arrived in South Africa with the 1820 Settlers. Woods was born and raised in what has since become the Eastern Cape province, as were both of his parents, all four of his grandparents, all eight of his great grandparents and all sixteen of his great, great grandparents. All thirty-two of his great great great grandparents emigrated to the Cape Colony from England.[2] His parents ran a trading post in Transkei, a tribal reserve, which the South African government would later designate a bantustan. As a boy Woods had extensive regular contact with the Xhosa people. He spoke fluent Xhosa and Afrikaans, as well as his mother tongue, English.

Woods and his brother, Harland, were sent to the Christian Brothers College in Kimberley in the predominantly Afrikaner Northern Cape for their secondary education. The school was academically rigorous, and the Irish Christian Brothers had a reputation for neutrality on questions of politics. While Woods was away at school, the National Party came to power in 1948 and began to build the apartheid structure. When he started his law course at the University of Cape Town in 1952, Woods supported government policies that separated the races, but was wary of the heavy hand of the Afrikaner National Party. During his legal studies he started to question the separatist views he grew up with, becoming politically active in the Federal Party, which rejected apartheid and drew its support from liberal English-speaking whites.

Woods spent two years as a legal apprentice, with the goal of becoming a barrister, but gravitated toward journalism. Just as he was about to embark on his career as a journalist, the 23-year-old Woods was approached by the Federal Party to run for a seat in parliament. His campaign was unsuccessful, and he went back to his job as a cub reporter for the Daily Dispatch newspaper in East London. For two years during the late 1950s, he honed his skills as a journalist by writing and sub-editing for various newspapers in England and Wales. It was while working in Wales that he developed a love and respect for the Welsh people that endured all his life. While working on the Western Mail in Cardiff, Woods became friends with colleague Glyn Williams, who later joined him on the Daily Dispatch and eventually became editor himself. Before returning to South Africa, Woods served as a correspondent for London's now defunct Daily Herald, travelling throughout the eastern and southern United States, eventually arriving in Little Rock, Arkansas, where he filed stories comparing U.S. segregation with South Africa's apartheid.

Woods went back to work at the Dispatch and married Wendy Bruce, whom he had known since they were teenagers in their hometown. They had six children: Jane, Dillon, Duncan, Gavin, Lindsay, and Mary. Their fourth son, Lindsay, born in 1970, contracted meningitis and died just before his first birthday. The family had settled into a comfortable life in East London, and in February 1965, at the age of 31, Woods rose to the position of editor-in-chief of the Daily Dispatch,[3] which held an anti-apartheid editorial policy. As editor, Woods expanded the readership of the Dispatch to include Afrikaans-speakers as well as black readers in nearby Transkei and Ciskei. Woods integrated the editorial staff and flouted apartheid policies by seating black, white, and coloured reporters in the same work area. He favoured hiring reporters who had had experience working overseas. Woods had several scrapes with the South African Security Police regarding editorial matters and on numerous occasions ruffled the feathers of Prime Minister B. J. Vorster in frank, face-to-face exchanges regarding the content of Dispatch editorials. Woods found himself tiptoeing around, and sometimes directly challenging, the increasingly restrictive government policies enacted to control the South African press.

Relationship with Steve Biko

[edit]Under Woods, the Daily Dispatch was very critical of the South African government, but was also initially critical of the emerging Black Consciousness Movement under the leadership of Steve Biko. Mamphela Ramphele, Biko’s partner, berated Woods for writing misleading stories about the movement, challenging him to meet with Biko.

The two men became friends, leading the Security Police to monitor Woods's movements. Nevertheless, Woods continued to provide political support to Biko, both through writing editorials in his newspaper and controversially hiring black journalists to the Daily Dispatch.

On 16 June 1976, an uprising broke out in Soweto, in which predominantly 13- to 16-year-old students from Soweto participated in a march to protest against being taught in Afrikaans and against the Bantu Education system in general. The police ordered the children to disperse, and when they refused, the police opened fire, killing scores (and by some estimates, hundreds)[4] of them, as the children pelted the police with stones. The government responded by banning the entire Black Consciousness Movement along with many other political organisations, as well as issuing banning orders against various people. Donald Woods was one of them and was effectively placed under house arrest.[5][6]

Returning to his home on the evening of 18 August 1977, from a trip to Cape Town, Biko was arrested, imprisoned and mortally beaten. He was killed on 12 September. Woods went to the morgue with Biko's wife, Ntsiki Mashalaba, and photographed Biko's battered body. The photographs were later published in Woods's book, exposing the South African government's cover-up of the cause of Biko's death.

Life in exile

[edit]

Soon after Biko's death, Woods was himself placed under a five-year ban. He was stripped of his editorship, and was not allowed to speak publicly, write, travel or work for the duration of his ban. Over the next year, he was subjected to increasing harassment, and his phone was tapped. His six-year-old daughter was severely burned by a T-shirt laced with ninhydrin.[1] Convinced that the government was trying to have him killed, Woods decided to flee South Africa.[7]

Woods and friends Drew Court and Robin Walker devised a plan for him to be smuggled out of his house. Disguised as a Roman Catholic priest, Father "Teddy Molyneaux", on 30 December 1977,[8] Woods hitchhiked out of town then drove in convoy with Court 480 kilometres (300 mi) before attempting to cross the Telle River, a tributary of the Orange River, between South Africa and Lesotho. Following days of steady rain, the river had flooded, leaving him to resort to crossing at the Telle Bridge border crossing in a Lesotho Postal Service truck driven by an unsuspecting Mosotho man, who was merely giving the "priest" a lift.

He made it undetected by South African customs and border officials to Lesotho, where, prompted by a prearranged telephone call, his family joined him shortly afterwards. Once they arrived in Lesotho, Bruce Haigh, a diplomat of the Australian Embassy in South Africa, drove him to Maseru. With the help of the British High Commission (in Maseru) and from the Government of Lesotho, they flew under United Nations passports and with one Lesotho Government official over South African airspace, via Botswana to London where they were granted political asylum.[9]

After arriving in London, Woods became an active spokesman against apartheid. Acting upon the advice of Oliver Tambo, the President of the African National Congress (ANC), Woods became a passionate advocate of nations imposing sanctions against South Africa. He toured the United States campaigning for sanctions against apartheid. The trip included a three-hour session, arranged by President Jimmy Carter, to address officials in the U.S. Department of State. Woods also spoke at a session of the United Nations Security Council in 1978.

On 11 February 1990, Nelson Mandela was released from prison after serving twenty-seven years, 17 of those years on Robben Island. That Easter, Mandela came to London to attend a concert at Wembley Stadium to thank the anti-apartheid Movement and the British people for their years of campaigning against apartheid. Woods gave Mandela a tie in the black, green and gold colours of the African National Congress to celebrate the event, which Mandela wore at the concert the next day.

Return to South Africa

[edit]Woods returned to South Africa in 1994 to support the fundraising efforts for the ANC election fund. His son Dillon was one of the organizers of the fundraising appeal in the United Kingdom. On 27 April 1994, Woods went to vote at the City Hall in Johannesburg. A cheering crowd took him to the head of the queue, giving him the place of honour so that he could be one of the first to vote in the new South Africa. Following the election, Woods worked for the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism in Johannesburg.

On 9 September 1997, on the twentieth anniversary of the death of Steve Biko, Woods was present in East London when a statue of Biko was unveiled by Nelson Mandela and the bridge across the Buffalo River was renamed the "Biko Bridge". Woods also gave his support to the Action for Southern Africa event in Islington, London honouring Biko, helping to secure messages from Ntsiki Biko, Mamphela Ramphele (then the Vice Chancellor of the University of Cape Town) and Mandela.

Cry Freedom

[edit]Director Richard Attenborough filmed the story of Woods and Steve Biko, based upon the books which Woods had written, under the title Cry Freedom. Donald and Wendy Woods became involved in the project, working closely with the actors and crew. The film was shot largely on location in Zimbabwe (South Africa still being under apartheid at the time). It was released in 1987 to critical acclaim, and won several awards. Woods was portrayed by Kevin Kline, who became friends with Woods and his wife and family during the filming. The friendship continued until Woods' death in 2001. Wendy Woods was played by Penelope Wilton. Biko was played by Denzel Washington, who was Oscar-nominated for the role. At nearly three hours long, the film also featured appearances by John Thaw, Timothy West, Julian Glover, Ian Richardson and Zakes Mokae.

It closes with a list of deaths of black activists in police custody in South Africa, with the official explanations of cause of death.

Final years

[edit]In the last year of his life, Woods gave his name to support an appeal to erect a statue of Nelson Mandela in Trafalgar Square outside the South African High Commission, where anti-apartheid campaigners had demonstrated during the period of the apartheid regime.

Woods was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2000. He died of cancer on 19 August 2001 in London.[10][11][12]

The 3-metre (9 ft) high bronze statue of Mandela was eventually erected on nearby Parliament Square, Westminster City Council. It was unveiled by the British Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, on 29 August 2007, in the presence of Woods' widow, Wendy, Nelson Mandela and his wife Graça Machel, and Richard Attenborough.

Wendy died in 2013 from melanoma.[13]

Donald Woods's eldest son Dillon Woods is currently the Chief Executive of the East London-based Donald Woods Foundation, which is an educational foundation in South Africa.[14] His son Gavin appears on the Johnny Vaughan show on Radio X.[15]

Awards

[edit]- Conscience-in-Media Award, from the American Society of Journalists and Authors, in 1978

- World Association of Newspapers' Golden Pen of Freedom Award, in 1978

Memorials

[edit]- Donald Woods Gardens – A street in Tolworth, Surrey

- Donald Woods Foundation – An NGO assisting the South African National Department of Health in the management and treatment of HIV/AIDS in rural populations.

Works

[edit]- Asking for Trouble: The Autobiography of a Banned Journalist. Atheneum. 1981. ISBN 978-0-689-11159-4.

- South African Dispatches: Letters to My Countrymen. Penguin. 1987. ISBN 978-0-14-010080-8.

- Biko. Paddington Press. 1978. ISBN 978-0-8050-1899-8., later edition published by Henry Holt, New York, 1987

- Filming with Attenborough

- Rainbow Nation Revisited: South Africa's Decade of Democracy. André Deutsch. 2000. ISBN 978-0-233-99830-5.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Richard, Aldrich (2006). Lessons from history of education : the selected works of Richard Aldrich. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415358910. OCLC 58600047.

- ^ Asking for Trouble: Autobiography of a Banned Journalist by Donald Woods: Peter Smith, 1991

- ^ Williams, Glyn. "The History of the Daily Dispatch". dispatchlive.co.za. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Tuttle, K. (2010). "Soweto, South Africa". In Henry Louis Gates, Jr.; Kwame Anthony Appiah (eds.). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195337709.

- ^ 16 June 1976 Student Uprising in Soweto Archived 1 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. africanhistory.about.com

- ^ Harrison, David (1983). The White Tribe of Africa. University of California Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-520-05066-2.

- ^ "1978: Newspaper editor flees South Africa". On This Day: 1 January, BBC.

- ^ "Banned Editor Flees S. Africa", Los Angeles Times, January 1, 1978, p.I-1 ("The editor left his hometown Friday and arrived in Maseru 300 miles away, Saturday morning.")

- ^ Blandy, Fran (31 December 2007). "SA editor's escape from apartheid, 30 years on". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ Uys, Stanley (20 August 2001). "Obituary: Donald Woods". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ "Donald Woods (obituary)". The Daily Telegraph. 20 August 2001. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ "Donald Woods, who cried for freedom, died on August 19th, aged 67". The Economist. 23 August 2001. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ Hain, Peter (22 May 2013). "Wendy Woods obituary". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Who We Are". Donald Woods Foundation. 10 December 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015.

- ^ Johnny Vaughan on Radio X: 20171128

External links

[edit]- Donald James Woods – South African History Online

- Donald Woods at IMDb

- Donald Woods 4 April 1988 speech at George Washington University on C-SPAN (@ 12 minutes)

- 1933 births

- 2001 deaths

- Deaths from cancer in England

- South African Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- South African emigrants to the United Kingdom

- South African newspaper editors

- South African people of British descent

- South African Roman Catholics

- Steve Biko affair

- University of Cape Town alumni

- White South African anti-apartheid activists

- South African anti-apartheid activists

- Writers from Cape Town

- 20th-century South African journalists

- 21st-century South African journalists