Douglas X-3 Stiletto

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

| X-3 Stiletto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Experimental |

| Manufacturer | Douglas |

| Designer | Schuyler Kleinhans, Baily Oswald and Francis Clauser [1] |

| First flight | 15 October 1952 |

| Retired | 23 May 1956 |

| Status | Preserved at National Museum of the United States Air Force |

| Primary users | United States Air Force NACA |

| Number built | 1 |

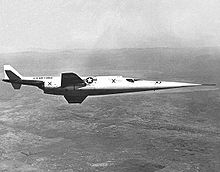

The Douglas X-3 Stiletto was a 1950s United States experimental jet aircraft with a slender fuselage and a long tapered nose, manufactured by the Douglas Aircraft Company. Its primary mission was to investigate the design features of an aircraft suitable for sustained supersonic speeds, which included the first use of titanium in major airframe components. Douglas designed the X-3 with the goal of a maximum speed of approximately 2,000 m.p.h,[2] but it was, however, seriously underpowered for this purpose and could not even exceed Mach 1 in level flight.[3] Although the research aircraft was a disappointment, Lockheed designers used data from the X-3 tests for the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter which used a similar trapezoidal wing design in a successful Mach number 2 fighter.

Design and development

The Douglas X-3 Stiletto was the sleekest of the early experimental aircraft, but its research accomplishments were not those originally planned. It was originally intended for advanced Mach 2 turbojet propulsion testing, but it fell largely into the category of configuration explorers, as its performance (due to inadequate engines) never met its original performance goals.[4] The goal of the aircraft was ambitious — it was to take off from the ground under its own power, climb to high altitude, maintain a sustained cruise speed of Mach 2, then land under its own power. The aircraft was also to test the feasibility of low-aspect-ratio wings, and the large-scale use of titanium in aircraft structures. The design of the Douglas X-3 Stiletto is the subject of U.S. Design Patent #172,588 granted on July 13, 1954 to Frank N. Fleming and Harold T. Luskin and assigned to the Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc.

Construction of a pair of X-3s was approved on 30 June 1949. During development, the X-3's planned Westinghouse J46 engines were unable to meet the thrust, size and weight requirements, so lower-thrust Westinghouse J34 turbojets were substituted, producing only 4,900 lbf (21.8 kN) of thrust with afterburner rather than the planned 7,000 lbf (31.3 kN). The first aircraft was completed and delivered to Edwards Air Force Base, California, on 11 September 1952.

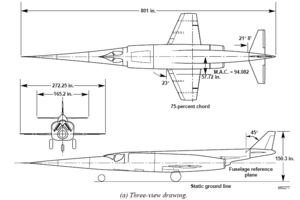

The X-3 featured an unusual slender, streamlined shape having a very long, gently-tapered nose and small trapezoidal wings. The aim was to create the thinnest and most slender shape possible in order to achieve low drag at supersonic speeds. The extended nose was to allow for the provision of test equipment while the semi-buried cockpit and windscreen were designed to alleviate the effects of "thermal thicket" conditions. The low aspect ratio, unswept wings were designed for high speed and later the Lockheed design team used data from the X-3 tests for the similar F-104 Starfighter wing design. Due to both engine and airframe problems, the partially completed second aircraft was cancelled, and its components were used for spare parts.[5]

Operational history

The first X-3 "hop" was made on 15 October 1952, by Douglas test pilot William Bridgeman. During a high-speed taxi test, Bridgeman lifted the X-3 off the ground and flew it about 1 mi (1.6 km) before settling back onto the lakebed. The official first flight was made by Bridgeman on 20 October, and lasted about 20 minutes. He made a total of 26 flights (counting the hop) by the end of the Douglas tests in December 1953. These showed that the X-3 was severely underpowered and difficult to control. Its takeoff speed was an unusually high 260 kts (482 km/h). More seriously, the X-3 did not approach its planned top speed. Its first supersonic flight required that the airplane make a 15° dive to reach Mach 1.1. The X-3's fastest flight, made on 28 July 1953, reached Mach 1.208 in a 30° dive.[3] A plan to re-engine the X-3 with rocket motors was considered but eventually dropped.[5]

With the completion of the contractor test program in December 1953, the X-3 was delivered to the United States Air Force. The poor performance of the X-3 meant only an abbreviated program would be made, to gain experience with low aspect ratio wings. Lieutenant Colonel Frank Everest and Major Chuck Yeager each made three flights. Although flown by Air Force pilots, these were counted as NACA flights. With the last flight by Yeager in July 1954, NACA made plans for a limited series of research flights with the X-3. The initial flights looked at longitudinal stability and control, wing and tail loads, and pressure distribution.

NACA pilot Joseph A. Walker made his pilot checkout flight in the X-3 on 23 August 1954, then conducted eight research flights in September and October. By late October, the research program was expanded to include lateral and directional stability tests. In these tests, the X-3 was abruptly rolled at transonic and supersonic speeds, with the rudder kept centered. Despite its shortcomings, the X-3 was ideal for these tests. The mass of its engines, fuel and structure was concentrated in its long, narrow fuselage, while its wings were short and stubby. As a result, the X-3 was "loaded" along its fuselage, rather than its wings. This was typical of the fighter aircraft then in development or testing.

These tests would lead to the X-3's most significant flight, and the near-loss of the aircraft. On 27 October 1954, Walker made an abrupt left roll at Mach 0.92 and an altitude of 30,000 ft (9,144 m). The X-3 rolled as expected, but also pitched up 20° and yawed 16°. The aircraft gyrated for five seconds before Walker was able to get it back under control. He then set up for the next test point. Walker put the X-3 into a dive, accelerating to Mach 1.154 at 32,356 ft (9,862 m), where he made an abrupt left roll. The aircraft pitched down and recorded an acceleration of -6.7 g (-66 m/s²), then pitched upwards to +7 g (69 m/s²). At the same time, the X-3 side-slipped, resulting in a loading of 2 g (20 m/s²). Walker managed to bring the X-3 under control and successfully landed.

The post-flight examination showed that the fuselage had been subjected to its maximum load limit. Had the acceleration been higher, the aircraft could have broken up. Walker and the X-3 had experienced "roll inertia coupling," in which a maneuver in one axis will cause an uncommanded maneuver in one or two others. At the same time, several North American F-100 Super Sabres were involved in similar incidents. A research program was started by NACA to understand the problem and find solutions.

For the X-3, the roll coupling flight was the high point of its history. The aircraft was grounded for nearly a year after the flight, and never again explored its roll stability and control boundaries. Walker made another ten flights between 20 September 1955 and the last on 23 May 1956. The aircraft was subsequently retired to the U.S. Air Force Museum.[6] Although the X-3 never met its intention of providing aerodynamic data in Mach 2 cruise, its short service was of value. It showed the dangers of roll inertia coupling, and provided early flight test data on the phenomenon. Its small, highly loaded unswept wing was used in the Lockheed F-104 Starfighter,[7] and it was one of the first aircraft to use titanium. Finally, the X-3's very high takeoff and landing speeds required improvements in tire technology.

Production

Two aircraft were ordered, but only one was built. It made 51 flights.

Survivors

- The sole X-3 was transferred in 1956 to the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.[8] As of 2008[update] it is on display in the Museum's Research & Development Gallery.[3]

Specifications (X-3)

General characteristics

- Crew: one

Performance

- Thrust/weight: 0.40

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- Notes

- ^ http://www.scribd.com/doc/45985597/Adventures-in-Research-a-History-of-Ames-Research-Center-1940-1965

- ^ "2000 m.p.h. Goal For Stiletto." Popular Mechanics, January 1954, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Winchester 2005, p. 88.

- ^ Hallion, Richard P. "The NACA, NASA, and the Supersonic-Hypersonic Frontier." NASA Technical Reports. Retrieved: 7 September 2011.

- ^ a b Winchester 2005, p. 89.

- ^ "Factsheet: X-3." National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 12 January 2012.

- ^ Pace 1991, p. 130.

- ^ United States Air Force Museum Guidebook 1975, p. 88.

- Bibliography

- Pace, Steve. X-Fighters: USAF Experimental and Prototype Fighters, XP-59 to YF-23. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1991. ISBN 0-87938-540-5.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Association, 1975 edition.

- Winchester, Jim. "Douglas X-3." Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft. Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2005. ISBN 978-1-84013-809-2.