Earth's magnetic field: Difference between revisions

m Reverting possible vandalism by 81.141.135.71 to version by 218.186.8.253. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (532786) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Magnetic fields extend infinitely, though they are weaker further from their source. The Earth's magnetic field, which effectively extends several tens of thousands of [[kilometre]]s into [[outer space|space]], is called the [[magnetosphere]]. |

Magnetic fields extend infinitely, though they are weaker further from their source. The Earth's magnetic field, which effectively extends several tens of thousands of [[kilometre]]s into [[outer space|space]], is called the [[magnetosphere]]. |

||

==Magnetic poles== |

==Magnetic poles== POO :D |

||

[[Image:Animati3.gif|thumb|left|400px|Simulation of the interaction between Earth's magnetic field and the interplanetary magnetic field.]] |

[[Image:Animati3.gif|thumb|left|400px|Simulation of the interaction between Earth's magnetic field and the interplanetary magnetic field.]] |

||

{{main|North Magnetic Pole|South Magnetic Pole}} |

{{main|North Magnetic Pole|South Magnetic Pole}} |

||

Revision as of 11:51, 25 January 2010

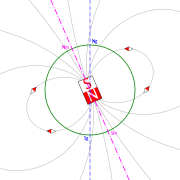

Earth's magnetic field (and the surface magnetic field) is approximately a magnetic dipole, with the magnetic field S pole near the Earth's geographic north pole (see Magnetic North Pole) and the other magnetic field N pole near the Earth's geographic south pole (see Magnetic South Pole). The cause of the field can be explained by dynamo theory. Magnetic fields extend infinitely, though they are weaker further from their source. The Earth's magnetic field, which effectively extends several tens of thousands of kilometres into space, is called the magnetosphere.

==Magnetic poles== POO :D

Two different types of magnetic poles must be distinguished. There are the "magnetic poles" and the "geomagnetic poles". The magnetic poles are the two positions on the Earth's surface where the magnetic field is entirely vertical. Another way of saying this is that the inclination of the Earth's field is 90° at the North Magnetic Pole and -90° at the South Magnetic Pole. At either the South or North Magnetic Poles, a typical compass that is allowed to swing only in the horizontal plane will point in random directions. The Earth's field is closely approximated by the field of a dipole positioned near the centre of the Earth. A dipole defines an axis. The two positions where the axis of the dipole that best fits the Earth's field intersect the Earth's surface are called the North and South geomagnetic poles. If the Earth's field were perfectly dipolar, the geomagnetic and magnetic poles would coincide. However, there are significant non-dipolar terms which cause the position of the two types of poles to be in different places.

The locations of the magnetic poles are not static; they wander as much as 15 km every year (Dr. David P. Stern, emeritus Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA [citation needed]). The pole position is usually not that which is indicated on many charts. The Geomagnetic Pole positions are usually not close to the position that commercial cartographers place "Magnetic Poles." "Geomagnetic Dipole Poles", "IGRF Model Dip Poles", and "Magnetic Dip Poles" are variously used to denote the magnetic poles.[1] The Earth's field changes in strength and position. The two poles wander independently of each other and are not at directly opposite positions on the globe. Currently the magnetic south pole is farther from the geographic south pole than the magnetic north pole is from the geographic north pole.

| North Magnetic Pole[2] | (2001) 81°18′N 110°48′W / 81.3°N 110.8°W | (2004 est) 82°18′N 113°24′W / 82.3°N 113.4°W | (2005 est) 82°42′N 114°24′W / 82.7°N 114.4°W |

| South Magnetic Pole[3] | (1998) 64°36′S 138°30′E / 64.6°S 138.5°E | (2004 est) 63°30′S 138°00′E / 63.5°S 138.0°E | (2005 est)63°06′S 137°30′E / 63.1°S 137.5°E |

Field characteristics

The strength of the field at the Earth's surface ranges from less than 30 microteslas (0.3 gauss) in an area including most of South America and South Africa to over 60 microteslas (0.6 gauss) around the magnetic poles in northern Canada and south of Australia, and in part of Siberia.

The field is similar to that of a bar magnet. The Earth's magnetic field is mostly caused by electric currents in the liquid outer core. The Earth's core is hotter than 1043 K, the Curie point temperature above which the orientations of spins within iron become randomized. Such randomization causes the substance to lose its magnetization.

Convection of molten iron within the outer liquid core, along with a Coriolis effect caused by the overall planetary rotation, tends to organize these "electric currents" in rolls aligned along the north-south polar axis. When conducting fluid flows across an existing magnetic field, electric currents are induced, which in turn creates another magnetic field. When this magnetic field reinforces the original magnetic field, a dynamo is created which sustains itself. This is called the Dynamo Theory and it explains how the Earth's magnetic field is sustained.

Another feature that distinguishes the Earth magnetically from a bar magnet is its magnetosphere. At large distances from the planet, this dominates the surface magnetic field. Electric currents induced in the ionosphere also generate magnetic fields. Such a field is always generated near where the atmosphere is closest to the Sun, causing daily alterations which can deflect surface magnetic fields by as much as one degree. Typical daily variations of field strength are about 25 nanoteslas (nT) (i.e. ~ 1:2,000), with variations over a few seconds of typically around 1 nT (i.e. ~ 1:50,000).[4]

Magnetic field variations

The currents in the core of the Earth that create its magnetic field started up at least 3,450 million years ago.[5]

Magnetometers detect minute deviations in the Earth's magnetic field caused by iron artifacts, kilns, some types of stone structures, and even ditches and middens in archaeological geophysics. Using magnetic instruments adapted from airborne magnetic anomaly detectors developed during World War II to detect submarines, the magnetic variations across the ocean floor have been mapped. The basalt — the iron-rich, volcanic rock making up the ocean floor — contains a strongly magnetic mineral (magnetite) and can locally distort compass readings. The distortion was recognized by Icelandic mariners as early as the late 18th century. More important, because the presence of magnetite gives the basalt measurable magnetic properties, these magnetic variations have provided another means to study the deep ocean floor. When newly formed rock cools, such magnetic materials record the Earth's magnetic field.

Frequently, the Earth's magnetosphere is hit by solar flares causing geomagnetic storms, provoking displays of aurorae. The short-term instability of the magnetic field is measured with the K-index.

Recently, leaks have been detected in the magnetic field, which interact with the Sun's solar wind in a manner opposite to the original hypothesis. During solar storms, this could result in large-scale blackouts and disruptions in artificial satellites.[6]

- See also Magnetic anomaly, South Atlantic Anomaly

Magnetic field reversals

Based upon the study of lava flows of basalt throughout the world, it has been proposed that the Earth's magnetic field reverses at intervals, ranging from tens of thousands to many millions of years, with an average interval of approximately 300,000 years.[7] However, the last such event, called the Brunhes-Matuyama reversal, is theorized to have occurred some 780,000 years ago.

There is no clear theory as to how the geomagnetic reversals might have occurred. Some scientists have produced models for the core of the Earth wherein the magnetic field is only quasi-stable and the poles can spontaneously migrate from one orientation to the other over the course of a few hundred to a few thousand years. Other scientists propose that the geodynamo first turns itself off, either spontaneously or through some external action like a comet impact, and then restarts itself with the magnetic "North" pole pointing either North or South. External events are not likely to be routine causes of magnetic field reversals due to the lack of a correlation between the age of impact craters and the timing of reversals. Regardless of the cause, when magnetic "North" reappears in the opposite direction this is a reversal, whereas turning off and returning in the same direction is called a geomagnetic excursion.

Studies of lava flows on Steens Mountain, Oregon, indicate that the magnetic field could have shifted at a rate of up to 6 degrees per day at some time in Earth's history, which significantly challenges the popular understanding of how the Earth's magnetic field works.[8]

Paleomagnetic studies such as these typically consist of measurements of the remnant magnetization of igneous rock, very often found on the ocean floor. Although deposits of igneous rock are mostly paramagnetic, they do contain traces of ferri- and antiferromagnetic materials in the form of ferrous oxides, thus giving them the ability to possess remnant magnetization. In fact, this characteristic is quite common in numerous other types of rocks and sediments found throughout the world. One of the most common of these oxides found in natural rock deposits is magnetite.

As an example of how this property of igneous rocks allows us to determine that the Earth's field has reversed in the past, consider measurements of magnetism across ocean ridges. Before magma exits the mantle through a fissure, it is at an extremely high temperature, above the Curie temperature of any ferrous oxide that it may contain. The lava begins to cool and solidify once it enters the ocean, allowing these ferrous oxides to eventually regain their magnetic properties, specifically, the ability to hold a remnant magnetization. Assuming that the only magnetic field present at these locations is that associated with the Earth itself, this solidified rock will become magnetized in the direction of the geomagnetic field. Although the strength of the field is rather weak and the iron content of typical rock samples is small, the relatively small remnant magnetization of the samples is well within the resolution of modern magnetometers. The age and magnetization of solidified lava samples can then be measured to determine the orientation of the geomagnetic field during ancient eras.

Magnetic field detection

The Earth's magnetic field strength was measured by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1835 and has been repeatedly measured since then, showing a relative decay of about 10% over the last 150 years [9] The Magsat satellite and later satellites have used 3-axis vector magnetometers to probe the 3-D structure of the Earth's magnetic field. The later Ørsted satellite allowed a comparison indicating a dynamic geodynamo in action that appears to be giving rise to an alternate pole under the Atlantic Ocean west of S. Africa.[10]

Governments sometimes operate units which specialise in the measurement of the Earth's magnetic field. These are geomagnetic observatories, typically part of a national Geological Survey, for example the British Geological Survey's Eskdalemuir Observatory. Such observatories can measure and forecast magnetic conditions which can sometimes affect communications, electric power and other human activities; see magnetic storm.

The military can take a keen interest in determining the characteristics of the local geomagnetic field, in order to detect anomalies in the natural background, which might be caused by the presence of a significant metallic object such as a submerged submarine. Typically, these magnetic anomaly detectors are flown in aircraft like the UK's Nimrod or towed as an instrument or an array of instruments from surface ships.

Commercially, geophysical prospecting companies also use magnetic detectors to identify naturally occurring anomalies from ore bodies, such as the Kursk Magnetic Anomaly.

Animals including birds and turtles can detect the Earth's magnetic field, and use the field to navigate during migration.[11] Cows align their bodies north-south in response to the magnetic field; this response is confused by the magnetic fields surrounding high voltage power lines.[12][13]

Seismo-electromagnetics is an area of research aimed at earthquake prediction.

See also

Global evolution/anomaly of the Earth's magnetic field: [1] sweeps are in 10 degree steps at 10 years intervals. based on data from:The Institute of Geophysics, ETH Zurich

Notes

- ^ "Problem with the "MAGNETIC" Pole Locations on Global Charts". Eos Vol. 77, No. 36, American Geophysical Union, 1996.

- ^ Geomagnetism, North Magnetic Pole. Natural Resources Canada, 2005-03-13.

- ^ South Magnetic Pole. Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Antarctic Division, 2002.

- ^ Nature, Vol 439 (16 Feb 2006)

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1029/2009GC002496, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1029/2009GC002496instead. - ^ Thompson, Andrea (December 16, 2008). "Leaks Found in Earth's Protective Magnetic Shield". Space.com. Imaginova Corp. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ Phillips, Tony (December 29, 2003). "Earth's Inconstant Magnetic Field". Science@Nasa. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

- ^ Coe, R. S.; Prévot, M.; Camps, P. (20 April 2002). "New evidence for extraordinarily rapid change of the geomagnetic field during a reversal". Nature. 374: 687. doi:10.1038/374687a0.

- ^ Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Science, 1988 16 p.435 "Time Variations of the Earth's Magnetic Field: From Daily to Secular" by Vincent Courtillot and Jean Louis Le Mouel

- ^ Hulot G, Eymin C, Langlais B, Mandea M, Olsen N (2002). "Small-scale structure of the geodynamo inferred from Oersted and Magsat satellite data". Nature. 416 (6881): 620–3. doi:10.1038/416620a. PMID 11948347.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Deutschlander M, Phillips J, Borland S (1999) "The case for light-dependent magnetic orientation in animals" Journal of Experimental Biology 202(8): 891-908

- ^ Burda, H; Begall, S; Cerveny, J; Neef, J; Nemec, P (2009). "Extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields disrupt magnetic alignment of ruminants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (14): 5708–13. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811194106. PMC 2667019. PMID 19299504.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dyson, PJ (2009). "Biology: Electric cows". Nature. 458 (7237): 389. doi:10.1038/458389a. PMID 19325587.

References

- Herndon JM (1996-01-23). "Substructure of the inner core of the Earth". PNAS. 93 (2): 646–648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hollenbach DF, Herndon JM (2001-09-25). "Deep-Earth reactor: Nuclear fission, helium, and the geomagnetic field". PNAS. 98 (20): 11085. doi:10.1073/pnas.201393998.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Further reading

- Neil F. Comins (2001). Discovering the Essential Universe

- J.N. Towle (1984). "The Anomalous Geomagnetic Variation Field and Geoelectric Structure Associated with the Mesa Butte Fault System, Arizona". In: Geological Society of America, Bulletin, 95:221, 1984.

- US Dept of Energy (1999). Temperature of the Earth's core

- James R. Wait (1954). "On the relation between telluric currents and the earth’s magnetic field", In: Geophysics, 19, 281-289.

- Martin Walt (1994). Introduction to Geomagnetically Trapped Radiation by

External links

- USGS Geomagnetism Program. Real time monitoring of the Earth's magnetic field. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, February 17, 2005.

- Geomagnetism. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. Apr-2009.

- BGS Geomagnetism. Information on monitoring and modelling the geomagnetic field. British Geological Survey, August 2005.

- William J. Broad, "Will Compasses Point South?". New York Times, July 13, 2004.

- John Roach, "Why Does Earth's Magnetic Field Flip?". National Geographic, September 27, 2004.

- "Magnetic Storm". PBS NOVA, 2003. (ed. about pole reversals)

- "When North Goes South". Projects in Scientific Computing, 1996.

- "3D Earth Magnetic Field Charged-Particle Simulator" Tool dedicated to the 3d simulation of charged particles in the magnetosphere.. [VRML Plug-in Required]

- Stern, David P. (2005-07-08). "Exploration of the Earth's Magnetosphere". NASA. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- http://blackandwhiteprogram.com/interview/dr-dan-lathrop-the-study-of-the-earths-magnetic-field - Interview with Dr. Dan Lathrop, Geophysicist at the University of Maryland, about his experiments with the Earth's core and magnetic field. 7 - 3 - 2008