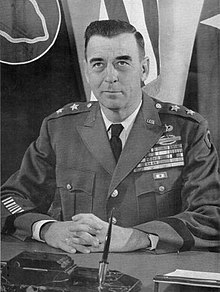

Edwin Walker

Edwin Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Edwin Anderson Walker |

| Born | November 10, 1909 Kerr County, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | October 31, 1993 (aged 83) Dallas, Texas, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1931–1961 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles / wars | World War II Korean War Cold War |

| Awards | Silver Star Legion of Merit (2) Bronze Star Medal (2) |

Edwin Anderson Walker (November 10, 1909 – October 31, 1993) — known as Ted Walker — was a United States Army officer who served in World War II and the Korean War. He became known for his staunch conservative political views and was criticized by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower for promoting a personal political stand while in uniform. Walker resigned his commission in 1959, but Eisenhower refused to accept his resignation and gave Walker a new command over the 24th Infantry Division in Augsburg, Germany. Walker again resigned his commission in 1961 after being publicly and formally admonished by the Joint Chiefs of Staff for calling Eleanor Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman "pink" in print (a charge made by a leftist newspaper called the Overseas Weekly and never substantiated)[1] and for violating the Hatch Act by attempting to direct the votes of his troops. President John F. Kennedy accepted his resignation, making Walker the only US general to resign in the 20th century.

In early 1962, Walker ran for governor of Texas and lost in the Democratic primary election to the eventual winner, John Connally. In October 1962, Walker was arrested for leading riots at the University of Mississippi in protest against admitting a black student, James Meredith, into the all-white university. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy ordered Walker committed to a mental asylum for a 90-day evaluation in response to his role in the Ole Miss riot of 1962, but psychiatrist Thomas Szasz protested and Walker was released in five days. Attorney Robert Morris convinced a Mississippi grand jury not to indict Walker.

Walker was the target of an assassination attempt in his home on April 10, 1963. The assailant, widely suspected to have been Lee Harvey Oswald, fired on the home from outside, but Walker escaped serious injury in the attack when the bullet hit a window frame and fragmented.

Early life and military career

Walker was born in Center Point in Kerr County in the Texas Hill Country. He graduated in 1927 from the New Mexico Military Institute. He attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated in 1931.[2]

Walker's background was as an artilleryman, but during World War II, he commanded a sub-unit of the Canadian-American First Special Service Force. Walker took command of one of the force's three regiments while still in the United States, and commanded the 3rd Regiment throughout its time in Italy. Their first combat actions began in December 1943, and after battling through the Winter Line, the Force was withdrawn for redeployment to the Anzio beachhead in early 1944. After the fight for Rome in June 1944, the force was withdrawn again to prepare for Operation Dragoon. In August 1944, Walker succeeded Robert T. Frederick as the unit's second, and last, commanding officer.[3] The FSSF landed on the Hyeres Islands off of the French Riviera in the autumn of 1944, taking out a strong German garrison. Walker commanded the FSSF when it was disbanded in early 1945.[4]

Walker saw combat in the Korean War, commanding the Third Infantry Division's 7th Infantry Regiment and serving as a senior advisor to the Army of the Republic of Korea.

Next Walker was assigned as commander of the Arkansas Military District in Little Rock, Arkansas. During his years in Arkansas, he implemented an order from President Eisenhower in 1957 to quell civil disturbances during the desegregation of Central High School. Osro Cobb, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas, recalls that Walker

"made it clear from the outset ... that he would do any and everything necessary to see that the black students attended Central High School as ordered by the federal court... he would arrange protection for them and their families, if necessary, and also supervise their transportation to and from the school for their safety."[5]

During that time, Walker repeatedly protested to President Eisenhower that using Federal troops to enforce racial integration was against his conscience. Although Walker obeyed orders and successfully integrated Little Rock High, he also turned toward anti-Communist literature and radio programs. He listened to segregationist preacher Billy James Hargis and oil tycoon H. L. Hunt, whose anti-communist Life Line radio program was the launching platform for conservative activist and publisher Dan Smoot. Anti-Communist activists (in 1957-1959) claimed that Communists controlled key portions of the U.S. government and the United Nations;[citation needed] some Soviet spies and agents occupied prominent positions within the U.S. Federal government, e.g. some of the Silvermaster group.[citation needed]

In 1959, Walker met publisher Robert Welch. The latter man had just founded the John Birch Society to promote his anti-communist views, one of which was that President Eisenhower was a communist. This assertion shocked General Walker, who took it to heart because it coincided with the segregationist position of Reverend Billy James Hargis, that the Civil Rights Movement was a communist plot.

On August 4, 1959, Walker submitted his resignation to the U.S. Army. President Eisenhower denied Walker's request for resignation and offered him command over more than 10,000 troops in Augsburg, Germany, specifically the 24th Infantry Division. Walker accepted that command. He began promoting his "Pro-Blue" indoctrination program for troops, which included a reading list of materials from Billy James Hargis and the John Birch Society.

The name "Pro-Blue," said Walker, was intended to suggest "anti-Red."[6] He later wrote that the Pro-Blue program was based upon his experiences in Korea, where he saw "hastily mobilized and deployed soldiers 'bug out' in the face of Communist units with inferior equipment and often smaller numbers. American soldiers, unprepared for the psychological battlefield, needed to know why they had to beat the enemy as well as the how."[7]

Promoting the Pro-Blue program brought General Walker into conflict with the Overseas Weekly, a tabloid newspaper.[8] On April 16, 1961, the Weekly published an article accusing Walker of effectively brainwashing his troops with John Birch Society materials.[9]

Because the John Birch Society regularly claimed that all U.S. presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt forward had been communists, its positions were considered too politically controversial for a U.S. general to advocate; military officers were not supposed to engage in politics at all. Walker was quoted by the Overseas Weekly as saying that Harry S. Truman, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Secretary of State Dean Acheson were "definitely pink." Additionally, a number of soldiers had complained that Walker was instructing them how to vote in the forthcoming American election by using the Conservative Voting Index, which was biased toward the Republican Party.[10]> According to Walker, his alleged instruction to soldiers as how to vote would later be disproved. The allegation was based on an article in the division newspaper that provided information as to how to fill out absentee ballots.[11]

On the day after the Overseas Weekly story appeared, Walker was relieved of his command by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, while an inquiry was conducted. In October, Walker was reassigned to Hawaii to become assistant chief of staff for training and operations in the Pacific.[citation needed]

Walker chose to resign from the Army a second time. Because the investigation had found no evidence of wrongdoing by Walker, the Secretary of the Army chose to admonish the officer, which could not be appealed by the general. The Secretary also stated that Walker would not be permitted to take command of VIII Corps, as the President had seen fit to withdraw his name for promotion.[12] In protest, Walker, choosing political activism over his 30-year military career, did not retire but resigned his post, thereby forfeiting his pension. This time, President Kennedy accepted his resignation.

Walker said: "It will be my purpose now, as a civilian, to attempt to do what I have found it no longer possible to do in uniform."[13]

Political career

In December 1961, as a civilian, Walker embarked on a career of political speeches along with Hargis. Walker enjoyed enthusiastic crowds all over the United States. His message of anti-communism was popular. He also pressed the McCarthyist belief that communists were inside the United States government. Walker's home base was Dallas, Texas, considered a conservative city [citation needed]. Walker received considerable support from the citizens of Dallas, in particular from oil billionaire, publisher and radio host H. L. Hunt, who supported Walker's first election campaign for governor of Texas.

In February 1962, Walker entered the race, but finished last among six candidates in a Democratic primary election. It was won in a runoff election by John B. Connally, Jr., the choice of Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. Other contenders were the sitting Governor Price Daniel, Highway Commissioner Marshall Formby of Plainview, Attorney General Will Wilson, and Houston lawyer Don Yarborough, the favorite of liberals and organized labor. Due to disfranchisement of minorities in Texas since the turn of the century, the Democratic Party primaries were the only true competitive political contests in the state at that time.[14]

Though Walker had followed orders in achieving desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, he acted privately in organizing protests in September 1962 against the enrollment of James Meredith, an African-American veteran, at the all-white University of Mississippi at Oxford, Mississippi.

On September 26, 1962, Walker went on several radio stations to broadcast this message:

Mississippi: It is time to move. We have talked, listened and been pushed around far too much by the anti-Christ Supreme Court! Rise...to a stand beside Governor Ross Barnett at Jackson, Mississippi! Now is the time to be heard! Thousands strong from every State in the Union! Rally to the cause of freedom! The Battle Cry of the Republic! Barnett yes! Castro no! Bring your flag, your tent and your skillet. It's now or never! The time is when the President of the United States commits or uses any troops, Federal or State, in Mississippi! The last time in such a situation I was on the wrong side. That was in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957-1958. This time -- out of uniform -- I am on the right side! I will be there! [15]

On September 29, 1962, he issued a televised statement:

This is Edwin A. Walker. I am in Mississippi beside Governor Ross Barnett. I call for a national protest against the conspiracy from within. Rally to the cause of freedom in righteous indignation, violent vocal protest, and bitter silence under the flag of Mississippi at the use of Federal troops. This today is a disgrace to the nation in 'dire peril,' a disgrace beyond the capacity of anyone except its enemies. This is the conspiracy of the crucifixion by anti-Christ conspirators of the Supreme Court in their denial of prayer and their betrayal of a nation.[16]

White segregationists from around the state joined students and locals in a violent, 15-hour riot on the campus on September 30, in which two people were killed execution style, hundreds were wounded, and six federal marshals were shot. Walker was arrested on four federal charges, including sedition and insurrection against the United States. He was temporarily held in a mental institution on orders from Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. Kennedy demanded that Walker receive a 90-day psychiatric examination.[17]

The attorney general's decision was challenged by noted psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, who insisted that psychiatry must never become a tool of political rivalry. The American Civil Liberties Union joined Szasz in a protest against the attorney general, completing this coalition of liberal and conservative leaders. The attorney general had to back down, and Walker spent only five days in the asylum.[18]

Walker posted bond and returned home to Dallas, where he was greeted by a crowd of some two hundred supporters.[19] After a federal grand jury adjourned in January 1963 without indicting him, the charges were dropped. Because the dismissal of the charges was without prejudice, the charges could have been reinstated within five years.[20]

Assassination attempt

In February 1963, Walker was joining forces with Billy Hargis in an anti-communist tour called "Operation Midnight Ride".[21] In a speech Walker made on March 5, reported in the Dallas Times Herald, he called on the United States military to "liquidate the [communist] scourge that has descended upon the island of Cuba."[22] Seven days later, Lee Harvey Oswald ordered by mail a Carcano rifle, using the alias "A. Hidell."[23]

According to the Warren Commission, Oswald began to put Walker under surveillance, taking pictures of the general's Dallas home on the weekend of March 9–10.[24] Oswald's friend, 51-year-old Russian émigré and petroleum geologist George de Mohrenschildt,[25] would later tell the Warren Commission that he "knew that Oswald disliked General Walker."[26]

On April 10, 1963, as Walker was sitting at a desk in his dining room, a bullet struck the wooden frame of his dining room window. Walker was injured in the forearm by fragments. Marina Oswald later testified that her husband told her that he traveled by bus to General Walker's house and shot at Walker with his rifle.[27][28] Marina said that Oswald considered Walker to be the leader of a "fascist organization."[29]

Before the Kennedy assassination, the Dallas police had no suspects in the Walker shooting,[30] but Oswald's involvement was suspected within hours of his arrest following the assassination.[31] A note Oswald left for Marina on the night of the attempt, telling her what to do if he did not return, was not found until ten days after the Kennedy assassination.[32][33][34] The bullet was too badly damaged to run conclusive ballistics tests, but neutron activation tests later determined that it was "extremely likely" the bullet was a Carcano bullet manufactured by the Western Cartridge Company, the same ammunition used in the Kennedy assassination.[35]

Police Detective D. E. McElroy commented, "Whoever shot at the general was playing for keeps. The sniper wasn't trying to scare him. He was shooting to kill." Marina Oswald stated later that she had seen Oswald burn most of his plans in the bathtub, though she hid the note he left her in a cookbook, with the intention of bringing it to the police should Oswald again attempt to kill Walker or anyone else. Marina later quoted her husband as saying, "Well, what would you say if somebody got rid of Hitler at the right time? So if you don't know about General Walker, how can you speak up on his behalf?"[36]

Oswald later wrote to Arnold Johnson of the Communist Party USA that on the evening of October 23, 1963, he had attended an "ultra right" meeting headed by Walker.[37]

On November 29, 1963, one week following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, an article appeared in a German newspaper, Die Deutsche Soldaten-Zeitung that accused reputed JFK assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, of having committed the attack on Walker. Oswald's widow, Marina Oswald was asked about the report during a two-week-long detention for interrogation by federal investigators, and she said she believed the report was true. There is some question among skeptics of the Warren Commission's investigation into the JFK assassination, about how the original report came to light in a German newspaper that had been founded by the CIA as an American propaganda publication,[38] and how a European newspaper with no significant presence in the United States was able to receive information about a rather obscure crime that occurred on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. By the time the connection between Oswald and Walker came to light, however, Lee Harvey Oswald had died while in police custody, so no charges were ever filed in the matter.

The verbal attacks on United Nations Ambassador Adlai Stevenson on October 24, 1963 were traced to plans organized by Edwin Walker and his followers among the John Birch Society, according to the November issue of the Texas Observer. One month later, the black-bordered ad and the "Wanted for Treason: JFK" handbills of November 22, 1963, appeared on the streets of Dallas. They were traced to Edwin Walker and his associate Robert Surrey by the Warren Commission. After President Kennedy's assassination, Walker wrote and spoke publicly about his belief that there were two assassins at the "April Crime" - Oswald and another person that was never found.

Immediately after the Warren Commission released their report in September 1964, Walker described it as a "farcical whitewash".[39] Although he accepted their finding that it was Oswald who shot at him the previous year, Walker claimed that the Commission was attempting to cover-up "some sort of conspiracy" that included a connection between Jack Ruby and Oswald.[40]

Adlai Stevenson

Walker organized a verbal attack in Dallas, Texas, on Adlai Stevenson, US Ambassador to the United Nations, on "UN Day," October 24, 1963. In mid-October 1963, Walker rented the same Dallas Memorial Auditorium in which Stevenson would speak. He advertised his opposing event as "US Day" and he invited members of the John Birch Society, the National Indignation Convention, the Minutemen and other organizations opposed to communism and the United Nations.[citation needed]

On the night before Stevenson's speech, Walker held his "US Day" rally and instructed his audience to "buy all the tickets" they could afford to the Stevenson speech, and to fill the auditorium. Walker instructed his audience to heckle Stevenson, bring Halloween noisemakers, and recite their own speeches in the hallways in order to disrupt Stevenson's speech in any way that they could.[citation needed]

Walker also told his followers to fix a banner to the ceiling, to be unfurled at the appropriate moment. It was to be printed with "US out of UN!," and on the other side, "UN out of US!" Walker did not attend Stevenson's speech, nor did he take credit for the orchestration. The audience was so disruptive that Stevenson quit speaking before finishing his presentation and went quickly out to his limousine. On his way, a protester spat at him and one struck him in the head with her placard. Both were arrested. Walker was not charged, although his role was well known at the time.[41]

Associated Press v. Walker

Angered by negative publicity, Walker began to file libel lawsuits against various media outlets. One suit responded to negative coverage of his role in the riot at the University of Mississippi protesting Meredith's admission. The Associated Press reported that Walker had "led a charge of students against federal marshals" and that he had "assumed command of the crowd."[42] Several newspapers were named in the lawsuit. If Walker and his lawyers were successful, he could have won tens of millions of dollars.

A Texas trial court in 1964 found the statements false and defamatory.[43] By that time, Walker and his lawyers had already won over $3 million in lawsuits.

The Associated Press appealed the decision, as Associated Press v. Walker, all the way to the United States Supreme Court.[44] In 1967, the Supreme Court ruled against Walker, finding that, although the statements may have been false, the Associated Press was not guilty of reckless disregard in their reporting about Walker. The Court, which had previously said that public officials could not recover damages unless they could prove malice, extended this to public figures as well.

Later life

By resigning instead of retiring, Walker was unable to draw an army pension. He made statements at the time to the Dallas Morning News that he had "refused" to take his pension. However, he had made several previous requests for his pension dating back to 1973. The army restored his pension rights in 1982.[45]

Walker, then 66, was arrested on June 23, 1976, for public lewdness in a restroom at a Dallas park. He was accused of fondling and propositioning a male undercover police officer.[46][47][48] He was arrested again in Dallas for public lewdness on March 16, 1977.[49][50] He pleaded no contest to one of the two misdemeanor charges, was given a suspended and a 30-day jail sentence and fined $1,000.[51]

Walker died of lung cancer at his home in Dallas in 1993, one week and three days before his 84th birthday.[52] He was never married and had no children.

Media presentations

- Together with Air Force General Curtis LeMay, Walker was said to have inspired the character of the Air Force General James Mattoon Scott (played by Burt Lancaster) in the film Seven Days in May; Walker is also referred to in the film.[53][54]

- He was said to have inspired the character of General Jack D. Ripper (played by Sterling Hayden) in Stanley Kubrick's anti-war film, Dr. Strangelove.[55]

- Cameron Mitchell portrays Walker as a supporting character in the 1985 film Prince Jack (1985). It includes Walker's perspective in a dramatization of Lee Harvey Oswald's assassination attempt against him at home.

- Oswald's attempted assassination of Walker is part of 11/22/63, a novel by Stephen King, about a time traveler who tries to prevent the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. In 11.22.63, a TV adaptation of King's novel, Walker is portrayed by Gregory North.

- Oswald's assassination attempt on Walker is also part of The Third Bullet, a Bob Lee Swagger novel by Stephen Hunter.

- Walker is a character in The Bettor, an alternate history novel by Tim Parise, where he is described as attempting to stage a coup by seizing control of The Pentagon during anti-communist riots in 1967.[56]

Military awards

| Combat Infantryman Badge with star for Second Award | |

|

Senior Parachutist Badge |

Notes

- ^ Courtney, Kent and Phoebe (1961). The Case of General Edwin A. Walker. New Orleans, LA: Conservative Society of America. p. 41.

- ^ Handbook of Texas: "Center Point, Texas." Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ^ Joyce, Ken Snow Plough and the Jupiter Deception: The Story of the 1st Special Service Force and the 1st Canadian Special Service Battalion, 1942-1945 (Vanwell Publishing Ltd., St. Catharines, ON, 2006) ISBN 1-55125-094-2, p. 118.

- ^ Joyce (2006), Snow Plough and the Jupiter Deception, p. 273.

- ^ Osro Cobb, "Osro Cobb of Arkansas: Memories of Historical Significance," Carol Griffee, ed. (Little Rock, Arkansas: Rose Publishing Company, 1989), p. 238.

- ^ p. 105 Schoenwald, Jonathan M. A Time for Choosing: The Rise of American Conservatism, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ^ Major General Edwin A. Walker, Censorship and Survival (New York, The Bookmailer Inc. 1961) pp. 14, 18.

- ^ Minutaglio, Bill; Davis, Steven L. (2013). Dallas 1963. Twelve. ISBN 978-1-4555-2209-5.

- ^ Sokolsky, George E. (May 16, 1961). "Taking Close Look At Overseas Weekly". The Index-Journal. Greenwood, South Carolina. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ Lemza, John W. (2016). "One. From First Arrivals to Established Network (1946-1967)". American Military Communities in West Germany: Life in the Cold War Badlands, 1945-1990. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9781476664163.

- ^ Major General Edwin A. Walker, Censorship and Survival (New York, The Bookmailer Inc. 1961), p. 59.

- ^ Major General Edwin A. Walker, Censorship and Survival (New York, The Bookmailer Inc. 1961), p. 60.

- ^ "I Must Be Free . . .," Time, November 10, 1961.

- ^ Elections of Texas Governors, 1845–2006 Archived July 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Edwin A. Walker and the Right Wing in Dallas, Chris Cravens, 1993, p. 120.

- ^ "Walker Demands a 'Vocal Protest,'" New York Times, September 30, 1962, p. 69.

- ^ Szasz, Thomas (September 23, 2009). "The Shame of Medicine: The Case of General Edwin Walker". Foundation for Economic Education. Foundation for Economic Education. Retrieved May 8 2017.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ Edwin A. Walker and the Right Wing in Dallas, Chris Cravens, 1993, p. 130.

- ^ "Crowd Welcomes Ex-Gen. Walker's Return to Dallas," Dallas Morning News, October 8, 1962, sec. 1, p. 1.

- ^ The Strange Case of Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker.

- ^ "Hargis Says Walker Will Join in Tour," Dallas Morning News, February 14, 1963, sec. 1, p. 16. "Walker Preparing for Crusade," Dallas Morning News, February 17, 1963, sec. 1, p. 16. "Pickets Protest Talks Given by Hargis, Walker," Dallas Morning News, March 28, 1963, sec. 4, p. 18.

- ^ Dallas Times Herald, March 6, 1963.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 17, p. 635, CE 773, Photograph of a mail order for a rifle in the name "A. Hidell," and the envelope in which the order was sent.

- ^ Construction work seen in one of the photos was determined by the supervisor to have been in that state of completion on March 9–10. Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 22, p. 585, CE 1351, FBI Report, Dallas, Tex., dated May 22, 1964, reflecting investigation concerning photographs of the residence of Maj. Gen. Edwin A. Walker. Archived October 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ George de Mohrenschildt. Staff Report of the House Select Committee on Assassinations, vol. 12, 4, p. 53–54, 1979.

- ^ Testimony of George de Mohrenschildt, Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 9, p. 249.

- ^ Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald, Warren Commission Hearings, volume 1, p. 17.

- ^ "Warren Commission Report". National Archives and Records Administration. p. 187. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ "Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 1, p. 16, Testimony of Mrs. Lee Harvey Oswald.

- ^ "HSCA Final Report: I. Findings - A. Lee Harvey Oswald Fired Three Shots..." (PDF). Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "Officials Recall Sniper Shooting at Walker Home", Dallas Morning News, November 23, 1963, sec. 1, p. 15.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 23, pp. 392–393, CE 1785, Secret Service report dated December 5, 1963, on questioning of Marina Oswald about note Oswald wrote before he attempted to kill General Walker.

- ^ Testimony of Ruth Hyde Paine, Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 9, pp. 393–394.

- ^ "Oswald Notes Reported Left Before Walker Was Shot At", Dallas Morning News, December 31, 1963, sec. 1, p. 6.

- ^ Testimony of Dr. Vincent P. Guinn, HSCA Hearings, vol. I, p. 502.

- ^ Testimony of Marina Oswald Porter, HSCA Hearings, vol. II, p. 232.

- ^ Warren Commission Hearings, vol. 20, p. 271, Undated letter from Lee Harvey Oswald to Arnold S. Johnson, with envelope postmarked November 1, 1963. "Rally Talk Scheduled by Walker," Dallas Morning News, October 23, 1963, sec. 1, p. 7. "Walker Says U.S. Main Battleground," Dallas Morning News, October 24, 1963, sec. 4, p. 1.

- ^ "[https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/KIMMANLY_0027.pdf" Project Status Report ,Central Intelligence Agency, January 1953

- ^ {{cite news |author= |title=Probe Is Whitewash: Walker |url=https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/109123561/ |work=The Courier-Journal |location=Louisville, Kentucky |date=March 31, 1964 |page=3 |access-date=June 11, 2017}

- ^ "Warren Probe Whitewashes Plot: Walker". Chicago Tribune. Vol. 118, no. 272 (Final ed.). UPI. September 28, 1964. Section 1, page 2. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ^ Edwin Walker and the Right Wing in Dallas, 1960-1966, by Chris Cravens, chapter 6 (1993).

- ^ Associated Press v. Walker, 393 S.W.2d 671, 674 (1965).

- ^ "The General v. The Cub", Time, June 26, 1964.

- ^ Associated Press v. Walker, 389 U.S. 28 (1967).

- ^ Warren Weaver, Jr., "Pension Restored for Gen. Walker", The New York Times, July 24, 1983, p. 17.

- ^ "General Walker Faces Sex Charge: Right-Wing Figure Accused in Dallas of Lewdness", United Press International, New York Times, July 9, 1976, p. 84.

- ^ "Catch as Catch Can," Time, July 26, 1976.

- ^ "Trial for Walker Routinely Passed", Dallas Morning News, September 15, 1976, p. D4.

- ^ "Police Arrest Retired General for Lewdness," Dallas Morning News, March 17, 1977, p. B18.

- ^ "General Walker Free on Bond", New York Times, March 18, 1977, p. 8.

- ^ "Judge Convicts, Fines Walker", Dallas Morning News, May 23, 1977, p. A5.

- ^ Pace, Eric (November 2, 1993). "Gen. Edwin Walker, 83, Is Dead; Promoted Rightist Causes in 60's". New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=u6lxbxpbOE0C&pg=PA170

- ^ The Presidents We Imagine: Two Centuries of White House Fictions ..., p. 170.

- ^ America's Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era from Elvis to the Fall of ..., p. 68.

- ^ Parise, Tim (2014). The Bettor. The Maui Company. pp. 404–406, 414–417.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)

External links

- Walker, Edwin A., The Handbook of Texas Online

- Edwin Walker collection on the Internet Archive

- 1909 births

- 1993 deaths

- American anti-communists

- American military personnel of the Korean War

- American military personnel of World War II

- Assassination attempt survivors

- Deaths from cancer in Texas

- Deaths from lung cancer

- John Birch Society

- People associated with the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- People from Kerr County, Texas

- People from Dallas

- Texas Democrats

- United States Army generals

- United States Military Academy alumni

- United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

- Recipients of the Silver Star

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Croix de guerre 1939–1945 (France)

- John Birch Society members