Elginia

| Elginia Temporal range: Changhsingian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

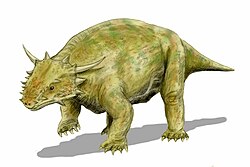

| Restoration of Elginia mirabilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | †Elginia Newton, 1893

|

| Type species | |

| †Elginia mirabilis Newton, 1893

| |

Elginia was a pareiasaur; a member of a group of Late Permian parareptiles which may have grown up to 3 metres (9.8 ft).

Description

Elginia was a dwarf genus of pareiasaur, only about 60 centimetres (2 ft) long, with fossils found at Elgin in Scotland. Elginia is known only from a single skull, which is about 15 cm long, triangular, coarsely sculptured, and armed with a number of paired bosses or spines, with the longest pair growing out of the back of the skull. These spikes were probably used for display rather than physical combat.[1] The upper jaw bears 12 pairs of teeth, each with 9 or 10 cusps. The teeth are slightly constricted at the base and serrated at the crown.

Classification

As with many pareiasaurs, precise phylogenetic placement is uncertain. Elginia shares with Scutosaurus elaborate cranial ornament, which has been used to suggest the two were closely related.[2] Elginia has also been hypothesized to share a relationship with the more basal taxon Dolichopareia (=Nochelesaurus) on the basis of a deeply notched skull table shared with the latter,[3] however other authors have argued that this association was based on taphonomic distortion.[4] Cladistic analyses have tended to nest Elginia deeper among pareiasaurs, making it more derived than the earlier giant Pareiasaurus and Scutosaurus. The placement of Elginia remains volatile, with the taxon hopping between more apical pareiasaurs such as Therischian[4][5] and more basal pareiasaurs such as Scutosaurus and Pumiliopareiasaurs[6]

References

- ^ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 64. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ Boonstra, L.D. 1932. The Phylogenesis of the Pareiasauridae: A Study in Evolution. S. Af. J. Sci. Vol. 29:480–486.

- ^ Walker, A.D. 1973. The Age of the Cuttie’s Hillock Sandstone (Permo-Triassic) of the Elgin Area. Scot. J. Geo. Vol. 9:177–183.

- ^ a b Lee, M.S.Y. 1997. Pareiasaur Phylogeny and the Origin of Turtles. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. Vol. 120:197–280.

- ^ Jalil, N.E., Janvier, P. 2005. Les Pareiasaures (Amniota, Parareptilia) du Permien Supérieur du Bassin d'Argana, Maroc. Geodiversitas. Vol. 27(1):35–132.

- ^ Tsuji, L.A., Müller, J. 2009. Assembling the History of the Parareptilia: Phylogeny, Diversification, and A New Definition of the Clade. Fos. Rec. Vol. 12(1):71–81.

External links

- Elginiidae and Pumiliopareiasauria at Palaeos