Epidemiology of binge drinking

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Binge drinking is more common in men than it is in women.[citation needed] Among students in the USA, approximately 50 percent of men and 39 percent of women binge drink.[citation needed]

Racial differences exist among binge drinking with Hispanics followed by white people having the highest level of binge drinking. Individuals of African descent have a lower level of binge drinking followed by those of Asian descent. In the case of Asians their low level of binge drinking may be due to the presence of the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH2, located on chromosome 12) in many (but by no means the vast majority) that results in poor metabolism of alcohol which leads to severe adverse effects such as facial flushing.[1]

Men are more likely to binge drink (up to 81 percent of alcohol binges are done by men) than women and men are also more likely to develop alcohol dependence than women. People who are homozygous for the ALDH2 gene are less likely to binge drink due to severe adverse effects which occur even with moderate amounts of alcohol consumption.

Asia

Singapore

According to the National Health Survey 2004 conducted by the Health Promotion Board Singapore, binge drinking is defined as consumption of five or more alcoholic drinks over a short period of time.

The survey results showed that the frequency of binge drinking was 15.6% in males, 11.9% higher than that for females (3.7%). The largest proportion of males and females who binge drink fall within the 18 – 29 age group.

In 2007, Asia Pacific Breweries Singapore (APBS) spearheaded Get Your Sexy Back (GYSB), Singapore’s first youth-for-youth initiative to promote responsible and moderate drinking among young adults. The programme seeks to widen awareness and educate individuals about responsible drinking behaviour by raising the social currency of moderation. The programme engages youths in events and activities that are close to their lifestyles, focusing on four major platforms – Music, Fashion, Sports and Friends to spread the message of responsible drinking.

Europe

The drinking age in most countries is either 16 or 18, though in many countries national or regional regulations ban the consumption and/or the sale of alcoholic drinks stronger than beer or wine to those less than 18 years of age. Licensees may sometimes choose to provide beverages such as diluted wine or beer mixed with lemonade (shandy or Lager Top) with a meal to encourage responsible consumption of alcohol. It is generally perceived that binge drinking is most prevalent in the Vodka Belt (most of Northern and some of Eastern Europe) and least common in the southern part of the continent, in Italy, France, Portugal and the Mediterranean (the Wine Belt).[2]

Using a "5-drink, 30-days" (5 standard drinks in a row during the last 30 days) definition, Denmark leads European binge drinking, with 60% of 15–16-year-olds reporting participating in this behavior (and 61% reporting intoxication).[3] However, there currently appears to be at least some convergence of drinking patterns and styles between the northern and southern countries, with the south beginning to drink more like the north more so than the other way around.

Malta

A notable exception to the lower rates of binge drinking in Southern Europe is the Mediterranean island of Malta, which has adopted the British culture of binge drinking, and where teenagers, often still in their early teens, are able to buy alcohol and drink it in the streets of the main club district, Paceville, due to a lack of police enforcement of the legal drinking age of 17.[4] Statistics show that alcohol consumption in Malta exceeds that in the UK (but binge drinking is slightly lower and intoxication is significantly lower),[3] and report that Malta ranks 5th in the world in common binge drinking.[5] Maltese 15–16-year-olds report binge drinking at a rate of 50%, using a 5-drink, 30-day definition, but only 20% report intoxication in the past 30 days.[3]

Spain

Since the mid-1990s the botellón has been growing in popularity among young people. Botellón, which literally means "big bottle" in Spanish, is a drinking party or gathering that involves consuming alcohol, usually spirits (often mixed with soft drinks), in a public or semi-public place (beaches, parks, streets, etc.). This can be considered a case of binge drinking since most people that attend it consume three to five drinks in less than five hours.[citation needed] Among 15–16-year-olds, 23% report being intoxicated in the past 30 days.[3]

Russia

Binge drinking in Russia ("Zapoy" ("Запой") in Russian), often takes the form of two or more days of continuous drunkenness. Sometimes it can even last up to a week. One study found that among men ages 25–54, about 10% had at least one episode of zapoy in the past year, which can be taken as a sign that one has a drinking problem.[6]

Almost half of working-age men in Russia who die are killed by alcohol abuse, reducing Russia's male life expectancy significantly.[6][7][8] Vodka is the preferred alcoholic beverage, and Russia is notably considered part of the Vodka Belt. Using a 5-drink, past 30 days definition, 38% of Russian 15–16-year-olds have binged and 27% became intoxicated, a percentage that is on par with other European countries, and even lower than some.[3]

United Kingdom

In the UK, parallels have been drawn between binge drinking and the Gin Crisis of 18th century England.[9] Some areas of the media are spending a great deal of time reporting on what they see as a social ill that is becoming more prevalent as time passes. In 2003, the cost of binge drinking was estimated as £20 billion a year.[10] In response, the government has introduced measures to deter disorderly behavior and sales of alcohol to people under 18, with special provisions in place during the holiday season. In January 2005, it was reported that one million admissions to UK emergency department units each year are alcohol-related; in many cities, Friday and Saturday nights are by far the busiest periods for ambulance services.

The culture of drinking in the UK is markedly different from that of some other European nations. In mainland Europe, alcohol tends to be consumed more slowly over the course of an evening, often accompanied by a restaurant meal. In Scandinavia, occasional bouts of heavy drinking are the norm. In the UK (as well as Ireland), by contrast, alcohol is commonly consumed in rapid binges, leading to more regular instances of severe intoxication. In this way the British combine Northern European volumes of consumption with frequency resembling that of Southern Europe. This "drinking urgency" may have been inspired by traditional pre-midnight pub closing hours in the UK, whereas bars in continental Europe would typically remain open for the entire night. This may have stemmed from the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, emergency legislation dating back to the first world war regulating pub opening times with the intention of getting workers out of the pub and into the munitions factories. Consequently, it was criticised for being draconian and denying the working classes their pleasures. This is one of the reasons for introducing the Licensing Act 2003 which came into effect in England and Wales in 2005, and which allows 24 hour licensing (although not all bars have taken advantage of the change). Some observers, however, believed it would exacerbate the problem.[11]

As of 2008, results have been mixed and inconsistent across the country.[12] Among young people (under 25), binge drinking (and drinking in general) in England appears to have declined since the late 1990s according to the National Health Service.[13][14]

While being drunk (outside of a student context) in mainland Europe is widely viewed as being socially unacceptable,[15] in the UK the reverse is true in many social circles. Particularly amongst young adults, there is often a certain degree of peer pressure to get drunk during a night out.[16] This culture is increasingly becoming viewed by politicians and the media as a serious problem that ought to be tackled, partly due to health reasons, but mostly due to its association with violence and anti-social behaviour.[17]

Using a 5-drink, 30-days definition, British 15–16-year-olds binge drink at a rate of 54%, the fourth highest in Europe, and 46% report intoxication in the past 30 days.[18]

The British TV channel Granada produces a program called Booze Britain, which documents the binge drinking culture by following groups of young adults.

As a reaction to the binge drinking epidemic in Britain, several charities have been created to raise awareness of the dangers of binge drinking and promote responsible drinking. These charities notably include Alcohol Concern and Drinkaware.

The Americas

Canada

Canadian binge drinking rates are comparable to the United States, and resemble most the geographically similar states that border on it. For example, 29% of 15- to 19-year-olds (35% male, 22% female) and 37% of 20- to 24-year-olds (47% male, 17.9% female) report having 5 or more drinks on one occasion, 12 or more times a year in 2000–01.[19]

In university, binge drinking is especially common during the first week of orientation, commonly known as "frosh week." The first ever known study comparing the drinking patterns of Canadian and American college students under age 25 (in 1998 and 1999, respectively) found that although Canadian students were more likely to drink, American students drank more heavily overall.[20]

"Heavy alcohol use" was defined as usually having 5/4 drinks or more on the days that the person drinks in the past 30 days (American) or 2–3 months (Canadian). Among past year drinkers, 41% and 35% of American and Canadian students, respectively, reported participated in this behavior. Among the total sample, it was 33% and 30%, respectively. Differences included the lack of a gender gap in Canada compared with America, as well some as age-related differences. Canadians exceeded Americans in reported heavy alcohol use until age 19 (especially among the 1% percentage of students under 18), at which point Americans overtook and then began to exceed Canadians, especially among 21- and 22-year-olds. After age 23, there was no longer much of a difference.[20] In Canada, the legal drinking age is 18 or 19, depending on the province.

A relatively popular drinking game among the Canadian skateboarders and heavy metal culture is "wizard sticks", in which drinkers tape a stack of their empty beer cans to the can from which they are currently drinking. The name comes from the fact that when the stack gets tall enough, it resembles a wizard's staff.[21]

United States

Despite having a legal drinking age of 21, binge drinking in the United States remains very prevalent among high school and college students. Using the popular 5/4 definition of "binge drinking", one study found that, in 1999, 44% of American college students (51% male, 40% female) engaged in this practice at least once in the past two weeks.[22]

One can also look at the prevalence of "extreme drinking" as well. A more recent study of US first-semester college freshmen in 2003 found that, while 41% of males and 34% of females "binged" (using the 5/4 threshold) at least once in the past two weeks, 20% of males and 8% of females drank 10/8 or more drinks (double the 5/4 threshold) at least once in the same period, and 8% of males and 2% of females drank at least 15/12 drinks (triple the threshold).[23]

A main concern of binge drinking on college campuses is how the negative consequences of binge drinking affect the students. A study done by the Harvard School of Public Health reported that students who engage in binge drinking experience numerous problems such as: missing class, engaging in unplanned or unsafe sexual activity, being victims of sexual assault, unintentional injuries, and physical ailments.[24] In 2008 the U.S Surgeon General estimated that around 5,000 Americans aged under 21 die each year from alcohol-related injuries involving underage drinking.[25] Rates of binge drinking in women have been increased; high risk drinking puts these women at increased risk of the negative long-term effects of alcohol.[26]

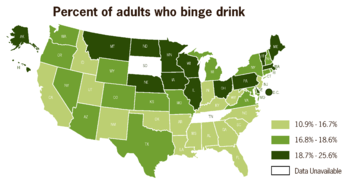

The population of people who binge drink mainly comprises young adults aged 18–29, although it is by no means rare among older adults. For example, in 2007 (using a 5-drinks definition per occasion for both genders), 42% of 18- to 25-year-olds "binged" at least once a month, while 20% of 16–17-year-olds and 19% of those over age 35 did so.[27] The peak age is 21. Prevalence varies widely by region, with the highest rates being in the North Central states.[28]

The annual Monitoring the Future survey found that, in 2007, 10% of 8th graders, 22% of 10th graders, and 26% of 12th graders report having had five or more drinks at least once in the past two weeks.[29] The same survey also found that alcohol was considered somewhat easier to obtain than cigarettes for 8th and 10th graders, even though the minimum age to purchase alcohol is 21 in all 50 states, while for cigarettes it is 18.

The following table represents the percentage of those age 12-20 who illegally binge drink in the United States.[30]

| Asian | Black | Hispanic | American Indian | White |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.9% | 10.4% | 17.2% | 20.3% | 21.4% |

American Indians and First Nations

Binge drinking is a common pattern among Native Americans in both Canada and the United States. Anastasia M. Shkilnyk who conducted an observational study of the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation of Northwestern Ontario in the late 1970s when they were demoralized by Ontario Minamata disease has observed that heavy Native American drinkers may not be physiologically dependent on alcohol, but abuse it by engaging in binge drinking, a practice associated with child neglect, violence, and impoverishment. After binges during which entire families and their friends drink until they are unconscious and their funds are exhausted, they go about their business without drinking.[31][31]

Oceania

Australia

In 2004–2005, statistics from the National Health Survey[32] show that among the general population over 18; 88% of males and 60% of females engaged in binge drinking at least once in the past year, with 12% and 4%, respectively, doing so at least once a week. Among 18- to 24-year-olds, 49% of males and 21% of females did so at least once a week. At the time, the definition for "binge drinking" corresponded to 7 or more standard Australian drinks per occasion for males and 5 or more for females, roughly equivalent to (but slightly less than) the 5/4 (standard American) drinks definition.[32]

In March 2008, the Australian government earmarked A$53 million towards a campaign against binge drinking, citing two studies done in the past eight years which showed that binge drinking in Australia was at what Prime Minister Kevin Rudd called "epidemic levels".[33] On June 15, the Australian Medical Association released new guidelines defining binge drinking as four standard Australian drinks a night.[34]

The last survey of drinking habits by the Australian Bureau of Statistics found there was an increase in drinking outside the home. In 1999, 34 percent of spending on alcoholic drinks took place on licensed premises. By 2004 this figure had risen to 38 percent. This figure is expected to fall in 2008 in Australia because of stricter licensing laws, smoking bans in pubs and the extra premium people have to pay for buying alcohol in a bar.[35]

New Zealand

Concerns over binge drinking by teenagers has led to a review of liquor advertising being announced by the New Zealand government in January 2006. The review considered regulation of sport sponsorship by liquor companies, which at present is commonplace. Previously the drinking age in New Zealand was 20, then dropped to 18 in 1999.[36]

In direct conjunction with the age-lowering, the Police were found to strictly enforce the on-license (bar, restaurant) code for underage-drinking, less so for the off-licences (liquor stores, supermarkets). As a result, young people ages 15–17 found it significantly harder to get into (or be served at) bars and restaurants than it was before with a poorly enforced (though higher) drinking age of 20. This asymmetric enforcement led to a period of many of New Zealand's youth getting strangers to purchase high alcohol content beverages for them (e.g. cheap vodka or rum) at liquor stores.[37]

A propensity to consume an entire bottle of spirits developed and led to an instant increase in the amount of youths under 18 being admitted to A&E hospitals. The price of alcohol at supermarkets and liquor stores had also gone down, and the number of outlets had mushroomed as well.[38] Alcohol remains cheap, and sweet, spirit-based ready to drink beverages (similar to alcopops) remain popular among young people.[39]

An example of this binge drinking mentality, often seen amongst university students, is the popularity of drinking games such as Edward Wineyhands and Scrumpy Hands, similar to the American drinking game Edward Fortyhands. A recent study showed that 37% of undergraduates binged at least once in the past week.[40] The New Zealand health service classifies Binge Drinking as anytime a person consumes 5 or more standard drinks in a sitting.

References

- ^ Courtney, KE.; Polich, J. (Jan 2009). "Binge drinking in young adults: Data, definitions, and determinants". Psychol Bull. 135 (1): 142–56. doi:10.1037/a0014414. PMC 2748736. PMID 19210057.

- ^ "Alcohol Alert Digest". Institute of Alcohol Studies UK. 1997.

- ^ a b c d e http://www.udetc.org/documents/CompareDrinkRate.pdf Youth Drinking Rates and Problems: A Comparison of European Countries and the United States (Sources: 2003 ESPAD Survey and 2003 United States Monitoring the Future Survey)

- ^ "They're closing the tap". Malta Today. No. 323. 15 January 2006. Archived from the original on 2010-01-16.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Piscopo, R.V.; D’Emanuele, A.O. (22 June 2005). "Don't Risk it — sedqa's new binge-drinking campaign". malta INDEPENDENT.

- ^ a b Tomkins S, Saburova L, Kiryanov N, et al. (April 2007). "Prevalence and socio-economic distribution of hazardous patterns of alcohol drinking: study of alcohol consumption in men aged 25–54 years in Izhevsk, Russia". Addiction. 102 (4): 544–53. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01693.x. PMC 1890567. PMID 17362291.

- ^ Nemtsov A (February 2005). "Russia: alcohol yesterday and today". Addiction. 100 (2): 146–9. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00971.x. PMID 15679743.

- ^ Treml, Vladimir G. (October 1982). "Death from Alcohol Poisoning in the USSR". Soviet Studies. 34 (4): 487–505. doi:10.1080/09668138208411441. JSTOR 151904.

- ^ Borsay, Peter (September 2007). "Binge drinking and moral panics: historical parallels??". History & Policy. United Kingdom: History & Policy. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Binge drinking costing billions". BBC. 19 September 2003.

- ^ 24-hour laws haven't cured binge drinking telegraph.co.uk

- ^ Elizabeth Stewart and agencies (4 March 2008). "Government admits 'mixed' results from 24-hour licensing". Guardian. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ^ Bowcott O (26 May 2010). "English drinking less alcohol, official figures show". Guardian.

- ^ "Statistics on Alcohol: England, 2010" (PDF). National Health Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rolling away the barrel". The Economist. 2010-04-08.

- ^ Robertson, Poppy (2008-09-09). "What teenagers think about binge drinking". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Mack, Jon (2009). "The Last Chance Saloon: The Drinking Banning Order". Criminal Law & Justice Weekly. 173 (51/52): 805–7.

- ^ "Youth Drinking Rates and Problems: A Comparison of European Countries and the United States" (PDF). 2005. Archived from the original on 2015-09-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ "Frequency of Drinking". Faslink.org. Archived from the original on 2010-10-29. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b http://alcoholism.about.com/gi/dynamic/offsite.htm?site=http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/cas/Documents/Canadian1%2DpressRelease/ First National Comparison

- ^ "'Wizard Stick' Parties a Binge Drinking concern". Jointogether.org. Archived from the original on 2008-12-25. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wechsler H, et al. "College Binge Drinking in the 1990s: A Continuing Problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study" (PDF).

- ^ White AM, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder H (June 2006). "Many college freshmen drink at levels far beyond the binge threshold". Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 30 (6): 1006–10. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00122.x. PMID 16737459.

- ^ Tewksbury R, Higgins GE, Mustaine EE (2008). "Binge Drinking Among College Athletes and Non-Athletes". Deviant Behavior. 29 (4): 275–293. doi:10.1080/01639620701588040.

- ^ Tomorrow's World - July/August 2008 - "Armageddon And Beyond" - Page 27

- ^ Kelly-Weeder, S. (December 2008). "Binge drinking in college-aged women: framing a gender-specific prevention strategy". J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 20 (12): 577–84. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00357.x. PMID 19120588.

- ^ Kennet, Joel (2008). "3. Alcohol Use". In Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Office of Applied Studies (ed.). Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. NSDUH Series H-34. Rockville MD: Department of Health and Human Services. SMA 08-4343.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ SAMSHA News Release (16 February 2005). "North Dakota Tops Binge Drinking Stats". Health: Alcoholism. About.com.

- ^ "Overview of Key Findings 2007" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ^ The impact of alcohol in society

- ^ a b Anestasia M. Shkilnyk (March 11, 1985). A Poison Stronger than Love: The Destruction of an Ojibwa Community (trade paperback). Yale University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0300033257.

- ^ a b "Alcohol Consumption'' in Australia: A Snapshot, 2004–05". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 25 August 2006. 4832.0.55.001.

- ^ "Rudd sets aside $53-million to tackle binge drinking". PM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 March 2008.

- ^ "Binge drinking on people's minds: AMA". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 June 2008.

- ^ Lee J (24 April 2008). "Back to the bottle shop as drinkers stay at home". The Age.

- ^ "Minimum Drinking and Purchasing Age Laws" (PDF). International Center for Alcohol Policies. February 2007.

- ^ Palmer A (18 August 2009). "Binge drinking: Does Britain need to look to Italy to solve booze problem??". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- ^ Gee, Tony (26 March 2008). "Mayor seeks drinking age lift". NZ Herald. Retrieved 2012-12-23.

- ^ "Eye on Crime: Nights of extreme in Christchurch". The Press. 27 June 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hazardous drinking among New Zealand university students has its roots in high school". Eurekalert.org. 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2010-03-15.