Federalist No. 45

This article needs more links to other articles to help integrate it into the encyclopedia. (December 2016) |

Federalist No. 45

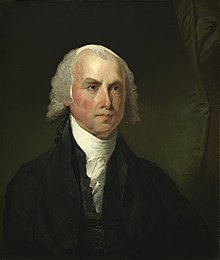

Federalist Paper No. 45: “The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered”, is the 45th out of 85 essays of the Federalist Papers series. No. 45 was written by James Madison, but was published under the pseudonym Publius, on January 26, 1788. The main focus of the essay is how the state and federal governments will function within the Union, while keeping the people’s happiness in mind.

Arguments Made

In Federalist 45, Madison argues that the Union as outlined in the Constitution is necessary to the people’s happiness and that the balance of power between the states and the national government will support the greatest happiness for the people. He argues that the primary purpose of government, and hence of the Constitution, is the people’s happiness, and therefore only a government that promotes the people’s happiness is legitimate, writing, “Were the plan of the Convention adverse to the public happiness, my voice would be , reject the plan. Were the Union itself inconsistent with the public happiness, it would be, abolish the Union”.[1]

Federal vs. State Governments

Madison notes the dangers and instabilities feared in a federal system, especially the concern that the national government could take too much power from the states or that the states might overthrow the national government, but argues that the federal system prevents this by being naturally harmonious and symbiotic; that the national government cannot operate without the state governments, while the state governments gain major benefits from the national government.

The state governments, Madison argues, are closer to the people and can focus on the welfare of the people, regulating ordinary affairs such as the lives, liberties, and properties of the people, as well as the internal order of each state, and should have numerous undefined powers to do so, while the national government, being bigger and possessing national resources, can bring victory in war, protect the people’s liberty, and maintain peace between the states, and should have clear, few, defined powers to do so, mostly focusing on external objects such as war, peace, negotiation, and foreign commerce and national taxation. He suggests that in times of peace, the state governments will tend to be larger and more powerful, while in times of crisis and war, the national government will expand as needed. Such a federal system will bring the government as a whole closer to the people than a purely national form of government would.

Historical Implications

Though Madison’s arguments and suggestions were considered, “any dispute about which is more powerful -- the federal government or the states -- was settled in 1789 when the Constitution granted the federal government the right to collect taxes, regulate interstate commerce, raise an army and adjudicate legal disputes between states”[2] States have consistently tried to nullify the federal government’s power, however, the federal government has always been victorious in avoiding it and still remain the more powerful of the two. The 10th Amendment, “the powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people”, has preserved the powers of the federal and state governments until present day since 1791.[3] This clarifies that the federal government powers are “few and defined” and the state government powers are “numerous and indefinite” even today, though, this is not always enforced by the federal government.

References

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2016) |

Notes

- ^ "Fallacies of negative constitutionalism". Fordham L. Rev. 75.

- ^ Judis, John (July 16, 2013). "Federal Government Is More Powerful Than State Government". New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Yoo, John. "Sounds of sovereignty: Defining federalism in the 1990s". Ind. L. Rev. 32.