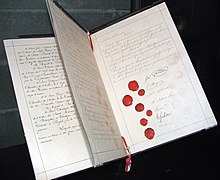

First Geneva Convention

The First Geneva Convention, for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field, is one of four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. It defines "the basis on which rest the rules of international law for the protection of the victims of armed conflicts."[1] It was first adopted in 1864, but was significantly updated in 1906, 1929, and 1949. It is inextricably linked to the International Committee of the Red Cross, which is both the instigator for the inception and enforcer of the articles in these conventions.

History

The First Geneva Convention was instituted at a critical period in European political and military history. Between the fall of the first Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 and the rise of his nephew in the Italian campaign of 1859, the powers had maintained peace in western Europe.[2] Yet, with the conflict in the Crimea, war had returned to Europe, and while those troubles were "in a distant and inaccessible region" northern Italy was "so accessible from all parts of western Europe that it instantly filled with curious observers;" while the bloodshed was not excessive the sight of it was unfamiliar and shocking.[2] Despite its intent of ameliorating the ravages of war the inception of the First Geneva Convention inaugurated "a renewal of military activity on a large scale, to which the people of western Europe… had not been accustomed since the first Napoleon had been eliminated."[2]

The movement for an international set of laws governing the treatment and care for the wounded and prisoners of war began when relief activist Henri Dunant witnessed the Battle of Solferino in 1859, fought between French-Piedmontese and Austrian armies in Northern Italy.[3] The subsequent suffering of 40,000 wounded soldiers left on the field due to lack of facilities, personnel, and truces to give them medical aid moved Dunant to action. Upon return to Geneva, Dunant published his account Un Souvenir de Solferino and through his membership in the Geneva Society for Public Welfare he urged the calling together of an international conference and soon helped found the International Committee of the Red Cross in 1863.[4]

The International Committee of the Red Cross, while recognizing that it is "primarily the duty and responsibility of a nation to safeguard the health and physical well-being of its own people," knew there would always, especially in times of war, be a "need for voluntary agencies to supplement… the official agencies charged with these responsibilities in every country."[5] To ensure that its mission was widely accepted it required a body of rules to govern its own activities and those of the involved belligerent parties.

On August 22, 1864 several European states congregated in Geneva, Switzerland and signed the First Geneva Convention:

- Baden (now Germany)

- Belgium

- Denmark

- France

- Hesse (now Germany)

- Italy

- Netherlands

- Portugal

- Prussia (now Germany)

- Spain

- Switzerland

- Württemberg (now Germany)

Norway and Sweden signed in December.

Not only was it the first, it was also the most basic and "derived its obligatory force from the implied consent of the states which accepted and applied them in the conduct of their military operations."[2] This first effort provided only for:

- the immunity from capture and destruction of all establishments for the treatment of wounded and sick soldiers,

- the impartial reception and treatment of all combatants,

- the protection of civilians providing aid to the wounded, and

- the recognition of the Red Cross symbol as a means of identifying persons and equipment covered by the agreement.[6]

Despite its basic mandates it was successful in effecting significant and rapid reforms.

Due to significant ambiguities in the articles with certain terms and concepts and even more so to the rapidly developing nature of war and military technology the original articles had to be revised and expanded, largely at the Second Geneva Convention in 1906 and Hague Convention of 1899 which extended the articles to maritime warfare.[7] It was updated again in 1929 when minor modifications were made to it. However, as Jean S. Pictet, Director of the International Committee of the Red Cross, noted in 1951, "the law, however, always lags behind charity; it is tardy in conforming with life’s realities and the needs of humankind," as such it is the duty of the Red Cross "to assist in the widening the scope of law, on the assumption that… law will retain its value," principally through the revision and expansion of these basic principles of the original Geneva Convention.[1]

Summary of provisions

The original ten articles of the 1864 treaty[8] have been expanded to the current 64 articles. This lengthy treaty protects soldiers that are hors de combat (out of the battle due to sickness or injury), as well as medical and religious personnel, and civilians in the zone of battle. Among its principal provisions:

- Article 12 mandates that wounded and sick soldiers who are out of the battle should be humanely treated, and in particular should not be killed, injured, tortured, or subjected to biological experimentation. This article is the keystone of the treaty, and defines the principles from which most of the rest the treaty is derived,[9] including the obligation to respect medical units and establishments (Chapter III), the personnel entrusted with the care of the wounded (Chapter IV), buildings and material (Chapter V), medical transports (Chapter VI), and the protective sign (Chapter VII).

- Article 15 mandates that wounded and sick soldiers should be collected, cared for, and protected, though they may also become prisoners of war.

- Article 16 mandates that parties to the conflict should record the identity of the dead and wounded, and transmit this information to the opposing party.

- Article 9 allows the International Red Cross "or any other impartial humanitarian organization" to provide protection and relief of wounded and sick soldiers, as well as medical and religious personnel.

For a detailed discussion of each article of the treaty, see the original text[10] and the commentary.[9] There are currently 194 countries party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, including this first treaty but also including the other three.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b Pictet, Jean S. (1951), "The New Geneva Conventions for the Protection of War Victims", The American Journal of International Law, 45 (3): 462–475

- ^ a b c d Davis, George B. (1907), "The Geneva Convention of 1906", The American Journal of International Law, 1 (2): 400+

- ^ Baxter, Richard (1977), "Human Rights in War", Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 31 (2): 5

- ^ Sperry, C.S. (1906), "The Revision of the Geneva Convention, 1906", Proceedings of the American Political Science Association, 3: 33

- ^ Anderson, Chandler P. (1920), "The International Red Cross Organization", The American Journal of International Law, 14 (1): 210

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. "Geneva Conventions", http://search.eb.com/ (accessed March 10, 2009).

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, "Geneva Conventions".

- ^ "Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. Geneva, 22 August 1864". The American National Red Cross. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ a b Pictet, Jean (1958). Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949: Commentary. International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ "Convention (I) for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. Geneva, 12 August 1949". The American National Red Cross. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ "States party to the main treaties". The American National Red Cross. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

Further reading

- Chandler P. Anderson, "International Red Cross Organization," The American Journal of International Law, 1920

- Richard Baxter, "Human Rights in War," Bulleting of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1977

- George B. Davis, "The Geneva Convention," The American Journal of International Law, 1907

- Jean S. Pictet, "The New Geneva Conventions for the Protection of War Victims," The American Journal of International Law, 1951

- Geneva Conventions

- Treaties concluded in 1949

- Treaties entered into force in 1950

- 1864 treaties

- Treaties of Afghanistan

- Treaties of the Socialist People's Republic of Albania

- Treaties of Algeria

- Treaties of Andorra

- Treaties of Angola

- Treaties of Antigua and Barbuda

- Treaties of Argentina

- Treaties of Armenia

- Treaties of Australia

- Treaties of the Second Austrian Republic

- Treaties of Azerbaijan

- Treaties of the Bahamas

- Treaties of Bahrain

- Treaties of Bangladesh

- Treaties of Barbados

- Treaties of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Treaties of Belgium

- Treaties of Belize

- Treaties of Benin

- Treaties of Bhutan

- Treaties of Bolivia

- Treaties of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Treaties of Botswana

- Treaties of Brazil

- Treaties of Brunei

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Bulgaria

- Treaties of Burkina Faso

- Treaties of Burma

- Treaties of Burundi

- Treaties of Cambodia

- Treaties of Cameroon

- Treaties of Canada

- Treaties of Cape Verde

- Treaties of the Central African Republic

- Treaties of Chad

- Treaties of Chile

- Treaties of the People's Republic of China

- Treaties of Colombia

- Treaties of Comoros

- Treaties of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of the Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of the Cook Islands

- Treaties of Costa Rica

- Treaties of Côte d'Ivoire

- Treaties of the Republic of Croatia

- Treaties of Cuba

- Treaties of Cyprus

- Treaties of the Czech Republic

- Treaties of Czechoslovakia

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of Djibouti

- Treaties of Dominica

- Treaties of the Dominican Republic

- Treaties of East Timor

- Treaties of Ecuador

- Treaties of Egypt

- Treaties of El Salvador

- Treaties of Equatorial Guinea

- Treaties of Eritrea

- Treaties of Estonia

- Treaties of Ethiopia

- Treaties of Fiji

- Treaties of Finland

- Treaties of the French Fourth Republic

- Treaties of Gabon

- Treaties of the Gambia

- Treaties of Georgia (country)

- Treaties of West Germany

- Treaties of East Germany

- Treaties of Ghana

- Treaties of the Kingdom of Greece

- Treaties of Grenada

- Treaties of Guatemala

- Treaties of Guinea

- Treaties of Guinea-Bissau

- Treaties of Guyana

- Treaties of Haiti

- Treaties of the Holy See

- Treaties of Honduras

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Hungary

- Treaties of Iceland

- Treaties of the Union of India

- Treaties of Indonesia

- Treaties of the Pahlavi dynasty

- Treaties of Iraq

- Treaties of Ireland

- Treaties of Israel

- Treaties of the Italian Republic

- Treaties of Jamaica

- Treaties of Japan

- Treaties of Jordan

- Treaties of Kazakhstan

- Treaties of Kenya

- Treaties of Kiribati

- Treaties of North Korea

- Treaties of South Korea

- Treaties of Kuwait

- Treaties of Kyrgyzstan

- Treaties of Laos

- Treaties of Latvia

- Treaties of Lebanon

- Treaties of Lesotho

- Treaties of Liberia

- Treaties of Libya

- Treaties of Liechtenstein

- Treaties of Lithuania

- Treaties of Luxembourg

- Treaties of the Republic of Macedonia

- Treaties of Madagascar

- Treaties of Malawi

- Treaties of Malaysia

- Treaties of the Maldives

- Treaties of Mali

- Treaties of Malta

- Treaties of the Marshall Islands

- Treaties of Mauritania

- Treaties of Mauritius

- Treaties of Mexico

- Treaties of the Federated States of Micronesia

- Treaties of Moldova

- Treaties of Monaco

- Treaties of Mongolia

- Treaties of Montenegro

- Treaties of Morocco

- Treaties of Mozambique

- Treaties of Namibia

- Treaties of Nauru

- Treaties of Nepal

- Treaties of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

- Treaties of New Zealand

- Treaties of Nicaragua

- Treaties of Niger

- Treaties of Nigeria

- Treaties of Norway

- Treaties of Oman

- Treaties of Pakistan

- Treaties of Palau

- Treaties of Panama

- Treaties of Papua New Guinea

- Treaties of Paraguay

- Treaties of Peru

- Treaties of the Philippines

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Poland

- Treaties of the Estado Novo (Portugal)

- Treaties of Qatar

- Treaties of the Socialist Republic of Romania

- Treaties of Rwanda

- Treaties of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Treaties of Saint Lucia

- Treaties of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Treaties of Samoa

- Treaties of San Marino

- Treaties of São Tomé and Príncipe

- Treaties of Saudi Arabia

- Treaties of Senegal

- Treaties of Serbia and Montenegro

- Treaties of Seychelles

- Treaties of Sierra Leone

- Treaties of Singapore

- Treaties of Slovakia

- Treaties of Slovenia

- Treaties of the Solomon Islands

- Treaties of Somalia

- Treaties of the Union of South Africa

- Treaties of the Soviet Union

- Treaties of Francoist Spain

- Treaties of Sri Lanka

- Treaties of Sudan

- Treaties of Suriname

- Treaties of Swaziland

- Treaties of Sweden

- Treaties of the Swiss Confederation

- Treaties of Syria

- Treaties of Tajikistan

- Treaties of Tanzania

- Treaties of Thailand

- Treaties of Togo

- Treaties of Tonga

- Treaties of Trinidad and Tobago

- Treaties of Tunisia

- Treaties of Turkey

- Treaties of Turkmenistan

- Treaties of Tuvalu

- Treaties of Uganda

- Treaties of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Treaties of the United Arab Emirates

- Treaties of the United Kingdom

- Treaties of the United States

- Treaties of Uruguay

- Treaties of Uzbekistan

- Treaties of Vanuatu

- Treaties of Venezuela

- Treaties of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam

- Treaties of Yemen

- Treaties of North Yemen

- Treaties of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

- Treaties of Zambia

- Treaties of Zimbabwe