Frequency modulation synthesis

|

|

|

In audio and music, frequency modulation synthesis (or FM synthesis) is a form of audio synthesis where the timbre of a simple waveform (such as a square, triangle, or sawtooth) is changed by modulating its frequency with a modulator frequency that is also in the audio range, resulting in a more complex waveform and a different-sounding tone that can also be described as "gritty" if it is a thick and dark timbre. The frequency of an oscillator is altered or distorted, "in accordance with the amplitude of a modulating signal." (Dodge & Jerse 1997, p. 115)

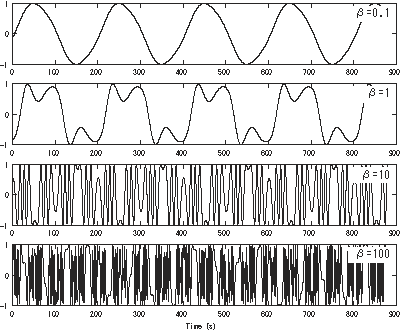

FM synthesis can create both harmonic and inharmonic sounds. For synthesizing harmonic sounds, the modulating signal must have a harmonic relationship to the original carrier signal. As the amount of frequency modulation increases, the sound grows progressively more complex. Through the use of modulators with frequencies that are non-integer multiples of the carrier signal (i.e. non-harmonic), atonal and tonal bell-like and percussive sounds can easily be created.

FM synthesis using analog oscillators may result in pitch instability. However, FM synthesis can also be implemented digitally, the latter proving to be more 'reliable' and is currently seen as standard practice. Digital FM synthesis (using the more frequency-stable phase modulation variant) was the basis of several musical instruments beginning as early as 1974. Yamaha built the first prototype digital synthesizer in 1974, based on FM synthesis,[1] before commercially releasing the Yamaha GS-1 in 1980.[2] The Synclavier I, manufactured by New England Digital Corporation beginning in 1978, included a digital FM synthesizer, using an FM synthesis algorithm licensed from Yamaha.[3] Yamaha's groundbreaking DX7, released in 1983, brought FM to the forefront of synthesis in the mid-1980s.

History

The technique of the digital implementation of frequency modulation, which was developed by John Chowning (Chowning 1973, cited in Dodge & Jerse 1997, p. 115) at Stanford University in 1967–68, was patented in 1975. Prior to that, the FM synthesis algorithm was licensed to Japanese company Yamaha in 1973.[1] It was initially designed for radios to transmit voice by modulating one waveform's frequency with another's. This is why FM radio is called FM (frequency modulation).

The implementation commercialized by Yamaha (US Patent 4018121 Apr 1977[4] or U.S. Patent 4,018,121[5]) is actually based on phase modulation, but the results end up being equivalent mathematically as both are essentially a special case of QAM, with phase modulation simply making the implementation resilient against undesirable drift in frequency of carrier waves due to self-modulation or due to DC bias in the modulating wave.[6]

Yamaha's engineers began adapting Chowning's algorithm for use in a commercial digital synthesizer, adding improvements such as the "key scaling" method to avoid the introduction of distortion that normally occurred in analog systems during frequency modulation, though it would take several years before Yamaha were to release their FM digital synthesizers.[7] In the 1970s, Yamaha were granted a number of patents, under the company's former name "Nippon Gakki Seizo Kabushiki Kaisha", evolving Chowning's early work on FM synthesis technology.[5] Yamaha built the first prototype FM digital synthesizer in 1974.[1] Yamaha eventually commercialized FM synthesis technology with the Yamaha GS-1, the first FM digital synthesizer, released in 1980.[2]

As noted earlier, FM synthesis was the basis of some of the early generations of digital synthesizers, most notably those from Yamaha, as well as New England Digital Corporation under license from Yamaha.[3] Yamaha's popular DX7 synthesizer, released in 1983, was ubiquitous throughout the 1980s. Several other models by Yamaha provided variations and evolutions of FM synthesis during that decade.

Yamaha had patented its hardware implementation of FM in the 1970s,[5] allowing it to nearly monopolize the market for FM technology until the mid-1990s. Casio developed a related form of synthesis called phase distortion synthesis, used in its CZ range of synthesizers. It had a similar (but slightly differently derived) sound quality to the DX series. Don Buchla implemented FM on his instruments in the mid-1960s, prior to Yamaha's patent. His 158, 258 and 259 dual oscillator modules had a specific FM control voltage input,[8] and the model 208 (Music Easel) had a modulation oscillator hard-wired to allow FM as well as AM of the primary oscillator.[9] These early applications used analog oscillators, and this capability was also followed by other modular synthesizers and portable synthesizers including Minimoog and ARP Odyssey.

With the expiration of the Stanford University FM patent in 1995, digital FM synthesis can now be implemented freely by other manufacturers. The FM synthesis patent brought Stanford $20 million before it expired, making it (in 1994) "the second most lucrative licensing agreement in Stanford's history".[10] FM today is mostly found in software-based synths such as FM8 by Native Instruments or Sytrus by Image-Line, but it has also been incorporated into the synthesis repertoire of some modern digital synthesizers, usually coexisting as an option alongside other methods of synthesis such as subtractive, sample-based synthesis, additive synthesis, and other techniques. The degree of complexity of the FM in such hardware synths may vary from simple 2-operator FM, to the highly flexible 6-operator engines of the Korg Kronos and Alesis Fusion, to creation of FM in extensively modular engines such as those in the latest synthesisers by Kurzweil Music Systems.

New hardware synths specifically marketed for their FM capabilities disappeared from the market after the release of the Yamaha SY99 and FS1R, and even those marketed their highly powerful FM abilities as counterparts to sample-based synthesis and formant synthesis respectively. However, well-developed FM synthesis options are a feature of Nord Lead synths manufactured by Clavia, the Alesis Fusion range, the Korg Oasys and Kronos and the Modor NF-1. Various other synthesizers offer limited FM abilities to supplement their main engines.

Most recently, in 2016, Korg released the Korg Volca FM, an FM iteration of the Korg Volca series of compact, affordable desktop modules, and Yamaha released the Montage, which combines a 128-voice sample-based engine with a 128-voice FM engine. This iteration of FM is called FM-X, and features 8 operators; each operator has a choice of several basic wave forms, but each wave form has several parameters to adjust its spectrum.

FMX synthesis was introduced with the Yamaha Montage synthesizers in 2016. FMX uses 8 operators. Each FMX operator has a set of multi-spectral wave forms to choose from, which means each FMX operator can be equivalent to a stack of 3 or 4 DX7 FM operators. The list of selectable wave forms includes sine waves, the All1 and All2 wave forms, the Odd1 and Odd2 wave forms, and the Res1 and Res2 wave forms. The sine wave selection works the same as the DX7 wave forms. The All1 and All2 wave forms are a saw-tooth wave form. The Odd1 and Odd2 wave forms are pulse or square waves. These two types of wave forms can be used to model the basic harmonic peaks in the bottom of the harmonic spectrum of most instruments. The Res1 and Res2 wave forms move the spectral peak to a specific harmonic and can be used to model either triangular or rounded groups of harmonics further up in the spectrum of an instrument. Combining an All1 or Odd1 wave form with multiple Res1 (or Res2) wave forms (and adjusting their amplitudes) can model the harmonic spectrum of an instrument or sound. [citation needed]

Combining sets of 8 FM operators with multi-spectral wave forms began in 1999 by Yamaha in the FS1R. The FS1R had 16 operators, 8 standard FM operators and 8 additional operators that used a noise source rather than an oscillator as its sound source. By adding in tuneable noise sources the FS1R could model the sounds produced in the human voice and in a wind instrument, along with making percussion instrument sounds. The FS1R also contained an additional wave form called the Formant wave form. Formants can be used to model resonating body instrument sounds like the cello, violin, acoustic guitar, bassoon, English horn, or human voice. Formants can even be found in the harmonic spectrum of several brass instruments. [citation needed]

Spectral analysis

The spectrum generated by FM synthesis with one modulator is expressed as follows:[11][12]

For modulation signal , the carrier signal is

If we were to ignore the constant phase terms on the carrier and the modulator , finally we would get the following expression, as seen on Chowning 1973 and Roads 1996, p. 232:

where are angular frequencies () of carrier and modulator, is frequency modulation index, and amplitudes is -th Bessel function of first kind, respectively.[note 1]

Footnote

- ^

above expression is transformed using trigonometric addition formulas

- (Source: Kreh, Martin (2012), "Bessel Function" (PDF), Gottingen Summer School on Number Theory, Gottingen, Germany, July 29, 2012 – August 18, 2012, pp. 5–6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link))

See also

- Additive synthesis

- Chiptune

- Digital synthesizer

- Electronic music

- Sound card

- Sound chip

- Video game music

Citations

- ^ a b c "[Chapter 2] FM Tone Generators and the Dawn of Home Music Production". Yamaha Synth 40th Anniversary - History. Yamaha Corporation. 2014.

- ^ a b Curtis Roads (1996). The computer music tutorial. MIT Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-262-68082-3. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ a b "1978 New England Digital Synclavier". Mix. Penton Media. September 1, 2006.

- ^ "U.S. Patent 4018121 Apr 1977". patft.uspto.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ^ a b c "Patent US4018121 - Method of synthesizing a musical sound - Google Patents". google.com. Retrieved 2017-04-30.

- ^ Rob Hordijk. "FM synthesis on Modular". Nord Modular & Micro Modular V3.03 tips & tricks. Clavia DMI AB.

- ^ Holmes, Thom (2008). "Early Computer Music". Electronic and experimental music: technology, music, and culture (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. pp. 257–8. ISBN 0-415-95781-8. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ^

Dr. Hubert Howe (1960s). Buchla Electronic Music System: Users Manual written for CBS Musical Instruments (Buchla 100 Owner's Manual). Educational Research Department, CBS Musical Instruments, Columbia Broadcasting System. p. 7.

At this point we may consider various additional signal modifications that we may wish to make to the series of tones produced by the above example. For instance, if we would like to add frequency modulation to the tones, it is necessary to patch another audio signal into the jack connected by a line to the middle dial on the Model 158 Dual Sine-Sawtooth Oscillator. ...

- ^ Atten Strange (1974). Programming and Metaprogramming in the Electro-Organism - An Operating Directive for the Music Easel. Buchla and Associates.

- ^ Stanford University News Service (06/07/94), Music synthesis approaches sound quality of real instruments

- ^ Chowning 1973, pp. 1–2

- ^ Doering, Ed. "Frequency Modulation Mathematics". Retrieved 2013-04-11.

References

- Chowning, J. (1973). "The Synthesis of Complex Audio Spectra by Means of Frequency Modulation" (PDF). Journal of the Audio Engineering Society. 21 (7).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) (also available in PDF as digital version 2/13/2007) - Chowning, John; Bristow, David (1986). FM Theory & Applications - By Musicians For Musicians. Tokyo: Yamaha. ISBN 4-636-17482-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roads, Curtis (1996). The Computer Music Tutorial. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-68082-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dodge, Charles; Jerse, Thomas A. (1997). Computer Music: Synthesis, Composition and Performance. New York: Schirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-864682-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- An Introduction To FM, by Bill Schottstaedt

- FM tutorial

- Synth Secrets, Part 12: An Introduction To Frequency Modulation, by Gordon Reid

- Synth Secrets, Part 13: More On Frequency Modulation, by Gordon Reid

- Paul Wiffens Synth School: Part 3

- F.M. Synthesis including complex operator analysis

- Part 1 of a 2-part YouTube tutorial on FM synthesis with numerous audio examples

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}FM(t)&\ \approx \ A\,\sin \left(\omega _{c}\,t+\beta \,\sin(\omega _{m}\,t)\right)\\&\ =\ A\left(J_{0}(\beta )\sin(\omega _{c}\,t)+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }J_{n}(\beta )\left[\,\sin((\omega _{c}+n\,\omega _{m})\,t)\ +\ (-1)^{n}\sin((\omega _{c}-n\,\omega _{m})\,t)\,\right]\right)\\&\ =\ A\sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }J_{n}(\beta )\,\sin((\omega _{c}+n\,\omega _{m})\,t)\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2245df5dbe5a6c9f04835df2d4e89f07728a81e1)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&\sin \left(\theta _{c}+\beta \,\sin(\theta _{m})\right)\\&\ =\ \sin(\theta _{c})\cos(\beta \sin(\theta _{m}))+\cos(\theta _{c})\sin(\beta \sin(\theta _{m}))\\&\ =\ \sin(\theta _{c})\left[J_{0}(\beta )+2\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }J_{2n}(\beta )\cos(2n\theta _{m})\right]+\cos(\theta _{c})\left[2\sum _{n=0}^{\infty }J_{2n+1}(\beta )\sin((2n+1)\theta _{m})\right]\\&\ =\ J_{0}(\beta )\sin(\theta _{c})+J_{1}(\beta )2\cos(\theta _{c})\sin(\theta _{m})+J_{2}(\beta )2\sin(\theta _{c})\cos(2\theta _{m})+J_{3}(\beta )2\cos(\theta _{c})\sin(3\theta _{m})+...\\&\ =\ J_{0}(\beta )\sin(\theta _{c})+\sum _{n=1}^{\infty }J_{n}(\beta )\left[\,\sin(\theta _{c}+n\theta _{m})\ +\ (-1)^{n}\sin(\theta _{c}-n\theta _{m})\,\right]\\&\ =\ \sum _{n=-\infty }^{\infty }J_{n}(\beta )\,\sin(\theta _{c}+n\theta _{m})\qquad (\because \ J_{-n}(x)=(-1)^{n}J_{n}(x))\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/75361ca6bdbbe660138b6b060475a5284a9d7b9b)