Gallbladder: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

m →Human anatomy: Grammar/style |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{lead too short|date=April 2010}} |

{{lead too short|date=April 2010}} |

||

{{Infobox Anatomy |

{{Infobox Anatomy |

||

| Name = |

| Name = Tw is a lad :) |

||

| Latin = vesica fellea; vesica biliaris |

| Latin = vesica fellea; vesica biliaris |

||

| GraySubject = 250 |

| GraySubject = 250 |

||

Revision as of 19:34, 15 November 2011

| Tw is a lad :) | |

|---|---|

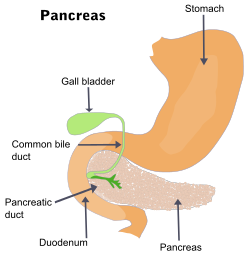

Diagram of Stomach | |

Surface projections of the organs of the trunk, with gallbladder labeled at the transpyloric plane. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Foregut |

| System | Digestive system (GI Tract) |

| Artery | Cystic artery |

| Vein | Cystic vein |

| Nerve | Celiac ganglia, vagus[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vesica fellea; vesica biliaris |

| MeSH | D005704 |

| TA98 | A05.8.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3081 |

| FMA | 7202 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

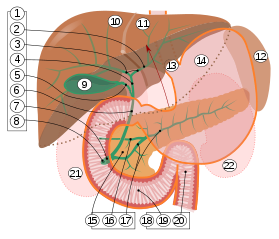

2. Intrahepatic bile ducts

3. Left and right hepatic ducts

4. Common hepatic duct

5. Cystic duct

6. Common bile duct

7. Ampulla of Vater

8. Major duodenal papilla

9. Gallbladder

10–11. Right and left lobes of liver

12. Spleen

13. Esophagus

14. Stomach

15. Pancreas:

16. Accessory pancreatic duct

17. Pancreatic duct

18. Small intestine:

19. Duodenum

20. Jejunum

21–22. Right and left kidneys

The front border of the liver has been lifted up (brown arrow).[2]

In vertebrates the gallbladder (cholecyst, gall bladder, Biliary Vesicle) is a small organ that aids mainly in fat digestion and concentrates bile produced by the liver. In humans the loss of the gallbladder is usually easily tolerated.

Human anatomy

The gallbladder is a hollow system that sits just beneath the liver.[3] In adults, the gallbladder measures approximately 8 centimetres (3.1 in) in length and 4 centimetres (1.6 in) in diameter when fully distended.[4] It is divided into three sections: fundus, body and neck. The neck tapers and connects to the biliary tree via the cystic duct, which then joins the common hepatic duct to become the common bile duct. At the neck of the gall bladder is a mucosal fold called Hartmann's pouch, where gallstones commonly get stuck. The angle of the gallbladder is located between the costal margin and the lateral margin of the rectus abdominis muscle.

Microscopic anatomy

The different layers of the gallbladder are as follows:[5]

- The epithelium, a thin sheet of cells closest to the inside of the gallbladder

- The lamina propria, a thin layer of loose connective tissue (the epithelium plus the lamina propria form the mucosa)

- The muscularis, a layer of smooth muscular tissue that helps the gallbladder contract, squirting its bile into the bile duct

- The perimuscular ("around the muscle") fibrous tissue, another layer of connective tissue

- The serosa, the outer covering of the gallbladder that comes from the peritoneum, which is the lining of the abdominal cavity

Unlike elsewhere in the intestinal tract, the gallbladder does not have a muscularis mucosae.

Function

When food containing fat enters the digestive tract, it stimulates the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK). In response to CCK, the adult human gallbladder, which stores about 50 milliliters (1.7 U.S. fl oz; 1.8 imp fl oz) of bile, releases its contents into the duodenum. The bile, originally produced in the liver, emulsifies fats in partly digested food.

During storage in the gallbladder, bile becomes more concentrated which increases its potency and intensifies its effect on fats.

In 2009, it was demonstrated that the gallbladder removed from a patient expressed several pancreatic hormones including insulin.[6] This was surprising because until then, it was thought that insulin was only produced in pancreatic β-cells. This study provides evidence that β-like cells do occur outside the human pancreas. The authors suggest that since the gallbladder and pancreas are adjacent to each other during embryonic development, there exists tremendous potential in derivation of endocrine pancreatic progenitor cells from human gallbladders that are available after cholecystectomy.

In animals

Most vertebrates have gallbladders, whereas invertebrates do not. However, its precise form and the arrangement of the bile ducts may vary considerably. In many species, for example, there are several separate ducts running to the intestine, rather than a single common bile duct, as in humans. Several species of mammals (including horses, deer, rats, and various lamoids[7]) and several species of birds lack a gallbladder altogether, as do lampreys.[8]

See also

References

- ^ Ginsburg, Ph.D., J.N. (2005-08-22). "Control of Gastrointestinal Function". In Thomas M. Nosek, Ph.D. (ed.). Gastrointestinal Physiology. Essentials of Human Physiology. Augusta, Georgia, United State: Medical College of Georgia. pp. p. 30. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Standring S, Borley NR, eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice. Brown JL, Moore LA (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 1163, 1177, 1185–6. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

- ^ http://www.buzzle.com/articles/where-is-the-gallbladder-located-in-the-body.html

- ^ Jon W. Meilstrup (1994). Imaging Atlas of the Normal Gallbladder and Its Variants. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-8493-4788-2.

- ^ "Staging of Gallbladder Cancer".

- ^ Sahu S, Joglekar MV, Dumbre R, Phadnis SM, Tosh D, Hardikar AA. (2009) Islet-like cell clusters occur naturally in human gall bladder and are retained in diabetic conditions. J Cell Mol Med. 2009 May;13(5):999-1000

- ^ C. Michael Hogan. 2008. Guanaco: Lama guanicoe, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Strömberg

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 355. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

- Diagram of Human Stomach and Gallbladder – Human Anatomy Online, MyHealthScore.com.

- www.newchronicles.webs.com/f/gastrointestinalphysiology – Gastrointestinal Physiology Review.