Garamond

| |

| Category | Serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Old-style |

| Designer(s) | Claude Garamond Jean Jannon |

| Shown here | Adobe Garamond Pro (based on the original Garamond) |

Garamond is the name given to many old-style serif typefaces, after the latinized name of the 16th-century punch-cutter Claude Garamont.

Some unique characteristics in his letters are the small bowl of the a and eye of the e. Long extenders and top serifs have a downward slope. Like all old-style designs, variation in stroke width is restrained in a way that resembles handwriting, creating a design that seems organic and unadorned. Although there is no conclusive evidence from legibility studies,[1] Garamond is considered to be among the most legible and naturally readable serif typefaces when printed on paper.[2][3]

Many Garamond revivals are more closely related to the work of a later punch-cutter, Jean Jannon, or incorporate italic designs created by Robert Granjon. Among contemporary typefaces, the Roman versions of Adobe Garamond, Granjon, Sabon, and Stempel Garamond are directly based on Garamond’s work. Modern Garamond revivals also often create matching bold designs, which did not exist in Garamond's time.[4] The most common digital release of Garamond is Monotype Garamond, bundled with many Microsoft products.[5]

History

Original type

The first Roman type designed by Claude Garamond was used in an edition of the Erasmus book Paraphrasis in Elegantiarum Libros Laurentii Vallae published in 1530. The Roman design was based on an Aldus Manutius type, De Aetna, cut in 1495-1496 by Francesco Griffo. After Claude Garamond died in 1561, most of his punches and matrices were acquired by Christophe Plantin from Antwerp, the Le Bé type foundry and the Frankfurt foundry Egenolff-Berner.[6]

The only complete set of the original Garamond dies and matrices is at the Plantin-Moretus Museum, in Antwerp, Belgium.

The term Garamond is today mostly applied to Garamond's designs for the Latin alphabet. Garamond designed type for the Greek alphabet, but these, the glamorous and fluid Grecs du roi, are very different to his Latin designs: they mimic the elegant handwriting of scribes and contain a vast variety of ligatures and alternate glyphs to achieve this. As these are quite impractical for modern printing, several 'Garamond' releases such as Adobe's contain Greek designs that are either a compromise between Garamond's upright Latin designs and his slanted Greek ones or primarily inspired by his Latin designs.

Jean Jannon misattribution

In 1621, sixty years after Garamond’s death, the French printer Jean Jannon issued a specimen of typefaces that had some characteristics similar to the Garamond designs, though his letters were more asymmetrical and irregular in slope and axis. Jannon was a Protestant, making him a target of governmental suspicion. After the French government raided Jannon’s printing office, Cardinal Richelieu named Jannon’s type Caractère de l’Université (literally "Character of the University"),[7] and it became the house style of Royal Printing Office.

In 1825, the French National Printing Office adapted the type used by Royal Printing Office in the past, and claimed the type as the work of Claude Garamond.

Several revivals were produced in the early 20th century. However, in a 1926 paper published on the British typography journal The Fleuron, Beatrice Warde revealed that many of the revivals said to be based on Claude Garamond’s designs actually followed Jean Jannon's designs. Nevertheless the Garamond name had stuck.

Typefaces derived from Jannon's design include Monotype Garamond, Simoncini Garamond, LTC Garamont, and Linotype Garamond 3. This grouping also includes a version called ITC Garamond, designed by Tony Stan (1917–1988) of the International Typeface Corporation and released in 1977. It was initially intended to serve as a display version accompanying existing typefaces, and is considered by some to be only loosely based on Garamond and Jannon's designs.

Jannon-derived types are most immediately recognizable by the lowercase a, which has a long upper hook that extends slightly past the edge of the bowl; the bowl itself is smaller and more downward-pointing than those of Garamond. Other differences include the triangular serifs on the stems of such characters as m, n and r, which are more steeply inclined and concave in Jannon's design than in Garamond's.

Revivals based on Garamond's original face include Adobe Garamond and Garamond Premier (both designed by Robert Slimbach), Ludlow Garamond, Stempel Garamond, URW++ Garamond No 8, Granjon (designed by George William Jones) and Sabon (designed by Jan Tschichold).

Contemporary versions

Based on Garamond's design

Adobe Garamond

Released in 1989, Adobe Garamond is designed by Robert Slimbach for Adobe Systems, based on the Roman types of Garamond and the Italic types of Robert Granjon.[8] The font family contains regular, semibold, and bold weights and was developed through viewing fifteenth-century equipment at the Plantin-Moretus Museum. Its quite even, mature design attracted attention on release for its authenticity to Garamond's work, a contrast to the much more aggressive ITC Garamond popular at the time.[9] The OpenType version of the font family was released in 2000 as Adobe Garamond Pro, with enhanced support for its alternate glyphs such as swashes, and is sold through Adobe's Typekit system. It is one of the most popular versions of Garamond in books and fine printing.[10]

Garamond Premier

Slimbach started planning for a second interpretation of Garamond after visiting the Plantin-Moretus Museum in 1988, during the production of Adobe Garamond. It was released in 2005 as Garamond Premier Pro, in a range of optical sizes, each designed in four weights (regular, medium, semibold and bold, with an additional light weight for display sizes) using the OpenType font format. It features glyph coverage for Central European, Cyrillic and Greek characters.[11][12]

Stempel Garamond

A hot-metal period adaptation created by the Stempel Type Foundry in the interwar period, and released through Linotype in other countries. It has relatively short descenders, allowing it to be particularly tightly linespaced. An unusual feature is the digit 0, which has reversed contrast.

Sabon

Sabon is a Garamond revival designed by Jan Tschichold in 1964, jointly released by Linotype, Monotype and Stempel in 1967. It is named after Jacques Sabon, who introduced Garamond's types to German printing. A distinguishing feature of Sabon is that the italic is wider than most normal italics, at the same width as the roman style.

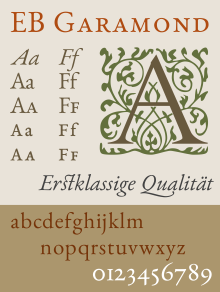

EB Garamond

Released in 2011 by Georg Duffner, EB Garamond is a free software version of Garamond released under the Open Font License and available through Google Fonts. Duffner based the design on a specimen printed by Egelnoff-Berner in 1592, with italic and Greek characters based on Robert Granjon's work, as well as the addition of Cyrillic characters and OpenType features such as swashes.[13] It is intended to include multiple optical sizes, as of 2014 including fonts based on the 8 and 12 point forms on the 1592 specimen. It has been described as 'one of the best open source fonts' by prominent typeface designer Erik Spiekermann.[14]

URW++ Garamond No. 8

Garamond No. 8 is a freeware version of Garamond contributed by URW++ to the Ghostscript project under the AFP license, based on Stempel Garamond. Featuring a bold weight, small capitals, optional text figures and automatic ligature insertion, it is particularly popular in the TeX community and is also included on some Linux distributions. Originally released as a PostScript Type 1, it has been converted into the TrueType format, usable by most current software.[15]

Based on Jannon's design

Garamond 3

This 1936 version was created by Morris Fuller Benton and American Type Founders and named to distinguish it from an earlier version created by Benton and T.M. Cleland; it was licensed to and marketed by Linotype.[16][17] It was the style of Garamond preferred by prominent designer Massimo Vignelli and Spy magazine.[18] A variant is used by Deutsche Bahn.[19]

Monotype Garamond

Monotype's 1922 design, based on Jannon's work, is bundled with many Microsoft products.[20] It features an extremely calligraphic italic, with a very variable angle of slant and swashes on many lower-case letters.[21] Its commercial release is much more extensive than that bundled with Microsoft products, featuring additional features such as swash caps and small capitals, although like many pre-digital fonts these are only included in the regular weight. Popular in the metal type era, its digitisation has been criticised for being too light, a feature of many Monotype digitisations of the period, making it less well suited to body text.[22][23][24]

ITC Garamond

ITC Garamond was created by Tony Stan in 1975, and follows ITC's house style of unusually high x-height, giving it a somewhat hectoring appearance. As a result, it has proven somewhat controversial among designers for its perceived clumsiness and inauthenticity; it is generally considered unsuitable for body text.[25] It was nevertheless adopted as a signature typeface for O'Reilly Media's books until switching to Adobe Minion in the mid-2000s. It is still used by French publisher Actes Sud. As seen below, it was also modified into Apple Garamond which served as Apple's corporate font from 1984 until replacement with Myriad in 2002. It remains the corporate font of the California State University system in printed text.[26]

Related fonts

As one of the most popular typefaces in history, a number of designs have been created that parody or distort Garamond, or convert its letterforms into a sans-serif design.

Cormorant

An extremely slender open-source adaptation of Garamond intended for display sizes, designed by astrophysicist Christian Thalmann.[27][28] It features unusual alternate designs such as an upright italic and unicase styles.[27] It was co-released with Google Fonts.

Classiq

Classiq is a sans-serif font designed by Yamaoka Yasuhiro, based on Garamond's structure and shape together with influences from Jannon and Granjon's designs. Its design includes six weights from light to heavy together with strongly cursive italic designs. Released in 2002 through the designer's type foundry YOFonts, it is a free but not open source font.[29][30]

Aragon Sans

Designed by Hans van Maanen and a released by Canada Type, Aragon Sans is a sans-serif derivative of his previous serif design Aragon, creating a font superfamily.[31]

Printer ink usage

It has been claimed that Garamond uses much less ink than Times New Roman at a similar point size, so changing to Garamond could be a cost-saver for large organizations that print large numbers of documents, especially if using inkjet printers.[32][33]

However, this claim has been criticised as a mis-interpretation of how typefaces are actually measured. Monotype Garamond, the version bundled with Microsoft Windows, has shorter characters (x-height) at the same point size compared to Times New Roman and quite spindly strokes, giving it a more elegant but less readable appearance. To make lower-case letters as high as in an equivalent setting of Times New Roman, the text size must be increased, counterbalancing the effect. Thomas Phinney, an expert on font design, noted that the effect of simply swapping Garamond in would be compromised legibility: "any of those changes, swapping to a font that sets smaller at the same nominal point size, or actually reducing the point size, or picking a thinner typeface, will reduce the legibility of the text. That seems like a bad idea, as the percentage of Americans with poor eyesight is skyrocketing."[34] Nonetheless, Garamond, along with Times New Roman and Century Gothic, has been identified by the GSA as a "toner-efficient" font.[35]

In popular culture

- In Umberto Eco's novel Il pendolo di Foucault, the protagonists work for a pair of related publishing companies, Garamond and Manuzio, both owned by a Mister Garamond.

- Garamond is the name of a character in the Wii game Super Paper Mario. He appears in the world of Flopside (the mirror-image of Flipside, where the game begins). He is a prolific and highly successful author, unlike his Flipside counterpart, Helvetica (a probable recognition of the relative suitability of the two fonts for use in book typesetting).

- The large picture books of Dr. Seuss are set in a version of Garamond.

- In 1988 British newspaper The Guardian redesigned its masthead to incorporate "The" in Garamond and "Guardian" in bold Helvetica. This led to a repopularising of Garamond in the UK.[citation needed]

- Nvidia uses it in their scientific PDF documents.[37]

- The Everyman's Library publication of 'The Divine Comedy is set in twelve-point Garamond.

- A variation on the Garamond typeface was adopted by Apple in 1984 upon the release of the Macintosh. For branding and marketing the new Macintosh family of products, Apple's designers used the ITC Garamond Light and Book weights and digitally condensed them twenty percent. The result was not as compressed as ITC Garamond Light Condensed or ITC Garamond Book Condensed. Not being a multiple master font, stroke contrast in some characters was too light, and some of the interior counters appeared awkward. To address these problems, Apple commissioned ITC and Bitstream to develop a variant for their proprietary use that was similar in width and feeling, but addressed the digitally condensed version’s shortcomings. Designers at Bitstream produced a unique digital variant, condensed approximately twenty percent, and worked with Apple to make the face more distinct. Following this, Chuck Rowe hinted the TrueTypes. The fonts delivered to Apple were known as Apple Garamond.[38]

- One of the initial goals of the literary journal Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern was to use only a single font: Garamond 3. The editor of the journal, Dave Eggers, has stated that it is his favorite font, "because it looked good in so many permutations—italics, small caps, all caps, tracked out, justified or not."[39]

- Many O’Reilly Media books are set in ITC Garamond Light.

- The logo of clothing company Abercrombie & Fitch uses a variation of the Garamond typeface.

- Garamond text is used on 1985 Nintendo video game consoles in italic form (after the text "Nintendo Entertainment System" or NES) to describe the various version of the consoles.[citation needed]

- In Robin Sloan's novel "Mr. Penumbra'a 24-Hour Bookstore: A Novel", Claude Garamont is fictionalized as Griffo Gerritszoon. The main character's name, Clay Jannon, as well as many other character names derive from historical figures associated with the Garamond typeface.[40]

An infant or schoolbook design of Garamond - A rare infant version—with single-story versions of the letters a and g—was sold in the UK from DTP Types. EB Garamond and Cormorant also provide these designs as a stylistic alternate.

Notes

- ^ http://alexpoole.info/blog/which-are-more-legible-serif-or-sans-serif-typefaces/

- ^ "Review of Classic Serif Typefaces".

- ^ Coale, Brian (8 October 2013). "#FontFriday: Garamond, the Eco-Friendly Font". Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Haley, Allan. "Bold type in text". Monotype. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Phinney, Thomas (28 March 2014). "Saving $400M printing cost from font change? Not Exactly…". Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Claude Garamond". linotype.com. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ "Garamond & the Boys".

- ^ "Adobe Garamond Pro specimen book" (PDF). Adobe Systems. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Riggs, Tamye. "Stone, Slimbach, and Twombly launch the first Originals". Typekit blog. Adobe. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. "Top Ten Typefaces Used by Book Design Winners". FontFeed. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Adobe - Fonts: Garamond Premier Pro". Adobe Systems. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ Phinney, Thomas. "Comments on Garamond Premier Pro". Typophile (discussion thread). Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Duffner, Georg. "EB Garamond specimen". Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ Spiekermann, Erik. "Twitter post". Twitter. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Hosny, Khaled. "URW Garamond ttf conversions". Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Shaw, Paul. "The Mystery of Garamond no. 3". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Shaw, Paul. "More on Garamond no. 3 (and some notes on Gutenberg)". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- ^ Bierut, Michael. "Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Typeface". Design Observer. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, Christian. "DB". Schwartzco. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "Garamond". Microsoft. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Monotype Garamond". Fonts.com. Monotype. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Matteson, Steve. "Type Q&A: Steve Matteson from Monotype". Monotype. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Kobayashi, Akira. "Akira Kobayashi on FF Clifford". FontFeed. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Hendel, Richard (1998). On book design. New Haven [u.a.]: Yale Univ. Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780300075700.

- ^ Bierut, Michael. "I Hate ITC Garamond". Design Observer. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ^ Grey, Marge. "Serif Type Family: ITC Garamond". California State University. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Cormorant". Behance. Catharsis Fonts. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Thalmann, Christian. "Christian Thalmann fonts page". Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Yasuhiro, Yamaoka. "Classiq". YOFonts.

- ^ "Classiq specimen booklet" (PDF). YOFonts.

- ^ "Aragon Sans". MyFonts. Canada Type/Monotype.

- ^ Stix, Madeleine (March 28, 2014). Teen to gov't: change your typeface, save millions. CNN via KOCO-TV. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ^ Agarwal, Amit (19 July 2012). "Which Fonts Should You Use for Saving Printer Ink". Digital Inspiration. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Phinney, Thomas. "Save $400M printing cost from font change? Not so fast…". Phinney on Fonts. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ "Toner-Efficient Fonts Can Save Millions". Department of the Navy. 8 March 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-12-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Valerie R. Hotchkiss, Charles C. Ryrie (1998). "Formatting the Word of God: An Exhibition at Bridwell Library".

- ^ "NVIDIA OpenCL JumpStart Guide" (PDF). Nvidia. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ '"ITC Garamond Font Family". MyFonts.com. Retrieved 2007-01-19.

- ^ Eggers, Dave. The Best of McSweeney's - Volume 1. ISBN 0-241-14234-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sloan, Robin. "Mister Penumbra's 24-hour bookstore. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. Print.

References

- Bringhurst, Robert (2012). The Elements of Typographic Style (4th ed.). Hartley & Marks. ISBN 978-0-88179-212-6.

- Carter, Rob; Day, Ben; Meggs, Philip (1993). Typographic Design: Form and Communication (2nd ed.). Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0-442-00759-0.

- Lawson, Alexander S. (1990). "10. Garamond". Anatomy of a Typeface. Godine. ISBN 978-0-87923-333-4.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Loxley, Simon (2004). The Secret History of Letters. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1850433972.

- Updike, Daniel Berkeley (1980) [1937]. Printing Types: Their History, Forms and Use. Dover. ISBN 0-486-23929-2.

External links

- Garamond at culture.fr

- Just what makes a “Garamond” a Garamond?

- Garamond v Garamond | Physiology of a typeface

- Illuminating Letters #1: Garamond

- Garamond at Typophile

- Garamond or Garamont?, Professor James Mosley

- Monotype Garamond at Microsoft Typography

- Adobe Garamond sample booklet

- Garamond No 8

- ATF Garamond poster

- EB Garamond, a free variant under the Open Font License

- EB Garamond download site