Cardiff Giant

The Cardiff Giant was one of the most famous archaeological hoaxes in American history. It was a 10-foot-tall (3.0 m), roughly 3,000 pound[1] purported "petrified man", uncovered on October 16, 1869 by workers digging a well behind the barn of William C. "Stub" Newell, in Cardiff, New York. He covered the giant with a tent and it soon became an attraction site.[1] Both it and an unauthorized copy made by P. T. Barnum are still being displayed. P.T. Barnum's is on display at Marvin's Marvelous Mechanical Museum in Farmington Hills, Michigan.

Creation and discovery

[edit]The giant was the creation of a New York tobacconist named George Hull. He was deeply attracted to science and especially to the theory of evolution proposed by Charles Darwin.[2] Hull got into an argument with Reverend Turk and his supporters at a Methodist revival meeting about Genesis 6:4, which states that there were giants who once lived on Earth.[3] Hull, a skeptic, being the minority party, lost the argument.[4] Angered by his defeat and the credulity of people, Hull wanted to prove how easily he could fool people with a fake giant.[5]

The idea of a petrified man did not originate with Hull, however. During 1858, the newspaper Alta California had published a fake letter claiming that a prospector had been petrified when he had drunk a liquid within a geode. Other newspapers had also published stories of supposedly petrified people.[6]

In 1868, Hull, accompanied by a man named H.B. Martin, hired men to quarry out a 10-foot-4.5-inch-long (3.2 m) block of gypsum in Fort Dodge, Iowa, telling them it was intended for a monument to Abraham Lincoln in New York. He shipped the block to Edward Burkhardt in Chicago, a German stonecutter. Burkhardt hired two sculptors named Henry Salle and Fred Mohrmann to create the giant. While it is not clear if Burkhardt was aware of Hull's intentions, it is reported that they took steps to cover up their work during the carving, putting up quilts to lessen the sound of carving.[2]

The giant was designed to imitate the form of Hull himself.[4] Hull consulted a geologist and learned that hairs wouldn't be petrified, so he removed the hair and beard from the giant.[2] The length of the giant was 10 feet 4½ inches and it weighed 2990 pounds.[7]

Various stains and acids were used to make the giant appear to be old and weathered. In order for the giant to look ancient, Hull first wiped the giant using a sponge soaked with sand and water. The giant's surface was beaten with steel knitting needles embedded in a board to simulate pores. The giant was also rubbed with sulphuric acid to create a deeper, vintage-like color. During November 1868, Hull transported the giant by railroad to the farm of his cousin, William Newell. By then, he had spent US$2,600 (equivalent to $60,000 in 2023) for the hoax.[2]

On a night in late November 1868, the giant was buried in a hole in Newell's farm.[2] Nearly a year later, Newell hired Gideon Emmons and Henry Nichols, ostensibly to dig a well, and on October 16, 1869, they found the giant.[8] One of the men reportedly exclaimed, "I declare, some old Indian has been buried here!"[6]

Exhibition and exposure as fraud

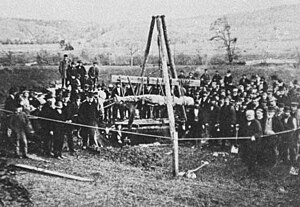

[edit]On the first day, visitors were able to view the giant with no fee charged. The next day, a tent was set up on the discovery site and Newell charged each visitor fifty cents for a fifteen-minute session of viewing the giant. The number of visitors went to about three to five hundred per day as the demand for wagons and carriages dramatically increased. The townspeople also gained huge profit because of the Cardiff Giant. The hotels and restaurants in Cardiff saw more customers in those four days than they had ever seen before.[2]

Some believed this giant was a petrified man, while some believed it was a statue. Those who believed it was a petrified man thought it was one of the giants mentioned in the aforementioned Genesis verse.[1] On the other hand, John F. Boynton, the first geologist to examine the giant, declared that it could not be a fossilized man, but hypothesized that it was a statue that was carved by a French Jesuit in the 16th or 17th century in order to impress the local Native Americans.[9]

Andrew D. White, the first president of Cornell University, made a close inspection of the Cardiff Giant. He noticed that there was no good reason to try to dig a well in the exact spot the giant had been found.

“Being asked my opinion, my answer was that the whole matter was undoubtedly a hoax; that there was no reason why the farmer should dig a well in the spot where the figure was found; that it was convenient neither to the house nor to the barn; that there was already a good spring and a stream of water running conveniently to both; that, as to the figure itself, it certainly could not have been carved by any prehistoric race, since no part of it showed the characteristics of any such early work; that, rude as it was, it betrayed the qualities of a modern performance of a low order.”

However, he was taken aback by the channels on the bottom part of the giant, stating that for such grooving to be created on local Onondaga grey limestone would require years.[10]

Yale paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh examined the statue, pointing out that it was made of soluble gypsum, which, had it been buried in its blanket of wet earth for centuries, would not still have fresh tool marks on it (which it did), and termed it "a most decided humbug".[11][12] Some theologians and preachers, however, defended its authenticity.[13]

Eventually, Hull sold his part-interest for $23,000 (equivalent to $554,000 in 2023) to a syndicate of five men headed by David Hannum. They moved it to Syracuse, New York, for exhibition. The giant drew such crowds that showman P. T. Barnum offered $50,000 for the giant. When the syndicate refused, he hired a man to model the giant's shape covertly in wax and create a plaster copy. He displayed his giant in New York, claiming that his was the real giant, and the Cardiff Giant was a fake.[6]

As the newspapers reported Barnum's version of the story, David Hannum was quoted as saying, "There's a sucker born every minute" in reference to spectators paying to see Barnum's giant.[14] Since then, the quotation has often been misattributed to Barnum himself.

Hannum sued Barnum for calling his giant a fake, but the judge told him to get his giant to swear on his own genuineness in court if he wanted a favorable injunction.[6]

On December 10, 1869, Hull confessed everything to the press,[15] and on February 2, 1870, both giants were revealed as fakes in court; the judge also ruled that Barnum could not be sued for terming a fake giant a fake.[16] Hull proclaimed that he did not confess because of the pressing criticism, but confessed proudly that he intended for the hoax to be exposed to reveal the tendency of the Christian community to believe in things too easily and to counter the fundamentalist belief that giants once roamed the earth.[4]

Subsequent and current resting places

[edit]The Cardiff Giant was displayed at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition, but did not attract much attention.[6]

Iowa publisher Gardner Cowles, Jr.,[17] bought it later to adorn his basement rumpus room as a coffee table and conversation piece. In 1947 he sold it to the Farmers' Museum in Cooperstown, New York, where it is still displayed.[18]

The owner of Marvin's Marvelous Mechanical Museum, a coin-operated game arcade and museum of oddities in Farmington Hills, Michigan, has said that the copy displayed there is Barnum's.[19][20]

A copy of the Giant is displayed at The Fort Museum and Frontier Village in Fort Dodge, Iowa.[21]

Imitators

[edit]The Cardiff Giant has inspired a number of similar hoaxes.

- In 1876, the Solid Muldoon was exhibited in Beulah, Colorado, at 50 cents a ticket. There was also a rumor that Barnum had offered to buy it for $20,000. One employer later revealed that this was also a creation of George Hull, aided by Willian Conant. The Solid Muldoon was made of clay, ground bones, meat, rock dust, and plaster.[22]

- In 1879, the owner of a hotel at what is now Taughannock Falls State Park hired men to create a fake petrified man and place it where workmen would dig it up. One of the men who had buried the giant later revealed the truth when drunk.[23][24]

- During 1897, a petrified man found downriver from Fort Benton, Montana, was claimed by promoters to be the remains of former territorial governor and U.S. Civil War General Thomas Francis Meagher. Meagher had drowned in the Missouri River during 1867. The petrified man was displayed across Montana as a novelty and exhibited in New York and Chicago.[25]

In popular culture

[edit]- In Halt and Catch Fire, the fictional Cardiff Giant personal computer was named after the petrified man.

- "Cardiff Giant" is a song on the 2012 album Ten Stories by the band mewithoutYou.

- Mark Twain's 1869 short story "The Legend of the Capitoline Venus" was inspired by the Cardiff Giant, and the ghost of the Giant is a character in Twain's 1870 short story "A Ghost Story."

- The Cardiff Giant was referenced in the 1935 short story "Out of the Aeons" by H.P. Lovecraft and Hazel Heald.

- J. Jonah Jameson writes that Spider-Man is the biggest hoax since the Cardiff Giant in The Amazing Spider-Man #18 (1964).

- The podcast The Memory Palace did an episode about the Cardiff Giant.

- A character called the Cardiff Giant appeared occasionally in the early years of the newspaper comic Alley Oop. He was larger than the other cavemen, had a pale beard, and spots over his torso and arms.

- The 1997 The Simpsons episode "Lisa the Skeptic" was inspired by the Cardiff Giant, the Piltdown Man, and the Scopes trial.

- The Cardiff Giant was referenced in the Babylon Five novel The Shadow Within by Jeanne Cavelos.

- Myron Edward Batesole was a professional wrestler during the 1940s and 50s billed as "The Cardiff Giant."

- Power-violence band Spazz used an image of The Cardiff Giant for their album “Dwarf Jester Rising”

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b c "This Month in History: The Cardiff Giant". Onondaga Historical Association. 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ a b c d e f Franco, Barbara (1969). "The Cardiff Giant: A Hundred Year Old Hoax". New York History. 50 (4): 420–440. ISSN 0146-437X. JSTOR 42677717.

- ^ Magnusson 2006, p. 188

- ^ a b c Pettit, Michael (2006). ""The Joy in Believing": The Cardiff Giant, Commercial Deceptions, and Styles of Observation in Gilded Age America". Isis. 97 (4): 659–677. doi:10.1086/509948. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 10.1086/509948. PMID 17367004. S2CID 25861933.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth L. (1995). Frauds, myths, and mysteries : science and pseudoscience in archaeology. Mayfield Pub. OCLC 604139167.

- ^ a b c d e Rose, Mark (November–December 2005), "When Giants Roamed the Earth", Archaeology, 58 (6), Archaeological Institute of America, archived from the original on December 17, 2009, retrieved April 26, 2005

- ^ Dunn, James Taylor (1948). "The Cardiff Giant Hoax". New York History. 29 (3): 367–377. ISSN 0146-437X. JSTOR 43460302.

- ^ "A Fossil Giant – Singular Discovery Near Syracuse". National Republican. Washington, D.C. October 20, 1869. p. 4. Retrieved January 29, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Stephen W. Sears, "The Giant in the Earth" Archived 2009-02-06 at the Wayback Machine, American Heritage Magazine, August 1975.

- ^ "The Cardiff Giant". www.lockhaven.edu. Retrieved 2022-03-22.

- ^ "The Onondaga Giant: Professor Marsh, of Yale College, Pronounces it a Humbug". New York Herald. December 1, 1869. p. 23. Retrieved January 29, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Plate, Robert. The Dinosaur Hunters: Othniel C. Marsh and Edward D. Cope, p. 77, David McKay Company, Inc., New York, New York, 1964.

- ^ Cardiff Giant, Geological Hall, Albany

- ^ "HistoryReference.org: P. T. Barnum Never Did Say "There's a Sucker Born Every Minute"". Archived from the original on 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ^ "An Alleged Revelation by Hull, the Giant Maker". Buffalo Express. December 13, 1869. p. 2. Retrieved January 29, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Smith, Gerald. "Fake of a Fake of a Fake: A giant tale of local lore". Press & Sun-Bulletin. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Letter to Paul M. Paine, dated August 28, 1939. OCLC 910726243.

- ^ "The Cardiff Giant". Farmer's Museum. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ Nicklell, Joe (May–June 2009), "Cardiff's Giant Hoax", Skeptical Inquirer, 33 (3)

- ^ "Marvin's Marvelous Mechanical Museum". RoadsideAmerica.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "The Fort Museum". Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Rose, Mark (November–December 2005). "When Giants Roamed the Earth". Archaeology. 58 (6). Archaeological Institute of America. Archived from the original on 2010-06-26. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Rogers, A. Glenn (1953). "The Taughannock Giant". No. Fall 2003. Life in the Finger Lakes. Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Githler, Charley (December 26, 2017). "A Look Back At: Home-Grown Hoax: The Taughannock Giant". Tompkins Weekly. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Kemmick, Ed. "'Petrified' man was big attraction in turn-of-the-last-century Montana" Archived 2016-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Billings Gazette, March 13, 2009

Bibliography

- Magnusson, Magnus (2006), Fakers, Forgers & Phoneys, Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, ISBN 1845961900

Further reading

- Jacobs, Harvey (1997), American Goliath, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0312194383

- Tribble, Scott (2009), A Colossal Hoax: The Giant From Cardiff that Fooled America, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0742560505