Graham Island (Mediterranean Sea)

Graham Island (also Graham Bank or Graham Shoal; Template:Lang-it) is a submerged volcanic island in the Mediterranean Sea. It was discovered when it last appeared on 1 August 1831 by Humphrey Fleming Senhouse, the captain of the first rate Royal Navy ship of the line St Vincent and named after Sir James Graham, the First Lord of the Admiralty. It was claimed by the United Kingdom. It forms part of the underwater volcano Empedocles, 30 km (19 mi) south of Sicily, and which is one of a number of submarine volcanoes known as the Campi Flegrei del Mar di Sicilia. Seamount eruptions have raised it above sea level several times before erosion submerged it again.

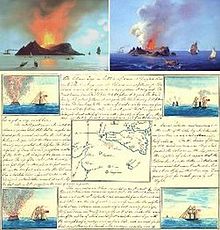

When it last rose above sea level after erupting in 1831, a four-way dispute over its sovereignty began, which was still unresolved when it disappeared beneath the waves again in early 1832. During its brief life, French geologist Constant Prévost was on hand, accompanied by an artist, to witness it in July 1831; he named it Île Julia, for its July appearance, and reported in the Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France.[5][6] Some observers at the time wondered if a chain of mountains would spring up, linking Sicily to Tunisia and thus upsetting the geopolitics of the region.[3] It showed signs of volcanic activity in 2000 and 2002, forecasting a possible appearance; however, as of 2016[update] it remains 6 m (20 ft) under sea level.

Early history

Graham Island lies in a volcanic area known as the Campi Flegrei del Mar di Sicilia (Phlegraean Fields of the Sea of Sicily), in between Sicily and Tunisia in the Mediterranean Sea. Many submarine volcanoes (seamounts) exist in the region, as well as some volcanic islands such as Pantelleria. Volcanic activity at Graham Island was first reported during the First Punic War, and the island has appeared and disappeared four or five times.[7] Several eruptions have been reported since the 17th century.[8]

1831 eruption and British possession

Graham Island's most recent appearance as an island was in July 1831. The first sign of an eruption was a period of high seismic activity spanning from 28 June to 10 July reported by the nearby town of Sciacca.[2] On July 4, an odor of sulfur spread through the town reportedly in such quantities that it blackened silver.[2] On 13 July, a column of smoke was clearly seen from St. Domenico. The residents believed it to be a ferry on fire.[2] On the same day, the brig Gustavo passed through the area, confirming a bubbling in the sea that the captain thought was a sea monster. Another ship reported dead fish floating in the water. By 17 July, a fully grown islet had formed.[2]

On 1 August 1831, Humphrey Fleming Senhouse, the captain of the first rate Royal Navy ship of the line HMS St Vincent claimed the Island for the British Crown and named it after Sir James Graham, the First Lord of the Admiralty. The eruptions of 1831 resulted in the island increasing in size to about 4 km (2.5 mi). However, it was composed of loose tephra, easily eroded by wave action, and when the eruptive episode ended it rapidly subsided, disappearing beneath the waves in January 1832, before the issue of its sovereignty could be resolved. Fresh eruptions in 1863 caused the island to reappear briefly before again sinking below sea level. At its maximum (in July and August 1831), it was 4,800 m (15,700 ft) in circumference and 63 m (207 ft) in height.[2] It sported two small lakes, the larger of which was 20 metres (66 ft) in circumference and 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in depth.[2]

Dispute

Graham Island was subject to a four-way dispute over its sovereignty, originally claimed for the United Kingdom and given the name Graham Island. The King of the Two Sicilies, Ferdinand II, after whom Sicilians named the island Ferdinandea, sent ships to the nascent island to claim it for the Bourbon crown. The French Navy also made a landing, and called the island Julia. Spain also declared its territorial ambitions.[3] Each wanted the island for its useful position in the Mediterranean trade route (to England and France) and its close position to Spain and Italy.[3]

Initial conflict

In August 1831, the volcano had risen to above sea level, although still only a couple of rocks, but the Royal Navy thought it was very suitable as a base to control the traffic in the Mediterranean, as it was closer to the European continent than the island of Malta. The small volcanic point was an important strategic point in the Mediterranean to the world's premier maritime power of the time, being closer to Spain and Italy than Malta, the next closest.[2] The British fleet landed, named it Graham Island, after Sir James Graham, the First Lord of the Admiralty, and planted their flag, the Union Jack.[1]

The King of Sicily also realized its strategic significance, and dispatched the corvette Etna to claim the new land and dub it Ferdinandea in honor of King Ferdinand II. Last on the scene was Constant Prévost, a co-founder of the French Geological Society, who compared the eruption to a bottle of champagne being uncorked. He named the island Julia, because it was born in July, and probably also in reference to France’s July Monarchy. Diplomatic disputes over the island’s status ensued.[1]

Extended conflict

For five months, conflict raged in newspapers and elsewhere as the different nations fought over a roughly 60-metre-high (200 ft) piece of basalt.[9] Tourists traveled to the island to see its two small lakes. Sailors watched it when passing by, and nobles of the House of Bourbon reportedly planned to set up a holiday resort on its beaches. None of these ideas came to fruition, however, as the island soon sank back beneath the waters. By 17 December 1831, officials reported no trace of it. As dynamically as the seamount appeared, it disappeared, defusing the conflict with it.[10]

Recent activity

After 1863, the volcano lay dormant for many decades, its summit just 8 m (26 ft) below sea level. In 2000, renewed seismic activity around Graham Island led volcanologists to speculate that a new eruptive episode could be imminent, and the seamount might once again become an island.[4] To forestall a renewal of the sovereignty disputes, Italian divers planted a flag on the top of the volcano in advance of its expected resurfacing.[10] To bolster their case, Sicilians, who call it Ferdinandea, summoned the descendant of the Bourbon King of Naples. In a ceremony filmed by a flotilla of camera crews, Prince Carlo di Bourbon lowered a plaque into the waves and told cheering locals: "It will always be Sicilian." Lobbied by fishermen and sailors, Ignazio Cucchiara, the mayor of Sciacca, invited Prince Carlo to attend the ceremony with his wife, The Duchess of Castro Camilla Crociani. To accommodate television crews the plaque was lowered well before reaching the shoal, which is a danger to shipping. Choppy waters forced divers to postpone the operation a week, until November 13, 2000.[4] The diving crew planted Sicily's flag, which features a Medusa's head surrounded by three naked legs – a sign traditionally interpreted as "keep away."

The marble plaque, weighing 150 kg (330 lb), was inscribed “This piece of land, once Ferdinandea, belonged and shall always belong to the Sicilian people."[3] The Prince told cheering locals: "It will always be Sicilian." But within six months, it had been fractured into twelve pieces, mostly likely by fishing gear but possibly by vandalism.[3][6]

In November 2002 the Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology in Rome observed minor seismic activity and gas emissions.[10] He put the time of resurfacing at a couple of weeks or months. Italian sailors put an Italian flag on the top of the bank to avoid other nations' claims if the island resurfaced. Despite showing signs in both 2000 and 2002, the seismicity did not lead to volcanic eruptions and as of 2006[update] Ferdinandea's summit remains about 8 metres (26 ft) below sea level.[1]

Significance

Scientific study

The sudden geologic phenomenon was observed and studied by numerous scientists. Among the Germans were Hoffmann, Schultz, and Philippi. Among the English were Edward Davy and Warington Wilkinson Smyth. Among the French was Constant Prévost. Among the Italians there was Scinà Domenico (1765-1837) who published his observations in the "Effeméridi Sicilians" (1832, vol. 2), and Carlo Gemmellaro (1787–1866), teacher of geology and mineralogy at Catania University, who published "Actions of the Gioenia Academy of Catania" (1831, vol.8).[2]

In 2006, further study revealed Graham Island to be just one part of the larger volcanic cone Empedocles.[7]

Marine significance

Graham Island is still referenced on marine charts, as its top is only 6 meters (20 feet) short of breaking the surface, much higher than the draft of most seafaring vessels.[9] It is also a small shoal on which near-surface maritime creatures dwell.

Coinage

In 2000, an unofficial minting of a penny was produced in Sicily, featuring the island on one side and, unusually, a bust of Elizabeth II on the other. (Italy, including Sicily, was using the lira by this time and the coin did not circulate.) David Mannucci, the designer of the coin, had the idea to make it after he "found out the existence of the ghost island" from a newspaper article. Besides the copper piece, varieties exist in silver, copper "with protective enamel", and in silver "with protective enamel". While this Italian-made coin fittingly bears the Italian name for the island, the conflicted piece also features a bust of “Elizabeth II D.G.R.” and bears a British denomination.[3]

In popular culture

During its emergence it was visited by Sir Walter Scott, and it provided inspiration for James Fenimore Cooper's The Crater, or Vulcan's Peak, Alexandre Dumas, père's The Speronara and Jules Verne's Captain Antifer and The Survivors of the Chancellor.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Bird, Maryann (20 March 2000). "Fire from the Sea". Time magazine. Accessed 4 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Ferdinandea - The Disappeared Isle". Almanacco Siciliano. Accessed 11 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ferdinandea". Chiefa Coins. Accessed 11 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Bourbons surface to retake island". The Guardian. Accessed 25 July 2016.

- ^ "Notes sur l’ile Julia pour servir a l’histoire de la formation des montagnes volcaniques" in Mémoires de la Soc. Géol. de France, 1835 ("L’exploration de île Julia" Archived 2006-05-01 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ a b "From out the azure main". London Geological Society. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- ^ a b Stewart, Phil (23 June 2006). "Scientists discover huge underwater volcano". Independent Online. Accessed 25 July 2016.

- ^ "Campi Flegrei Mar Sicilia". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ^ a b "Ferdinandea / Graham, Italy". Vulkaner. Accessed 10 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Volcano may emerge from the sea". BBC News. 26 November 2002. Accessed on 10 February 2009

External links

![]() Media related to Graham Island at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Graham Island at Wikimedia Commons