HMS Conqueror (1911)

Conqueror at anchor, 1912

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Conqueror |

| Namesake | A French ship, Conqueror, captured in 1745 |

| Builder | William Beardmore and Company, Dalmuir |

| Laid down | 5 April 1910 |

| Launched | 1 May 1911 |

| Commissioned | 23 November 1912 |

| Decommissioned | June 1922 |

| Out of service | June 1922 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 19 December 1922 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 21,922 long tons (22,274 t) (normal) |

| Length | 581 ft (177.1 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 88 ft 6 in (27.0 m) |

| Draught | 31 ft 3 in (9.5 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,730 nmi (12,460 km; 7,740 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 738–1,107 (1916) |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Conqueror was the third of four Template:Sclass- dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Navy in the early 1910s. She spent the bulk of her career assigned to the Home and Grand Fleets. Aside from participating in the failed attempt to intercept the German ships that had bombarded Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in late 1914, the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and the inconclusive Action of 19 August, her service during World War I generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea.

After the Grand Fleet was dissolved in early 1919, Conqueror was transferred back to the Home Fleet for a few months before she was assigned to the Reserve Fleet. The ship was sold for scrap in late 1922 and subsequently broken up.

Design and description

The Orion-class ships were designed in response to the beginning of the Anglo-German naval arms race and were much larger than their predecessors of the Template:Sclass- to accommodate larger, more powerful guns and heavier armour. In recognition of these improvements, the class was sometimes called "super-dreadnoughts". The ships had an overall length of 581 feet (177.1 m), a beam of 88 feet 6 inches (27.0 m) and a deep draught of 31 feet 3 inches (9.5 m). They displaced 21,922 long tons (22,274 t) at normal load and 25,596 long tons (26,007 t) at deep load as built; by 1918 Conqueror's deep displacement had increased to 28,430 long tons (28,890 t).[1] Her crew numbered 752 officers and ratings.[2]

The Orion class was powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each driving two shafts, using steam provided by eighteen Babcock & Wilcox boilers. The turbines were rated at 27,000 shaft horsepower (20,000 kW) and were intended to give the battleships a speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph).[3] During her sea trials on 7 June 1912, Conqueror reached a maximum speed of 22.1 knots (40.9 km/h; 25.4 mph) from 33,198 shp (24,756 kW). The ships carried enough coal and fuel oil to give them a range of 6,730 nautical miles (12,460 km; 7,740 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[4]

Armament and armour

The Orion class was equipped with 10 breech-loading (BL) 13.5-inch (343 mm) Mark V guns in five hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets, all on the centreline. The turrets were designated 'A', 'B', 'Q', 'X' and 'Y', from front to rear. Their secondary armament consisted of 16 BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mark VII guns. These guns were split evenly between the forward and aft superstructure, all in single mounts. Four 3-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) saluting guns were also carried. The ships were equipped with three 21-inch (533 mm) submerged torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and another in the stern, for which 20 torpedoes were provided.[1]

The Orions were protected by a waterline 12-inch (305 mm) armoured belt that extended between the end barbettes. Their decks ranged in thickness between 1 inch (25 mm) and 4 inches with the thickest portions protecting the steering gear in the stern. The main battery turret faces were 11 inches (279 mm) thick, and the turrets were supported by 10-inch-thick (254 mm) barbettes.[5]

Modifications

In 1914 the shelter-deck guns were enclosed in casemates. By October 1914, a pair of 3-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft (AA) guns had been added.[6] A fire-control director was installed on a platform below the spotting top before May 1915.[7] Additional deck armour was added after the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. Around the same time, three 4-inch guns were removed from the aft superstructure.[8] Two flying-off platforms were fitted aboard the ship during 1917–1918; these were mounted on 'B' and 'X' turret roofs and extended onto the gun barrels. A high-angle rangefinder was fitted in the forward superstructure by 1921.[9]

Construction and career

Conqueror, named after a French fire ship, Conqueror, that had been captured in 1745,[10] was the seventh ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy.[11] The ship was laid down by William Beardmore and Company at their shipyard in Dalmuir on 5 April 1910 and launched on 1 May 1911.[2] She was commissioned with a partial crew on 23 November 1912, but was not completed until March 1913, after which the remainder of her crew arrived.[12] Including her armament, her cost is variously quoted at £1,891,164[1] or £1,860,648.[3] The last of the four Orions to be completed, Conqueror and her sister ships comprised the Second Division of the 2nd Battle Squadron (BS) of the Home Fleet.[13]

World War I

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, Conqueror took part in a test mobilisation and fleet review as part of the British response to the July Crisis. Arriving in Portland on 25 July, she was ordered to proceed with the rest of the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow four days later[12] to safeguard the fleet from a possible surprise attack by the Imperial German Navy.[14] In August 1914, following the outbreak of World War I, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet, and placed under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe.[15] Repeated reports of submarines in Scapa Flow led Jellicoe to conclude that the defences there were inadequate and he ordered that the Grand Fleet be dispersed to other bases until the defences be reinforced. On 16 October the 2nd BS was sent to Loch na Keal on the western coast of Scotland. The squadron departed for gunnery practice off the northern coast of Ireland on the morning of 27 October and the dreadnought Audacious struck a mine, laid a few days earlier by the German auxiliary minelayer SS Berlin. Thinking that the ship had been torpedoed by a submarine, the other dreadnoughts were ordered away from the area, while smaller ships rendered assistance. On the evening of 22 November 1914, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea; Conqueror stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November.[16]

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans for a German attack on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby in mid-December using the four battlecruisers of Konteradmiral (Rear-Admiral) Franz von Hipper's I Scouting Group. The radio messages did not mention that the High Seas Fleet with fourteen dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts would reinforce Hipper. The ships of both sides departed their bases on 15 December, with the British intending to ambush the German ships on their return voyage. They mustered the six dreadnoughts of Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender's 2nd BS, including Conqueror and her sisters Orion and Monarch, and Beatty's four battlecruisers.[17]

The screening forces of each side blundered into each other during the early morning darkness of 16 December in heavy weather. The Germans got the better of the initial exchange of fire, severely damaging several British destroyers, but Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, commander of the High Seas Fleet, ordered his ships to turn away, concerned about the possibility of a massed attack by British destroyers in the dawn's light. A series of miscommunications and mistakes by the British allowed Hipper's ships to avoid an engagement with Beatty's forces.[18]

1915–1916

The Grand Fleet conducted another fruitless sweep of the North Sea in late December and, while trying to enter Scapa Flow in a Force 8 gale and minimal visibility, Monarch was accidentally rammed by Conqueror on 27 December. The former had to unexpectedly manoeuvre to avoid a guardship at the entrance and Conqueror could not avoid her. The latter ship's bow was badly damaged and she received temporary repairs at Scapa and Invergordon before proceeding to Devonport for full repairs, rejoining the Grand Fleet in March 1915.[19]

On 11 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off the Shetlands on 20–21 April. Jellicoe's ships swept the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June, the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of the Shetlands[20] and more training off the Shetlands beginning on 11 July. The 2nd BS conducted gunnery practice in the Moray Firth on 2 August and then returned to Scapa Flow. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, conducted another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, Conqueror participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November and repeated the exercise at the beginning of December.[21]

The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyers. On the night of 25 March, Conqueror and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale threatened the light craft, so the fleet was ordered to return to base. On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Imperial Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea.[22] The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft, but only arrived in the area after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet conducted another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.[23]

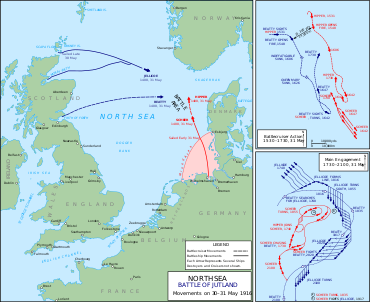

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Hipper's five battlecruisers. Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[24]

On 31 May, Conqueror, under the command of Captain Hugh Tothill, was the seventh ship from the head of the battle line after deployment.[25] The ship may have had engine problems during the battle because she was having trouble maintaining 20 knots as a signal from Jellicoe at 17:17[Note 1] instructed Thunderer to overtake Conqueror if she could not maintain speed. During the first stage of the general engagement, the ship fired three salvos from her main guns at one battleship at 18:31 without visible effect. She then shifted her fire to the crippled light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden, although the number of hits made, if any, is unknown. At 19:12, Conqueror fired her main guns at enemy destroyers without result and then again, at different destroyers at 19:25 with her aft turrets. This was the last time that the ship fired her guns during the battle, having expended a total of 57 twelve-inch shells (41 common pointed, capped and 16 armour-piercing, capped).[26]

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.[27]

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser SMS Moltke forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany.[28] The ship was present at Rosyth, Scotland, when the High Seas Fleet surrendered there on 21 November[29] and she remained part of the 2nd BS through 1 March 1919.[30]

By 1 May, Conqueror had been assigned to the 3rd BS of the Home Fleet.[31] On 1 November, the 3rd BS was disbanded and Conqueror was transferred to the Reserve Fleet at Portland, together with her sisters.[32] The ship was still in Portland as of 18 December 1920,[33] but was transferred to Portsmouth before June 1921 when she relieved Orion as the flagship of the Reserve Fleet there. Conqueror was listed for disposal in June 1922 in accordance with the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty. On 19 December the ship was sold for scrap to the Upnor Shipbreaking Co. and she arrived at Upnor on 30 January 1923 to begin demolition.[12]

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 136

- ^ a b Gardiner & Gray, p. 28

- ^ a b Parkes, p. 525

- ^ Burt, pp. 136, 139–40

- ^ Burt, pp. 134, 136, 139

- ^ Friedman, pp. 123, 199

- ^ Brooks, p. 168

- ^ Burt, p. 140

- ^ Burt, p. 142; Friedman, pp. 123, 198–200, 205

- ^ Silverstone, p. 223

- ^ Colledge, p. 76

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 150

- ^ Parkes, p. 528

- ^ Massie, p. 19

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 32

- ^ Goldrick, p. 156; Jellicoe, pp. 143–44, 148, 163–65

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 28–30

- ^ Goldrick, pp. 200–14

- ^ Burt, p. 150; Goldrick, p. 242

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 211–12, 217–19, 221–22

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 228, 234–35, 243, 246, 250, 253, 257–58

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 270–71, 275, 279–80, 284, 286

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 286–90

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Corbett, frontispiece map and p. 428

- ^ Campbell, pp. 118, 156–57, 205, 212, 346–47

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–32

- ^ Halpern, pp. 418–20

- ^ "Operation ZZ". The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 March 1919. p. 10. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 May 1919. p. 12. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "The Navy List" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 December 1919. pp. 694, 709. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 December 1920. pp. 709a-11. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. III (reprint of the 1940 second ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

- Friedman, Norman (2015). The British Battleship 1906–1946. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-225-7.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1985). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916 (repr. ed.). London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.