Hagia Sophia, Trabzon

41°00′12″N 39°41′46″E / 41.00333°N 39.69611°E

Hagia Sophia (Template:Lang-el, meaning "Holy Wisdom" Template:Lang-tr) is a formerly Greek Orthodox church which was converted into a mosque in 1584, and located in Trabzon, in the north-eastern part of Turkey. It was converted into a museum in 1964[1] and back into a mosque in 2013.[2] It dates back to the thirteenth century when Trabzon was the capital of the Empire of Trebizond. It is located near the seashore and two miles west of the medieval town's limits. It is one of a few dozen Byzantine sites extant in the area. It has been described as being "regarded as one of the finest examples of Byzantine architecture."[3]

History

Hagia Sophia was built in Trebizond during the reign of Manuel I between 1238 and 1263.[4] The oldest graffiti carved in the apses of the church contain the dates 1291 and 1293.[5] After Mehmed II conquered the city in 1461, the church was possibly converted into a mosque and its frescos covered in whitewash. Other scholars suggest it was not converted until 1584, being spared the initial transformation because it stood several kilometers outside the city walls. The adjacent monastery continued to be used by monks as late as 1701, when Tournefort found them still in residence. It is likely that the monks gradually abandoned a building that failed to protect them from harassment and predation, and the Turks assumed its use without needing to expel them.[6]

According to local tradition, at the turn of the 19th-century the site was used as a cholera hospital. During World War I the city was occupied by the Russian military and for the first time the church could be examined by archaeologists, including Fyodor Uspensky, and some preliminary cleaning of the wall paintings began. In the 1940s it was reported to be locked and used as a store, but by the 1950s it was again in use as a mosque.[7] In 1964, when it was turned into a museum.[1] Between 1958 and 1964 the surviving frescoes were uncovered and the church consolidated with the help of experts from the University of Edinburgh and the General Directorate of Foundations; one expert involved in the work estimated no more than one-sixth of the original decorations had survived.[8] All that did survive, however, are thought to be original works done just after its construction, and are considered part of the Byzantine 'Palaiologic Renaissance'.

The Hagia Sophia church is an important example of late Byzantine architecture, being characterised by a high central dome and four large column arches supporting the weight of the dome and ceiling. Below the dome is an Opus sectile pavement of multicolored stones. The church was built with a cross-in-square plan, but with an exterior form that takes the shape of a cross thanks to prominent north and south porches. The structure is 22 metres long, 11.6 metres wide and 12.7 metres tall. The late 13th-century frescos, revealed during the University of Edinburgh restoration, illustrate New Testament themes. External stone figurative reliefs and other ornamenting is in keeping with local traditions found in Armenia and Georgia. 24 metres to the west of the church is a tall bell tower, 40 metres high. It was built in 1427 and houses a small chapel on its second floor. The internal walls of the bell tower are covered in frescoes. It was also used as an observatory by local astronomers.

Mosque conversion

In 2012, the religious authorities (Diyanet) filed a lawsuit against the ministry of culture, claiming the ministry had been 'illegally occupying' the church for some decades. The Diyanet won the case and received the ownership of the building. On 5 July 2013, the former church was partially converted for a while into a mosque according to the local Vakif Direction of Trabzon, which is the owner of the estate. The reconstruction works were started,[9][10] in which some frescoes were veiled and the floor covered by a carpet. The mufti of the Turkish province Trabzon said that “the works for opening the Hagia Sophia mosque in the city to practice prayers again are going on,” and claimed that “during the prayer the mural paintings will be covered by curtains". The local union of architects from Trabzon filed a lawsuit against the ministry of religious affairs' conversion plan. A local judge ruled the transformation of the former church to be illegal, and ordered it to be maintained as a museum.[11] However, it has remained a mosque. Between 2013 and 2018 the fresco's and opus sectile floor mosaic in the prayer hall were covered by immovable curtains and carpets, while the fresco's in the narthex remained uncovered. During renovation works from 2018 to 2020 the building was closed to visitors. A report drafted by the local union of architects heavily criticized the 2013 mosque conversion, and a court ordered the ministry of religious affairs to fulfill its promise and make the frescoes visible outside prayer time. In 2020 a retractable suspended ceiling was put in place underneath the dome, and a glass floor was placed over the opus sectile mosaic.

Cultural significance

The church figures prominently and has key significance for the lead character's spiritual development in Rose Macaulay's novel The Towers of Trebizond. "It took me some time to make out the Greek inscription, which was about saving me from my sins, and I hesitated to say this prayer, as I really did not want to be saved from my sins, not for the time being, it would make things too difficult and too sad."

Gallery

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Exterior south side

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Decoration exterior

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Decoration exterior

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Decoration exterior

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Capital

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Exterior

-

Interior

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Evangelists' fresco most of it

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Evangelists' fresco centre

-

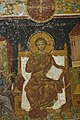

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Evangelists' fresco Mark closer up

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Evangelists' fresco Matthew

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Evangelists' fresco John close up

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Evangelists' fresco Luke

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Several scenes

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Marriage in Kanaa

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Marriage in Kanaa detail

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Christ teaching in the temple

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Christ teaching in the temple detail

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Feeding of the thousands

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Feeding of the thousands detail

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Feeding of the thousands detail

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Feeding of the thousands detail

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Healing of the blind man at the pool of Siloam

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified fresco

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified scene

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified scene

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Mary and Christ

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Mary and Christ detail with Christ

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Interior

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Descent into hell

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Baptism of Christ

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Baptism of Christ

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Interior

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Last supper

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified scene

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia St. Bartholomew

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified scene

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified scene

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Unidentified scene

-

Trabzon Hagia Sophia Baptism of Christ

-

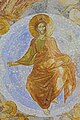

Dome frescoes

-

Floor in 2008

-

Reconstruction of the Opus Sectile floor tiling as drawn by Charles Texier in 1864. What remains was covered with a carpet in 2013.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Eden, Caroline (2017-10-25). "Turkey's other Hagia Sophia, in Trabzon". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-10-26.

- ^ "Restoration of the Church of Saint Sophia at Trabzon | Research at the BIAA | BIAA". biaa.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ^ "Religion in Turkey: Erasing the Christian past." The Economist. July 25, 2013.

- ^ Eastmond, Anthony. "The Byzantine Empires in the Thirteenth Century" in Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004, p. 1.

- ^ Gabriel Millet, "Les monastères et les églises de Trébizonde", Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, 19 (1895), p. 428

- ^ Millet, Les monastères, p. 433

- ^ David Talbot Rice, "The Church of Haghia Sophia at Trebizond", p6.

- ^ Some details of the preservation can be read in David Winfield, "Sancta Sophia, Trebizond: A Note on the Cleaning and Conservation Work", Studies in Conservation, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Nov., 1963), pp. 117-130.

- ^ "Mosque conversion raises alarm."

- ^ "Bartholomew I: Do not transform Hagia Sophia in Trabzon into a mosque."

- ^ Hagia Sophia to remain museum Kerknet, 6 November 2013

Further reading

- Eastmond, Anthony. Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium: Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004.

External links

- Hagia Sophia of Trabzon/Trebizond

- The Church of Hagia Sophia, Trabzon

- Photos of the Hagia Sophia in Trabzon

- The Church of Hagia Sophia at Trapezounta, Pontos by Dr Constantine Hionides

- Buildings and structures completed in 1263

- Byzantine museums in Turkey

- Byzantine church buildings in Turkey

- Byzantine art

- Empire of Trebizond

- Museums established in 1964

- Byzantine architecture in Trabzon

- Greek Orthodox churches in Turkey

- Cathedrals in Turkey

- Mosques converted from churches in the Ottoman Empire

- Museums in Trabzon Province

- Greek Orthodox cathedrals

- Pontic Greek culture