Hatfield–McCoy feud

| Hatfield-McCoy feud | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Hatfield–McCoy feud site along the Tug Fork tributary (right) in the Big Sandy River watershed | |||

| Date | 1863–1891 | ||

| Location | Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River, West Virginia–Kentucky | ||

| Caused by | American Civil War, land disputes, revenge killings | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

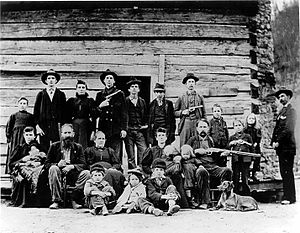

The Hatfield–McCoy feud (1863–1891) involved two families of the West Virginia–Kentucky area along the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River. The Hatfields of West Virginia were led by William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield while the McCoys of Kentucky were under the leadership of Randolph "Ole Ran'l" McCoy. Those involved in the feud were descended from Ephraim Hatfield (born c. 1765) and William McCoy (born c. 1750). The feud has entered the American folklore lexicon as a metonym for any bitterly feuding rival parties. More than a century later, the feud has become synonymous with the perils of family honor, justice, and revenge.

William McCoy, the patriarch of the McCoys, was born in Ireland around 1750 and many of his ancestors hailed from Scotland.[1] The family, led by grandson Randolph McCoy, lived mostly on the Kentucky side of Tug Fork (a tributary of the Big Sandy River). Of English origin,[2] the Hatfields, led by William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield, son of Ephraim and Nancy (Vance) Hatfield, lived mostly on the West Virginia side. The majority of the Hatfields living in Mingo County (then part of Logan County), West Virginia fought for the Confederacy in the American Civil War; most McCoys, living in Pike County, Kentucky, also fought for the Confederacy; with the exception of Asa Harmon McCoy, who fought for the Union. The first real violence in the feud was the death of Asa Harmon McCoy as he returned from the war, murdered by a group of ex-Confederate Homeguards called the Logan Wildcats. Devil Anse Hatfield was a suspect at first, but was later confirmed to have been sick at home at the time of the murder. It was widely believed that his uncle, Jim Vance, a member of the Wildcats, committed the murder.[3]

The Hatfields were more affluent than the McCoys and were well-connected politically. Devil Anse Hatfield's timbering operation was a source of wealth for his family, but he employed many non-Hatfields, and even hired McCoy family members Albert McCoy, Lorenzo Dow McCoy, and Selkirk McCoy.

Feud

Asa Harmon McCoy, who was killed by rebel forces according to his pension statement, was discharged from the army early because of a broken leg. He returned home to a warning from James "Jim" Vance (folklore) - a relative of the Hatfield family - that Harmon could expect a visit from the County Wildcats, a local militia group with members from the Hatfield family including Devil Anse. James Vance however was never on the civil war roster for the Logan Wild Cats. Frightened by gunshots as he drew water from his well, Harmon hid in a nearby cave, supplied with food and necessities each day by his slave, Pete, but the Wildcats followed Pete's tracks in the snow, discovered Harmon, and fatally shot him on January 7, 1865.[4]

At first, Devil Anse was suspected, but later, after he was confirmed to have been confined to his bed, suspicion of guilt focused squarely on Vance. However, in an era when Harmon's military service was widely considered by many of the region's inhabitants to be in and of itself an act of disloyalty, even Harmon's own family believed that he had brought his murder upon himself.[citation needed]Actually the Commonwealth of Kentucky had declared for the United States after being invaded by Confederate forces - so Harmon's service in the Union army was consistent with the policy of the State in which he lived. Eventually, the case withered, and no suspect was brought to trial. Historians now believe that this did not set off the feud but is an act segregated from it.[4][better source needed]

The second recorded instance of violence in the feud occurred thirteen years later, in 1878, after a dispute about the ownership of a hog: Floyd Hatfield, a cousin of Devil Anse's, had the hog, but Randolph McCoy claimed it was his,[5] saying that the "notches" (markings) on the pig's ears were McCoy, not Hatfield, marks. The matter was taken to the local Justice of the Peace, Anderson "Preacher Anse" Hatfield,[6] who ruled for the Hatfields by the testimony of Bill Staten, a relative of both families. In June 1880, Staten was killed by two McCoy brothers, Sam and Paris, later acquitted on the grounds of self-defense.

The feud escalated after Roseanna McCoy entered a relationship (courtship) with Devil Anse Hatfield's son Johnson, known as "Johnse" (spelled "Jonce" in some sources), leaving her family to live with the Hatfields in West Virginia. Roseanna eventually returned to the McCoys, but when the couple tried to resume their relationship, Johnse Hatfield was arrested by the McCoys on outstanding Kentucky bootlegging warrants. He was freed from McCoy custody only when Roseanna made a desperate midnight ride to alert Devil Anse, who organized a rescue party. The Hatfield party surrounded the McCoys and took Johnse back to West Virginia before he could be transported the next day to the county seat in Pikeville, Kentucky. Despite what was seen as a betrayal of her family on his behalf, Johnse Hatfield thereafter abandoned the pregnant Roseanna for her cousin, Nancy McCoy, whom he wed in 1881.

The feud continued in 1882 when Ellison Hatfield, brother of Devil Anse, was killed by three of Roseanna McCoy's younger brothers: Tolbert, Pharmer, and Bud. During an election day in Kentucky, the three McCoy brothers fought a drunken Ellison and his other brother; Ellison was stabbed 26 times and finished off with a gunshot. The McCoy brothers were initially arrested by Hatfield constables and were taken to Pikeville for trial. Secretly, Devil Anse Hatfield organized a large group of followers and intercepted the constables and their McCoy prisoners before they reached Pikeville. The brothers were taken by force to West Virginia, to await the fate of mortally wounded Ellison Hatfield and when Ellison died from his injuries, the McCoy brothers were killed by the Hatfields' vigilante justice in turn: being tied to pawpaw bushes, where each was shot numerous times with a total of 50 shots fired. Their bodies were described as "bullet-riddled".[7]

Even though the Hatfields and most inhabitants of the area believed their revenge was warranted, up to about twenty men, including Devil Anse, were indicted. All of the Hatfields eluded arrest; this angered the McCoy family, who took their cause up with Perry Cline. Cline was married to Martha McCoy. Historians believe that Cline used his political connections to reinstate the charges and announced rewards for the Hatfields' arrest as an act of revenge. A few years prior, Cline lost a lawsuit against Devil Anse over the deed to thousands of acres of land, subsequently increasing the hatred between the two families.

The feud reached its peak during the 1888 New Year's Night Massacre. Several members of the Hatfield clan surrounded the McCoy cabin and opened fire on the sleeping family. The cabin was set on fire in an effort to drive Randolph McCoy into the open. He escaped by making a break for it but two of his children were shot, and his wife was beaten and left for dead. The remaining McCoys moved to Pikeville to escape the West Virginia raiding parties.

Between 1880 and 1891, the feud claimed more than a dozen members of the two families. On one occasion, the Governor of West Virginia even threatened to have his militia invade Kentucky. In response, Kentucky Governor S. B. Buckner sent his Adjutant General Sam Hill[8] to Pike County to investigate the situation. Nearly a dozen people died and at least 10 people were wounded.[9]

In 1888, Wall Hatfield and eight others were arrested by a posse led by Frank Phillips and brought to Kentucky to stand trial for the murder of Alifair McCoy, killed during the New Year's Massacre.[10] She had been shot after exiting the burning house. Because of issues of due process and illegal extradition, the United States Supreme Court became involved (Mahon v. Justice, 127 U.S. 700 (1888)).[11] The Supreme Court ruled 7–2 in favor of Kentucky, holding that, even if a fugitive is returned from the asylum state illegally, instead of through lawful extradition procedure, no federal law prevents him from being tried. Eventually, the men were tried in Kentucky and all were found guilty. Seven received life imprisonment, while the eighth, Ellison "Cottontop" Mounts, was executed by hanging.[12] Thousands attended the hanging in Pikeville.

- Valentine "Uncle Wall" Hatfield, elder brother of Devil Anse, was overshadowed by Devil Anse's ambitions but was one of the eight convicted, dying in prison of unknown causes. He petitioned his brothers to assist in his emancipation from jail but none came for fear of being captured and brought to trial. He was buried in the prison cemetery, which has since been paved over.

- William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield, the younger and more militant brother of Valentine Hatfield, led the clan in most of their combative endeavors.

- Doc D. Mahon, son-in-law of Valentine and brother of Pliant, one of the eight Hatfields convicted, served 14 years in prison before returning home to live with his son, Melvin.

- Pliant Mahon, son-in-law of Valentine and brother of Doc,[clarification needed] served 14 years in prison before returning home to rejoin his ex-wife, who had remarried but left her second husband to live with Pliant again.

Fighting between the families eased following the hanging of Mounts. Trials continued for years until the 1901 trial of Johnse Hatfield, the last of the feud trials.

Deaths

- January 7, 1865: Former Union soldier Asa Harmon McCoy, probably by the "Logan Wildcats" led by Jim Vance.[13] *1

- 1878: Bill Staten (Hatfield family), as revenge for testifying on behalf of Floyd Hatfield in his trial for stealing a McCoy hog.[14] Shot by Sam McCoy, nephew of Randolph McCoy Sr.[15] *2

- August 9, 1882: Ellison Hatfield, injured in a fight with Tolbert, Pharmer, and Randolph McCoy, Jr. on August 7, dying two days later.[16] *3

- August 9, 1882: Tolbert McCoy, tied to pawpaw trees and killed as revenge for Ellison Hatfield's shooting/stabbing, on the day Ellison died. *4

- August 9, 1882: Pharmer McCoy, tied to pawpaw trees and killed as revenge for Ellison Hatfield's shooting/stabbing. *4

- August 9, 1882: Randolph McCoy Jr., tied to pawpaw trees and killed as revenge for Ellison Hatfield's shooting/stabbing.[17] *4

- 1886: Jefferson "Jeff" McCoy, following his murder of mail carrier Fred Wolford[18] shot by "Cap" Hatfield[15] *5

- January 1, 1888: Calvin McCoy, at Randolph's house by nine attackers led by Jim Vance. The attackers failed in their attempt to eliminate witnesses against them.[19] *6

- January 1, 1888: Alifair McCoy, at Randolph's house by Ellison Mounts.

- January 7, 1888: Jim Vance, killed by Frank Phillips.[15]

- January 18, 1888: Deputy Bill Dempsey, wounded by Jim McCoy and killed by Frank Phillips in Battle of Grapevine Creek[20]

- February 18, 1890: Ellison Mounts, hanged[21] for Alifair's murder.[12]

Numbers after asterisks (*) are cross references to names on the family trees below.

Hatfields and McCoys in the modern era

In 1979, the families united for a special week's taping of the popular game show Family Feud, in which they played for a cash prize and a pig which was kept on stage during the games.[22] The McCoy family won the week-long series three games to two. While the Hatfield family won more money – $11,272 to the McCoys' $8,459—the decision was made to augment the McCoy family's winnings to $11,273.[23]

Tourists travel to parts of West Virginia and Kentucky each year to see the areas and historic relics which remain from the days of the feud. In 1999, a large project known as the "Hatfield and McCoy Historic Site Restoration" was completed, funded by a federal grant from the Small Business Administration. Many improvements to various feud sites were completed. A committee of local historians spent months researching reams of information to find out about the factual history of the events surrounding the feud. This research was compiled in an audio compact disc, the Hatfield–McCoy Feud Driving Tour. The CD is a self-guided driving tour of the restored feud sites and includes maps and pictures as well as the audio CD (see external link below).

The Hatfield McCoy Feud Tour App for the iPhone, iPad and android devices has been developed by descendants of the Hatfields and McCoys. Tourists use the app to locate the sites and learn more about the feud. The program includes the locations of the major sites, shows the locations on GPS maps, includes historical information, photographs and historical documents related to the feud.[24]

Great-great-great grandsons of feud patriarch Randolph McCoy, Bo McCoy of Waycross, Georgia, and his cousin, Ron McCoy of Durham, North Carolina, organized a historic joint family reunion of the Hatfield and McCoy families in 2000. More than 5,000 people attended the reunion, which attained national attention.[25]

In 2002, Bo and Ron McCoy brought a lawsuit to acquire access to the McCoy Cemetery which holds the graves of six family members, including five slain during the feud. The McCoys took on a private property owner, John Vance, who had restricted access to the cemetery.[26] While the McCoys claimed victory in the suit, as of 2003 the cemetery was still not open to the general public.[citation needed]

In the 2000s, a 500-mile (800 km) all-terrain vehicle trail system, the Hatfield–McCoy Trails, was created around the theme of the feud.[27]

On June 14, 2003 in Pikeville, Kentucky, the McCoy cousins partnered with Reo Hatfield of Waynesboro, Virginia, to declare an official truce between the families. Reo Hatfield said that he wanted to show that if the two families could reach an accord, others could also. He had said that he wanted to send a broader message to the world that when national security is at risk, Americans put their differences aside and stand united: "We're not saying you don't have to fight because sometimes you do have to fight," he said. "But you don't have to fight forever." Signed by more than sixty descendants during the fourth Hatfield-McCoy Festival, the truce was touted as a proclamation of peace, saying "We ask by God's grace and love that we be forever remembered as those that bound together the hearts of two families to form a family of freedom in America." Governor Paul E. Patton of Kentucky and Governor Bob Wise of West Virginia signed proclamations declaring June 14 Hatfield and McCoy Reconciliation Day. Ron McCoy, one of the festival's founders, said it is unknown where the three signed proclamations will be exhibited. "The Hatfields and McCoys symbolize violence and feuding and fighting, but by signing this, hopefully people will realize that's not the final chapter," he said.

In 2011, the Hatfields and McCoys Dinner Show, a musical comedy production, opened in the resort community of Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, near the entrance to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The dinner show is held at 8 p.m. daily. During peak tourist seasons there is also a 2 p.m. lunch program.

The Hatfield and McCoy Reunion Festival and Marathon are held annually in June on a three-day weekend. The events take place in Pikeville, Kentucky., Matewan, West Virginia, and Williamson, West Virginia. The festival commemorates the famed feud and includes a marathon and half-marathon (the motto is "no feudin', just runnin'"), in addition to an ATV ride in all three towns. There is also a tug-of-war across the Tug Fork tributary near which the feuding families lived, a live re-enactment of scenes from their most famous fight, a motorcycle ride, live entertainment, Hatfield-McCoy landmark tours, a cornbread contest, pancake breakfast, arts, crafts, and dancing. Launched in 2000, the festival typically attracts thousands with more than 300 runners taking part in the races.[28]

In August 2015 members of both families helped archeologists dig for ruins at a site where they believe Randolph McCoy's house was burned. [29]

Media

Film

The 1923 Buster Keaton comedy Our Hospitality centers on the "Canfield–McKay feud," a thinly disguised fictional version of the Hatfield–McCoy feud.[30]

The 1939 Max Fleischer cartoon Musical Mountaineers has Betty Boop wander into the territory of the Peters family who are at war with the Hatfields.

The 1946 Disney cartoon short, The Martins and the Coys in Make Mine Music animated feature was another very thinly disguised caricature of the Hatfield–McCoy feud.[31]

In 1949, the Samuel Goldwyn feature film Roseanna McCoy told the story of the romance between the title character, played by Joan Evans, and Johnse Hatfield, played by Farley Granger.[32]

The 1949 Screen Songs short "Comin' Round the Mountain" features another thinly disguised caricature of the Hatfield–McCoy feud, with cats (called "Catfields") and dogs ("McHounds") fighting each other, until a new school teacher arrives.[33]

In 1950, Warner Bros. released a Merrie Melodies spoof of the Hatfield–McCoy feud titled "Hillbilly Hare", featuring Bugs Bunny interacting with members of the "Martin family", obviously a reference to a family in the other famous Kentucky feud, the Rowan County War who had been feuding with the "Coy family". When Bugs Bunny is asked, "Be y'all a Martin or be y'all a Coy rabbit?", Bugs answers, "Well, my friends say I'm very coy!" and laughs. The Martin brothers chase Bugs for the rest of the short and are outwitted by him at every turn.[34]

The 1951 Abbott and Costello feature Comin' Round the Mountain features a feud between the Winfields and McCoys.[35]

A 1975 television movie titled The Hatfields and the McCoys told a fictionalized version of the story. It starred Jack Palance as "Devil Anse" Hatfield and Steve Forrest as "Randall" McCoy.[36]

The two feuding Virginia families in the 2007 made-for-TV film Pumpkinhead: Blood Feud are called Hatfield and McCoy.[37]

In 2012, Lionsgate Films released a direct-to-DVD film titled Hatfields & McCoys: Bad Blood, starring Jeff Fahey, Perry King, and Christian Slater.[38]

Literature

Ann Rinaldi authored an historical novel titled The Coffin Quilt, based on a fictionalized account of the feud.[39]

There is a similar feud in Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In the novel, Huck finds himself in the middle of a feud between the Shepherdson and Grangerford families. Twain places this fictional analog in Arkansas, a few decades prior to the historical feud.[40]

Manly Wade Wellman's short story "Old Devlins Was A-Waitin'" has the protagonist calling up the shade of "Old Devlins" to settle a conflict on behalf of one of the latter's descendants, although the story takes some liberties with history.

Television

The Flintstones featured a feud between the Hatrocks and the Flintstones in the episode "The Flintstone Hillbillies" (aired January 16, 1964), which was loosely based upon the Hatfield–McCoy feud.[41]

The Andy Griffith Show also alluded to the rivalry in an episode called "A Feud is a Feud" (aired December 5, 1960), in which the feud is between the Wakefields and Carters.[42]

The 1968 Merrie Melodies cartoon "Feud with a Dude" has the character Merlin the Magic Mouse trying to make peace with the two families, only to end up as the new target. This short has Hatfield claiming McCoy stole his hen, while McCoy claims Hatfield stole his pig.[43]

Star Trek's Dr. Leonard McCoy ("Bones") is supposedly a distant descendant of the McCoy clan.[44]

The Hatfield–McCoy feud is said to be the inspiration for a long-running game show, Family Feud, and the Hatfields and McCoys actually appeared on the show in 1979.[45]

The second-season episode Vanished of NCIS takes place in a rural valley in Virginia, the two sides of which are feuding in a manner that Leroy Jethro Gibbs compares to the Hatfields and McCoys.

From May 28–30, 2012, U.S. television network The History Channel aired a three-part miniseries titled Hatfields & McCoys,[46] starring Kevin Costner as William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield and co-starring Bill Paxton as Randolph "Ole Ran'l" McCoy, Tom Berenger as Jim Vance, and Powers Boothe as Judge Valentine "Wall" Hatfield.[47][48] The miniseries set the record as the most-watched entertainment telecast in the history of advertising-supported basic cable.[49]

In 2013, NBC commissioned a pilot for a television show updating the feud to present-day Pittsburgh with Rebecca De Mornay, Virginia Madsen, Sophia Bush, and James Remar[50] but it was not picked up.[51]

On August 1, 2013, the reality television series Hatfields & McCoys: White Lightning premiered on the History channel. The series begins with an investor offering to set up the feuding families into business making moonshine, and follows the families' attempt to run the business together.[52]

In an episode of Modern Family originally aired January 15, 2014, titled "Under Pressure," Cam is working as a gym teacher who has plans to let parents play dodgeball with each other at the school's open house, and wants to divide the two teams into Hatfields and McCoys. The school principal frowns upon this idea, however, Gloria and a competitive mother played by Jane Krakowski decide to settle their score with such a game. Hurriedly Cam proclaims Hatfields for one side and McCoys for the other.[53]

In My Little Pony a future episode is to be named "The Hooffields and McColts"

In the WWE, the rivalry between Dean Ambrose and Roman Reigns and The Wyatt Family is often compared to the Hatfield-McCoy rivalry.

Role playing games

In World of Warcraft, the Alliance starting zone of Elwynn Forest features two feuding farmer families called the McClure and the Stonefield and a pig they are fighting over, a reference to the Hatfield–McCoy feud.

Music

"The Legend of Bad Jim" is a song by the rock band Majungas and it's dedicated to Jim Vance and his influence in the Hatfield/McCoy rivalry. [54][55]

The song "Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)" written by Bobby Emmons and Chips Moman, sung by Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, makes mention of the Hatfield/McCoy feud.

Hatfield genealogy

Devil Anse Hatfield family tree

To view, click on the righthand side of the bar below.

Names in red indicate those who were killed as a direct result of the feud.[56]

Names in orange highlight intermarriages between Hatfield and McCoy.

Numbers in green square brackets [ ] are cross references to the timeline in the "Deaths" section above

| with Mary | with Anna | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ephraim Hatfield b. c1765 m. Mary Smith Goff m. Anna M. Musick Bundy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valentine b. 1789 m. Martha Weddington | George b. 1804 m. Nancy Whitt | Jeremiah b. 1805 m. Rachel Vance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ephraim (Big Eaf) b. 1811 m. Nancy Vance (sister of Jim Vance) | Anderson (Preacher) b. 1835 m. Polly Runyan | Basil (Deacon) b. 1839 m. Nancy Lowe | Elias (Bad 'Lias) b. 1853 m. Jane Chafin | Floyd b. 1858 m. Anne Pinson m. Jenny Hunt | Ephraim b. 1838 m. Elizabeth McCoy | Jacob b. 1843/45 m. Rebecca Crabtree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valentine (Uncle Wall) b. 1834 m. Jane Maynard | Martha b. 1838 | Anderson (Devil Anse) b. 1839 m. Levicy Chafin | *Ellison[3] b. c1842 m. Sarah Staton | Elias (Good 'Lias) b. 1848 m. Elizabeth Chafin | William Sidney (Two-Gun Sid) b. 1891/93 m. Jessie Lee Testerman (née Maynard) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Victoria b. 1862 m. Plyant Mahon | Ellison Mounts[12] | Dr. Henry D. b. 1875 m. South Carolina Bronson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Johnson (Johnse) b. 1862 m. Nancy McCoy m. Rebecca Browning m. Roxie Browning m. Nettie Toler | Wm. Anderson (Cap) b. 1864 m. Nancy Glenn | Robt E. Lee b. 1867 m. Mariah Wolford | Nancy b. 1869 m. John Vance m. Charlie Mullens | Elliott Rutherford b. 1872 m. Margaret Shindler | Mary b. 1873 m. Frank Howes | Elizabeth b. 1875 m. John Caldwell | Elias b. 1878 m. Peggy Simple | Detroit (Troy) b. 1881 m. Pearl | Joseph b. 1883 m. Grace Ferrell | Rosada b. 1885 m. Marion Browning | Willis Wilson b. 1888 m. Lakie Maynor m. Ida Chafin | Tennyson (Tennis) b. 1890 m. Lettie Hunter m. Sadie Walters m. Margaret | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

McCoy genealogy

Randolph McCoy family tree

To view, click on the righthand side of the bar below.

Names in red indicate those who were killed as a direct result of the feud.

Names in orange highlight intermarriages between Hatfield and McCoy.

Numbers in green square brackets [ ] are cross-references to the timeline in the "Deaths" section above.[56][57]

b. c1750 Samuel

b. c1782

m. Elizabeth (Davis?)Daniel

b. 1790

m. Margaret TaylorJohn

b. 1788

m. Margaret Jackson Asa

b. c1810

m. Eleanor BurressWilliam

b. c1811

m. Mary BuressAllen

b. c1823

m. Betty BlankenshipSarah "Sally"

b. 1829

m. 1st cousin

RandolphRandolph

b. 1825

m. 1st cousin

Sarah "Sally"*Asa Harmon[1]

b. c1828

m. Martha KlineNancy

b. c1809

m. Wm Staton Selkirk

b. c1830

m.Louisa WilliamsonElizabeth

b. c1838

m. Ephraim HatfieldMary M

b. 1851

m. Bill DanielsJacob

b. 1853

m. Elizabeth Vance

m. Ruth ChristianLarkin

b. 1856-d.1937

m. Mary Coleman. *Louis Jefferson[5]

(Jeff)

b. 1859-d.1886Asa H

(Bud)

b. c1862Nancy

b. c1865

m. Johnse Hatfield

m. Frank PhillipsSarah

b. c1844

m. *Ellison[3] Hatfield*William Staton[2]

b. c1852 Lorenzo Dow

b. c1852

m. PhoebeFrank McCoy

1889–1969

m. America Hatfield

1893–1960

(granddaughter of *Ellison[3] Hatfield)Elliott Hatfield

1866–1939

m.Mathilda Christian

(parents of America Hatfield, who m. Frank McCoy) Josephine

b. c1850James H.

(Uncle Jim)

b. c1851

m. Malissa SmithFloyd

b. 1853

m. Mary Rutherford*Tolbert[4]

b. 1854

m. Mary ButcherSamuel

b. 1855

m. Martha JacksonLilburn

b. c1856Mary Katherine

b. 1857*Alifair[6]

b. 1858Roseanna

b. 1859Calvin[6]

b. c1862*Pharmer[4]

b. c1863*Randolph Jr.[4]

b. c1864William

b. c1866Trinvilla

b. c1868

m. William ThompsonAdelaide

b. 1870Fanny

b. 1873

m. Roland Charles

See also

References

- ^ "McCoy Family Genealogy". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "From Roots to Nuts: HATFIELD Thomas, I". Genfan.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Pearce p. 59–60.

- ^ a b History.com. "The Hatfield and McCoy Feud". Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ "Hatfield-McCoy Feud, Beckley Post-Herald August 7, 1957". Wvculture.org. August 7, 1957. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Anderson "Preacher Anse" Hatfield". Ghat.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Rice, p. 26.

- ^ Hill, Samuel E., Adjutant General of Kentucky: 1887–1891. "What in Sam Hill ... started the Hatfield and McCoy Feud? Report from the Adjutant General of Kentucky, 1888". National Guard History eMuseum. Kentucky.gov. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Current Opinion.p.417 list of killed/wounded. Books.google.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Rice p. 70.

- ^ "Mahon v. Justice, 127 U.S. 700 (1888)". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b Rice p. 111.

- ^ Rice p. 13.

- ^ Rice p. 17.

- ^ a b c Munsey Magazine.p.508. Books.google.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Rice pp. 24, 27.

- ^ Rice p. 28.

- ^ Rice pp. 33–35.

- ^ Rice pp. 62–63.

- ^ Munsey Magazine.p.508-509. Books.google.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "The Evening Bulletin, Maysville Ky, February 19, 1890. p.4". Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Game Show Network airs milestone episodes, including Hatfield-McCoy battle.[1]

- ^ "Family Feud episode clip". YouTube. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Hatfield McCoy Feud Tour App Page".

- ^ "The Hatfield–McCoy reunion". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Hatfields' Family Feud Cemetery". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Hatfield–McCoy Regional Recreation Area". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Hatfield and McCoy Reunion Festival and Marathon." Holidays, Festivals, and Celebrations of the World Dictionary. Detroit: Omnigraphics, Inc., 2010. Credo Reference. Web. September 17, 2012.

- ^ Hatfields, McCoys work together with experts to help pinpoint key battle site in famous feud The Daily Courier (Kelowna) August 7, 2015

- ^ Our Hospitality at IMDb

- ^ The Martins and the Coys at IMDb

- ^ Roseanna McCoy at IMDb

- ^ Comin' Round the Mountain at IMDb

- ^ "Hillbilly Hare" at IMDb

- ^ Comin' Round the Mountain at IMDb

- ^ The Hatfields and the McCoys at IMDb

- ^ Pumpkinhead: Blood Feud at IMDb

- ^ Hatfields & McCoys: Bad Blood at IMDb

- ^ "The Coffin Quilt". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Patrick Salkeld, "The Bitter Feud Between the Hatfields and McCoys of West Virginia"". Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Flintstone Hillbillies" at IMDb

- ^ "A Feud Is A Feud" at IMDb

- ^ "Feud with a Dude" at IMDb

- ^ "7 Things You Didn't Know About the Hatfields and McCoys". History.com. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ Maranzani, Barbara (May 29, 2012). "7 Things You Didn't Know About the Hatfields and McCoys". History.com. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- ^ Imbrogno, Douglas (April 14, 2012). "Hatfield & McCoy feud fuels star treatment". Gazette-Mail. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hatfields & McCoys". History.com. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hatfields & McCoys (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hatfields & McCoys' is a ratings record-setter", Associated Press, June 1, 2012, archived from the original on June 5, 2012

- ^ "Hatfields & McCoys at Internet Movie Database". IMDb. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ "Chicago Tribune article "NBC passes on 'Hatfields,' six other pilots, cancels 'Deception'"". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ Shattuck, Kathryn (August 1, 2013). "What's On Thursday". New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt3328416/

- ^ Majungas

- ^ Hear the Roar-iTunes

- ^ a b Rice (inside rear cover).

- ^ "Family Group Record – Randolph 'Ranel' MCCOY (AFN:1RJ9-QNF)". FamilySearch.org. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

Further reading

- Dotson, Tom (2013). The Hatfield & McCoy Feud after Kevin Costner: Rescuing History. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 354. ISBN 978-1484177853.

- Alther, Lisa (2012). Blood Feud: The Hatfields & the McCoys: The Epic Story of Murder and Vengeance. Lyons Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-7627-7918-5.

- Rice, Otis K (1982). The Hatfields and McCoys. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1459-4.

- Pearce, John Ed (1994). Days of Darkness: The Feuds of Eastern Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1874-3.

- U.S. Supreme Court Mahon v. Justice, 127 U.S. 700 (1888)

- Jones, Virgil Carrington. The Hatfields and the McCoys. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1948. ISBN 0-89176-014-8.

- Waller, Altina L. Feud: Hatfields, McCoys, and Social Change in Appalachia, 1860–1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988. ISBN 0-8078-4216-8.

- King, Dean (2013). The Feud: the Hatfields & McCoys, the true story. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-316-16706-2.

External links

- Listen online – The Story of the Hatfields and McCoys – The American Storyteller Radio Journal

- Hatfield–McCoy Feud West Virginia Division of Culture and History

- Roseanna McCoy at IMDb

- The Hatfields and the McCoys at IMDb (1975)

- Hatfields & McCoys at IMDb (2012)