Haydn's skull

The skull of composer Joseph Haydn was stolen shortly after his death in 1809; the perpetrators were interested in examining it for purposes of phrenology. The thieves were identified eleven years later, but as a result of their clever maneuvering went unpunished. For 145 years, the skull was passed from owner to owner; only in 1954 was it reunified for burial with the rest of Haydn's remains.

Theft

[edit]Haydn died in Vienna, aged 77, on May 31, 1809, after a long illness. As Austria was at war and Vienna occupied by Napoleon's troops,[1] a rather simple funeral was held in Gumpendorf, the parish in Vienna to which Haydn's house on the Windmühle belonged, followed by burial in the Hundsturm cemetery.[2] Following the burial, two men conspired to bribe the gravedigger and thereby sever and steal the dead composer's head. These were Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a former secretary of the Esterházy family (Haydn's employers), and Johann Nepomuk Peter, governor of the provincial prison of Lower Austria.[3] Rosenbaum was well known to Haydn, who during his lifetime had intervened with the Esterházys in an attempt to make possible Rosenbaum's marriage to the soprano Therese Gassmann.[4]

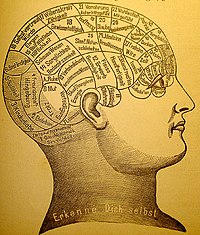

Peter and Rosenbaum's motivation was an interest in phrenology, a now-discredited scientific movement that attempted to associate mental capacities with aspects of cranial anatomy; Peter and Rosenbaum were acquainted with and admired the work of Franz Joseph Gall, a leading phrenologist.[5] Of particular interest to phrenology was the anatomy of individuals held to have exhibited great genius during their lifetime. (Eighteen years later, a similar attempt was made on the body of Ludwig van Beethoven, possibly for similar reasons.)[6]

The head was stolen by the gravedigger (whose name was Jakob Demuth) only on June 4, and due to hot weather the head had decomposed considerably, causing Rosenbaum to throw up as he delivered it in a carriage to the hospital for dissection. According to Landon, "after an examination of an hour the head was macerated and the skull bleached."[7] Peter concluded that "the bump of music" in Haydn's skull was indeed "fully developed".[8] In September, the skull was installed in Peter's collection at his home, where it could be shown to visitors.[7] Peter kept it in a handsome custom-made black wooden box, with a symbolic golden lyre at the top, glass windows, and a white cushion. At some point in the ensuing decade, Peter gave up his skull collection and let Rosenbaum have, among others, the Haydn skull.[7]

Prince Esterházy's intervention

[edit]In 1820, Haydn's old patron Prince Nikolaus Esterházy II was inadvertently reminded by the chance remark of an acquaintance that he had forgotten to carry through his plan of having Haydn's remains transferred from Gumpendorf to the family seat in Eisenstadt.[9]

Upon exhumation, they found a body with a wig above its severed neck. Haydn was in two. Nikolaus was enraged, and quickly deduced that Peter and Rosenbaum were responsible. [10] However, through a series of devious maneuvers (blaming a deceased doctor, two fake skulls; one rejected) Peter and Rosenbaum managed to maintain possession of the skull. Rosenbaum hid the skull in a straw mattress. During the search of Rosenbaum's house, his wife Therese lay on the bed and claimed to be menstruating—with the result that the searchers did not go near the mattress.[11] Eventually Rosenbaum gave Prince Esterházy a different skull.

Subsequent history

[edit]

After Rosenbaum's death in 1829, the skull passed from hand to hand. Rosenbaum had willed the skull to Peter, who gave it to his physician Karl Heller, from whom it went to a Professor Rokitansky, who in 1895 gave it to the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of the Friends of Music).[7] The musicologist Karl Geiringer, who worked at the Society before the advent of Hitler, would on occasion proudly bring out the relic and show it to visitors.[12]

In 1932, Prince Paul Esterházy, Nikolaus's descendant, built a marble tomb for Haydn in the Bergkirche in Eisenstadt. This was a suitable location, since it is where some of the masses Haydn wrote for the Esterházy family were premiered. The Prince's express purpose was to unify the composer's remains.[13] However, there were many further delays, and it was only in 1954 that the skull could be transferred, in a splendid ceremony, from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde to this tomb, thus completing the 145-year-long burial process. When the composer's skull was finally restored to the remainder of his skeleton, the substitute skull was not removed. Thus Haydn's tomb now contains two skulls.[11]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Webster (2002), p. 43

- ^ Geiringer & Geiringer (1982), p. 190

- ^ R (1932)

- ^ The marriage did ultimately take place in 1800, after Rosenbaum had left Esterházy employment. Rice (2009)

- ^ Landon (2009), p. 152

- ^ According to Beethoven's biographer, Anton Schindler, the gravedigger told him that he had turned down a bribe of 1000 florins for delivering the great composer's severed head. Albrecht (1996), p. 215

- ^ a b c d Landon (2009), p. 153

- ^ Geiringer & Geiringer (1982)

- ^ Specifically, to the Esterházy family crypt in the Bergkirche. Landon (2009), p. 153

- ^ The Ross, Greg (7 September 2015). "Futility Closet Podcast Ep 72". Futility Closet.

- ^ a b Hunting Haydn's Head, BBC Radio 4 broadcast by Simon Townley, 30 May 2009

- ^ Geiringer (1947)

- ^ M. M. S. (1948)

Bibliography

[edit]Note: except where specified, all information was taken from the final chapter of Geiringer & Geiringer 1982.

- Albrecht, Theodore (1996). Letters to Beethoven and Other Correspondence: 1824–1828. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1040-X.

- Geiringer, Karl (1947). Haydn: A Creative Life in Music (1st ed.). London: Allen & Unwin.

- Geiringer, Karl; Geiringer, Irene (1982). Haydn: A Creative Life in Music (3rd ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04316-2.

- Hadden, James Cuthbert (1902). Haydn. Master Musicians. London: J.M. Dent & Co.

- Landon, Else Radant (2009). "Haydn's skull". In Jones, David Wyn (ed.). Oxford Composer Companions: Haydn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- "M. M. S." (anonymous author) (April 1948). "Review of Geiringer, Haydn: A Creative Life in Music". Music & Letters. 29 (2): 179–82. JSTOR 730888.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Pohl, Carl Ferdinand; Botstiber, Hugo (1878). Joseph Haydn (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Archived from the original on 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- "R." (anonymous author) (October 1, 1932). "The Skull of Joseph Haydn". The Musical Times. 73 (1076): 942–43. JSTOR 919530.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Rice, John A. (2009). "Rosenbaum, Joseph Carl". In Jones, David Wyn (ed.). Oxford Composer Companions: Haydn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Webster, James (2002). The New Grove Haydn. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Further reading

[edit]- "Haydn's skull is returned: After theft 145 years ago body is complete". Life. Vol. 36, no. 26. June 28, 1954. pp. 51–54.