Homestead strike: Difference between revisions

Frankenpuppy (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 208.67.140.161 to last version by Frankenpuppy (HG) |

|||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

For its part, the AA saw substantial gains after the 1889 strike. Membership doubled, and the local union treasury had a balance of $146,000. The Homestead union grew belligerent, and relationships between workers and managers grew tense.<ref>Brody, p. 54-55.</ref> |

For its part, the AA saw substantial gains after the 1889 strike. Membership doubled, and the local union treasury had a balance of $146,000. The Homestead union grew belligerent, and relationships between workers and managers grew tense.<ref>Brody, p. 54-55.</ref> |

||

==Nature of the 1892 strike== |

==Nature of the 1892 strike fuck off== |

||

The AA strike at the Homestead steel mill in 1892 was different from previous large-scale strikes in American history such as the [[Great railroad strike of 1877]] or the [[Great Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886]]. Earlier strikes had been largely leaderless and disorganized mass uprisings of workers. The Homestead strike was organized and purposeful, a harbinger of the type of strike which would mark the modern age of labor relations in the United States.<ref>Technically, the Homestead job action was a lockout, not a strike. Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 153; Foner, p. 208.</ref> |

The AA strike at the Homestead steel mill in 1892 was different from previous large-scale strikes in American history such as the [[Great railroad strike of 1877]] or the [[Great Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886]]. Earlier strikes had been largely leaderless and disorganized mass uprisings of workers. The Homestead strike was organized and purposeful, a harbinger of the type of strike which would mark the modern age of labor relations in the United States.<ref>Technically, the Homestead job action was a lockout, not a strike. Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 153; Foner, p. 208.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:22, 9 October 2008

The Homestead Strike was a labor lockout and strike which began on June 30, 1892, culminating in a battle between strikers and private security agents on July 6, 1892. It is one of the most serious labor disputes in U.S. history. The dispute occurred in the Pittsburgh-area town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, between the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers (the AA) and the Carnegie Steel Company.

The AA was an American labor union formed in 1876. A craft union, it represented skilled iron and steel workers.

The AA's membership was concentrated in ironworks west of the Allegheny Mountains. The union negotiated national uniform wage scales on an annual basis; helped regularize working hours, workload levels and work speeds; and helped improve working conditions. It also acted as a hiring hall, helping employers find scarce puddlers and rollers.[1]

Early union activity at Homestead

The AA organized the independently-owned Pits Bessemer Steel Works in Homestead in 1881. The AA engaged in a bitter strike at the Homestead works on January 1, 1882 in an effort to prevent management from forcing yellow-dog contracts on all workers. Violence occurred on both sides, and the plant brought in numerous strikebreakers.The strike ended on March 20 in a complete victory for the union.[2]

The AA struck the plant again on July 1, 1889, when negotiations for a new three-year collective bargaining agreement failed. The strikers seized the town and once again made common cause with various immigrant groups. Backed by 2,000 townspeople, the strikers drove off a trainload of strikebreakers on July 10. When the sheriff returned with 125 newly deputized agents two days later, the strikers rallied 5,000 townspeople to their cause. Although victorious, the union agreed to significant wage cuts that left tonnage rates less than half those at the nearby Jones and Laughlin works, where technological improvements had not been made.[3]

Carnegie officials conceded that the AA essentially ran the Homestead plant after the 1889 strike. The union contract contained 58 pages of footnotes defining work-rules at the plant and strictly limited management's ability to maximize output.[4]

For its part, the AA saw substantial gains after the 1889 strike. Membership doubled, and the local union treasury had a balance of $146,000. The Homestead union grew belligerent, and relationships between workers and managers grew tense.[5]

Nature of the 1892 strike fuck off

The AA strike at the Homestead steel mill in 1892 was different from previous large-scale strikes in American history such as the Great railroad strike of 1877 or the Great Southwest Railroad Strike of 1886. Earlier strikes had been largely leaderless and disorganized mass uprisings of workers. The Homestead strike was organized and purposeful, a harbinger of the type of strike which would mark the modern age of labor relations in the United States.[6]

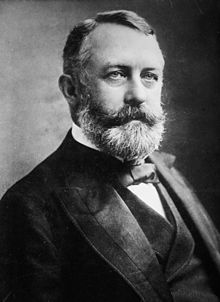

Carnegie and Frick's plans

Andrew Carnegie placed industrialist Henry Clay Frick in charge of his company's operations in 1881.[7] Frick resolved to break the union at Homestead. "The mills have never been able to turn out the product they should, owing to being held back by the Amalgamated men." he complained in a letter to Carnegie.[8]

Carnegie was publicly in favor of labor unions. He condemned the use of strikebreakers and told associates that no steel mill was worth a single drop of blood. But Carnegie agreed with Frick's desire to break the union and "reorganize the whole affair, and . . . exact good reasons for employing every man. Far too many men required by Amalgamated rules."[9] Carnegie ordered the Homestead plant to manufacture large amounts of inventory so the plant could weather a strike. He also drafted a notice (which Frick never released) withdrawing recognition of the union.[10]

With the collective bargaining agreement due to expire on June 30, 1892, Frick and the leaders of the local AA union entered into negotiations in February. With the steel industry doing well and prices higher, the AA asked for a wage increase. Frick immediately countered with a 22 percent wage decrease that would affect nearly half the union's membership and remove a number of positions from the bargaining unit. Carnegie encouraged Frick to use the negotiations to break the union: "...the Firm has decided that the minority must give way to the majority. These works, therefore, will be necessarily non-union after the expiration of the present agreement."[11] Frick then unilaterally announced on April 30, 1892 that he would bargain for 29 more days. If no contract was reached, Carnegie Steel would cease to recognize the union. Carnegie formally approved Frick's tactics on May 4.[12]

Lockout

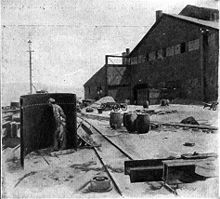

Frick locked workers out of the plate mill and one of the open hearth furnaces on the evening of June 28. When no collective bargaining agreement was reached on June 29, Frick locked the union out of the rest of the plant. A high fence topped with barbed wire, begun in January, was completed and the plant sealed to the workers. Sniper towers with searchlights were constructed near each mill building, and high-pressure water cannons (some capable of spraying boiling-hot liquid) were placed at each entrance. Various aspects of the plant were protected, reinforced or shielded.[13]

At a mass meeting on June 30, local AA leaders reviewed the final negotiating sessions and announced that the company had broken the contract by locking out workers a day before the contract expired. The Knights of Labor, which had organized the mechanics and transportation workers at Homestead, agreed to walk out alongside the skilled workers of the AA. Workers at Carnegie plants in Pittsburgh, Duquesne, Union Mills and Beaver Falls struck in sympathy the same day.[14]

The striking workers were determined to keep the plant closed. They secured a steam-powered river launch and several rowboats to patrol the Monongahela River, which ran alongside the plant. Men also divided themselves into units along military lines. Picket lines were thrown up around the plant and the town, and 24-hour shifts established. Ferries and trains were watched. Strangers were challenged to give explanations for their presence in town; if one was not forthcoming, they were escorted outside the city limits. Telegraph communications with AA locals in other cities were established to keep tabs on the company's attempts to hire replacement workers. Reporters were issued special badges which gave them safe passage through the town, but the badges were withdrawn if it was felt misleading or false information made it into the news. Tavern owners were even asked to prevent excessive drinking.[15]

Frick was also busy. The company placed ads for replacement workers in newspapers as far away as Boston, St. Louis and even Europe.[16]

But unprotected strikebreakers would be driven off. On July 4, Frick formally requested that Sheriff William H. McCleary intervene to allow supervisors access to the plant. Carnegie corporation attorney Philander Knox gave the go-ahead to the sheriff on July 5, and McCleary dispatched 11 deputies to the town to post handbills ordering the strikers to stop interfering with the plant's operation. The strikers tore down the handbills and told the deputies that they would not turn over the plant to nonunion workers. Then they herded the deputies onto a boat and sent them downriver to Pittsburgh.[17]

Battle on July 6

After consultations with Knox, Frick in April 1892 had contracted with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to provide security at the plant. His intent was to open the works with nonunion men on July 6. Knox devised a plan to get the Pinkertons onto the mill property. With the mill ringed by striking workers, the agents would access the plant grounds from the river. Three hundred Pinkerton agents assembled on the Davis Island Dam on the Ohio River about five miles below Pittsburgh at 10:30 p.m. on the night of July 5, 1892. They were given Winchester rifles, placed on two specially-equipped barges and towed upriver.[18]

The strikers were prepared for them. The AA had learned of the Pinkertons as soon as they had left Boston for the embarkation point. The strikers blew the plant whistle at 2:30 a.m., drawing thousands of men, women and children to the plant. The small flotilla of union boats went downriver to meet the barges. Strikers on the steam launch fired a few random shots at the barges, then withdrew—blowing the launch whistle to alert the plant.[19]

Pinkertons attempt to land

The Pinkertons attempted to land under cover of darkness about 4 a.m. A large crowd of families had kept pace with the boats as they were towed by a tug into the town. A few shots were fired at the tug and barges, but no one was injured. The crowd tore down the barbed-wire fence and strikers and their families surged onto the Homestead plant grounds. Some in the crowd threw stones at the barges, but strike leaders shouted for restraint.[20]

The Pinkerton agents attempted to disembark. Conflicting testimony exists as to which side fired the first shot. According to unnamed and unidentified witnesses,[citation needed] Pinkertons shot first. According to witnesses who gave their names and identities, unionists shot first[21].

Frederick Heinde, captain of the Pinkertons, and William Foy, a worker, were both wounded. The Pinkerton agents aboard the barges then fired into the crowd, killing two and wounding 11. The crowd responded in kind, killing two and wounding 12. The firefight continued for about 10 minutes.[22]

The strikers then huddled behind the pig and scrap iron in the mill yard while the Pinkertons cut holes in the side of the barges so they could fire on any who approached. The Pinkerton tug departed with the wounded agents, leaving the barges stranded. The strikers soon set to work building a rampart of steel beams further up the riverbank from which they could fire down on the barges. Hundreds of women continued to crowd on the riverbank between the strikers and the agents, calling on the strikers to 'kill the Pinkertons'.[23]

The strikers continued to sporadically fire on the barges. Union members took potshots at the ships from their rowboats and the steam-powered launch. The burgess of Homestead, John McLuckie, issued a proclamation at 6:00 a.m. asking for townspeople to help defend the peace; more than 5,000 people congregated on the hills overlooking the steelworks. A 20-pounder brass cannon was set up on the shore opposite the steel mill, and an attempt was made to sink the barges. Six miles away in Pittsburgh, thousands of steelworkers gathered in the streets, listening to accounts of the attacks at Homestead; hundreds, many of them armed, began to move toward the town to assist the strikers.[24]

The Pinkertons attempted to disembark again at 8:00 a.m. A striker high up the riverbank fired a shot. The Pinkertons returned fire, and four more strikers were killed (one by shrapnel sent flying when cannon fire hit one of the barges). Many of the Pinkerton agents refused to participate in the firefight any longer; the agents crowded onto the barge farthest from the shore. More experienced agents were barely able to stop the new recruits from abandoning the ships and swimming away. Intermittent gunfire from both sides continued throughout the morning. When the tug attempted to retrieve the barges at 10:50 a.m., gunfire drove it off. More than 300 riflemen positioned themselves on the high ground and kept a steady stream of fire on the barges. Just before noon, a sniper shot dead another Pinkerton agent.[25]

After a few more hours, the strikers attempted to burn the barges. They seized a raft, loaded it with oil-soaked timber and floated it toward the barges. The Pinkertons nearly panicked, and a Pinkerton captain had to threaten to shoot anyone who fled. But the fire burned itself out before it reached the barges. The strikers then loaded a railroad flatcar with drums of oil and set it afire. The flatcar hurtled down the rails toward the mill's wharf where the barges were docked. But the car stopped at the water's edge and burned itself out. Dynamite was thrown at the barges, but it only hit the mark once (causing a little damage to one barge). At 2:00 p.m., the workers poured oil onto the river, hoping the oil slick would burn the barges; attempts to light the slick failed.[26]

Calls for state intervention

The AA worked behind the scenes to avoid further bloodshed and defuse the tense situation. At 9:00 a.m., outgoing AA international president William Weihe rushed to the sheriff's office and asked McCleary to convey a request to Frick to meet. McCleary did so, but Frick refused. He knew that the more chaotic the situation became, the more likely it was that Governor Robert E. Pattison would call out the state militia.[27]

Sheriff McCleary resisted attempts to call for state intervention until 10 a.m. on July 7. In a telegram to Gov. Pattison, he described how his deputies and the Carnegie men had been driven off, and noted that the mob was nearly 5,000-strong. Pattison responded by requiring McCleary to exhaust every effort to restore the peace. McCleary asked again for help at noon, and Pattison responded by asking how many deputies the sheriff had. A third telegram, sent at 3:00 p.m., again elicited a response from the governor exhorting McCleary to raise his own troops.[28]

Pinkerton surrender

At 4:00 p.m., events at the mill quickly began to wind down. More than 5,000 men—most of them armed mill hands from the nearby South Side, Braddock and Duquesne works—arrived at the Homestead plant. Weihe urged the strikers to let the Pinkertons surrender, but he was shouted down. Weihe tried to speak again. But this time, his pleas were drowned out as the strikers bombarded the barges with fireworks left over from the recent Independence Day celebration. Hugh O'Donnell, a heater in the plant and head of the union's strike committee, then spoke to the crowd. He demanded that each Pinkerton be charged with murder, forced to turn over his arms and then be removed from the town. The crowd shouted their approval.[29]

The Pinkertons, too, wished to surrender. At 5:00 p.m., they raised a white flag and two agents asked to speak with the strikers. O'Donnell guaranteed them safe passage out of town. As the Pinkertons crossed the grounds of the mill, the crowd formed a gauntlet through which the agents passed. Men and women threw sand and stones at the Pinkerton agents, spat on them and beat them. Several Pinkertons were clubbed into unconsciousness. Members of the crowd ransacked the barges, then burned them to the waterline.[30]

As the Pinkertons were marched through town to the Opera House (which served as a temporary jail), the townspeople continued to assault the agents. Two agents were beaten as horrified town officials looked on. The press expressed shock at the treatment of the Pinkerton agents, and the torrent of abuse helped turn media sympathies away from the strikers.[31]

The strike committee met with the town council to discuss the handover of the agents to McCleary. But the real talks were taking place between McCleary and Weihe in McCleary's office. At 10:15 p.m., the two sides agreed to a transfer process. A special train arrived at 12:30 a.m. on July 7. McCleary, the international AA's lawyer and several town officials accompanied the Pinkerton agents to Pittsburgh.[32]

But when the Pinkerton agents arrived at their final destination in Pittsburgh, state officials declared that they would not be charged with murder (as per the agreement with the strikers) but rather simply released. The announcement was made with the full concurrence of the AA attorney. A special train whisked the Pinkerton agents out of the city at 10:00 a.m. on July 7.[33]

Arrival of the state militia

On July 7, the strike committee sent a telegram to Gov. Pattison to attempt to persuade him that law and order had been restored in the town. Pattison replied that he had heard differently. Union officials traveled to Harrisburg and met with Pattison on July 9. Their discussions revolved not around law and order, but the safety of the Carnegie plant.[34]

Pattison, however, remained unconvinced by the strikers' arguments. Although Pattison had ordered the Pennsylvania militia to muster on July 6, he had not formally charged it with doing anything. Pattison's refusal to act rested largely on his concern that the union controlled the entire city of Homestead and commanded the allegiance of its citizens. Pattison refused to order the town taken by force, for fear a massacre would occur. But once emotions had died down, Pattison felt the need to act. He had been elected with the backing of a Carnegie-supported political machine, and he could no longer refuse to protect Carnegie interests.[35]

The steelworkers resolved to meet the militia with open arms, hoping to establish good relations with the troops. But the militia managed to keep its arrival in the town a secret almost to the last moment. At 9:00 a.m. on July 12, the Pennsylvania state militia arrived at the small Munhall train station near the Homestead mill (rather than the downtown train station as expected). More than 4,000 soldiers surrounded the plant. Within 20 minutes they had displaced the picketers; by 10:00 a.m., company officials were back in their offices. Another 2,000 troops camped on the high ground overlooking the city.[36]

The company quickly brought in strikebreakers and restarted production under the protection of the militia. Despite the presence of AFL pickets in front of several recruitment offices across the nation, Frick easily found employees to work the mill. The company quickly built bunk houses, dining halls and kitchens on the mill grounds to accommodate the strikebreakers. New employees, many of them black, arrived on July 13, and the mill furnaces relit on July 15. When a few workers attempted to storm into the plant to stop the relighting of the furnaces, militiamen fought them off and wounded six with bayonets.[37]

Desperate to find a way to continue the strike, the AA appealed to Whitelaw Reid, the Republican candidate for vice president, on July 16. The AA offered to make no demands or set any preconditions; the union merely asked that Carnegie Steel reopen the negotiations. Reid wrote to Frick, warning him that the strike was hurting the Republican ticket and pleading with him to reopen talks. Frick refused.[38]

Company legal retaliation

Frick, too, needed a way out of the strike. The company could not operate for long with strikebreakers living on the mill grounds, and permanent replacements had to be found.

Legal retaliation against the strikers proved to be the most promising avenue for the company. On July 18, 16 of the strike leaders were charged with conspiracy, riot and murder. Company lawyer Knox drew up the charges on behalf of state authorities. Each man was jailed for one night and forced to post a $10,000 bond. The union retaliated by charging company executives with murder as well. The company men, too, had to post a $10,000 bond, but they were not forced to spend any time in jail. The same day, the town was placed under martial law, further disheartening many of the strikers.[39]

National attention became riveted on Homestead when, on July 23, Alexander Berkman, an anarchist, gained entrance to Frick's office, shot him twice in the neck and then stabbed him twice with a knife. Berkman was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 22 years in prison.[40]

The Berkman incident prompted the final collapse of the strike. Hugh O'Donnell, without consulting his colleagues on the strike committee, offered what amounted to unconditional surrender to the company. He then leaked his proposal to the press. When confronted by angry co-workers and surprised reporters, he feigned ignorance—but then told the press he agreed with the plan. O'Donnell was removed as chair of the strike committee. The perceived betrayal by one of their own threw the committee into despair. On August 12, the company announced that 1,700 men were working at the mill and production had resumed at full capacity. Dismayed, the strike committee largely ceased to function.[41]

Additional legal ammunition against the strikers was levied in the fall. Knox had engaged in ex parte communication with Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chief Justice Edward Paxson. Knox submitted charges to Paxson which accused all 33 members of the strike committee with treason under the state's Crimes Act of 1860. In Pittsburgh for the court's fall term, Paxson (after conferring with Knox once more) issued the treason charges himself on August 30. A $500,000 bond was required. Most of the men could not raise the money, and went to jail while awaiting trial; a few simply went into hiding. Legal scholars were outraged by clear abuse of the law, and deeply concerned by Paxson's apparently biased behavior. State prosecutors, worried by the flimsy nature of the charges, declined to prosecute.[42]

The strike's conclusion

Support for the strikers evaporated. The AFL refused to call for a boycott of Carnegie products in September 1892. Wholesale crossing of the picket line occurred, first among Eastern European immigrants and then among all workers. The strike had collapsed so much that the state militia pulled out on October 13, ending the 95-day occupation. The AA was nearly bankrupted by the job action. Nearly 1,600 men were receiving a total of $10,000 a week in relief from union coffers. With only 192 out of more than 3,800 strikers in attendance, the Homestead chapter of the AA voted, 101 to 91, to return to work on November 20, 1892.[43]

In the end, only four workers were ever tried on the actual charges filed on July 18. Three AA members were found innocent of all charges. Hugh Dempsey, the leader of the local Knights of Labor District Assembly, was found guilty of conspiring to poison nonunion workers at the plant—despite the state's star witness recanting his testimony on the stand. Dempsey served a seven-year prison term. In February 1893, Knox and the union agreed to drop the charges filed against one another, and no further prosecutions emerged from the events at Homestead.[44]

The striking AA affiliate in Beaver Falls gave in the same day as the Homestead lodge. The AA affiliate at Union Mills held out until August 14, 1893. But by then the union had only 53 members. The union had been broken; the company had been operating the plant at full capacity for almost a year, since September 1892.[45]

Aftermath

The Homestead strike broke the AA as a force in the American labor movement. Many employers refused to sign contracts with their AA unions while the strike lasted. A deepening in 1889 of the Long Depression led most steel companies to seek wage decreases similar to those imposed at Homestead.[46]

An organizing drive at the Homestead plant in 1896 was crushed by Frick. In May 1899, 300 Homestead workers actually formed an AA lodge, but Frick ordered the Homestead works shut down and the unionization effort collapsed. Carnegie Steel remained nonunion for the next 40 years.[47]

De-unionization efforts throughout the Midwest began against the AA in 1897 when Jones and Laughlin Steel refused to sign a contract. By 1900, not a single steel plant in Pennsylvania remained union. The AA presence in Ohio and Illinois continued for a few more years, but the union continued to collapse. Many lodges disbanded, their members disillusioned. Others were easily broken in short battles. Carnegie Steel's Mingo Junction, Ohio plant was the last major unionized steel mill in the country. But it, too, successfully withdrew recognition without a fight in 1903.[48]

AA membership sagged to 10,000 in 1894 from its high of over 24,000 in 1891. A year later, it was down to 8,000. A 1901 strike against U.S. Steel collapsed. By 1909, membership in the AA had sunk to 6,300. A nationwide steel strike of 1919 also was unsuccessful.[49]

The AA maintained a rump membership in the steel industry until its takeover by the Steel Workers Organizing Committee in 1936. The two organizations officially disbanded and formed the United Steelworkers May 22, 1942.

In 1999 the Bost Building in downtown Homestead, AA headquarters throughout the strike, was designated a National Historic Landmark. It is used as a museum devoted to not only the strike but the steel industry in the Pittsburgh area.

Notes

- ^ Brody, p. 50.

- ^ Krause, p. 174-192; Body, p. 50-51.

- ^ Brody, p. 52; Krause, p. 42, 174, 246-249.

- ^ Brody, p. 53.

- ^ Brody, p. 54-55.

- ^ Technically, the Homestead job action was a lockout, not a strike. Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 153; Foner, p. 208.

- ^ Frick had ruthlessly broken unions in the coke-producing regions of Pennsylvania and Ohio, and crushed the seamen's unions on the Great Lakes. Foner, p. 207.

- ^ Quoted in George Harvey, Henry Clay Frick: The Man (New York: Beard Books, 1928; reprinted 2002), p. 177. ISBN 1-58798-127-0

- ^ Quoted in James H. Bridge, The Inside History of the Carnegie Steel Company (New York: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1903; rev. ed. 1992), p. 206. ISBN 0-405-04112-8

- ^ Carnegie, a pacifist, purposefully avoided the moral dilemmas raised by the Homestead strike by beginning a European vacation before the strike began. When questioned in Scotland about Frick's actions, Carnegie washed his hands of any responsibility and declared that Frick was in charge. Brody argues that Carnegie felt Frick was doing the right thing by bringing in strikebreakers and busting the union, but that Frick was doing a poor job of it. See Brody, p. 59 fn. 18; see also Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 155-56.

- ^ Letter from Carnegie to Frick dated April 4, 1892, quoted in Foner, p. 207.

- ^ The AA represented about 800 of the 3,800 workers at the plant. Foner, p. 206-207; Rayback, p. 195-96; Brody, p. 53; Krause, p. 302-03. Krause, p. 284-310, contains the best discussion of the bargaining timeline and exchange of proposals.

- ^ Foner, footnote p. 207; Foner, p. 208; Krause, p. 302, 310.

- ^ Foner, footnote, p. 207, and p. 208, 210-11.

- ^ Foner, p. 208-09; Krause, p. 311; Brody, p. 59; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 154.

- ^ Foner, p. 209.

- ^ Krause, p. 26. Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 154, claim these were plant guards specially deputized, but Krause is more authoritative in this regard.

- ^ Foner, p. 209; Krause, p. 15, 271. The barges, bought specifically for the Homestead lockout, contained sleeping quarters and kitchens and were intended to house the agents for the duration of the strike.

- ^ Foner, p. 209; Krause, p. 16. Krause indicates that at least a thousand people turned out.

- ^ Krause, p. 16-18. Brody cites Andrew Carnegie, who claimed that Frick had not extended the barbed-wire fence to the riverbank, thus allowing the strikers access to the plant grounds. Brody, p. 59. But Foner says that the strikers tore down the fence near the water's edge. Foner, p. 209. Supporting Foner, see Krause, p. 17.

- ^ New York Times, 1892, July 7, page 2, John T. McCurry

tells us.

I was down at the foot of Beaver Avenue, Allegheny, yesterday, when Captain Rogers employed me to go up the river on his boat - the Little Bill

Our boat had in tow one barge of Pinkerton men and the Tide had the other. While going up, the Tide was disabled, and we took our barge up in front of Homestead, and then went back for the Tide's.

We made a landing at the Homestead mills about five o'clock this morning. The shore was crowded with the locked out men and their sympathizers.

The armed Pinkerton men commenced to climb up the banks. Then the workmen opened fire on the detectives. The men shot first, and not until three of the Pinkerton men had fallen did they respond to the fire. I am willing to take an oath that the workmen fired first, and that the Pinkerton men did not shoot until some of their number had been wounded.

The workmen were so strong in numbers that it was useless for the three fifty or four hundred Pinkerton men to oppose them further, so they retreated to the barges, carrying their dead and wounded.

One Pinkerton man was shot through the head and instantly killed, and five were wounded.

We backed out into the river, anchored the barges, and then took the dead and wounded men up to Port Perry, whence they were sent on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to Pittsburgh. We then went down to Homestead again.

We were going along peaceably and expecting no trouble. When we reached the mills the strikers opened fire on the Little Bill from both sides. It was then I was hit.

The bullets broke the glass and splintered the woodwork. Captain Alexander McMichaels was at the wheel. The bullets crashed through the glass pilothouse, and to save his life, he had to rush below. Captain Rogers was on board, and he displayed great bravery.

When the firing commenced, we all laid down on the floor to escape the bullets, but I was not quick enough, and was wounded. There was cessation in the firing, and the pilot secured control of the boat before it ran into the bank, which it came near doing.

There was no one on board at the time we were fired upon, but the crew, Captain Rogers, and one Pinkerton man, J.H. Robinson of Chicago.

When we approached Homestead from Port Perry we could see the attempts to set fire to the barges.

The strikers had a carload of what appeared to be oil, and were pouring it on the river and igniting it. The barges at this time were out in the middle of the river.

- ^ Krause is the most accurate source on the number of dead, including the names of the killed and wounded. Krause, p. 19-20.

- ^ Krause, p. 20-21.

- ^ Krause, p. 21-22; Brody, p. 59.

- ^ Krause, p. 22-25, 30; Brody, p. 59.

- ^ Krause, p. 24; Foner, p. 210.

- ^ Krause, p. 25-26. Frick had sought several times to have the Pinkerton agents deputized. He guessed correctly that the strikers would attack the Pinkertons, and attacking duly deputized county law enforcement officers would provide grounds for claiming insurrection. McCleary, sympathizing with the workers, refused Frick's demands. See Krause, p. 26-28.

- ^ Krause, p. 29-30.

- ^ Krause, p. 32-34.

- ^ Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 154; Krause, p. 34-36. Krause documents two more incidents which occurred during the surrender. A striker seized a Pinkerton agent's rifle and attempted to break it in two. He succeeded in shooting himself in the stomach, and died. Later, as the agents passed through the gauntlet, a woman poked out an agent's eye with her umbrella.

- ^ Krause, p. 36-38. Krause points out that much of the press' lurid reporting played heavily on misogynistic ideals of women as respectable and docile. The press also often described the women of the town as 'Hungarians,' playing on nativist hatreds.

- ^ Krause, p. 38-39.

- ^ Krause, p. 40-41.

- ^ Krause, p. 332-34.

- ^ Krause, p. 32, 333-34; Foner, p. 212; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 154-55.

- ^ Krause, p. 337-38.

- ^ Foner, p. 211, 212; Krause, p. 337-39; Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 154-55. But all was not well inside the plant. A race war between nonunion black and white workers in the Homestead plant broke out on July 22, 1892. See Krause, p. 346.

- ^ Brody, p. 55-56; Krause, 343-44.

- ^ Foner, p. 213-14; Krause, p. 345.

- ^ Dubofsky and Dulles, p. 155; Krause, p. 354-55; Rayback, p. 196. W.L. Iams, a young militiaman stationed in Homestead, cheered the attempt on Frick's life. The commander of the state militia had Iams hung by his thumbs in the yard of the steel mill. Iams lost consciousness from the intense pain after only 30 minutes. Iams was dishonorably discharged a few days later, and forcibly ejected from camp. See Krause, p. 355.

- ^ Krause, p. 355-57.

- ^ Krause, p. 348-349; Foner, p. 214-215. The Crimes Act of 1860 had been passed at the start of the U.S. Civil War to prevent Pennsylvanians from giving aid and comfort Confederates.

- ^ Krause, p. 356-57; Foner, p. 215-17.

- ^ Krause, p. 348.

- ^ Foner, p. 217.

- ^ Brody, p. 57.

- ^ Brody, p. 56-57.

- ^ Brody, p. 57-58.

- ^ Foner, p. 218.

References

- Brody, David. Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1969. ISBN 0-252-06713-4

- Dubofsky, Melvyn and Dulles, Foster Rhea. Labor in America: A History. 6th ed. Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, Inc., 1999. ISBN 0-88295-979-4

- Foner, Philip. History of the Labor Movement in the United States. Vol. 2: From the Founding of the A.F. of L. to the Emergence of American Imperialism. New York: International Publishers, 1955. ISBN 0-7178-0092-X

- Krause, Paul. The Battle for Homestead, 1890-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8229-5466-4

- Rayback, Joseph G. A History of American Labor. Rev. and exp. ed. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1966. ISBN 0-02-925850-2

- Zieger, Robert H. The CIO, 1935-1955. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8078-2182-9