Infant swimming

Infant swimming is the phenomenon of human babies and toddlers controlling their breath and moving themselves through water. Infants will naturally close their lungs underwater and are able to survive immersion in water for short periods of time. Infants can also be given swimming lessons; this is primarily done to reduce the risk of drowning.

Infant swimming or diving reflex

Human babies demonstrate an innate swimming or diving reflex from birth until the age of approximately six months.[1] Other mammals also demonstrate this phenomenon (see mammalian diving reflex). Babies immersed in water will spontaneously hold their breath (apnea), slow their heart rate (reflex bradycardia), and reduce blood circulation to the extremities such as fingers and toes (peripheral vasoconstriction).[1] During the diving reflex, the infant's heart rate decreases by an average of 20%.[1] The top of the infant's lungs is spontaneously sealed off, and water entering the upper respiratory tract is diverted down the esophagus into the stomach.[2] The diving response has been shown to have an oxygen-conserving effect, both during movement and at rest. Oxygen is saved for the heart and the lungs, slowing the onset of serious hypoxic damage. The diving response can therefore be regarded as an important defence mechanism for the body.[3]

Drowning risk

Drowning is a leading cause of unintentional injury and death worldwide, and the highest rates are among children. Overall, drowning is the leading cause of injury death among children aged 1–4 years in the United States, and is the second highest cause of death altogether in that age range, after congenital defects.[4][5]

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study in 2012 of United States data from 2005–2009 indicated that each year an average of 513 children aged 0–4 years were victims of fatal drowning and a further 3,057 of that age range were treated in U.S. hospital emergency departments for non-fatal drowning. Of all the age groups, children aged 0–4 years had the highest death rate and also non-fatal injury rate. In 2009, among children 1 to 4 years old who died from an unintentional injury, more than 30% died from drowning. These children most commonly drowned in swimming pools, often at their own homes.[4][5]

Swimming lessons for infants

Traditionally, swimming lessons started at age four years or later, as children under four were not considered developmentally ready.[6] However, swimming lessons for infants have become more common. The Australian Swimming Coaches and Teachers Association recommends that infants can start a formal program of swimming lessons at four months of age and many accredited swimming schools offer classes for very young children, especially towards the beginning of the swimming season in October.[7] In the US, the YMCA[8] and American Red Cross offer swim classes.[9] A baby has to be able to hold his or her head up (usually at 3 to 4 months), to be ready for swimming lessons.[10]

Children can be taught, through a series of "Prompts and Procedures," to float on their backs to breathe, and then to flip over and swim toward a wall or other safe area. Children are essentially taught to swim, flip over and float, then flip over and swim again. Thus, the method is called "swim, float, swim."[11][12] Infant swimming lessons, sometimes called infant swim recovery, teach infants and toddlers how to recover from an accidental fall into a body of water. Unlike traditional parent/toddler swimming lessons sessions, which teach infants to put their faces in the water and blow bubbles,[13][14] infant swimming lessons instill in the child the skills to roll onto his or her back to float, rest, and breathe, and to maintain this position until help arrives.[15]

Pros and cons of infant swimming lessons

In a 2009 study, participation in formal swimming lessons was associated with an 88% reduction in the risk of drowning in 1- to 4-year-old children, although the authors of the study found the conclusion imprecise.[16][17] Another study showed that infant swimming lessons may improve motor skills, but the number of study subjects was too low to be conclusive.[18]

There may be a link between infant swimming and rhinovirus-induced wheezing illnesses.[19]

Others have indicated concerns that the lessons might be traumatic, that the parents will have a false sense of security and not supervise young children adequately around pools, or that the infant could experience hypothermia, suffer from water intoxication after swallowing water, or develop gastrointestinal or skin infections.[20][21]

Professional positions

The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2014) |

The USA Centers for Disease Prevention and Control recommends swimming lessons for children from 1-4, along with other precautionary measures to prevent drowning.[4][5][22]

In 2010, the American Academy of Pediatrics reversed its previous position in which it had disapproved of lessons before age 4[6] indicating that the evidence no longer supported an advisory against early swimming lessons. However, the AAP stated that it found the evidence at that time insufficient to support a recommendation that all 1- to 4-year-old children receive swimming lessons. The AAP further stated that in spite of the popularity of swimming lessons for infants under 12 months of age and anecdotal evidence of infants having saved themselves, no scientific study had clearly demonstrated the safety and efficacy of training programs for infants that young. The AAP indicated its position that the possible benefit of early swimming instruction must be weighed against the potential risks (e.g., hypothermia, hyponatremia, infectious illness, and lung damage from pool chemicals).[23]

In popular culture

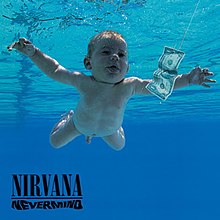

A swimming infant is featured in the Nirvana video of "Come as You Are"[24] and on the cover of its album Nevermind.[25]

In June, 2014, The New York Times featured an article entitled "Little Nemos: Before Learning to Walk You Must Learn to Swim",[26] featuring photographs of underwater babies by Seth Casteel, a photographer with a book pending on that subject, following up on his earlier book on underwater dogs.[27]

References

- ^ a b c Goksor, E.; Rosengren, L.; Wennergren, G. (2002). "Bradycardic response during submersion in infant swimming". Acta Paediatr. 91 (3): 307–312. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Winston, Robert (1998). "The Human Body". BBC. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Alboni, Paolo; Alboni, Marco; Gianfranchi, Lorella (Feb 2011). "Diving bradycardia: a mechanism of defence against hypoxic damage". Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 12 (6): 422–427. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Laosee, Orapin C.; Gilchrist, Julie; Rudd, Rose (May 18, 2012). "Drowning - United States, 2005-2009". Center for Disease Control: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 61 (19): 344–347. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b c "Unintentional Drowning: Get the Facts". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ a b American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. (2000). "Swimming Programs for Infants and Toddlers". Pediatrics. 105 ((4 pt 1)): 868–870. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Swim Australia FAQs". Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ "Parent/Child Swim Lessons (Ages 6-36 months)". New York's YMCA. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Swimming Classes and Water Safety". American Red Cross. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Pratt, Sarah. "Infant Swimming Classes". Parenting. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Chief Judge Babcock (April 16, 2001). "Findings of Fact: Harvey Barnett, Inc. v. Shidler". Court LIstener. 143 F. Supp. 2d: 1247. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit (Aug 15, 2006). "Harvey Barnett, Inc. v. Shidler". Court Listener. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Baby Swim Lessons". Aqua Tots Swim Schools. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Blowing Bubbles - Not Necessary When Learning to Swim". Murray Callan Swim Schools. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "What Your Child Will Learn in ISR Lessons". ISR Infant Swimming Resource Self-Rescue Survival. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Brenner, RA; Taneja, GS; Haynie, DL; Trumble, AC; Qian, C; Klinger, RM; Klebanoff, MA (Mar 2009). "Association between swimming lessons and drowning in childhood: a case-control study". Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 163 (3): 203–10. PMID 19255386.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Moreno, MA; Furtner, F; Rivara, FP (Mar 2009). "Water safety and swimming lessons for children". Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 163 (3): 288. PMID 19255402.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Dias, JA; Manoel Ede, J; Dias, RB; Okazaki, VH (Dec 2013). "Pilot study on infant swimming classes and early motor development". Perceptual and motor skills. 117 (3): 950–5. PMID 24665810.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Schuez-Havupalo, L; Karppinen, S; Toivonen, L; Kaljonen, A; Jartti, T; Waris, M; Peltola, V (Jul 7, 2014). "Association between infant swimming and rhinovirus-induced wheezing". Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). PMID 25041066. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Weeks, Carly (July 13, 2009). "Water Safety: Can a six-month-old save himself from drowning?". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "US babies learn 'self-rescue' from drowning". France-Presse. July 23, 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ "Drowning Happens Quickly– Learn How to Reduce Your Risk". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison, Prevention (Jul 2010). "Prevention of drowning". Pediatrics. 126 (1): 178–85. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1264. PMID 20498166. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nirvana. "Come As You Are". YouTube Vevo. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Nirvana Nevermind". All Music. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Bosman, Julie (June 13, 2014). "Little Nemos: Before Learning to Walk, You Must Learn to Swim". New York Times. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ^ Cliffe, Samantha (Aug 11, 2012). "Underwater dogs: Photography by Seth Casteel". Digital Camera World. Retrieved 18 August 2014.