Portuguese Inquisition

General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal Conselho Geral do Santo Ofício da Inquisição Portuguese Inquisition | |

|---|---|

Seal of the Inquisition | |

| Type | |

| Type | Council under the election of the Portuguese monarchy |

| History | |

| Established | 23 May 1536 |

| Disbanded | 31 March 1821 |

| Seats | Consisted of a Grand Inquisitor, who headed the General Council of the Holy Office |

| Elections | |

| Grand Inquisitor chosen by the Crown and named by the Pope | |

| Meeting place | |

| Portuguese Empire Headquarters: Estaus Palace, Lisbon | |

| Footnotes | |

| See also: Medieval Inquisition Spanish Inquisition Goa Inquisition | |

The Portuguese Inquisition (Portuguese: Inquisição Portuguesa), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King John III. Although King Manuel I had asked for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515 to fulfill the commitment of his marriage with Maria of Aragon, it was only after his death that Pope Paul III acquiesced. In the period after the Medieval Inquisition, it was one of three different manifestations of the wider Christian Inquisition, along with the Spanish Inquisition and Roman Inquisition. The Goa Inquisition was an extension of the Portuguese Inquisition in colonial-era Portuguese India. The Portuguese Inquisition was terminated in 1821.

History

[edit]Background

[edit]In 1478, Pope Sixtus IV issued the papal bull Exigit sincerae devotionis affectus that allowed the installation of the Inquisition in Castile, which created a strong wave of immigration of Jews and heretics to Portugal.[1][2]

It was after these events that the situation of the Jews and Moors in Portugal worsened. Before that, there was not violence against Jews as such. The Portuguese Jews had lived in self-governing communities, called judiarias. The free practice of Judaism and Islam was recognized and guaranteed by law.[3]

On December 5, 1496, as a result of the clause present in his marriage contract with Princess Isabel of Spain, King Manuel I signed an order that forced all Jews to choose between leaving Portugal or converting. However, the number of voluntary conversions was much lower than expected and the king decided to close all ports in Portugal (except Lisbon) to prevent these Jews from escaping.[4]

In April 1497, an order was issued for the forcible removal on Easter Sunday of all Jewish sons and daughters under the age of 14 from those Jews who had chosen to leave Portugal rather than convert. Many of these children were then distributed throughout the country's cities and towns to be educated according to the Christian faith at the king's expense,[5] and it is not known how many managed to return to their biological families.[6] In October 1497, the Jews who did not flee ended up being forcibly baptized,[7] thus giving rise to the so-called New Christians.

Nevertheless, historian A.J. Saraiva tells us that the community of former Jews was on its way to integration when on April 9, 1506 at Lisbon, a mob killed two thousands of New Christians, accused of being the cause of drought and plague that devastated the country.[8] After the three days massacre, the king punished those responsible and renewed the rights that the Jews had before 1497, giving the New Christians the privilege of not being questioned for their religious practices, and authorizing them to leave Portugal freely.[8] But, on August 1515, king Manuel I wrote to his ambassador in Rome, instructing him to ask the Pope for a Castilian-model inquisition decree.[9]

In December 1531, Pope Clement VII granted permission for the Inquisition, but under conditions that the king did not want and did not accept; and in April 1535 the same pope went back on his word, suspended the Inquisition, ordered the general pardon of those guilty of Judaism, the release of prisoners and convicts, and the restitution of confiscated property. The basis for Clement VII's decisions was a report that recalled "the true doctrine on the conversion of the Infidels": persuasion and gentleness, following Christ's example. The report reproduced some information about the workings of the inquisitorial courts, saying the abuses of the inquisitors were such, that it was easy to understand that they were "ministers of Satan and not of Christ", acting like "thieves and mercenaries".[10]

The death of Pope Clement VII prevented the application of the bull of pardon. His successor, Paul III, after several hesitations, put it into effect, and meanwhile king John III of Portugal continued to insist and negotiate, including using the intercession of Charles V, his brother-in-law, to re-establish the Inquisition.[10]

Establishment

[edit]After many years of negotiations between the kings and the popes, the Portuguese Inquisition was established on May 23, 1536, by order of Pope Paul III bull Cum ad nihil magis, and imposed the censorship of printed publications, starting with the prohibition of the Bible in languages other than Latin.[11]

The major target of the Portuguese Inquisition were those who had converted from Judaism to Catholicism, the Conversos (also known as New Christians or Marranos), who were suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. Many of these were originally Spanish Jews who had left Spain for Portugal, when Spain forced Jews to convert to Christianity or leave. The number of these victims ( between 1540 and 1765) is estimated as around 40,000.[12] To a lesser extent people of other ethnicities and faiths, such as African practitioners of diasporic African religions and Vodun smuggled through the Atlantic slave trade from the colonies and territories of the Portuguese Empire, were put on trial and imprisoned with the accusations of heresy and witchcraft by the Portuguese Inquisition.[13] Brazil's Romani community of around 800,000 descended from Sinti and Roma were deported from the Portuguese Empire during the Inquisition.[14]

As in Spain, the Inquisition was subject to the authority of the King, although the Portuguese Inquisition in practice exercised a considerable degree of institutional independence from both the Crown and the papacy compared to its Spanish counterpart.[15] It was headed by a Grand Inquisitor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the king, always from within the royal family. The Grand Inquisitor would later nominate other inquisitors. In Portugal, the first Grand Inquisitor was D. Diogo da Silva, personal confessor of King John III and Bishop of Ceuta. He was followed by Cardinal Henry, brother of John III, who would later become king. There were Courts of the Inquisition in Lisbon, Coimbra, and Évora, and for a short time (1541 until c. 1547) also in Porto, Tomar, and Lamego.

It held its first auto de fé in Portugal in 1540. Like the Spanish Inquisition, it concentrated its efforts on rooting out those who had converted from other faiths (overwhelmingly Judaism) but allegedly did not adhere to the strictures of Catholic orthodoxy.

The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to Portugal's colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa in India, where it continued investigating and trying cases based on supposed breaches of orthodox Catholicism until 1821.

Under John III, the activity of the courts was extended to the censure of books, as well as undertaking cases of divination, witchcraft, and bigamy. Originally aimed at religious matters, the Inquisition had an influence on almost every aspect of Portuguese life – political, cultural, and social.

Many New Christians from Portugal migrated to Goa in the 1500s as a result of the inquisition in Portugal. They were Crypto-Jews and Crypto-Muslims, falsely-converted Jews and Muslims who were secretly practising their old religions. Both were considered a security threat to the Portuguese, because Jews had an established reputation in Iberia for joining forces with Muslims to overthrow Christian rulers.[16] The Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier requested that the Goa Inquisition be set up in a letter dated 16 May 1546 to King John III of Portugal, in order to deal with false converts to Catholicism. The Inquisition began in Goa in 1560.[17] Of the 1,582 persons convicted between 1560 and 1623, 45.2% were convicted for offenses related to Judaism and Islam.[18]

The Goa Inquisition also turned its attention to allegedly falsely-converted and non-convert Hindus. It prosecuted non-convert Hindus who broke prohibitions against the public observance of Hindu rites, and those non-convert Hindus who interfered with sincere converts to Catholicism.[19] A compilation of the auto de fé statistics of the Goa Inquisition from its beginning 1560 till its end in 1821 reveal that a total of 57 persons were burnt in the flesh and 64 in effigy (i.e. a statue resembling the person). All the burnt were convicted as relapsed heretics or for sodomy.[20]

Among the main targets of the Inquisition, were also the Portuguese Christian traditions and movements that were not perceived as orthodox. The millenarian and national Feast of the Cult of the Empire of the Holy Spirit, dating from the mid 13th century, spread throughout all mainland Portugal from then into the 14th century. In the following centuries it spread throughout Portugal's Atlantic islands and empire, where it was the main target of prohibition and surveillance by the Inquisition after the 1540s, since it had almost disappeared from continental Portugal and India. This spiritual tradition, practiced exclusively by non-religious officials and popular Brotherhoods in the Middle Ages and following centuries, was gradually restored only after the second half of the 20th century in some municipalities of mainland Portugal. By then, except for a few faithful and accurate local traditions, it had undergone major deletions and changes (in what remained or was restored) of the ancient rituals.[21][22][23][24]

According to the traditional Feast of the Empire of the Holy Spirit, celebrated at the feast of Pentecost, a future, third age would be governed by the Empire of Holy Spirit and would represent a monastic or fraternal governance, in which the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the intermediaries, and the organized Churches would be unnecessary, and infidels would unite with Christians by free will. Until the 16th century, this was the main annual festivity in most of the major Portuguese cities, with multiple celebrations in Lisbon (with 8), Porto (4), and Coimbra (3). The Church and the Inquisition would not tolerate a spiritual tradition entirely popular and without the mediation of the clergy at the time, and most importantly, celebrating a future Age which would bring an end to the Church.[citation needed]

The cult of the Holy Spirit survived in the Azores Islands among the local population and under the traditional protection of the Order of Christ. Here the arm of the Inquisition did not effectively extend its power, despite reports from local ecclesiastical authorities. Beyond the Azores, the cult survived in many parts of Brazil (where it was established in the 16th through 18th centuries) and is celebrated today in all Brazilian states except two, as well as in pockets of Portuguese settlers in North America (Canada and USA), mainly among those of Azorean descent.[25][26] Afro-Brazilian religious mystic and formerly enslaved prostitute, Rosa Egipcíaca, was imprisoned in both Rio de Janeiro and Lisbon by the Inquisition. She died working in the kitchen of the Lisbon inquisition.[27] Egipcíaca was the author of the first book to be written by a black woman in Brazil - entitled Sagrada Teologia do Amor Divino das Almas Peregrinas it detailed her religious visions and prophecies.[28]

The movements and concepts of Sebastianism and of the Fifth Empire were sometimes also targets of the Inquisition (the most intense persecution of Sebastianists being during the Philippine Dynasty, though it lasted beyond then), both considered unorthodox and even heretical. But targeting was intermittent and selective since some important familiares (associated people) of the Holy Office (Inquisition) were Sebastianists.[citation needed]

The financial problems of King Sebastian in 1577 led him, in exchange for a large sum of money, to allow the free departure of New Christians, and to ban the confiscation of property by the Inquisition for 10 years.[citation needed]

King John IV, in 1649, banned the confiscation of property by the Inquisition, and it is said he was later excommunicated by Rome. It seems that the excommunication was not officially proclaimed because in the meantime the king died.[29] This law was only fully withdrawn around 1656, with the death of the king.[citation needed]

From 1674 to 1681 the Inquisition was suspended in Portugal: autos de fé were suspended and inquisitors were instructed not to inflict sentences of relaxation (hand over to secular justice for execution), confiscation, or perpetual galleys. This was an action of father António Vieira in Rome to put an end to the Inquisition in Portugal and its Empire. Vieira had earned the name of the Apostle of Brazil. At the request of the pope he drew up a report of two hundred pages on the Inquisition in Portugal, with the result that after a judicial inquiry Pope Innocent XI himself suspended it for five years (1676–81).[citation needed]

António Vieira had long regarded the New Christians with compassion and had urged King John IV, with whom he had much influence and support, not only to abolish confiscation but to remove the distinctions between them and the Old Christians. He had made enemies and the Inquisition readily undertook his punishment. His writings in favor of the oppressed were condemned as "rash, scandalous, erroneous, savoring of heresy, and well adapted to pervert the ignorant." After three years of incarceration, he was penanced in the audience-chamber of Coimbra on 23 December 1667. His sympathy for the victims of the Holy Office was sharpened by his experience of its "unwholesome prisons", where he wrote that "five unfortunates were not uncommonly placed in a cell nine feet by eleven, where the only light came from a narrow opening near the ceiling, where the vessels were changed only once a week, and all spiritual consolation was denied." [citation needed]Then, in the safety of Rome, he raised his voice for the relief of the oppressed, in several writings in which he characterized the "Holy Office of Portugal as a tribunal which served only to deprive men of their fortunes, their honor, and their lives, while unable to discriminate between guilt and innocence; it was known to be holy only in name, while its works were cruelty and injustice, unworthy of rational beings, although it was always proclaiming its superior piety."[30]

In 1773 and 1774 Pombaline Reforms ended the Limpeza de Sangue (purity of blood) statutes and their discrimination against New Christians, the Jews and all their descendants who had converted to Christianity in order to escape the Portuguese Inquisition.[citation needed]

Although officially abolished much later, the Portuguese Inquisition lost some of its strength during the second half of the 18th century under the influence of Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, the Marquis of Pombal (1699-1782), who claimed to be clearly opposed to inquisitorial methods, classing them as acts "against humanity and Christian principles".[31] This, despite the fact that he himself (he was a familiar) used the Inquisition for his own ends, such as when he thought it necessary to eliminate Father Gabriel Malagrida, a jesuit, denouncing him to the Inquisition,[32][33] and used clear inhumanity against the Távoras. [33] Paulo de Carvalho e Mendonça, the Marquis of Pombal's brother, headed the Inquisition from 1760 until 1770. [34] The Marquis aim was to transform it a royal court, and not an ecclesiastical one as it had been until then. The heretics continued to be persecuted, as so the "high spirits".[31]

The Portuguese inquisition was terminated only in 1821 by the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Assembly of the Portuguese Nation."

Organization

[edit]Agents of the Inquisition

[edit]The inquisitors were the main officials and accumulated the functions of investigator and judge in the courts of the Holy Office.[35] Furthermore, the courts had an entire apparatus of bureaucratic officials and their own prisons where the accused were detained.[36] Finally, the so-called familiares – members of the Holy Office who were not part of the clergy, usually members of the nobility – were spread throughout the Portuguese territory, being able, among other things, to carry out arrests.[37]

Courts

[edit]In a first phase, six courts were organized in Portugal between 1536 and 1541: Évora, Lisbon, Tomar, Coimbra, Lamego and Porto.[38] These locations, combined with the appointment of bishops and local vicars as inquisitors, used the preexisting ecclesiastical network to quickly establish the institution. However, from 1548 onwards these courts were centralized in Lisbon and Évora, partly due to problems arising from the fact that the Holy Office had a very spread out structure and was an institution still in the process of formation, perhaps with financial problems. It was only after the 1560s, with the reestablishment of the Coimbra court and the founding of the Goa court, that the courts stabilized and took a more defined form.[39] Such forms continued without major changes until the decline of the Inquisition at the end of the 18th century.

The Court of the Holy Office accepted complaints of all types, including rumors, hunches and presumptions, made by anyone, regardless of the complainant's reputation or position. Anonymous denunciations were also accepted, if it seemed to the inquisitors that this was appropriate "to the service of God and the good of the Faith", just as reports obtained under torture were accepted.[40] The regulations stipulated, however, that prisoners should not appear in the autos de fé "showing signs of torture".[41]

A lawyer appointed by the Holy Office was just a ornament; he did not accompany defendants during interrogations and his role was often more to the detriment of the defendant than anything else.[42]

The most common accusations were mostly against crypto-judaism, but also against other numerous offences, such as crimes against morality, homosexuality, witchcraft, blasphemy, bigamy, luteranism, freemasonry, crypto-maometism, criticism of dogmas or the inquisition itself.[43]

Punishment methods

[edit]There was a strict policy on the part of the authorities to maintain religious order through the correction of offenders. The main forms of punishment were the galleys, forced labor, flogging, exiles, confiscations and, as a last resort, the death penalty by fire or garrote.[44][45] Exile consisted of the individual's exclusion from their social environment until their nature was "corrected" and could then provide "balance" for the nation. Under the pretext of salvation of the soul and following divine law, exile was nothing more than the removal of undesirables by the church and the state, forming part of the judicial gears of their power.[44][46]

Within the general framework of penalties applied, confiscation was one of the most feared weapons in the fight against heresy (or more particularly Judaism). It was carried out under a dual jurisdiction: that of the Judges of the Fisco, who carried out the seizures and executed the sentences, and that of the Inquisitors, who ordered the arrests and judged the cases. The arrest of the accused was followed by the seizure of their assets, which, after being inventoried, were placed in storage by the tax authorities, who managed them and could even sell them. This process was called sequestration. After the trial, if the defendant was acquitted, his assets would be returned; if convicted, they would be definitively seized and sold to the public. This second stage was called confiscation and forfeiture of assets. In concrete terms, however, once the assets had been preventively seized, they were practically lost for both the guilty and the innocent, so difficult was it to recover them; everything had been sold.[46]

Thus, the arrest was the start of the punishment and was almost always followed by the conviction. As this punishment was necessarily linked to sequestration, it could, according to Sónia Siqueira, "create the impression that it was the interest in the property that led to the conviction" of the accused when, in fact, only those who were almost convicted were imprisoned and therefore affected by sequestration. As for confiscations, they were based on a presumption of joint family guilt, which meant that entire families, deprived, had to live on charity, starving and deprived.[46] For the historian Hermano Saraiva, the confiscation of the fortunes of the New-Christians was the subject of "much interest", a possible source of revenue.[47] The New-Christians formed, for the most part, a middle class of capitalists and merchants, and were not well accepted by either the Old-Christian petty bourgeoisie or the nobility.[48]

The money raised by the confiscations was used to pay the costs of the Inquisition and its cumbersome machinery, but it was also given to the Crown. Although they were used to support the courts of the Holy Office, the confiscations subsidised much more, including fleet equipment and the state's war expenses.[46][44] However, historian António José Saraiva came to the conclusion that, although the confiscated assets legally belonged to the king, they were in fact administered and enjoyed by the inquisitors; after deducting the Inquisition's expenses – salaries, visits, trips, autos de fé, among others – what was left, little or nothing, was handed over to the Royal Treasury. Still according to A.J. Saraiva's conclusions, it is easy to understand why the Inquisition's coffers were always chronically empty. The Inquisition was a vehicle for distributing money and goods to its many members, a form of plundering, like war, albeit more bureaucratised.[49]

Modus operandi

[edit]Denunciations

[edit]The usual procedure began with the announcement of a period of grace, set out in an "Edict of Grace". In a chosen locality, visited by the inquisitors, the so-called heretics were asked to come forward, and denunciations were made; this was the basic method of finding suspected heretics.[50]

Many denounced themselves or confessed to alleged heresy for fear that a friend or neighbour might do so later. The terror of the Inquisition provoked a domino effect of denunciations.[51]

If they confessed within a "grace period" – usually 30 days – they could be accepted back into the church without penance. In general, the benefits offered by the edicts of grace to those who came forward spontaneously were forgiveness of the death penalty or life imprisonment and forgiveness of the penalty of confiscation of property, but they would have to denounce other people who had not come forward. Denouncing oneself as a heretic was not enough.[52]

Anyone suspected of knowing about someone else's heresy who did not make the obligatory denunciation would be excommunicated and then subject to prosecution as a "promoter of heresy". If the denouncer named other potential denouncers, they would also be summoned.[53]

The burden of justification remained with the accused. Denunciations were used by many as personal revenge against neighbours and relatives, or to eliminate rivals in business or commerce. The death penalty, applied by the secular arm (the state), was basically reserved for unrepentant heretics and those who had "relapsed" after nominal conversion to Catholicism.

All kinds of accusations were accepted by the Inquisition. It was foreseen that prison guards themselves could denounce and be witnesses against the accused.[54]

Interrogations

[edit]Based on denunciations, arrests were made by bailiffs or familiares, who were authorised to carry weapons and make arrests.[55]

The Inquisition's trials were secret and there was no possibility of appealing the decisions. The defendant was interrogated and pressed into confessing to the "crimes" attributed to him. The suspects did not know the charges against them or even the identity of the witnesses.[56]

Various methods were used to extract information. The first was the threat of death, usually including the choice of a confession or being burned at the stake. The second was imprisonment combined with food shortages. The third was visits from other people who had been tried, with the idea that they would encourage the accused to confess. After these methods, torture would be used,[57] or even the mere threat of it, in which the defendant was shown the various instruments used in it.

Over the years, the Inquisition produced various procedural manuals, veritable "instruction books" for dealing with the various types of heresy. The main text is Pope Innocent IV's own bull Ad Extirpanda of 1252, which in its thirty-eight laws details what should be done and authorises the use of torture.[58] Of the various manuals produced afterwards, some stand out: by Nicholas Eymerich, Directorium Inquisitorum, written in 1376; by Bernardo Gui, Practica inquisitionis heretice pravitatis, written between 1319 and 1323. Witches were not forgotten: the book Malleus Maleficarum ("the hammer of the witches"), written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer, deals with the subject. In Portugal, several "Regiments" (four) were written for use by the inquisitors, the first in 1552 at the behest of Cardinal Inquisitor Henry and the last in 1774, sponsored by the Marquis of Pombal. The Regulations of 1640 stipulated that each tribunal of the Holy Office should have a Bible, a compendium of canon and civil law, Eymerich's Directorium Inquisitorum, and Diego de Simancas's De Catholicis institutionibus.[59]

Torture

[edit]

Interrogations were sometimes followed by torture sessions. In Portugal, the Regiment of 1613, on how to proceed with defendants who were to be subjected to torture and how it was to be carried out, states: "... when the decision is made that the accused be subjected to torture, either because the crime has not been proven or because his confession is incomplete (...)". In other words, both the person against whom there was no evidence and the so-called diminuto (the one whose confession was imperfect) could be subjected to torture. Before the session, however, the accused was informed that if he died, broke a limb or lost consciousness during the torture, it would only be his fault, since he could have avoided the danger by confessing his offences without delay.[60]

After the bull Ad Extirpanda, authorising torture, but not at the hands of the clerics themselves, Pope Alexander IV in the bull Ut Negotium of 1256, allowed the inquisitors to absolve each other if they had incurred any "canonical irregularities in their important work". After the middle of the 13th century, torture had a secure place in the proceedings of the inquisition.[61][62][63]

The most common methods of torture were the strappado, in which the victim's arms were tied behind their back by ropes, and the interrogated person was then suspended in the air by a pulley and suddenly lowered a short distance to the ground;[64] and the rack, in its many variants, in which the body was stretched until it dislocated joints and rendered muscles useless.[60] Also used was the water torture, the famous waterboarding,[65] which later became better known for its use by the CIA at the beginning of the 21st century.

Before the start of a torture session, the interrogated person would be shown the instruments, which was often enough to compel their testimony.[65] The sessions were meticulously recorded in writing. A large number of these documents survive. Statements made during torture would, in theory, have to be repeated later, freely, and in a place far from the torture chamber, but in practice, those who recanted their confessions knew that they could be tortured again.[66] Cullen Murphy points the fact, well known by interrogators, that people will say anything under torture or even severe interrogation.[66] Historian Alexandre Herculano writes that any terrorized defendant would confess that he had swallowed the moon, if he was told to.[67]

Trials

[edit]It is possible to learn about Inquisition's procedures through its Regiments, in other words, through the institution's codes and procedural rules. There are four versions of the Regiments, up to the last one, the "reformed" one of 1774, which also provides for the legitimate use of torture and the carrying out of autos de fé.[68][69]

There is hardly one item in the whole Inquisitorial procedure that could be squared with the demands of justice; on the contrary, every one of its items is the denial of justice or a hideous caricature of it [...] its principles are the very denial of the demands made by the most primitive concepts of natural justice [...] This kind of proceeding has no longer any semblance to a judicial trial but is rather its systematic and methodical perversion.

After the previous phases of denunciations, arrests, interrogations and torture, the accusation was made by an official of the Holy Office, the Promoter, who acted as an agent of the Inquisition's public prosecution service.[71]

The instructions states that the Promotor shall draw up the libels of accusation in the name of Justice. He shall say that "since the defendant is a baptised Christian and as such obliged to hold and believe all that the Holy Mother Church of Rome holds, believes and teaches, he has done otherwise". And he will conclude his libel by asking that the defendant "be punished as a negative and pertinacious heretic, with all the rigour of law, and delivered to secular justice".[71]

There weren't as many accusations as facts, but as many accusations as the accusers. This was a process characteristic of the Inquisition. So, the same single fact reported under different circumstances by different witnesses, could be multiplied in many accusations.[72]

The defendant's lawyer was not chosen by the defendant, but appointed by the Inquisition. He was at the service of the Holy Office, and instructed to defend the defendant well and truly, but if by the course of the cause he was persuaded that the defendant was defending himself unjustly, he should give it up and come and declare it at the Mesa. The lawyer was therefore, after all, one more possible denouncer.[73]

Also, the so called lawyer had no access to the case file and only knew the libels and judgements communicated to the defendant; and he could not accompany him when he was called to interrogations or other proceedings.[74]

This was followed by the defendant's defence, which was based mainly on contradictions, that is, that the prosecution witnesses were his enemies, suspicious witnesses.[75]

The accused did not know who the informants were, and there was no means of cross-questioning witnesses who might have been perjurors, excommunicates, criminals or even accomplices. He knew no details of the charge and no appeal to a higher court was allowed.[56] In one of his books, the historian A. J.Saraiva points out the analogy with the Moscow trials in Stalin's time, or with the absurdity of Franz Kafka's The Trial.[76]

The final judgement was passed by majority vote at the Desk of the Holy Office.[77]

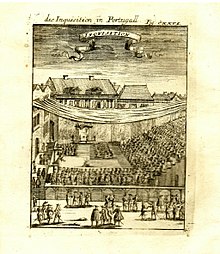

Autos de fé

[edit]

The auto de fé was the final step in the process, and included Mass, prayer, and a procession in which the convicts were paraded and then the sentences against them were read. Hundreds of penitents would be led in procession through the streets, their sentences pronounced before an audience of magnates, prelates, and many thousands of onlookers. The kings themselves might attend.[78][79]

Preparations began several weeks in advance, in time to build the scaffold and the amphitheatres, and to make the sanbenitos, a kind of penitential garment the condemned would wear at the auto de fé.[80]

An auto de fé was a ceremony of pomp and circumstance, a display of the power of the inquisitors.[81] At the same time, it was a popular feast, annual and expensive, and the people who attended brought snacks as if for a picnic.[82] The reading of the sentences could take all day.

The place of executions was never the same of the auto de fé. None of the inquisitors or Inquisitorial officials witnessed the executions, carried out by the “secular arm.” For example, at Lisbon, having been handed over to secular justice, the condemned were marched more than a kilometre from the site of the auto to the site of the executions.[83]

Executions

[edit]After the auto de fé ceremony, the victims were led to the stake. But before, they had been stripped of their sambenitos, that were placed on the walls of the churches to perpetuate the memory of their guilt.

The Inquisitors handed over the defendant to secular justice, begging it to “treat him benevolently and devoutly and not to proceed to the death sentence or the shedding of blood”. In reality, they were perfectly aware of the fate to which they were handing men and women. Also, in theory the civil magistrate was required to judge the defendants; in fact, however, he didn´t even have access to their trial records but he knew only the sentence and carried it out.[84]

Evidence was also collected against people who had already died—so, if their heresy was proved, their bodies were exhumed and burned to remove all trace of them.[84]

The condemned were asked if they wanted to die as Catholics. If the answer was yes, they were immediately put to death by garrotte on a pole. If the answer was "no", they were tied to a higher post, where there was a small wooden platform. In front of the excited crowd the executioner set fire to the pyre at the base of the stake. Lisbon riverside is frequently windy so the breeze would often deflect the flames. The victim was perched at such a high place above the pyre that the fire would not reach beyond his feet or legs. He was not choked but slowly grilled alive during one or two hours until dead. The victim’s screams made the crowd’s glee.[85]

Table of sentences

[edit]The archives of the Portuguese Inquisition are one of the best-preserved judicial archives of early modern Europe. Portuguese historian Fortunato de Almeida (1869–1933) gives the following statistics of sentences pronounced in the public ceremonies' autos de fé between 1536 and 1794:[86]

| Tribunal | Number of autos de fé with known sentences[87] | Executions in persona | Executions in effigie | Penanced | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lisbon | 248 (1540–1794) |

461 | 181 | 7,024 | 7,666 |

| Évora | 164 (1536–1781) |

344 | 163 | 9,466 | 9,973 |

| Coimbra | 277 (1541–1781) |

313 | 234 | 9,000 | 9,547 |

| Goa | 71 (1560–1773) |

57 | 64 | 4,046 | 4,167 |

| Tomar | 2 (1543–1544) |

4 | 0 | 17 | 21 |

| Porto | 1 (1543) |

4 | 21 | 58 | 83 |

| Lamego | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 763 | 1,183 (3.76%) |

663 (2.11%) |

29,611 (94.13%) |

31,457 (100%) |

These statistics are incomplete in terms of data for the Goa Tribunal. The list of autos de fé that Almeida cites was created by Inquisition officials in 1774; it is also fragmentary and does not cover the whole time of the organization's activity. [88]

According to Henry Charles Lea,[89] between 1540 and 1794, the courts of Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra and Évora burned 1,175 people alive, burned the effigies of another 633 and imposed punishments on 29,590 people. However, these figures may slightly underestimate the reality. It is also unknown how many victims died in the Inquisition's prisons as a result of illness, poor conditions and mistreatment; prisons could last for months or even years awaiting confirmation of the "crimes".[90][91][92]

Opposition and resistance

[edit]Father António Vieira (1608-1697), a Jesuit, philosopher, writer and orator, was one of the most important opponents of the Inquisition. Arrested by the Inquisition for "heretical, reckless, ill-sounding and scandalous propositions" in October 1665, imprisoned until December 1667, after his release he went to Rome.[93] Under the Inquisitorial sentence, he was forbidden to teach, write or preach.[94] Only perhaps Vieira's prestige, his intelligence and his support among members of the royal family saved him from greater consequences.[95]

He is thought to have been the author of the famous anonymous writing "Notícias Recônditas do Modo de Proceder a Inquisição de Portugal com os seus Presos", which reveals a great knowledge of the inner workings of the Inquisitorial mechanism, and which he delivered to Pope Clement X in favour of the cause of the persecuted of the Inquisition.[96]

In Rome, where he spent six years, he was leading an anti-inquisition movement; meanwhile, in 1673, the Inquisitors were persecuting his relatives in Portugal.[97] In addition to his humanitarian objections, there were others: Vieira realised that a mercantile middle class (the New Christians) was being attacked that would be sorely missed in the country's economic development. [98]

Archives

[edit]Most of the original documentation from the Portuguese Inquisition courts is preserved in Lisbon. However, the majority of the Goa archives (16,202 trial records) were destroyed and the rest were transported to Brazil, where they can be found in the National Library in Rio de Janeiro.[99]

Some minor gaps concern the tribunals, i.e. there is no usable data on around fifteen autos de fé celebrated in Portugal between 1580 and 1640,[100] while the records of the short-lived tribunals in Lamego and Porto (both active from 1541 until c. 1547) have yet to be studied.[88]

Given the nature of the Inquisition, archives and documentation can be found in several countries, including Belgium[101] and the United States.

In 2007, the Portuguese Government initiated a project to make available online by 2010 a significant part of the archives of the Portuguese Inquisition (more than 35,000 processes) currently deposited in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, the Portuguese National Archives.[102]

In December 2008, the Jewish Historical Society of England (JHSE) published the Lists of the Portuguese Inquisition in two volumes: Volume I Lisbon 1540–1778; Volume II Évora 1542–1763 and Goa 1650–1653. The original manuscripts, assembled in 1784 and entitled Collecção das Noticias, were once in the Library of the Dukes of Palmela and are now in the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. The texts are published in the original Portuguese, transcribed and indexed by Joy L. Oakley. They represent a unique picture of the whole range of the Inquisition's activities and a primary source for Jewish, Portuguese, and Brazilian historians and genealogists.

Historical research

[edit]As early as the first quarter of the 18th century, it was recognised the scientific need to carry out a historical study of the Portuguese Inquisition. So, at the conference of the Royal Academy of Portuguese History on 5 January 1721, Father Pedro Monteiro, of the Dominican Order, was entrusted with the task of a study of the Inquisition. The study was initiated but never completed. No one ever wrote about the issue, there were no previous study to follow. The Inquisition was still active and demanded secrecy. Pedro Monteiro, after many years of delays and self censorship, gave up.[103]

After that, a Historia dos principais actos e procedimentos da Inquisição em Portugal, was published around 1847 anonymously, but later was attributed to Antonio Joaquim Moreira (and José Lourenço de Mendonça). The original text was part of a general História de Portugal (1842, Tomo IX) translated from a book by german historian Henrique Schaeffer, and was missing (suppressed or ripped) from the Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa existing copy.[104][105]

Only after 1854 till 1859 Alexandre Herculano wrote História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal one of his most famous books, a masterly work . According to his own words, it is a study of "the twenty years of struggle between King John III and his Hebrew subjects, he to definitively establish the Inquisition, they to obstruct it".[106]

In more recent times in Portugal, in the 1960s, PIDE (the political police of the right wing Estado Novo) considered banning the António José Saraiva's work on the Portuguese Inquisition. According to the officer who analysed the book, it didn't make sense to ban it, then in its third edition, but rather to prevent it from being publicised; moreover, the work was found less severe than Alexandre Herculano's, which was much older, on the same subject.[107]

Current stance of the Catholic Church

[edit]Reflection on the inquisitorial activity of the Catholic Church began in earnest in the run-up to the Great Jubilee of 2000, at the initiative of John Paul II, who called for repentance from "examples of thought and action that are in fact a source of anti-testimony and scandal".

On 12 March 2000, during the celebration of the Jubilee, the Pope John Paul II, on behalf of the entire Catholic Church as well as all Christians, apologised for these acts and in general for several others.[108][109] He asked for forgiveness for seven categories of sins: general sins; sins "in the service of truth"; sins against Christian unity; sins against the Jews; against respect for love, peace and cultures; sins against the dignity of women and minorities; and against human rights. While this apology was welcomed by many Jewish leaders and others, Bishop Alessandro Maggiolini criticized the apology.[109]

Several critics, including prominent Jews, deemed John Paul II's apology insufficient. They brought up, among other things, the beatification, at the same time, of Pope Pius IX, notorious for his anti-Semitic views and for the kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara, a six-year-old taken by force from his Jewish family.[110]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. XXXIII.

- ^ Fernandes, Dirce Lorimier (2004). A inquisição na América durante a união ibérica (1580–1640) (in Portuguese). Arke.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Kayserling, Meyer (1971). História dos judeus em Portugal (in Portuguese). Pioneira. p. 112.

- ^ Kayserling 1971, p. 114.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Marcocci, Giuseppe (2011). A fundação da Inquisição em Portugal: um novo olhar (in Portuguese). Lusitania Sacra (23 Janeiro–Junho). pp. 17–40.

- ^ a b Saraiva 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, p. 42.

- ^ a b Saraiva 1969, pp. 62–65.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 28–40.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Fromont, Cécile (June 2020). Jain, Andrea R. (ed.). "Paper, Ink, Vodun, and the Inquisition: Tracing Power, Slavery, and Witchcraft in the Early Modern Portuguese Atlantic". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 88 (2). Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Academy of Religion: 460–504. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfaa020. eISSN 1477-4585. ISSN 0002-7189. LCCN sc76000837. OCLC 1479270.

- ^ Corrêa Teixeira, Rodrigo. "A história dos ciganos no Brasil" (PDF). Dhnet.org.br. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ Paiva, Jose P. (30 November 2016). "Philip IV of Spain and the Portuguese Inquisition (1621–1641)". Journal of Religious History. 41 (3): 364–385. doi:10.1111/1467-9809.12406. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Roth, Norman (1994), Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in medieval Spain : cooperation and conflict, pp.79–90, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-09971-5

- ^ Anthony D’Costa (1965). The Christianisation of the Goa Islands 1510–1567. Bombay: Heras Institute.

- ^ Delgado Figueira, João (1623). Listas da Inquisição de Goa (1560–1623). Lisbon: Biblioteca Nacional.

- ^ Prabhu, Alan Machado (1999). Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians. I.J.A. Publications. ISBN 978-81-86778-25-8.

- ^ de Almeida, Fortunato (1923). História da Igreja em Portugal, vol. IV. Porto: Portucalense Editora.

- ^ The Imperio in the Azores – The Five Senses in Rituals to the Holy Spirit, Author: Maria Santa Montez, Instituto de Sociologia e Etnologia das Religioes, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa; page 171

- ^ [1]BREVE NOTÍCIA DAS FESTAS DO IMPERADOR E BODO DO DIVINO ESPÍRITO SANTO, Padre Alberto Pereira Rei, Introdução: Manuel Gandra

- ^ Descrição: Colectânea das principais Censuras e Interditos visando os Impérios do Divino Espírito Santo, Autor: Manuel J. Gandra – Boletim Trimestal do Centro Ernesto Soares de Iconografia e Simbólica – Outono 2009 "Colectânea das principais Censuras e Interditos visando os Impérios do Divino Espírito Santo (PDF) | ..:: Livraria Virtual CESDIES ::". Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Inquisição E Tradição Esotérica: O Neoprofetismo e a Nova Gnose, Da Cosmovisão Rosacruz Aos Mitos Ocultos De Portugal, Acção E Reacção No Colonialismo E Ex-Colonialismo Do Império Português – X – Culto do Espírito Santo – Profetismo – V Império – Sebastianismo – XI – Brasil e Goa, António de Macedo, Hugin Editores, Lisboa, 2003 [2]

- ^ The Imperio in the Azores – The Five Senses in Rituals to the Holy Spirit, Maria Santa Montez

- ^ Descrição: Colectânea das principais Censuras e Interditos visando os Impérios do Divino Espírito Santo, Manuel J. Gandra

- ^ Maia, Moacir Rodrigo de Castro (2022). De reino traficante a povo traficado: A diáspora dos courás do golfo do Benim para Minas Gerais (América Portuguesa, 1715–1760) (PDF). Rio de Janeiro: Arquivo Nacional. p. 19. ISBN 9788570090034.

- ^ Martins, Ana Margarida (2019). "Teresa Margarida da Silva Orta (1711–1793): A Minor Transnational of the Brown Atlantic". Portuguese Studies. 35 (2): 136–53. doi:10.5699/portstudies.35.2.0136. ISSN 0267-5315. JSTOR 10.5699/portstudies.35.2.0136. S2CID 213802402.

- ^ Azevedo 1921, p. 263, 264.

- ^ Lea 1907, p. 285.

- ^ a b Azevedo 1922, p. 285.

- ^ "Gabriel Malagrida". New Advent. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b Maxwell 1995, pp. 79–82.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 379.

- ^ Lima, Lana L.G. (November 1999). "O Tribunal do Santo Ofício da Inquisição: o suspeito é o culpado". Revista de Sociologia e Politica (13). doi:10.1590/S0104-44781999000200002.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 174.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 49, 148, 174.

- ^ Bethencourt 2000, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Bethencourt 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 53.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 38, 45, 57, 58.

- ^ Novinsky, Anita (1982). A Inquisição (in Portuguese). Editora Brasiliense. pp. 49–52, 56.

- ^ a b c Pieroni, Geraldo (1997). "Os excluídos do Reino: A Inquisição Portuguesa e o degredo para o Brasil-Colônia". Textos de História. 5 (2): 23–40.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d Siqueira, Sônia A. (1970). "A Inquisição Portuguesa e os confiscos". Revista de História (in Portuguese). 40 (82): 323–340. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9141.rh.1970.128993. ISSN 2316-9141.

- ^ Saraiva, José Hermano (1986). História concisa de Portugal (10th ed.) (in Portuguese). Publicações Europa-América. p. 182.

- ^ Marques, A.H. de Oliveira (2015). Breve História de Portugal (9th ed.) (in Portuguese). Editorial Presença. p. 268.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 184–187.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 140.

- ^ Burman, Edward (1984). The Inquisition: The Hammer of Heresy. Dorset Press. p. 143.

- ^ Bethencourt, Francisco (1997). La Inquisition en la Epoca Moderna – España, Portugal e Italia Siglos XV-XIX (in Spanish). Akal Ediciones. pp. 202–204.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 47-48.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 49.

- ^ a b Ullmann 2003, p. 166.

- ^ Thomsett, Michael (2010). The Inquisition : a History. McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers. p. 31.

- ^ "SS Innocentius IV – Bulla 'Ad_Extirpanda' [AD 1252-05-15]" (PDF). Documenta Catholica Omnia. 1252.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 43-45.

- ^ a b Saraiva 2001, p. 53-54.

- ^ Pegg, Mark Gregory (2001). The Corruption of Angels – The great Inquisition of 1245–1246. Princeton University Press. p. 32.

- ^ Peters, Edward (1996). Torture (Expanded Edition). University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 65.

- ^ Lea, Henry Charles (1888). A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Innes, Brian (2016). The History of Torture. Amber Books. p. 71.

- ^ a b Baião 1919, p. 254-259.

- ^ a b Murphy, Cullen (2012). God's Jury : The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. p. 89.

- ^ Herculano 1926, p. 557.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Freitas, Jordão de (1916). O Marquez de Pombal e o Santo Oficio da Inquisição (in Portuguese). Sociedade Editora José Bastos. pp. 71–85.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 61,62.

- ^ a b Saraiva 1969, p. 90.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, pp. 91, 92.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, p. 93.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, p. 94.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, pp. 77, 94, 95.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, pp. 11, 142–144.

- ^ Saraiva 1969, p. 77.

- ^ Murphy 2013, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Kirsch 2008, pp. 84, 8, 85.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 104.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 100–104, 114.

- ^ Novinsky . pp. 66–68, Anita (1982). A Inquisição (in Portuguese). Editora Brasiliense. pp. 66–68.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b Deane, Jennifer Kolpacoff (2011). A History of Medieval Heresy and Inquisition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 114.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 110–111.

- ^ F. Almeida: História da Igreja em Portugal, vol. IV, Oporto 1923, Appendix IX (esp. p. 442).

- ^ In the parentheses the dates of the first and last registered auto da fé

- ^ a b A.J. Saraiva, H.P. Salomon, I.S.D. Sassoon: The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536–1765. BRILL, 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Lea 1907, pp. 310–311.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 74.

- ^ Killgrove, Kristina (18 August 2015). "Skeletons Of Jewish Victims Of Inquisition Discovered In Ancient Portuguese Trash Heap". Forbes. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Rocha, Catarina (9 September 2015). "Ossos de antiga prisão de Évora dão voz às vítimas da Inquisição". PÚBLICO (in Portuguese). Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "António Vieira Portuguese author and diplomat". Britannica. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Padre António Vieira nos cárceres da Inquisição". Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Paiva, José Pedro (2011). "Revisitar o processo inquisitorial do padre António Vieira". Lusitania Sacra.

- ^ Vieira, António (1821). Noticias reconditas do modo de proceder a Inquisição de Portugal com os seus prezos (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 177.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 147, 152, 159, 160, 197, 208.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, pp. 345, 346.

- ^ Henry Charles Lea, A History of the Inquisition of Spain, vol. 3, Book 8, p. 264 and 273.

- ^ Saraiva 2001, p. 37.

- ^ Papéis Inquisição na Net com apoio de mecenas [Archives of the Inquisition will be available online] (in Portuguese), Portugal: Sapo, 12 July 2007, archived from the original on 17 July 2007.

- ^ Baião 1906, p. 6-9.

- ^ Baião 1906, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Mendonça 1980, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Baião 1906, p. 9.

- ^ "CENSURA – RELATÓRIO Nº 7603 (20 DE DEZEMBRO DE 1965) / Nº 8527 (E DE JULHO DE 1969 / RELATIVOS A "INQUISIÇÃO PORTUGUESA" DE ANTÓNIO JOSÉ SARAIVA". Ephemera - Biblioteca e Arquivo de José Pacheco Pereira. Retrieved 20 January 2024.

- ^ John Paul II (12 March 2000). "12 March 2000, Day for pardon". Vatican. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ a b Carroll, Rory (13 March 2000). "Pope says sorry for sins of church". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (9 March 2000). "Pope berated for beatifying child-snatching Pius IX". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077.

Bibliography

[edit]- Azevedo, João Lúcio de (1921). Historia dos Christãos Novos Portugueses (in Portuguese). Livraria Clássica Editora.

- Azevedo, João Lúcio de (1922). O Marquês de Pombal e a sua época (in Portuguese). Anuario do Brasil.

- Baião, António (1906). A Inquisição em Portugal e no Brazil: Subsídios para a sua História (in Portuguese). Arquivo Historico Português.

- Baião, António (1919). Episódios dramáticos da inquisição portuguesa Volume II (in Portuguese). Alvaro Pinto Editor.

- Bethencourt, Francisco (2000). História das Inquisições Portugal, Espanha e Itália Séculos XV – XIX (in Portuguese). Companhia das Letras.

- Disney, Anthony (2009). A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire Volume One. Cambridge University Press.

- Herculano, Alexandre (1900). História da Origem e Estabelecimento da Inquisição em Portugal (in Portuguese).

- Herculano, Alexandre (1926) – "History Of The Origin And Establishment Of The Inquisition In Portugal" translation of 1926 by John C. Branner

- Kirsch, Jonathan (2008). The Grand Inquisitor’s Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of God. Harper Collins.

- Lea, Henry Charles (1907). A History of the Inquisition of Spain, Vol. 3. The MacMillan Company.

- Maxwell, Kenneth (1995). Pombal paradox of the Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press.

- Mendonça, José L. (1980). História da Inquisição em Portugal. Círculo de Leitores.

- Murphy, Cullen (2013). God's juryThe Inquisition and the making of the modern world. Penguin Books.

- Poettering, Jorun, Migrating Merchants. Trade, Nation, and Religion in Seventeenth-Century Hamburg and Portugal, Berlin, De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2019.

- Saraiva, António José (1969). Inquisição e Cristãos-Novos (in Portuguese) (4th ed.). Editorial Inova.

- Saraiva, António José (2001). The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians. Translated by Salomon, Herman Prins; Sassoon, Isaac S. D. Leiden: Brill.

- Ullmann, Walter (2003). A Short History of the Papacy in the Middle Ages. Routledge.

- Vieira, Padre António (1821). Notícias Recônditas do Modo de Proceder a Inquisição de Portugal com os seus Presos: Informação que ao Pontífice Clemente X deu o P. Antonio Vieira (in Portuguese). Imprensa Nacional.

Further reading

[edit]- Aufderheide, Patricia. "True Confessions: The Inquisition and Social Attitudes in Brazil at the Turn of the XVII Century." Luso-Brazilian Review 10.2 (1973): 208–240.

- Beinart, Haim. "The Conversos in Spain and Portugal in the 16th to 18th Centuries." In Moreshet Sepharad: The Sephardi Legacy, 2 vols., edited by Haim Beinart, II.43–67. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, 1992.

- Higgs, David. "The Inquisition in Brazil in the 1790s." communication du séminaire Late Colonial Brazil, University of Toronto (1986).

- Higgs, David. "Tales of two Carmelites: inquisitorial narratives from Portugal and Brazil." Infamous desire: male homosexuality in colonial Latin America (2003): 152–167.

- Jobim, L.C. "An 18th-century denunciation of the Inquisition in Brazil." Estudios Ibero-americanos 13.2 (1987) pp. 195–213.

- Marcocci, Giuseppe. "Toward a History of the Portuguese Inquisition Trends in Modern Historiography (1974–2009)." Revue de l'histoire des religions 227.3 (2010): 355–393.

- Mocatta, Frederic David. The Jews of Spain and Portugal and the Inquisition. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1877.

- Mott, Luiz. "Crypto-sodomites in colonial Brazil." Pelo Vaso Traseiro: Sodomy and Sodomites in Luso-Brazilian History (Tucson: Fenestra Books, 2007a) (2003): 168–96.

- Myscofski, Carole. "Heterodoxy, Gender, and the Brazilian Inquisition: Patterns in Religion in the 1590s." (1992).

- Novinsky, Anita. "Marranos and the Inquisition: On the Gold Route in Minas Gerais, Brazil." The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West 1400 (2001): 1800.

- Novinsky, Anita. "Padre Antonio Vieira, the inquisition, and the Jews." Hîstôry¯ a yêhûdît= Jewish history 6.1–2 (1992): 151–162.

- Paiva, José P. "Philip IV of Spain and the Portuguese Inquisition (1621–1641)." Journal of Religious History (2016).

- Pieroni, Gedaldo. "Outcasts from the kingdom: the Inquisition and the banishment of New Christians to Brazil." The Jews and the expansion of Europe to the west, 1450–1800 (2000): 242–251.

- Pulido Serrano, Juan Ignacio. "Converso Complicities in an Atlantic Monarchy: Political and Social Conflicts behind the Inquisitorial Persecutions." In The Conversos and Moriscos in Late Medieval Spain and Beyond, Volume Three: Displaced Persons, edited by Kevin Ingram and Juan Ignacio Pulido Serrano, 117–128. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

- ---. "Plural Identities: The Portuguese New Christians." Jewish History 25 (2011): 129–151.

- Ray, Jonathan. After Expulsion: 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

- Roth, Norman. Conversos, Inquisition, and the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain [1995]. 2nd ed. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002.

- Rowland, Robert. "New Christian, Marrano, Jew." In The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450–1800, edited by Paolo Bernardini and Norman Fiering, 125–148. New York: Berghahn Books, 2001.

- Santos, Maria Cristina dos – "Betrayal: A Jesuit in the service of Dutch Brazil processed by the Inquisition." (2009)

- Santos, Vanicléia Silva. "Africans, Afro-Brazilians and Afro-Portuguese in the Iberian Inquisition in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries." African and Black Diaspora 5.1 (2012): 49–63.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. "Luso-Spanish Relations in Hapsburg Brazil, 1580–1640." The Americas 25.01 (1968): 33–48.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. "Inquisition, catalog of the accused-Sources for a history of Brazil, 18th century (Portuguese)-Novinsky, A." (1996): 114–134.

- Siebenhüner, Kim. "Inquisitions." Translated by Heidi Bek. In Judging Faith, Punishing Sin: Inquisitions and Consistories in the Early Modern World, edited by Charles H. Parker and Gretchen Starr-LeBeau, 140–152. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Soyer, François. The Persecution of the Jews and Muslims of Portugal: King Manuel I and the End of Religious Tolerance (1496–7). Leiden: Brill, 2007.

- Stols, Eddy. "Dutch and Flemish Victims of the Inquisition in Brazil." Essays on Cultural Identity in Colonial Latin America: 43–62.

- Wadsworth, James E. "In the name of the Inquisition: the Portuguese Inquisition and delegated authority in colonial Pernambuco, Brazil." The Americas 61.1 (2004): 19–54.

- Wadsworth, James E. "Jurema and Batuque: Indians, africans, and the inquisition in colonial northeastern Brazil." History of religions 46.2 (2006): 140–162.

- Wadsworth, James E. "Children of the Inquisition: Minors as Familiares of the Inquisition in Pernambuco, Brazil, 1613–1821." Luso-Brazilian Review 42.1 (2005): 21–43.

- Wadsworth, James E. Agents of orthodoxy: honor, status, and the Inquisition in colonial Pernambuco, Brazil. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006.

- Walker, Timothy. "Sorcerers and folkhealers: africans and the Inquisition in Portugal (1680–1800)." (2004).

- Wiznitzer, Arnold. Jews in Colonial Brazil. New York: Columbia University Press, 1960.

- Wiznitzer, Arnold. "The Jews in the Sugar Industry of Colonial Brazil." Jewish Social Studies (1956): 189–198.

External links

[edit]- Index of the court proceedings and other documents of the Portuguese Inquisition (in Portuguese)

- Lists of the Portuguese Inquisition, in two volumes: Volume I Lisbon 1540–1778; Volume II Evora 1542–1763 and Goa 1650–1653.

- JHSE Publications