John Colter

John Colter | |

|---|---|

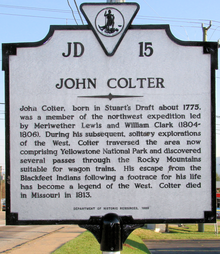

John Colter historical marker, located in Stuarts Draft, Augusta County, Virginia | |

| Born | c.1770-1775 Stuarts Draft, Augusta County, Virginia Colony, British North America, British Empire, present-day Stuarts Draft, Augusta County, Virginia |

| Died | May 7, 1812 or November 22, 1813 (aged 37-43) Sullen Springs, St. Louis, Missouri, present-day St. Louis, Missouri |

| Cause of death | jaundice |

| Resting place | Miller's Landing, Franklin County, Missouri, present-day New Haven, Franklin County, Missouri |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | John Coulter, John Coalter |

| Occupation(s) | frontiersman, soldier, fur trapper |

| Employer(s) | U.S. Government, self employed |

| Spouse | Sallie Loucy |

| Children | Hiram Jefferson Colter |

| Parent(s) | Joseph Colter and Ellen Shields |

John Colter (c.1774 – May 7, 1812 or November 22, 1813) was a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806). Though party to one of the more famous expeditions in history, Colter is best remembered for explorations he made during the winter of 1807–1808, when he became the first known person of European descent to enter the region which later became Yellowstone National Park and to see the Teton Mountain Range. Colter spent months alone in the wilderness and is widely considered to be the first known mountain man.[1]

Early years

John Colter was born in Stuarts Draft, Augusta County, Virginia Colony, British North America, British Empire, sometime between 1770 and 1775, based off assumptions by his family.[2] The Colter family patriarch Micajah Coalter is believed to have migrated from Ireland in 1700. There is some debate as to which variation of the family name, Coalter, Coulter, or Colter, is correct and the issue was further convoluted by Captain William Clark utilizing all three spelling variations during his daily journals. It is unknown whether or not Colter was literate and knew how to write. Two signatures possessed by the Missouri State Historical Society assert that the proper spelling of the family name was "Colter" and that Colter was at least able to write his own name.[2] Sometime around 1780, the Colter family moved west and settled near present-day Maysville, Kentucky. As a young man Colter may have served as a ranger under Simon Kenton.[3] He was 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) tall.[4] The outdoor skills he had developed from this frontier lifestyle impressed Meriwether Lewis, and on October 15, 1803, Lewis offered Colter the rank of private and a pay of five dollars a month when he was recruited to join what became the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

With Lewis and Clark

Colter, along with George Shannon, Patrick Gass and dog Seaman all joined the expedition while Lewis was waiting for the completion of their vessels in Pittsburgh and nearby Elizabeth, Pennsylvania. Prior to the expedition, leaving their basecamp in Pittsburgh, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were away from the main party, securing last minute supplies and making other preparations, leaving Sergeant John Ordway in charge. A group of recruits including Colter disobeyed orders from Ordway. Upon hearing of this infraction Lewis confined Colter and the others to ten days in the base camp.[5] Soon thereafter, Colter was court-martialed after threatening to shoot Ordway. After a review of the situation, Colter was reinstated after he offered an apology and promised to reform.[6]

During the expedition Colter was considered to be one of the best hunters in the group, and was routinely sent out alone to scout the surrounding countryside for game meat.[6] Colter was often trusted with responsibilities that went beyond hunting and woodsman activities. He was instrumental in helping the expedition find passes through the Rocky Mountains. In one instance, Colter was handpicked by Clark to deliver a message to Lewis, waylaid at a Shoshone camp, concerning the impracticability of following a route along the Salmon River. In another instance he was charged with retracing a route in the Bitterroot Mountains to recover lost horses and supplies, and not only returned with some of the recovered resources and horses, but also retrieved deer to gift the hospitable Nez Perce tribes and strengthen sick corp members.[2] Colter was also noted by Lewis for his ability to barter with various tribes, an attribute which may have led to his later role with Manuel Lisa. During the expedition Colter never appeared on sick lists, suggesting very advantageous health. He was often one of the few hunters allowed to leave the camp during points of illness and recuperation, proving Lewis and Clark’s trust in him. Another major contribution Colter made to the Corps of Discovery was providing the expedition with the means to swiftly descend the Bitterroot Mountains, allowing access to the Snake River, Columbia River and subsequently, the Pacific Ocean. While hunting far ahead of the main party, Colter encountered three Tushepawe Flatheads. Through non-verbal peace symbols and communication, Colter was able to dissuade the Flatheads to abandon their search for two Shoshones who had stolen twenty three head of horses, and accompany him to the expedition’s camp.[2] One of the young Flatheads agreed to act as the party’s guide down the mountains and through Flathead country, a great advantage in challenging and unfamiliar terrain plagued by a scarcity of game. Once at the mouth of the Columbia River, Colter was among a small group selected to venture to the shores of the Pacific Ocean, as well as explore the seacoast north of the Columbia into present-day Washington state.[7]

After traveling thousands of miles, in 1806 the expedition returned to the Mandan villages in present-day North Dakota. There, they encountered Forest Hancock and Joseph Dickson, two frontiersmen who were headed into the upper Missouri River country in search of furs. On August 13, 1806, Lewis and Clark permitted Colter to be honorably discharged almost two months early so that he could lead the two trappers back to the region they had explored.[8] Upon his discharge, Colter had earned payment for 35 months and 26 days, totaling $179.33 1/3rd dollars.[2] However, a discrepancy in the books provided Colter with payment for the two months he had skipped to accompany Hancock and Dickson trapping. However, this over-payment may have been justified by Colter’s significant work ethic and personal praise by Thomas Jefferson himself. However, in 1807, Colter’s settlement was retracted after Congress passed a mandate supplying all members of the Corps of Discovery with doubled wages and land grants of 320 acres. Lewis personally took responsibility for Colter’s reparations, and following Lewis’ death and Colter’s subsequent return to St. Louis, a court decided Colter was owed an amount of $377.60.

With Hancock and Dixon

Colter, Hancock, and Dixon ventured into the wilderness with 20 beaver traps, a two-year supply of ammunition, and numerous other small tools gifted to them by the expedition such as knives, rope, hatchets, and personal utensils.[2] The exact route of the trapping party is not known. However, it is speculated that unfriendly Blackfeet in the region of the Lower Missouri and a lack of horses forced the company to seek their fortunes in the tributaries of the less-prosperous Yellowstone Valley, a region inhabited by the friendlier Crows. However, the dangers of the narrow and rapid Yellowstone River, and the absence of game may explain the quick dissolution of the trapping party. After reaching a point where the Gallatin, Jefferson and Madison Rivers meet, known today as Three Forks, Montana, the trio managed to maintain their partnership for only about two months. There is much speculation as to where the party, at that point only consisting of Colter and Hancock following a falling out with Dixon, spent the winter of 1806-1807.[9] However, Wyoming historian J.K. Rollinson asserted in a personal letter that he had met the stepson of one of Colter’s companions, mostly likely Hancock’s as Dixon is known to have left the region for Wisconsin in 1827.[2] This stepson, Dave Fleming, accompanied his stepfather on a hunting trip to Clark’s Fork Canyon as a boy, and was informed that his stepfather had made camp in this exact spot while trapping with Colter many years earlier. Fleming reportedly remembered and passed on this detail as his stepfather asserted that during winter of 1806-1807, Colter had grown restless with taking shelter and ascended the canyon into the Sunlight Basin of modern-day Wyoming, which would make him the first known white man to have ever entered this region.[2] Colter headed back toward civilization, in 1807, and was near the mouth of the Platte River, when he encountered Manuel Lisa, a founder of the Missouri Fur Trading Company, who was leading a party that included several former members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, towards the Rocky Mountains. Among the band were George Drouillard, John Potts, and Peter Wiser. Colter once again decided to return to the wilderness, even though he was only a week from reaching St. Louis. At the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn Rivers, Colter helped build Fort Raymond, and was later sent by Lisa to search out the Crow Indian tribe to investigate the opportunities of establishing trade with them.[6]

Yellowstone, Grand Teton and Jackson Hole

Colter left Fort Raymond in October, 1807 with a pack weighing roughly thirty five pounds (not including his rifle and ammunition,) and traveled over five hundred miles to establish trade with the Crow nation. Over the course of the winter, he explored the region that later became Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Colter reportedly visited at least one geyser basin, though it is now believed that he most likely was near present-day Cody, Wyoming, which at that time may have had some geothermal activity to the immediate west.[10] Colter probably passed along portions of the shores of Jackson Lake after crossing the Continental Divide near Togwotee Pass or more likely, Union Pass in the northern Wind River Range. Colter then explored Jackson Hole below the Teton Range, later crossing Teton Pass into Pierre's Hole, known today as the Teton Basin in the state of Idaho.[10] After heading north and then east, he is believed to have encountered Yellowstone Lake, another location in which he may have seen geysers and other geothermal features. Colter then proceeded back to Fort Raymond, arriving in March or April 1808. Not only had Colter traveled hundreds of miles, much of the time unguided, he did so in the dead of winter, in a region in which nighttime temperatures in January are routinely −30 °F (−34 °C).

Colter arrived back at Fort Raymond and few believed his reports of geysers, bubbling mudpots and steaming pools of water. His reports of these features were often ridiculed at first, and the region was somewhat jokingly referred to as "Colter's Hell". The area Colter described is now widely believed to be immediately west of Cody, Wyoming, and though little thermal activity exists there today, other reports from around the period when Colter was there also indicate observations similar to those Colter had originally described. The exact location of Colter’s Hell remains partially contested, as the moniker could have been applied to several different areas prone to geothermic activity. It is commonly believed that Colter’s Hell referred to the region of the Stinking Water, now known as the Shoshone River, particularly the section running through Cody.[2] The river’s original title was thanks to presence of Sulfur in the surrounding area. His detailed exploration of this region is the first by a white man of what later became the state of Wyoming.

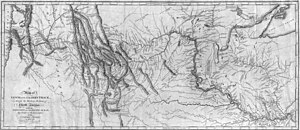

Colter's Route

It is not known if Colter produced his own crude map that informed Clark’s version or if the details were simply dictated to Clark by Colter following his return to St. Louis after a six-year absence. Colter’s Route was included in a version of Clark’s map, titled “A Map of Lewis and Clark’s Track Across the Western Portion of North America from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean,” which was published in 1814. However, Clark’s original field sketches, drawn on numerous separate sheets that traced the flows of principle rivers as opposed to traditional rectangular or square maps, were shown to President Jefferson in 1807 and did not include Colter’s Route, as he was still traveling at the time.[2] A version of these original field maps were produced in 1810 by Clark and Nicholas Biddle so that inaccurate recordings of latitude and longitude could be corrected by astronomer and mathematician, Dr. Ferdinand Hassler. This 1810 manuscript provided the details of Colter’s Route that were published in 1814. Several unexplained geographical discrepancies were printed on the 1814 map, including the Big Horn Mountains and Basin being drawn about two times too large, an error believed to be Clark’s.[2] The nature behind these discrepancies eludes historians, as Clark had not only his own personal information of the region but information from George Drouillard and John Colter as well. It is likely that Colter never saw Clark’s full field maps, as another major discrepancy places Colter’s starting point at the midsection of Pryor Creek, as opposed to only geographically likely departing point at the mouth of the Big Horn River. The inaccuracies that plague the 1814 map’s details of the area between Manuel’s Fort on the Yellowstone and the likely location of Colter’s Hell have fueled much of the scholarly disagreements surrounding Colter's Route.[2]

Colter's Run

The following year, Colter teamed up with John Potts, another former member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, once again in the region near Three Forks, Montana. In 1808, Colter and Potts set out from Fort Raymond once more to negotiate trade agreements with local nations. While leading a group of eight hundred Flathead and Crow Indians back to the trading fort, Colter's party was attacked by a mass of Blackfeet numbering over fifteen-hundred.[9] The Flatheads and Crows managed to force the Blackfeet into retreat, but Colter suffered a leg wound from either a bullet or arrow. However, this wound was non-serious as Colter quickly recuperated and left Fort Raymond with Potts once more the following year. In 1809, another altercation with the Blackfeet resulted in John Potts' death and Colter's capture. While going by canoe up the Jefferson River, Potts and Colter encountered several hundred Blackfeet who demanded they come ashore. Colter went ashore and was disarmed and stripped naked. When Potts then refused to come ashore he was shot and wounded. Potts in his turn shot one of the Indian warriors and died riddled with bullets fired by the Indians on the shore. His body was brought ashore and hacked to pieces. After a council, Colter was motioned, told in Crow to leave, and encouraged to run. It soon became apparent that he was running for his life pursued by a large pack of young braves. A fast runner, after several miles the still-naked Colter was exhausted and bleeding from his nose but far ahead of most of the group with only one assailant still close to him.[11] He then managed to overcome the lone man:

Again he turned his head, and saw the savage not twenty yards from him. Determined if possible to avoid the expected blow, he suddenly stopped, turned round, and spread out his arms. The Indian, surprised by the suddenness of the action, and perhaps at the bloody appearance of Colter, also attempted to stop; but exhausted with running, he fell whilst endeavouring to throw his spear, which stuck in the ground, and broke in his hand. Colter instantly snatched up the pointed part, with which he pinned him to the earth, and then continued his flight.

Colter got a blanket from the Indian he had killed. Continuing his run with a pack of Indians following he reached the Madison River, five miles (eight km) from his start, and, hiding inside a beaver lodge, escaped capture. Emerging at night he climbed and walked for eleven days to a trader's fort on the Little Big Horn.[14]

In 1810, Colter assisted in the construction of another fort located at Three Forks, Montana. After returning from gathering fur pelts, he discovered that two of his partners had been killed by the Blackfeet. This event convinced Colter to leave the wilderness for good and he returned to St. Louis before the end of 1810. He had been away from civilization for almost six years.[12]

The Colter Stone

Sometime between 1931 and 1933, an Idaho farmer named William Beard and his son discovered a rock carved into the shape of a man's head while clearing a field in Tetonia, Idaho, which is immediately west of the Teton Range. The rhyolite lava rock is 13 inches (330 mm) long, 8 inches (200 mm) wide and 4 inches (100 mm) thick and has the words "John Colter" carved on the right side of the face and the number "1808" on the left side and has been dubbed the "Colter Stone".[15] The stone was reportedly purchased from the Beards in 1933 by A.C. Lyon, who presented it to Grand Teton National Park in 1934. Fritiof Fryxell, noted mountain climber of numerous Teton Range peaks, geologist and Grand Teton National Park naturalist, concluded that the stone had weathering that indicated that the inscriptions were likely made in the year indicated.[15] Fryxell also believed that the Beards were not familiar with John Colter or his explorations. The stone has not been authenticated to have been carved by Colter, however, and may have instead been the work of later expeditions, possibly as a hoax, by members of the Hayden Survey in 1877.[15] If the stone is ever proven to be an actual carving made by Colter, in the year inscribed, it would coincide with the period he is known to have been in the region, and that he did cross the Teton Range and descend into Idaho, as descriptions he dictated to William Clark indicate.[16] Another possible artifact of Colter's was discovered within Yellowstone National Park in the 1880s. A log with the carved initials "J C" underneath a large X was discovered by Philip Ashton Rollins near Coulter Creek, an ironically named stream of no relation to Colter. Rollins and his party determined that the carving was roughly eighty years old. However, the authenticity of this artifact has never been identified as it was lost by Yellowstone employees around 1890 while being transferred to the Park museum.[2]

Final years and death

After returning to St. Louis, Colter married a woman named Sallie and purchased a farm near Miller's Landing, Missouri, now present-day New Haven, Missouri.[17] Somewhere around 1810, he visited with William Clark, his old commander from the Lewis and Clark Expedition, and provided detailed reports of his explorations since they had last met. From this information, Clark created a map which, despite its previously mentioned discrepancies, was the most comprehensive map produced of the region of the explorations for the next seventy-five years.[1] During the War of 1812, Colter enlisted and fought with Nathan Boone's Rangers.[17] Sources are unclear about when John Colter died or the exact cause of death. In one case, after suddenly turning ill, Colter is reported to have died of jaundice on May 7, 1812 and was buried near Miller's Landing, Missouri.[18][19] Other sources indicate he died on November 22, 1813.[9]

Legacy

Colter's legacy has had a profound impact on the image of the American West and frontier, with Colter's Run seeing many incarnations and recreations, including a retelling by the likes of Washington Irving. The stereotypes of reclusive frontier mountain men may be thanks to Nicholas Biddle's written characterizations of Colter, which paint him a man easily beguiled by the trapping prospects of the wilderness and intimidated by the possibility of returning to regular society.[2] Because no written materials attributed to Colter have ever been discovered (besides his signature,) Biddle's characterizations cannot be directly contested.

Traditionally, it is thought that Lewis and Clark's Expedition played a major role in heightening tensions between white explorers and the Blackfeet Indians. Despite this notion, Manuel Lisa's party originally interacted peacefully with the Blackfeet. However, it was after Colter and Potts were forced to battle the Blackfeet alongside the Flatheads and Crows that the relations between white explorers/trappers and the Blackfeet nation seemed to deteriorate. This led Major Biddle and many other frontiersman to draw the conclusion that Colter had actually upset relations with the Blackfeet, which was only expounded upon by the notoriety of Colter's Run.[2]

- A number of locations in northwestern Wyoming have been named after him, notably, Colter Bay on Jackson Lake in Grand Teton National Park and Colter Peak in the Absaroka Mountains in Yellowstone National Park.[20][21]

- A plaque commemorating Colter was displayed at a roadside pulloff on U.S. Route 340 just east of Stuarts Draft, near his birthplace. When the road was widened in 1998, the plaque was moved just north of the intersection of 340 and Route 608.

- A Kentucky Historical Marker commemorating John Colter as one of the Lewis and Clark Expedition's "nine young men from Kentucky" is located in Maysville, Kentucky at Limestone Landing, McDonald Parkway & Limestone St.

Popular culture

- The first motion picture, of John Colter's life, was the 1912 silent film, John Colter's Escape.

- The original script for director Cornel Wilde's 1965 movie, The Naked Prey, was largely based on Colter being pursued by Blackfoot Indians in Wyoming.[22]

- Roger Zelazny and Gerald Hausman meshed the stories of John Colter and Hugh Glass in the 1994 novel Wilderness.

- Colter's life and legend feature prominently in T. Coraghessan Boyle's 2015 novel The Harder They Come.

References

- ^ a b Zimmerman, Emily. "John Colter 1773?–1813". The Mountain Men: Pathfinders of the West 1810–1860. American Studies at the University of Virginia. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Harris, Burton (1993). John Colter, his years in the Rockies (1. Bison Book print. ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803272644.

- ^ Clark, Charles. "The Men of the Lewis and Clark Expedition". Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ "Private John Colter". PBS online. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted Courage. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 129. ISBN 0-684-82697-6.

- ^ a b c "Private John Colter". The Personnel of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted Courage. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 313–316. ISBN 0-684-82697-6.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted Courage. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 399. ISBN 0-684-82697-6.

- ^ a b c Morris, Larry E. (2004). The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10265-8.

- ^ a b "John Colter, the Phantom Explorer—1807–1808". Colter's Hell and Jackson Hole. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 14, 2006. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Page 30, James, Three Years Among the Indians and Mexicans

- ^ a b "Colter the Mountain Man". Discovering Lewis and Clark. Lewis-Clark.org. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Page 30, James, Three Years Among the Indians and Mexicans contains a somewhat different version of the struggle.

- ^ Pages 31–32, James, Three Years Among the Indians and Mexicans

- ^ a b c Daugherty, John (July 24, 2004). "The Fur Trappers". A Place Called Jackson Hole. Grand Teton Natural History Association. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ "The Mystery of the Colter Stone". History & Culture. Grand Teton National Park. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ a b "John Colter". The Lewis and Clark Rediscovery Project. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ "Burial Sites". The Lewis & Clark Journey of Discovery. National Park Service. Retrieved June 28, 2006.

- ^ "John Colter". Find A Grave. Retrieved June 29, 2006.

- ^ "Colter Bay, USGS Colter Bay (WY) Topo Map" (Map). TopoQuest USGS Quad. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

- ^ "Colter Peak, USGS Eagle Peak (WY) Topo Map" (Map). TopoQuest USGS Quads. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ^ "Trivia for The Naked Prey (1965)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

Further reading

- Anglin, Ronald M. and Larry E. Morris (2016). The Mystery of John Colter: The Man Who Discovered Yellowstone. Lanham, MD: Roman and Littlefield.

- James, Thomas (2008) [1916]. Three Years Among the Indians and Mexicans. ISBN 978-1-151-25120-6.

- LaLande, Jeff. "John Colter". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- Laut, Agnes C. (1921). "John Colter-Free Trapper". The Fur Trade in America (pdf). New York: MacMillan Company. pp. 236–252.