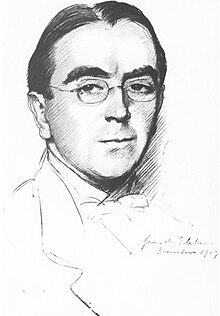

John Ireland (composer)

John Nicholson Ireland (13 August 1879 – 12 June 1962) was an English composer.

Life

John Ireland was born in Bowdon, near Altrincham, Cheshire, into a family of Scottish descent and some cultural distinction. His father, Alexander Ireland, a publisher and newspaper proprietor, was aged 70 at John's birth. John was the youngest of the five children from Alexander's second marriage (his first wife had died). His mother, Annie née Nicholson, was 30 years younger than Alexander. She died in October 1893, when John was 14, and Alexander died the following year, when John was 15.[1] John Ireland was described as "a self-critical, introspective man, haunted by memories of a sad childhood".[2]

Ireland entered the Royal College of Music in 1893, studying piano with Frederic Cliffe,[3] and organ, his second study, under Walter Parratt.[4] From 1897 he studied composition under Charles Villiers Stanford.[3] In 1896 Ireland was appointed sub-organist at Holy Trinity, Sloane Street, London SW1, and later, from 1904 until 1926, was organist and choirmaster at St Luke's Church, Chelsea.[5]

Ireland began to make his name in the early 1900s as a composer of songs and chamber music. His Violin Sonata No. 1 of 1909 won first prize in an international competition organised by the well-known patron of chamber music W. W. Cobbett. Even more successful was his Violin Sonata No. 2: completed in January 1917, he submitted this to a competition organised to assist musicians in wartime. The jury included the violinist Albert Sammons and the pianist William Murdoch, who both gave the work its first performance at Aeolian Hall in New Bond Street on 6 March that year. As Ireland recalled, "It was probably the first and only occasion when a British composer was lifted from relative obscurity in a single night by a work cast in a chamber-music medium." The work was enthusiastically reviewed, and the publisher Winthrop Rogers offered immediate publication (the first edition was sold out even before it had been processed by the printers). A subsequent performance of the Violin Sonata by Ireland and the violinist Désiré Defauw drew a packed audience to the Wigmore Hall in London.[6]

Ireland frequently visited the Channel Islands and was inspired by their landscape. In 1912 he composed the piano piece The Island Spell while staying on Jersey, and his Sarnia for piano was written there in 1940. He was evacuated from the islands just before the German invasion during World War II.

From 1923 he taught at the Royal College of Music.[7] His pupils there included Richard Arnell, Ernest John Moeran, Benjamin Britten (who later described Ireland as possessing "a strong personality but a weak character"),[8] the socialist composer Alan Bush,[7] Geoffrey Bush (no relation to Alan), who subsequently edited or arranged many of Ireland's works for publication, and Anthony Bernard.

John Ireland was a lifelong bachelor, except for a brief interlude when, in quick succession, he married, separated, and divorced. On 17 December 1926, aged 47, he married a 17-year pupil, Dorothy Phillips. This marriage was dissolved on 18 September 1928,[1] and it is believed not to have been consummated.[9] He took a similar interest in another young student, Helen Perkin (1909–1996), a pianist and composer, to whom he dedicated both the Piano Concerto in E flat and the Legend for piano and orchestra (which began life as a second concerto). She gave the premiere performance of both works,[1] but any thoughts he had for a deeper relationship with her came to nothing when she married George Mountford Adie, a disciple of George Gurdjieff, and she later moved with Adie to Australia.[10] Subsequently, Ireland withdrew the dedications. In 1947 Ireland acquired a personal assistant and companion, Mrs Norah Kirkby, who remained with him till his death.[1] Despite these associations with women, it is clear from his private papers that his interests lay elsewhere and many commentators support this view.[11]

On 10 September 1949, his 70th birthday was celebrated in a special Prom concert, at which his Piano Concerto was played by Eileen Joyce,[12] who was also the first pianist to record the concerto, in 1942.

Ireland retired in 1953, settling in the small hamlet of Rock in Sussex, where he lived in a converted windmill for the rest of his life. It was there he met the young pianist Alan Rowlands who would be Ireland's choice to record his complete piano music.[13]

He died of heart failure at age 82 in Washington, Sussex, and is buried at St. Mary the Virgin in Shipley, near his home. His epitaph reads "Many waters cannot quench love" and "One of God's noblest works lies here".

Music

From Stanford, Ireland inherited a thorough knowledge of the music of Beethoven, Brahms and other German classical composers, but as a young man he was also strongly influenced by Debussy and Ravel as well as by the earlier works of Stravinsky and Bartók. From these influences, he developed his own brand of "English Impressionism", related more closely to French and Russian models than to the folk-song style then prevailing in English music.

Like most other Impressionist composers, Ireland favoured small forms and wrote neither symphonies nor operas, although his Piano Concerto is among his best works. His output includes some chamber music and a substantial body of piano works, including his best-known piece The Holy Boy, known in numerous arrangements. His songs to poems by A. E. Housman, Thomas Hardy, Christina Rossetti, John Masefield, Rupert Brooke and others are a valuable addition to English vocal repertoire. Due to his job at St Luke's Church, he also wrote hymns, carols, and other sacred choral music; among choirs he is probably best known for the anthem Greater love hath no man, often sung in services that commemorate the victims of war. The hymn tune My Song Is Love Unknown is sung in churches throughout the English-speaking world, as is his Communion Service in C major.

He appears as pianist in a recording of his Fantasy-Sonata for Clarinet and Piano with Frederick Thurston,[14] and his Violin Sonata No. 1 (of 1909) with Frederick Grinke,[15] who performed and recorded several of his chamber works. His Piano Sonatina of 1926–27 and a number from his cycle Songs Sacred and Profane (1929) were dedicated to his friend the conductor and BBC music producer Edward Clark.[16][17][18]

Ireland wrote his only film score for the 1946 Australian film The Overlanders, from which an orchestral suite was extracted posthumously by Charles Mackerras. Some of his pieces, such as the popular A Downland Suite and Themes from Julius Caesar, were completed or re-transcribed after his death by his student Geoffrey Bush.

Works

Chamber works

- Fantasy-Sonata in E-flat/e-flat for clarinet and piano (1943)

- "The Holy Boy: A Carol of the Nativity" for cello and piano (arr. 1919)

- The Holy Boy: A Carol of the Nativity for string quartet

- Phantasie, Trio No. 1 in A minor for violin, cello and piano (1909)

- Sextet for clarinet, horn and string quartet (1898)

- Sonata in G minor for cello and piano (1923)

- Sonata No. 1 in D minor for violin and piano

- Sonata No. 2 in A minor for violin and piano (1915–1917)

- String Quartet No. 1 in D minor (1897)

- String Quartet No. 2 in C minor (1897)

- Trio No. 2 in One Movement for violin, cello and piano (1917)

- Trio No. 3 in E for violin, cello and piano (1938)

- Trio in D minor for clarinet, cello and piano (1912–1914)

Church music

- Benedictus in F

- Communion service in C

- Evening Service in F

- Greater love hath no man (motet)

- The Hills (chorus a capella)

- My Song Is Love Unknown (hymn)

- Te Deum in F

- Vexilla Regis (anthem)

- Ex Ore Innocentium (treble voices and organ or piano)

- Evening Service in A (SATB and organ)

- Evening Service in C (SATB and organ)

- Communion Service in A flat (Treble voices and organ)

Film score

- The Overlanders (1946)

Orchestra

- Comedy Overture (1937)

- Concertino Pastorale (string orchestra) (1939)

- A Downland Suite (1932)

- Epic March (1942)

- "The Holy Boy" (string orchestra) (1913)

- London Overture (1936)

- Mai-Dun (1920–21)

- Meditation on John Keble's Rogation Hymn (1958)

- Orchestral Poem

- Poem

- Satyricon – Overture (1946)

- Symphonic Rhapsody

- Symphonic Studies

- Two Symphonic Studies

Organ

- Alla marcia

- Capriccio

- Elegiac Romance

- Holy Boy

- Meditation on John Keble's Rogation Hymn

- Miniature Suite

- Sursum Corda

- Elegy (from Downlands Suite – arr. Alec Rowley)

- Epic March (arr. Robert Gower)

- Marcia Popolare

Piano

- The Almond Tree (1913)

- Ballad of London Nights (1930)

- Ballade (1931)

- Columbine (1949)

- The Darkened Valley (1920)

- Decorations (1912–13)

- The Island Spell

- Moonglade

- The Scarlet Ceremonies

- Equinox (1922)

- First Rhapsody in F sharp minor (1906)

- Green Ways – Three Lyric Pieces (1937)

- The Cherry Tree

- Cypress

- The Palm and May

- In Those Days (1895)

- Daydream

- Meridian

- Indian Summer (1932)

- Leaves from a Child's Sketchbook (1918)

- By the Mere

- In the Meadow

- The Hunt's Up

- London Pieces (1917–20)

- Chelsea Reach

- Ragamuffin

- Soho Forenoons

- Merry Andrew (1919)

- Month's Mind (1935)

- On a Birthday Morning (1922)

- Prelude in E flat (1924)

- Preludes (1913–5)

- The Undertone

- Obsession

- The Holy Boy

- Fire of Spring

- Rhapsody (1915)

- Sarnia: An Island Sequence (1940–1)

- Le Catioroc

- In a May morning

- Song of the Springtides

- A Sea Idyll (1920)

- Soliloquy (1922)

- Sonata in E (1920; premiered by Frederic Lamond on 12 June 1920, the only time he ever played it)[19]

- Sonatina (1926–7)

- Summer Evening (1920)

- The Towing Path (1918)

- Two Pieces (1921)

- For Remembrance

- Amberley Wild Brooks

- Two Pieces (1925)

- April

- Bergomask

- Two Pieces (1929–30)

- February's Child

- Aubade

- Three Dances (1913)

- Gypsy Dance

- Country Dance

- Reaper's Dance

- Three Pastels (1941)

- A Grecian Lad

- The Boy Bishop

- Puck's Birthday

Piano and orchestra

- Concerto in E-flat (1930)

- Legend (1933)

Songs

- Bells of San Marie

- During Music

- Friendship in Misfortune

- Hawthorn Time

- The Heart's Desire

- Her Song

- Holy Boy

- Horn the Hornblower

- I have twelve oxen

- If there were dreams to sell

- If we must part

- Land of Lost Content (song cycle)

- Love and Friendship

- Mother & Child (song cycle)

- My true love hath my heart

- Salley Gardens

- Santa Chiara

- Sea-Fever

- Song from o'er the hill

- Songs of the Wayfarer (song cycle)

- Songs Sacred and Profane (song cycle)

- Spring sorrow

- Spring Will Not Wait

- Thomas Hardy Songs

- Three Ravens

- The Trellis

- Tryst (in Fountain Court)

- The Vagabond

- What art thou thinking of?

- When I am dead, my dearest

Chorus and orchestra

- These Things Shall Be (1937)

Other (unclassified)

- Bagatelle

- Bed in Summer

- Berceuse

- Brooks Equinox

- Cavatina

- Elegiac Meditation

- The Forgotten Rite

- Scherzo & Cortege (1942)

- Tritons (1899)

References

- ^ a b c d Stewart R. Craggs, John Ireland. Ashgate Publishing (2007).

- ^ John Ireland: Biography from. Answers.com. Retrieved on 27 August 2011.

- ^ a b Hugh Ottaway. " Ireland, John (Nicholson)", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 6 June 2014 (subscription required)

- ^ Le Prevost, Stephen. "The Organ Music" in Foreman (2011): p. 4

- ^ Scott-Sutherland, Colin. "John Ireland: A Life in Music" in Foreman (2011): p. 4

- ^ Phillips, Bruce. "John Ireland's Chamber Music" in Foreman (2011): p. 227

- ^ a b Scott-Sutherland, Colin. "John Ireland: A Life in Music" in Foreman (2011): p. 5

- ^ Paul Kildea, Benjamin Britten: A Life in the Twentieth Century, p. 63

- ^ Hyperion: The Romantic Concerto 39. Hyperion-records.com. Retrieved on 27 August 2011.

- ^ Review of Lane’s recording. Amazon.com. Retrieved on 27 August 2011.

- ^ Hyperion, The Songs of John Ireland. Hyperion-records.co.uk. Retrieved on 27 August 2011.

- ^ Alan Bush Music Trust: The Correspondence of Alan Bush and John Ireland. Alanbushtrust.org.uk. Retrieved on 27 August 2011.

- ^ The John Ireland Companion. Boydell Pr. ISBN 1-84383-686-6.

- ^ CD: Symposium 1259, "probably recorded in 1948", http://www.arkivmusic.com/classical/Name/John-Ireland/Performer/5769-2.

- ^ ASIN: B00002MXU8

- ^ Lewis Foreman, The John Ireland Companion

- ^ IMSLP

- ^ Stewart R Craggs, John Ireland: A Catalogue, Discography and Bibliography

- ^ Lisa Hardy, The British Piano Sonata 1870–1945

Bibliography

- Foreman, Lewis (ed). The John Ireland Companion Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-84383-686-5

External links

- The John Ireland Trust

- John Ireland, from an original broadcast by Ian Lace

- Free scores by John Ireland in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- John Ireland discography

- Use dmy dates from April 2013

- 1879 births

- 1962 deaths

- 19th-century classical composers

- 20th-century classical composers

- Academics of the Royal College of Music

- Alumni of the Royal College of Music

- Classical composers of church music

- English classical composers

- English film score composers

- People educated at Leeds Grammar School

- English organists

- People from Altrincham

- Brass band composers

- Benjamin Britten