Karl Radek

Karl Radek | |

|---|---|

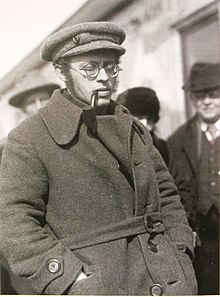

Karl Berngardovich Radek on the streets of Moscow | |

| Born | Karol Sobelsohn October 31, 1885 |

| Died | May 19, 1939 (aged 53) |

| Nationality | Austrian empire |

| Other names | Karl Berngardovich Radek |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire, Soviet Union |

| Occupation(s) | Revolutionary, writer, journalist, publicist, politician, theorist |

| Years active | - 1939 |

| Organization | Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Known for | Marxist revolutionary |

| Political party | Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL), Social Democratic Party of Germany(SPD), Communist Party of Germany (KPD), Comintern, Communist Workers' Party of Germany, Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

| Movement | Social democracy, communism, Bolshevik |

| Spouse(s) | Rosa Radek, Larisa Reisner |

| Children | Sofia Karlovna Radek |

Karl Berngardovich Radek (Russian: Карл Бернгардович Радек) (31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a Marxist active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and an international Communist leader in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution.

Early life

Radek was born in Lemberg, Austria-Hungary (now Lviv in Ukraine), as Karol Sobelsohn, to a Litvak family; his father, Bernhard, worked in the post office and died whilst Karl was young.[1] He took the name Radek from a favourite character, Andrzej Radek, in Syzyfowe prace ('The Labor of Sisyphus', 1897) by Stefan Żeromski.[2]

Radek joined the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) in 1904 and participated in the 1905 Revolution in Warsaw, where he had responsibility for the party's newspaper Czerwony Sztandar.[3]

Germany and "the Radek Affair"

In 1907, after his arrest in Poland and his escape from custody, Radek moved to Leipzig in Germany and joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), working on the Party's Leipziger Volkszeitung.[4] He re-located to Bremen, where he worked for Bremer Bürgerzeitung, in 1911, and was one of several who attacked Karl Kautsky's analysis of imperialism in Die Neue Zeit in May 1912.[5]

In September 1910, Radek was accused by members of the Polish Socialist Party of stealing books, clothes and money from party comrades, as part of an anti-semitic campaign against the SDKPiL. On this occasion, he was vigorously defended by the SDKPiL leaders, Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches. The following year, however, the SDKPiL changed course, partly because of a personality clash between Jogiches and Vladimir Lenin, during which younger members of the party, led by Yakov Hanecki, and including Radek, had sided with Lenin. Wanting to make an example of Radek, Jogiches revived the charges of theft, and convened a party commission in December 1911 to investigate. He dissolved the commission in July 1912, after it had failed to come to any conclusion, and in August pushed a decision through the party court expelling Radek. In their written finding, they broke his alias, making it - he claimed - dangerous for him to stay in Russian occupied Poland.[6]

In 1912 August Thalheimer invited Radek to go to Goppingen (near Stuttgart) to temporarily replace him in control of the local SPD party newspaper Freie Volkszeitung, which had financial difficulties. Radek accused the local party leadership in Württemberg of assisting the revisionists to strangle the newspaper due to the paper's hostility to them.[7] The 1913 SPD Congress noted Radek's expulsion and then went on to decide in principle that no-one who had been expelled from a sister-party could join another party within the Second International and retrospectively applied this rule to Radek.[7] Within the SPD Anton Pannekoek and Karl Liebknecht opposed this move, as did others in the International such as Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin,[7] some of whom participated in the "Paris Commission" set up by the International.[8]

World War I and the Russian Revolution

After the outbreak of World War I Radek moved to Switzerland where he worked as a liaison between Lenin and the Bremen Left, with which he had close links from his time in Germany, introducing him to Paul Levi at this time.[9] He took part in the Zimmerwald Conference in 1915, siding with the left.[10]

In 1917 Radek was one of the passengers on the sealed train that carried Lenin and other Russian revolutionaries through Germany after the February Revolution in Russia.[9] However, he was refused entry to Russia[10] and went on to Stockholm and produced the journals Russische Korrespondenz-Pravda and Bote der Russischen Revolution to publish Bolshevik documents and Russian information in German.[9]

After the October Revolution, Radek arrived in Petrograd and became Vice-Commissar for Foreign Affairs, taking part in the Brest-Litovsk treaty negotiations, as well as being responsible for the distribution of Bolshevik propaganda amongst German troops and prisoners of war.[11] During the discussions around signing the treaty, Radek was one of the advocates of a revolutionary war.[12]

Comintern and the German Revolution

After being refused recognition as official representative of the Bolshevik regime,[11] Radek and other delegates - Adolph Joffe, Nikolai Bukharin, Christian Rakovsky and Ignatov - traveled to the German Congress of Soviets.[13] After they were turned back at the border, Radek alone crossed the German border illegally in December 1918, arriving in Berlin on 19 or 20 December,[14] where he participated in the discussions and conferences leading to the foundation of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).[13] Radek was arrested after the Spartacist uprising on 12 February 1919 and held in Moabit prison until his release in January 1920.[13] While he was in Moabit, the attitude of the German authorities towards the Bolsheviks changed. The idea of creating an alliance of nations that had suffered from the Versailles treaty - principally Germany, Russia and Turkey - gained currency in Berlin, as a result of which Radek was allowed to receive a stream of visitors in his prison cell, including Walter Rathenau, Enver Pasha, and Ruth Fischer.[15][16]

On his return to Russia Radek became the Secretary of the Comintern, taking the main responsibility for German issues. He was removed from this position after he supported the KPD in opposing inviting representatives of the Communist Workers' Party of Germany to attend the 2nd Congress of the Comintern, pitting him against the Comintern's executive and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[17] It was Radek who took up the slogan of Stuttgart communists of fighting for a United Front with other working class organisations, that later formed the basis for the strategy developed by the Comintern.[18]

In mid-1923, Radek made his controversial speech 'Leo Schlageter: The Wanderer into the Void' at an open session of the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI).[19] In the speech he praised the actions of the German Freikorps officer and Nazi collaborator Leo Schlageter who had been shot whilst engaging in sabotage against French troops occupying the Ruhr area; in doing so Radek sought to explain the reasons why men like Schlageter were drawn towards the far right, and attempted to channel national grievances away from chauvinism and towards the support of the working movement and the Communists.[20]

Although Radek was not at Chemnitz when the decision to cancel the uprising in November 1923 took place at the KPD Zentrale, he subsequently approved the decision and defended it.[21] At subsequent congresses of the Russian Communist Party and meetings of the ECCI, Radek and Brandler were made the scapegoats for the defeat of the revolution by Zinoviev, with Radek being removed from the ECCI at the Fifth Congress of the Comintern.[22]

Into Opposition

Radek was part of the Left Opposition from 1923, writing his famed article 'Leon Trotsky: Organizer of Victory' shortly after Lenin's stroke in January of that year.[23] Later in the year at the Thirteenth Party Congress Radek was removed from the Central Committee.[24]

In the summer of 1925, Radek was appointed Provost of the newly established Sun Yat-Sen University[25] in Moscow, where Radek collected information for the opposition from students about the situation in China and cautiously began to challenge the official Comintern policy.[26] However, the terminal illness of Radek's lover, Larisa Reisner, saw Radek lose his inhibitions and he began publicly criticising Stalin, in particular debating Stalin's doctrine of Socialism in One Country at the Communist Academy.[27] Radek was sacked from his post at Sun Yat-Sen University in May 1927.[28]

Radek was expelled from the Party in 1927 after helping to organise an independent demonstration on the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution with Grigory Zinoviev in Leningrad.[29] In early 1928, when prominent oppositionists were deported to various remote locations within the Soviet Union, Radek was sent to Tobolsk[30] and a few months later moved on to Tomsk.[31]

Capitulation to Stalin and Show Trials

On 10 July 1929, Radek alongside other oppositionists Ivar Smilga and Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, signed a document capitulating to Stalin,[32] with Radek being held in particular disdain by oppositionist circles for his betrayal of Yakov Blumkin, who had been carrying a secret letter from Trotsky, in exile in Turkey, to Radek.[33] However, he was re-admitted in 1930 and was one of the few former oppositionists to retain a prominent place within the party, heading the International Information Bureau of the Russian Communist Party Central Committee[34] as well as giving the address on foreign literature at the First Soviet Writer's Conference in 1934.[35] In that speech, he denounced Marcel Proust and James Joyce, two of Europe's greatest 20th century novelists. He said that "in the pages of Proust, the old world, like a mangy dog no longer capable of any action whatever, lies basking in the sun and endlessly licks its sores" and compared Joyce's Ulysses to "a heap of dung, crawling with worms, photographed by a cinema apparatus through a microscope."[36] He helped to write the 1936 Soviet Constitution, but during the Great Purge of the 1930s, he was accused of treason and confessed, after two and a half months of interrogation,[33] at the Trial of the Seventeen (1937, also called the Second Moscow Trial). He was sentenced to 10 years of penal labor.

He was reportedly killed in a labor camp in a fight with another inmate. However, during an investigation in the Khrushchev Thaw it was established that he was killed by an NKVD operative under direct orders from Lavrentiy Beria.[37][38] Radek has also been credited with originating a number of political jokes about Joseph Stalin.[39] He was exonerated in 1988.[37]

Works

- March (1909)

- The Unity of the Working Class (1914)

- Marxism and the Problems of War (1916)

- The End of a Song (1918)

- The Development of Socialism from Science to Action (1918)

- Preface to Arthur Ransomes’s A Letter to America (1919)

- Karl Liebknecht – At the Martyr’s Graveside (1919)

- Anti-Parliamentarism (1920)

- Dictatorship and Terrorism (1920)

- The Labour Movement, Shop Committees and the Third International (1920)

- The Polish Question and the International (1920)

- England and the East (1920)

- Bertrand Russell’s Sentimental Journey (1921)

- Is the Russian Revolution a Bourgeois Revolution? (1921)

- The Downfall of Levi (1921)

- On the Trade Unions, at Second Congress of the Communist International Replying to the Discussion (1921)

- Outlines of World Politics (1922)

- The Paths of the Russian Revolution (1922)

- Foundation of the Two and a Half International (1922)

- Eve of Fusion of the Second and Two-and-a-Half International (1922)

- From the Hague to Essen (1922)

- The Greek Revolution (1922)

- The Winding-Up of the Versailles Treaty, Report to the IV. Congress of the Comintern (1923)

- Leon Trotsky, Organizer of Victory (1923)

- Ruhr and Hamburg (1923)

- Lenin (1923)

- The International Outlook (1923)

- Leo Schlageter: The Wanderer into the Void (“The Schlageter Speech”) (1923)

- Fascism and Communism (1924)

- Through Germany in the Sealed Coach (1926)

- November: A Page of Recollections (1926)

- A Letter to Klara Zetkin (1927)

- Larisa Reisner (1928)

- Appeal for Trotsky (1931)

- Capitalist Slavery vs. Socialist Organisation of Labour (1931)

- Greetings to Romain Rolland (1934)

- The Birth of the First International (1934)

- Fifteen Years of the Communist International (pamphlet) (1934)

- Contemporary World Literature and the Tasks of Proletarian Art (Speech at the Soviet Writers Congress) (1934)

- Felix Dzerzhinski (1935)

Notes

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.2

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.5

- ^ Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.635

- ^ Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.36

- ^ Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pp.36-7

- ^ Nettl, J.P. (1966). Rosa Luxemburg. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 584–586.

- ^ a b c Nettl, J.P. (1966) Rosa Luxemburg London: Oxford University Press, pgs.470-471

- ^ Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.891

- ^ a b c Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.87

- ^ a b Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.892

- ^ a b Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.893

- ^ Trotsky, L. (1970) My Life New York, Pathfinder, pg.453

- ^ a b c Carr, E. H. 'Introduction' In Radek, November (1926)

- ^ Nettl, J. P. (1969) Rosa Luxemburg: Abridged Edition Oxford: Oxford University Press pp.467

- ^ Radek, Karl (1962). "Karl Radek in Berlin". Archiv für Sozialgeschichte.

- ^ Fischer, Ruth (1948). Stalin and German Communism. A Study in the Origins of the State Party. Harvard University Press.

- ^ Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pp.893-4

- ^ Broue, P. (2007) 'Sparticism, Bolshevism and Ultra-Leftism in the Face of the Problems of the Proletarian Revolution in Germany (1918-1923)', Revolutionary History, Vol.9, No.4 pg.111

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.120

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.122

- ^ Broue, P. (2006) The German Revolution: 1917-1923, Chicago: Haymarket Books, pg.897

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.128-132

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press p. 127

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press p. 130

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.135

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.139-140

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press p. 140

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press p. 147

- ^ Trotsky, L. (1970) My Life New York, Pathfinder, p. 611

- ^ Broue, P. (2007) 'The Bolshevik-Leninist Faction' Revolutionary History Vol.9 No.4 p. 140

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press p. 150

- ^ Trotsky, L. (1981), The Challenge of the Left Opposition (1928-29) New York, Pathfinder, pg.157

- ^ a b Rogovin, R. Z. (1998) 1937: Stalin's Year of Terror Oak Park, Mehring Books pg.115

- ^ Rogovin, R. Z. (1998) 1937: Stalin's Year of Terror Oak Park, Mehring Books pg.114

- ^ Lerner, W. (1970) Karl Radek: The Last Internationalist Stanford: Stanford University Press pg.160

- ^ McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch. New York: The New Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-1-59558-056-6.

- ^ a b Template:Ru icon Karl Radek's biography article on hronos.ru

- ^ Template:Ru icon Document describing the murder of Radek and another political inmate, Sokolnikov

- ^ "In spite of his [Radek's] confession and reinstatement, he was bitterly critical of the government, and was credited with inventing most of the anti-government jokes then circulating in Moscow." Poretsky, Elisabeth (1969). Our Own People. University of Michigan Press. p. 185.

External links

- Works by Karl Radek available at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Biography on Spartacus Educational

- 1885 births

- 1939 deaths

- People from Lviv

- People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Jewish Ukrainian politicians

- Jews from Galicia (Eastern Europe)

- Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania politicians

- Old Bolsheviks

- Social Democratic Party of Germany politicians

- Communist Party of Germany politicians

- Comintern people

- Executive Committee of the Communist International

- Jewish socialists

- Gulag detainees

- Great Purge victims from Ukraine

- Jewish people executed by the Soviet Union

- National Bolshevism

- Trial of the Seventeen

- Soviet Jews

- Treaty of Brest-Litovsk