Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell is an iconic symbol of American Independence, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Formerly located in the steeple of the Pennsylvania State House (now renamed Independence Hall), the bell was commissioned from the London firm of Lester and Pack (today the Whitechapel Bell Foundry) in 1752, and was cast with the lettering (part of Leviticus 25:10) "Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof." It originally cracked when first rung after arrival in Philadelphia, and was twice recast by local workmen John Pass and John Stow, whose last names appear on the bell. In its early years, the Liberty Bell was used to summon lawmakers to legislative sessions and to alert citizens to public meetings and proclamations.

Bells were rung to mark the reading of the Declaration on July 8, 1776, and while there is no contemporary account of the Liberty Bell ringing, most historians believe it was one of the bells rung. After American independence was secured, it fell into relative obscurity for some years. In the 1830s, the bell was adopted as a symbol by abolitionist societies, who dubbed it the "Liberty Bell". It acquired its distinctive large crack sometime in the early 19th century—a widespread story claims it cracked while ringing after the death of Chief Justice John Marshall in 1835.

The bell became widely famous after an 1847 short story claimed that an aged bell-ringer rang it on July 4, 1776, upon hearing of the Second Continental Congress's vote for independence. While the bell could not have been rung on that Fourth of July, as no announcement of the Declaration was made that day, the tale was widely accepted as fact, even by some historians. Beginning in 1885, the City of Philadelphia, which owns the bell, allowed it to go to various expositions and patriotic gatherings. The bell attracted huge crowds wherever it went, additional cracking occurred and pieces were chipped away by souvenir hunters. The last such journey occurred in 1915, after which the city refused further requests.

After World War II, the city allowed the National Park Service to take custody of the bell, while retaining ownership. The bell was used as a symbol of freedom during the Cold War and was a popular site for protests in the 1960s. It was moved from its longtime home in Independence Hall to a nearby glass pavilion on Independence Mall in 1976, and then to the larger Liberty Bell Center adjacent to the pavilion in 2003. The bell has been featured on coins and stamps, and its name and image have been widely used by corporations.

Founding (1751–1753)

Philadelphia's city bell had been used to alert the public to proclamations or civic danger since the city's 1682 founding. The original bell hung from a tree behind the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) and was said to have been brought to the city by its founder, William Penn. In 1751, with a bell tower being built in the Pennsylvania State House, civic authorities sought a bell of better quality, which could be heard at a further distance in the rapidly expanding city.[1] Isaac Norris, speaker of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly, gave orders to the colony's London agent, Robert Charles, to obtain a "good Bell of about two thousands pound weight".[2]

We hope and rely on thy care and assistance in this affair and that thou wilt procure and forward it by the first good oppo as our workmen inform us it will be much less trouble to hang the Bell before their Scaffolds are struck from the Building where we intend to place it which will not be done 'till the end of next Summer or beginning of the Fall. Let the bell be cast by the best workmen & examined carefully before it is Shipped with the following words well shaped around it vizt.

By Order of the Assembly of the Povince [sic] of Pensylvania [sic] for the State house in the City of Philada 1752

and Underneath

Proclaim Liberty thro' all the Land to all the Inhabitants thereof.-Levit. XXV. 10.[2]

Charles duly ordered the bell from Thomas Lester of the London bellfounding firm of Lester and Pack (today the Whitechapel Bell Foundry)[3] for the sum of £150 13s 8d,[4] (equivalent to approximately $36,400 today)[5] including freight to Philadelphia and insurance. It arrived in Philadelphia in August 1752. Norris wrote to Charles that the bell was in good order, but they had not yet sounded it, as they were building a clock for the State House's tower.[6] The bell was mounted on a stand to test the sound, and at the first strike of the clapper, the bell's rim cracked. The episode would be used to good account in later stories of the bell;[7] in 1893, former President Benjamin Harrison, speaking as the bell passed through Indianapolis, stated, "This old bell was made in England, but it had to be re-cast in America before it was attuned to proclaim the right of self-government and the equal rights of men."[8] Philadelphia authorities tried to return it by ship, but the master of the vessel which had brought it was unable to take it on board.[9]

Two local founders, John Pass and John Stow, offered to recast the bell. Though they were inexperienced in bell casting, Pass had headed the Mount Holly Iron Foundry in neighboring New Jersey and came from Malta, which had a tradition of bell casting. Stow, on the other hand, was only four years out of his apprenticeship as a brass founder. At Stow's foundry on Second Street, the bell was broken into small pieces, melted down, and cast into a new bell. The two founders decided that the metal was too brittle, and augmented the bell metal by about ten percent, using copper. The bell was ready in March 1753, and Norris reported that the lettering (which included the founders' names and the year) was even clearer on the new bell than on the old.[10]

City officials scheduled a public celebration with free food and drink for the testing of the recast bell. When the bell was struck, it did not break, but the sound produced was described by one hearer as like two coal scuttles being banged together. Mocked by the crowd, Pass and Stow hastily took the bell away and again recast it. When the fruit of the two founders' renewed efforts was brought forth in June 1753, the sound was deemed satisfactory, though Norris indicated that he did not personally like it. The bell was hung in the steeple of the State House the same month.[11]

The reason for the difficulties with the bell is not certain. The Whitechapel Foundry, still in business today, takes the position that the bell was either damaged in transit or was broken by an inexperienced bell ringer, who incautiously sent the clapper flying against the rim, rather than the body of the bell.[12] In 1975, the Winterthur Museum conducted an analysis of the metal in the bell, and concluded that "a series of errors made in the construction, reconstruction, and second reconstruction of the Bell resulted in a brittle bell that barely missed being broken up for scrap".[13] The Museum found a considerably higher level of tin in the Liberty Bell than in other Whitechapel bells of that era, and suggested that Whitechapel made an error in the alloy, perhaps by using scraps with a high level of tin to begin the melt instead of the usual pure copper.[14] The analysis found that, on the second recasting, instead of adding pure tin to the bell metal, Pass and Stow added cheap pewter with a high lead content, and incompletely mixed the new metal into the mold.[15] The result was "an extremely brittle alloy which not only caused the Bell to fail in service but made it easy for early souvenir collectors to knock off substantial trophies from the rim".[16]

Early days (1754–1846)

Dissatisfied with the bell, Norris instructed Charles to order a second one, and see if Lester and Pack would take back the first bell and credit the value of the metal towards the bill. In 1754, the Assembly decided to keep both bells; the new one was attached to the tower clock[17] while the old bell was, by vote of the Assembly, devoted "to such Uses as this House may hereafter appoint."[17] The Pass and Stow bell was used to summon the Assembly.[18] One of the earliest documented mentions of the bell's use is in a letter from Benjamin Franklin to Catherine Ray dated October 16, 1755: "Adieu. The Bell rings, and I must go among the Grave ones, and talk Politiks. [sic]"[19] The bell was rung in 1760 to mark the accession of George III to the throne.[18] In the early 1760s, the Assembly allowed a local church to use the State House for services and the bell to summon worshipers, while the church's building was being constructed.[19] The bell was also used to summon people to public meetings, and in 1772, a group of citizens complained to the Assembly that the bell was being rung too frequently.[18]

Despite the legends that have grown up about the Liberty Bell, it did not ring on July 4, 1776, as no public announcement was made of the Declaration of Independence. When the Declaration was publicly read on July 8, 1776, there was a ringing of bells, and while there is no contemporary account of this particular bell ringing, most authorities agree that the Liberty Bell was among the bells that rang.[20][21] However, there is some chance that the poor condition of the State House bell tower prevented the bell from ringing.[21] According to John C. Paige, who wrote a historical study of the bell for the National Park Service, "We do not know whether or not the steeple was still strong enough to permit the State House bell to ring on this day. If it could possibly be rung, we can assume it was. Whether or not it did, it has come to symbolize all of the bells throughout the United States which proclaimed Independence."[22]

If the bell was rung, it would have been most likely rung by Andrew McNair, who was the doorkeeper both of the Assembly and of the Congress, and was responsible for ringing the bell. As McNair was absent on two unspecified days between April and November, it might have been rung by William Hurry, who succeeded him as doorkeeper for Congress.[23] Bells were also rung to celebrate the first anniversary of Independence on July 4, 1777.[21]

After Washington's defeat at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia was defenseless, and the city prepared for what was seen as an inevitable British attack. Bells could easily be recast into munitions, and locals feared the Liberty Bell and other bells would meet this fate. The bell was hastily taken down from the tower, and sent by heavily guarded wagon train to the town of Bethlehem. Local wagoneers transported the bell to the Zion German Reformed Church in Allentown, where it waited out the British occupation of Philadelphia behind a false wall.[24] It was returned to Philadelphia in June 1778, after the British departure. With the steeple of the State House in poor condition (the steeple was subsequently torn down and later restored), the bell was placed in storage, and it was not until 1785 that it was again mounted for ringing.[25]

Mounted on an upper floor of the State House, the bell was rung in the early years of independence on the Fourth of July and on Washington's Birthday, as well as on Election Day to remind voters to hand in their ballots. It also rang to call students at the University of Pennsylvania to their classes at nearby Philosophical Hall. Until 1799, when the state capital was moved to Lancaster, it again rang to summon legislators into session.[26] When the State of Pennsylvania, having no further use for its State House, proposed to tear it down and sell the land for building lots, the City of Philadelphia purchased the land, together with the building, including the bell, for $70,000.[27] In 1828, the city sold the second Lester and Pack bell to St. Augustine's Roman Catholic Church, which was burned down by an anti-Catholic mob in the Philadelphia Nativist Riots of 1844. The remains of the bell were recast into a new bell, which is found at Villanova University.[28]

It is uncertain how the bell came to be cracked; the damage occurred sometime between 1817 and 1846. The bell is mentioned in a number of newspaper articles during that time; no mention of a crack can be found until 1846. In fact, in 1837, the bell was depicted in an anti-slavery publication—uncracked. In February 1846 Public Ledger reported that the bell had been rung on February 23, 1846 in celebration of Washington's Birthday (as February 22 fell on a Sunday, the celebration occurred the next day), and also reported that the bell had long been cracked, but had been "put in order" by having the sides of the crack filed. The paper reported that around noon, it was discovered that the ringing had caused the crack to be greatly extended, and that "the old Independence Bell...now hangs in the great city steeple irreparably cracked and forever dumb".[29]

The most common story about the cracking of the bell is that it happened when the bell was rung upon the 1835 death of the Chief Justice of the United States, John Marshall. This story originated in 1876, when the volunteer curator of Independence Hall, Colonel Frank Etting, announced that he had ascertained the truth of the story. While there is little evidence to support this view, it has been widely accepted and taught. Other claims regarding the crack in the bell include stories that it was damaged while welcoming Lafayette on his return to the United States in 1824, that it cracked announcing the passing of the British Catholic Relief Act 1829, and that some boys had been invited to ring the bell, and inadvertently damaged it. David Kimball, in his book compiled for the National Park Service, suggests that it most likely cracked sometime between 1841 and 1845, either on the Fourth of July or on Washington's Birthday.[30]

The Pass and Stow bell was first termed "the Liberty Bell" in the New York Anti-Slavery Society's journal, Anti-Slavery Record. In an 1835 piece, "The Liberty Bell", Philadelphians were castigated for not doing more for the abolitionist cause. Two years later, another work of that society, the journal Liberty featured an image of the bell as its frontispiece, with the words "Proclaim Liberty".[31] In 1839, Boston's Friends of Liberty, another abolitionist group, titled their journal The Liberty Bell. The same year, William Lloyd Garrison's anti-slavery publication The Liberator reprinted a Boston abolitionist pamphlet containing a poem entitled, "The Liberty Bell," which noted that, at that time, despite its inscription, the bell did not proclaim liberty to all the inhabitants of the land.[32]

Becoming a symbol (1847–1865)

A great part of the modern image of the bell as a relic of the proclamation of American independence was forged by writer George Lippard. On January 2, 1847, his story "Fourth of July, 1776" appeared in Saturday Review magazine. The short story depicted an aged bellman on July 4, 1776, sitting morosely by the bell, fearing that Congress would not have the courage to declare independence. At the most dramatic moment, a young boy appears with instructions for the old man: to ring the bell. The story was widely reprinted and closely linked the Liberty Bell to the Declaration of Independence in the public mind.[33] The elements of the story were reprinted in early historian Benson J. Lossing's The Pictorial Field Guide to the Revolution (published in 1850) as historical fact,[34] and the tale was widely repeated for generations to come in school primers.[35]

In 1848, with the rise of interest in the bell, the city decided to move it to the Assembly Room (also known as the Declaration Chamber) on the first floor, where the Declaration and United States Constitution had been debated and signed.[36] The city constructed an ornate pedestal for the bell. The Liberty Bell was displayed on that pedestal for the next quarter-century, surmounted by an eagle (originally sculpted, later stuffed).[37] In 1853, President Franklin Pierce visited Philadelphia and the bell, and spoke of the bell as symbolizing the American Revolution and American liberty.[38] At the time, Independence Hall was also used as a courthouse, and African-American newspapers pointed out the incongruity of housing a symbol of liberty in the same building in which federal judges were holding hearings under the Fugitive Slave Act.[39]

In February 1861, the President-elect, Abraham Lincoln, came to the Assembly Room and delivered an address en route to his inauguration in Washington DC.[40] In 1865, Lincoln's body was returned to the Assembly Room after his assassination for a public viewing of his body, en route to his burial in Springfield, Illinois. Due to time constraints, only a small fraction of those wishing to pass by the coffin were able to; the lines to see the coffin were never less than 3 miles (4.8 km) long.[41] Nevertheless, between 120,000 and 140,000 people were able to pass by the open casket and then the bell, carefully placed at Lincoln's head so mourners could read the inscription, "Proclaim Liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof."[40]

Traveling icon of freedom (1866–1947)

In 1876, city officials discussed what role the bell should play in the nation's Centennial festivities. Some wanted to repair it so it could sound at the Centennial Exposition being held in Philadelphia, but the idea was not adopted; the bell's custodians concluded that it was unlikely that the metal could be made into a bell which would have a pleasant sound, and that the crack had become part of the bell's character. Instead, a replica weighing 13,000 pounds (5,900 kg) (1,000 pounds for each of the original states) was cast. The metal used for what was dubbed "the Centennial Bell" included four melted-down cannons: one used by each side in the American Revolutionary War, and one used by each side in the Civil War. That bell was sounded at the Exposition grounds on July 4, 1876, was later recast to improve the sound, and today is the bell attached to the clock in the steeple of Independence Hall.[42] While the Liberty Bell did not go to the Exposition, a great many Exposition visitors came to visit it, and its image was ubiquitous at the Exposition grounds—myriad souvenirs were sold bearing its image or shape, and state pavilions contained replicas of the bell made of substances ranging from stone to tobacco.[43] In 1877, the bell was hung from the ceiling of the Assembly Room by a chain with thirteen links.[44]

Between 1885 and 1915, the Liberty Bell made seven trips to various expositions and celebrations. Each time, the bell traveled by rail, making a large number of stops along the way so that local people could view it.[45] By 1885, the Liberty Bell was internationally recognized as a symbol of freedom, and as a treasured relic of independence, and was growing still more famous as versions of Lippard's legend were reprinted in history and school books.[46] In early 1885, the city agreed to let it travel to New Orleans for the World Cotton Centennial exposition. Large crowds mobbed the bell at each stop. In Biloxi, Mississippi, the former President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis came to the bell. Davis delivered a speech paying homage to it, and urging national unity.[47] In 1893, it was sent to Chicago's World Columbian Exposition to be the centerpiece of the state's exhibit in the Pennsylvania Building.[48] On July 4, 1893, in Chicago, the bell was honored with the first performance of The Liberty Bell March, conducted by "America's Bandleader", John Phillip Sousa.[49] Philadelphians began to cool to the idea of sending it to other cities when it returned from Chicago bearing a new crack, and each new proposed journey met with increasing opposition.[50] It was also found that the bell's private watchman had been cutting off small pieces for souvenirs. The city placed the bell in a glass-fronted oak case in the Assembly Room.[51] In 1898, it was taken out of the glass case and hung from its yoke again in the tower hall of Independence Hall, a room which would remain its home until the end of 1975. A guard was posted to discourage souvenir hunters who might otherwise chip at it.[52]

By 1909, the bell had made six trips, and not only had the cracking become worse, but souvenir hunters had deprived it of over one percent of its weight. When, in 1912, the organizers of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition requested the bell for the 1915 fair in San Francisco, the city was reluctant to let it travel again. The city finally decided to let it go as the bell had never been west of St. Louis, and it was a chance to bring it to millions who might never see it otherwise.[53] However, in 1914, fearing that the cracks might lengthen during the long train ride, the city installed a metal support structure inside the bell, generally called the "spider."[54] In February 1915, the bell was tapped gently with wooden mallets to produce sounds which were transmitted to the fair as the signal to open it, a transmission which also inaugurated transcontinental telephone service.[55] Some five million Americans saw the bell on its train journey west.[56] It is estimated that nearly two million kissed it at the fair, with an uncounted number viewing it. The bell was taken on a different route on its way home; again, five million saw it on the return journey.[57] Since the bell returned to Philadelphia, it has been moved out of doors only five times: three times for patriotic observances during and after World War I, and twice as the bell occupied new homes in 1976 and 2003.[50][58] Chicago and San Francisco had obtained its presence after presenting petitions signed by hundreds of thousands of children. Chicago tried again, with a petition signed by 3.4 million schoolchildren, for the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition and New York presented a petition to secure a visit from the bell for the 1939 New York World's Fair. Both efforts failed.[59]

In 1924, one of Independence Hall's exterior doors was replaced by glass, allowing some view of the bell even when the building was closed.[60] When Congress enacted the nation's first peacetime draft in 1940, the first Philadelphians required to serve took their oaths of enlistment before the Liberty Bell. Once the war started, the bell was again a symbol, used to sell war bonds.[61] In the early days of World War II, it was feared that the bell might be in danger from saboteurs or enemy bombing, and city officials considered moving the bell to Fort Knox, to be stored with the nation's gold reserves. The idea provoked a storm of protest from around the nation, and was abandoned. Officials then considered building an underground steel vault above which it would be displayed, and into which it could be lowered if necessary. The project was dropped when studies found that the digging might undermine the foundations of Independence Hall.[62] The bell was again tapped on D-Day, as well as in victory on V-E Day and V-J Day.[63]

Park Service administration (1948–present)

After World War II, and following considerable controversy, the City of Philadelphia agreed that it would transfer custody of the bell and Independence Hall, while retaining ownership, to the federal government. The city would also transfer various colonial-era buildings it owned. Congress agreed to the transfer in 1948, and three years later Independence National Historical Park was founded, incorporating those properties and administered by the National Park Service (NPS or Park Service).[64] The Park Service would be responsible for maintaining and displaying the bell.[65]The NPS would also administer the three blocks just north of Independence Hall, which had been condemned by the state, razed, and developed into a park, Independence Mall.[64]

In the postwar period, the bell became a symbol of freedom used in the Cold War. The bell was chosen for the symbol of a savings bond campaign in 1950. The purpose of this campaign, as Vice President Alben Barkley put it, was to make the country "so strong that no one can impose ruthless, godless ideologies on us".[65] In 1955, former residents of nations behind the Iron Curtain were allowed to tap the bell as a symbol of hope and encouragement to their compatriots.[66] Foreign dignitaries, such as Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion and West Berlin Mayor Ernst Reuter were brought to the bell, and they commented that the bell symbolized the link between the United States and their nations.[65] During the 1960s, the bell was the site of several protests, both for the civil rights movement, and by various protesters supporting or opposing the Vietnam War.[67]

Almost from the start of its stewardship, the Park Service sought to move the bell from Independence Hall to a structure where it would be easier to care for the bell and accommodate visitors. The first such proposal was withdrawn in 1958, after considerable public protest.[68] The Park Service tried again as part of the planning for the United States Bicentennial. The Independence National Historical Park Advisory Committee proposed in 1969 that the bell be moved out of Independence Hall, as the building could not accommodate the millions expected to visit Philadelphia for the Bicentennial.[69] In 1972, the Park Service announced plans to build a large glass tower for the bell at the new visitor's center at South Third Street and Chestnut Street, two blocks east of Independence Hall, at a cost of $5 million, but citizens again protested the move. Instead, in 1973, the Park Service proposed to build a smaller glass pavilion for the bell at the north end of Independence Mall, between Arch and Race Streets. Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo agreed with the pavilion idea, but proposed that the pavilion be built across Chestnut Street from Independence Hall, which the state feared would destroy the view of the historic building from the mall area.[70] Rizzo's view prevailed, and the bell was moved to a glass and steel pavilion, about 100 yards (91 m) from its old home at Independence Hall as the Bicentennial year began.[71]

During the Bicentennial, members of the Procrastinator's Club of America jokingly picketed the Whitechapel Bell Foundry with signs "We got a lemon" and "What about the warranty?" The foundry told the protesters that it would be glad to replace the bell—so long as it was returned in the original packaging.[9] In 1958, the foundry (then trading under the name Mears and Stainbank Foundry) had offered to recast the bell, and and was told by the Park Service that neither it nor the public wanted the crack removed.[68] The foundry was called upon, in 1976, to cast a full-size replica of the Liberty Bell, which was presented to the United States by the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II,[72] and which is now housed in the tower once intended for the Liberty Bell, by the former visitors center on South Third Street.[73]

In 2001, the Park Service began work on a new home for the Liberty Bell, on the same block as the pavilion, but significantly larger, allowing for exhibit space and an interpretative center. Archaeologists discovered evidence that the construction site included an area that was once the location of a structure used by George Washington, while living in Philadelphia as president, to house his slaves. The Park Service was reluctant to include exhibits commemorating the slaves at the new Liberty Bell Center, but after protests by Black activists, agreed. The new facility, which opened after the bell was installed on October 9, 2003, is adjacent to an outline of the slaves' house marked in the pavement, with interpretive signs explaining the significance of what was found. Inside, visitors pass through a number of exhibits about the bell before reaching the Liberty Bell itself. Due to security concerns following an attack on the bell by a visitor with a hammer in 2001, the bell is hung out of easy reach of visitors, who are no longer allowed to touch it, and all visitors undergo a security screening.[74]

Today, the Liberty Bell weighs 2,080 pounds (940 kg). Its metal is 70% copper and 25% tin, with the remainder consisting of lead, zinc, arsenic, gold and silver. It hangs from what is believed to be its original yoke, made from American elm.[75] While the crack in the bell appears to end at the abbreviation "Philada" in the last line of the inscription, that is merely the 19th century widened crack which was filed out in the hopes of allowing the bell to continue to ring; a hairline crack, extending through the bell to the inside continues generally right and gradually moving to the top of the bell, through the word "and" in "Pass and Stow", then through the word "the" before the word "Assembly" in the second line of text, and through the letters "rty" in the word "Liberty" in the first line. The crack ends near the attachment with the yoke.[76]

Professor Constance M. Greiff, in her book tracing the history of Independence National Historical Park, wrote of the Liberty Bell:

[T]he Liberty Bell is the most venerated object in the park, a national icon. It is not as beautiful as some other things that were in Independence Hall in those momentous days two hundred years ago, and it is irreparably damaged. Perhaps that is part of its almost mystical appeal. Like our democracy it is fragile and imperfect, but it has weathered threats, and it has endured.[77]

Replicas and popular culture

In addition to the replicas which are seen at Independence National Historical Park, early replicas of the Liberty Bell include the so-called Justice Bell or Women's Liberty Bell, commissioned in 1915 by suffragists to advocate for women's suffrage. This bell had the same legend as the Liberty Bell, with two added words, "establish justice", words taken from the Preamble to the United States Constitution. It also had the clapper chained to the bell so it could not sound, symbolizing the inability of women, lacking the vote, to influence political events. The Justice Bell toured extensively to publicize the cause. After the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment (granting women the vote), the Justice Bell was brought to the front of Independence Hall on August 26, 1920 to finally sound. It remained on a platform before Independence Hall for several months before city officials required that it be taken away, and today is at the Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge.[78]

As part of the Liberty Bell Savings Bonds drive in 1950, 55 replicas of the Liberty Bell (one each for the 48 states, the District of Columbia, and the territories) were ordered by the United States Department of the Treasury and were cast in France. The bells were to be displayed and rung on patriotic occasions.[79] Many of the bells today are sited near state capitol buildings.[79] Although Wisconsin's bell is now at its state capitol, initially it was sited on the grounds of the state's Girls Detention Center. Texas's bell is at Texas A & M University in College Station.[79] The Texas bell was presented to the university in appreciation of the service of the school's graduates.[79]

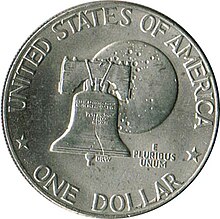

The Liberty Bell appeared on a commemorative coin in 1926 to mark the sesquicentennial of American independence.[80] Its first use on a circulating coin was on the reverse side of the Franklin half dollar, struck between 1948 and 1963.[81] It also appeared on the Bicentennial design of the Eisenhower dollar, superimposed against the moon.[82] The first U.S. stamp showing a depiction of the Liberty Bell was issued for the Sesquicentennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1926,[83] though this stamp actually depicts the replica bell erected at the entrance to the exposition grounds.[84] The bell appears on the forever stamp issued since 2007, which increases in face value as postal rates rise.[85]

The name "Liberty Bell" or "Liberty Belle" is commonly used for commercial purposes, and has denoted brands and business names ranging from a life insurance company to a Montana escort service.[86] A large outline of the bell hangs over the right-field bleachers at Citizens Bank Park, home of the Philadelphia Phillies baseball team, and is illuminated whenever one of their players hits a home run.[87] This bell outline replaced one at the Phillies' former home, Veterans Stadium.[88] On April 1, 1996, Taco Bell announced via ads and press releases that it had purchased the Liberty Bell and changed its name to the Taco Liberty Bell. The bell, the ads related, would henceforth spend half the year at Taco Bell corporate headquarters in Irvine, California. Outraged calls flooded Independence National Historical Park, and Park Service officials hastily called a press conference to deny that the bell had been sold. After several hours, Taco Bell admitted that it was an April Fools Day joke. Despite the protests, company sales of tacos, enchiladas, and burritos rose by more than a half million dollars that week.[89]

Inscription

The bell's inscription is given below:

PROCLAIM LIBERTY THROUGHOUT ALL THE LAND UNTO ALL THE INHABITANTS THEREOF LEV. XXV. V X.

BY ORDER OF THE ASSEMBLY OF THE PROVINCE OF PENSYLVANIA FOR THE STATE HOUSE IN PHILADA

PHILADA

At the time, "Pensylvania" was an accepted alternative spelling for "Pennsylvania." That spelling was used by Alexander Hamilton, a graduate of Columbia University, in 1787 on the signature page of the United States Constitution.[90]

See also

- The Mercury spacecraft that astronaut Gus Grissom flew on July 21, 1961, was dubbed Liberty Bell 7. Mercury capsules were somewhat bell-shaped, and this one received a painted crack to mimic the original bell.

- Margaret Buechner composed a work for chorus and orchestra, "Liberty Bell", that incorporates a 1959 recording of the actual bell made by Columbia Records.

- The superhero Liberty Belle whose powers are derived from the ringing of the bell.

References

Notes

- ^ Nash, pp. 1–2

- ^ a b Paige, pp. 2–3

- ^ The Franklin Institute, p. 19

- ^ One hundred fifty pounds, thirteen shillings and eightpence.

- ^ Purchasing power of British Pounds from 1264 to present. measuringworth.com. Retrieved 2010–08–26.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) The same site indicates that the pound sterling was worth $1.85 in 2008. - ^ Kimball, p. 20

- ^ Nash, p. 7

- ^ Pierce, James Wilson (1893). Photographic History of the World's fair and Sketch of the City of Chicago. Baltimore: R. H. Woodward & Co. p. 491. Retrieved 2010–08–17.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b "The Liberty Bell". Whitechapel Bell Foundry. Retrieved 2010–08–09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nash, p. 7–10

- ^ Nash, pp. 10–11

- ^ Nash, p. 9

- ^ Hanson, p. 7

- ^ Hanson, p. 5

- ^ Hanson, p. 4

- ^ Hanson, p. 3

- ^ a b Nash, pp. 11–12

- ^ a b c Kimball, pp. 31–32

- ^ a b Paige, p. 13

- ^ Kimball, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b c Nash, pp. 17–18

- ^ Paige, p. 18

- ^ Paige, pp. 17–18

- ^ Nash, p. 19

- ^ Kimball, p. 37

- ^ Kimball, pp. 37–38

- ^ Kimball, p. 38

- ^ Kimball, p. 70

- ^ Kimball, pp. 43–45

- ^ Kimball, pp. 43–47

- ^ Nash, p. 36

- ^ Nash, pp. 37–38

- ^ Kimball, p. 56

- ^ Paige, p. 83

- ^ de Bolla, p. 108

- ^ Nash, p. 47

- ^ Nash, pp. 50–51

- ^ Kimball, p. 60

- ^ Nash, pp. 48–49

- ^ a b Hoch, Bradley R. (Summer 2004). "The Lincoln landscape: Looking for Lincoln's Philadelphia: A personal journey from Washington Square to Independence Hall". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 25 (2): 59–70. Retrieved 2010–08–10.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Schwartz, Barry (2003). Abraham Lincoln and the Forge of National Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 40. ISBN 0226741982. Retrieved 2010–08–10.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nash, pp. 63–65

- ^ Nash, pp. 66–68

- ^ Kimball, p. 68

- ^ de Bolla, p. 111

- ^ Nash, p. 77

- ^ Nash, pp. 79–80

- ^ Nash, pp. 84–85

- ^ Nash, pp. 89–90

- ^ a b Kimball, p. 69

- ^ Nash, p. 98

- ^ Paige, p. 43

- ^ Nash, pp. 110–112

- ^ The Franklin Institute, pp. 28–29

- ^ Nash, p. 113

- ^ Nash, p. 123

- ^ Nash, pp. 113–115

- ^ Paige, p. 54

- ^ Nash, p. 140

- ^ Paige, p. 57

- ^ Nash, pp. 148–151

- ^ Paige, pp. 64–65

- ^ Kimball, p. 71

- ^ a b Nash, pp. 172–173

- ^ a b c Paige, p. 69

- ^ Paige, p. 71

- ^ Paige, pp. 76–78

- ^ a b Paige, p. 72

- ^ Paige, p. 78

- ^ "New home sought for Liberty Bell". The New York Times. New York. 1973–09–04. p. 15. Retrieved 2010–08–10 (subscription required).

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Wooten, James T. (1976–01–01). "Move of Liberty Bell opens Bicentennial". The New York Times. New York. p. 1. Retrieved 2010–08–10 (subscription required).

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Nash, pp. 177–178

- ^ Greiff, pp. 214–215

- ^ Yamin, Rebecca (2008). Digging in the City of Brotherly Love: Stories from Philadelphia Archeology. New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press. pp. 39–53. ISBN 0300100914. Retrieved 2010–08–09.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "The Liberty Bell" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved 2010–08–11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The Franklin Institute, p. 21

- ^ Greiff, p. 14

- ^ Nash, pp. 114–117

- ^ a b c d "Replicas of the Liberty Bell owned by U.S. state governments". Liberty Bell Museum. Retrieved 2010–08–11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "states" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Hudgeons, p. 493

- ^ Hudgeons, p. 389

- ^ Hudgeons, p. 413

- ^ Nash, p. 126

- ^ Annual Report of the Postmaster General. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1926. p. 6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Save forever on postage price increases with Forever Stamps". United States Postal Service. 2008–05–08. Retrieved 2010–08–11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Nash, p. 184

- ^ Nash, p. 183

- ^ Ahuja, Jay (2001). Fields of Dreams: A Guide to Visiting and Enjoying All 30 Major League Ballparks. Citadel Press. p. 62. ISBN 0806521937. Retrieved 2010–08–11.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nash, pp. 141–143

- ^ a b Paige, p. 9

Bibliography

- de Bolla, Peter (2008). The Fourth of July and the Founding of America. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1-58567-933-1.

- The Franklin Institute. (1962). Report of the Committee for the Preservation of the Liberty Bell (Report). Philadelphia, PA: The Franklin Institute. (reprinted in The Journal of the Franklin Institute, Volume 275, Number 2, February 1963), obtained from Independence National Historical Park Library and Archive, 143 S. 3rd St., Philadelphia PA 19106)

- Greiff, Constance M. (1987). Independence: The Creation of a National Park. Philadelphia, Pa.: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812280474.

- Hanson, Victor F. (1975). Analysis of the Liberty Bell: Analytical Laboratory Report #379 (Report). Winterthur, DE: Winterthur Museum.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) (obtained from Independence National Historical Park Library and Archive, 143 S. 3rd St., Philadelphia PA 19106) - Hudgeons Jr., Tom (2009). The Official Blackbook Price Guides to United States Coins 2010 (48th ed.). New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 0375723188.

- Kimball, David (2006). The Story of the Liberty Bell (revised ed.). Washington, DC: Eastern National (National Park Service). ISBN 0915992434.

- Nash, Gary B. (2010). The Liberty Bell. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300139365.

- Paige, John C. (1988). Kimball, David C. (ed.). The Liberty Bell: A Special History Study (Report). Denver, CO: National Park Service (Denver Service Center and Independence National Historical Park). (obtained from Independence National Historical Park Library and Archive, 143 S. 3rd St., Philadelphia PA 19106)

External links

- Liberty Bell Center. Independence National Historical Park. National Park Service official website

- The Liberty Bell: From Obscurity to Icon, a National Park Service Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan. National Park Service official website

- Liberty Bell Center, National Park Service. Bohlin Cywinski Jackson (architects) website. Retrieved 2010–03–16.