Liu Hong (Jin dynasty)

Liu Hong | |

|---|---|

| 劉弘 | |

| Inspector of Jingzhou (荊州刺史) | |

| In office 303–306 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 236 Suixi County, Anhui |

| Died | 306 (aged 69–70) Xiangyang, Hubei |

| Relations | Liu Fu (grandfather) |

| Children | Liu Fan |

| Parent | Liu Jing |

| Occupation | Governor |

| Courtesy name | Heji (和季) Shuhe (叔和) |

| Peerage | Duke of Xuancheng (宣城公) |

| Posthumous name |

|

Liu Hong (236–306), courtesy name Heji or Shuhe,[1] was a military general and politician of the Jin dynasty (266–420). He was most known for his role as Inspector of Jingzhou between 303 and 306. After quelling the revolt of Zhang Chang, Liu Hong ushered Jingzhou into a brief period of peace and stability, making it a haven for refugees fleeing the various conflicts happening throughout most parts of China at the time. His administration made him a revered figure among the people, and traditional historians praised him as a model governor.

Early life and career[edit]

Liu Hong was from Pei State, Xiang Commandery (相郡), which is around present-day Suixi County, Anhui. His grandfather was Liu Fu, an official under the late Han dynasty warlord Cao Cao and his father was Liu Jing, a minister in the Cao Wei dynasty. During his youth, Liu Hong resided in Luoyang, where he was classmates with the future Emperor Wu of Jin, Sima Yan. In 266, Sima Yan usurped the Wei throne and established the Jin dynasty. Due to their past acquaintanceship, Sima Yan appointed Liu Hong Grandee at the Gate of the Heir Apparent as a token of friendship.[2]

The Book of Jin describes Liu Hong as someone who excelled at strategy and statecraft. He served in a series of offices and was even an Army Advisor to the general Yang Hu at one point.[3] Eventually, Liu Hong caught the attention of the prominent minister, Zhang Hua. Zhang Hua recommended Liu Hong to serve in the northern borders of Yuzhou as General Who Guards The Northern Frontier. In the north, Liu Hong asserted his authority, and reportedly, bandit activities in the region were near to none under him. For his conduct, the people and officials praised Liu Hong, and the court awarded him the title of "Duke of Xuancheng".[4]

Zhang Chang's rebellion[edit]

In 303, a powerful revolt led by Zhang Chang broke out in Jingzhou. The Chief Controller of Jingzhou, Sima Xin (司馬歆), requested the court for reinforcements to help against the rebels. The court appointed Liu Hong as Inspector of Jingzhou and sent him, among others, to aid Sima Xin. Liu Hong and his fellow generals camped at Wancheng, but not long after, the rebels killed Sima Xin at Fancheng. The court chose Liu Hong to be Sima Xin's replacement, granting him the offices of General Who Guards The South and Chief Controller of Jingzhou.[5] Liu Hong marched to the provincial capital of Xiangyang, but when Zhang Chang took the city of Wancheng, he retreated to camp at Liang County (梁縣; in present-day Ruzhou, Henan).

Later in the year, Zhang Chang's rebellion spread to Jiangzhou, Xuzhou, Yangzhou and Yuzhou. Liu Hong sent a group of generals, including Tao Kan, to attack Zhang Chang at Jingling while sending another group consisting of Li Yang (李楊) to capture Jiangxia. Tao Kan's group defeated Zhang Chang numerous times, and after a decisive victory, they forced Zhang Chang into hiding while his army surrendered to the Jin forces. Tao Kan distinguished himself in quelling the rebellion, which made him highly regarded by Liu Hong.[3]

While Liu Hong was away, a general, Zhang Yi (張奕), was appointed by Jin to govern Xiangyang in his absence. With Zhang Chang no longer a threat, Liu Hong decided to return to Xiangyang and take control of Jingzhou. However, Zhang Yi refused to give up his position and began rallying his troops against Liu Hong. Liu Hong quickly marched to Xiangyang and beheaded Zhang Yi.[6] He then reported the incident to the court, and the court ruled to exempt him from punishment. Liu Hong would only capture Zhang Chang in the spring of 304, after which he executed him and sent his head to the capital.

Administration of Jingzhou[edit]

Policies and reforms[edit]

One of the first problems faced by Liu Hong upon retaking Xiangyang was a shortage of officials in the local government. To rectify this issue, Liu Hong asked and received the court's consent to personally hand out appointments so he could fill the vacant offices. Liu Hong reputedly appointed his candidates based on their merits and virtue.[7] One case was his appointment of Pi Chu (皮初). Liu Hong wanted Pi Chu to be the Administrator of Xiangyang due to his merits, but the court, noting Pi Chu's lack of influence, opted for Liu Hong's son-in-law, Xiahou Zhi (夏侯陟). Liu Hong, rhetorically asked, "There are ten commanderies in Jingzhou. If it is necessary that who I appoint must be married into my family, must I have ten son-in-laws before I could govern Jingzhou?" He sent a petition to the court asking Pi Chu to be justly rewarded while also pointing out that, as per tradition, he and a promoted relative by marriage cannot have mutual supervision over one another. The court agreed and gave the appointment to Pi Chu.[8]

Liu Hong carried out several effective policies to improve the standard of living in Jingzhou. He allowed the people to fish at the lakes of Mount Xian (峴山; in present-day Xiangyang, Hubei) and Mount Fang (方山; in present-day Chibi, Hubei), which an ancient law had previously prohibited.[9] Then, Liu Hong abolished the categorization of alcohol into qizhong liquor (齊中酒; for religious purposes), tingshi liquor (聽事酒; for officials) and wei liquor (猥酒; for peasants), permitting everyone to consume any sorts of alcohol as they please.[10] Liu Hong heavily encouraged farming and sericulture to the people. He also lightened the severity of punishments and reduced taxes. These policies made Liu Hong a beloved figure in Jingzhou.[11]

Assisting Luo Shang and refugees[edit]

In 304, the rebel leader, Li Xiong, ousted the Jin Inspector of Yizhou, Luo Shang, out from Chengdu. Luo Shang relocated himself to Jiangyang, where he requested food supply from Liu Hong. Liu Hong's account-keepers advised Liu Hong to give Luo Shang only 5,000 hú (斛) of rice, citing the long distance between the two governors and the food shortages in Jingzhou. However, Liu Hong wanted to ensure that Luo Shang would secure Jingzhou's western borders.[12] Instead, he sent 30,000 hú of rice to Luo Shang and ordered his general, He Song (何松), to camp at Badong and serve as Luo Shang's reserve force.

At the same time, refugees were coming into Jingzhou to escape the wars and rebellions happening throughout China. These refugees often had to resort to banditry due to poverty. However, Liu Hong curbed this issue by distributing fields and seeds to the refugees.[13] He also sought out talents among the refugees and appointed them to offices based on their capabilities. Due to his broad influence, an official of Liu Hong, Xin Ran (辛冉), recommended that he attempt to break away from Jin, but Liu Hong, in anger, had him executed.[14]

Among those who fled to Jingzhou were performers of the imperial music bureau. Liu Hong's subordinates suggested that they invite the performers to play music for them. However, Liu Hong refused and alluded to the story of Du Kui and Liu Biao, believing that it would be inappropriate for him as a minister to have imperial music performed in his own court especially during a time of crisis. He comforted the performers by allowing them to settle in the commanderies and counties and returned them once the situation in the imperial court was stable.[15]

War of the Eight Princes[edit]

In 305, the Prince of Donghai, Sima Yue, initiated a coalition to overthrow Emperor Hui of Jin's regent, the Prince of Hejian, Sima Yong. The Inspector of Yuzhou, Liu Qiao, joined the war on the side of Sima Yong, so the court published an edict calling for generals, including Liu Hong, to aid Liu Qiao against the coalition. Liu Hong was worried that the war would undermine the imperial family, so he wrote letters to Sima Yue and Liu Qiao, persuading them to stop, but neither side accepted his proposal. He then wrote a petition to the Jin court to convince Sima Yong to seek peace with Sima Yue. However, Sima Yong also dismissed him.[16] With war being inevitable, Liu Hong decided to side with Sima Yue as he was appalled by Sima Yong's controversial marshal, Zhang Fang and believed Zhang Fang would bring about Sima Yong's downfall. Thus, Liu Hong sent an envoy to Sima Yue to convey his allegiance to him.[17]

Chen Min's rebellion[edit]

At the end of 305, the Chancellor of Guangling, Chen Min, rebelled against Jin in the Jiangnan region. Liu Hong responded by sending Tao Kan and the Administrator of Wuling, Miao Guang (苗光), to camp at Xiaokou. However, there were suspicions about Tao Kan, as he was from the same commandery as Chen Min, and the two became officials around the same time. The Interior Minister of Sui, Hu Huai (扈懷), brought this matter to Liu Hong, but Liu Hong did not believe him. When Tao Kan heard about the allegations, he sent his son, Tao Hong (陶洪), and his nephew, Tao Zhen (陶臻), to explain his position. After asking the two for military advice, Liu Hong sent Tao Hong and Tao Zhen back with gifts, expressing his earnest trust in Tao Kan.[18] When Chen Min invaded Jingzhou, Tao Kan joined with the other Jin generals in repelling him. In the end, the Jin forces thwarted Chen Min's ambitions to conquer Jingzhou.

As Chen Min's forces withdrew, the Administrator of Nanyang, Wei Zhan (衞展), advised Liu Hong to kill the general Zhang Guang, who, although had helped in defending Jingzhou, was friends with Sima Yong. Wei Zhan believed that killing Zhang Guang would show Liu Hong's loyalty to Sima Yue, but Liu Hong dismissed the suggestion. Instead, he sent a petition to the court asking them to promote Zhang Guang for his contributions.[19]

Death and posthumous events[edit]

In 306, Liu Hong intercepted the Prince of Chengdu, Sima Ying, from escaping to his fiefdom after Sima Yue's forces defeated him. Later, Sima Yue took Chang'an from Sima Yong and moved Emperor Hui to Luoyang. Liu Hong sent Liu Pan (劉盤) with troops to welcome the emperor back to the emperor. After Liu Pan returned from his commission, Liu Hong considered retiring due to his old age and wrote a letter to the court asking to divide his offices among his subordinates. However, before he could retire, Liu Hong died in Xiangyang. The people and officials of Jingzhou mourned Liu Hong's death as if they had lost a parent.[20]

Soon after his death, Liu Hong's former marshal, Guo Mai (郭勱), rebelled and intended to make Sima Ying the leader. However, Liu Hong's son Liu Fan (劉璠) and general Guo Shu (郭舒) campaigned against Guo Mai and killed him. Liu Hong and Liu Fan's loyalty pleased Sima Yue, who wrote a letter of gratitude to Liu Fan. The court posthumously named him "Duke of Xincheng" and "Yuan" (元).

The Prince of Gaomi, Sima Lue (司馬略), succeeded Liu Hong as Inspector of Jingzhou, but Lue was not as capable as Liu Hong, and Jingzhou saw a rise in dissidents and bandits. To appease the people, the court appointed Liu Fan as the Interior Minister of Shunyang (順陽; south of present-day Xichuan County, Henan). Liu Fan was just as beloved as his father, so the people living between the Han and Yangzi rivers began moving to live under Liu Fan. However, after Sima Lue died, his successor, Shan Jian, fearful that Liu Fan would use his popularity to rebel, requested the court to move Liu Fan to Luoyang. Shan Jian was a neglectful administrator, and his decision against Liu Fan proved unpopular with the people. Eventually, uprisings sprang up in the south, the most notable being the one led by Du Tao. As the situation in the south deteriorated, the people reportedly longed for Liu Hong's governance.[21]

Liu Hong's tomb[edit]

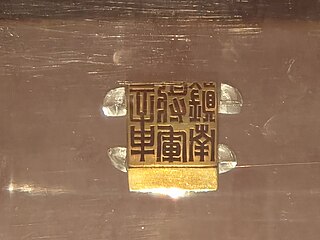

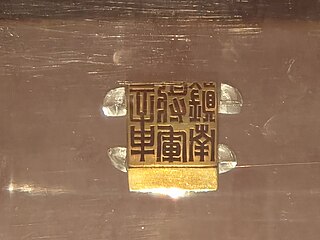

In March 1991, Liu Hong's tomb was discovered in Anxiang County, Hunan. Two gold seals with tortoise-shaped knobs, one titled "Seal of the General Who Guards the South" (鎮南將軍章) and another titled "Seal of the Duke of Xuancheng" (宣成公章), were among the artefacts excavated from the tomb.[22]

-

Golden Seal of Duke of Xuancheng

Golden Seal of Duke of Xuancheng -

Golden Seal of the General Who Guards the South

Golden Seal of the General Who Guards the South

References[edit]

- ^ According to the Book of Jin, Liu Hong's courtesy name is Heji. However, Pei Songzhi's commentary in Sanguozhi, volume 15 cites the Chronicles of Jinyang (晉陽秋) which states that Liu Hong's courtesy name is Shuhe.

- ^ (...少家洛陽,與武帝同居永安裏,又同年,共研席。以舊恩起家太子門大夫...) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ a b (旣克張昌,劉弘謂侃曰:「吾昔爲羊公參軍,謂吾後當居身處。今觀卿,必繼老夫矣。」) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 85

- ^ (由是為甯朔將軍、假節、監幽州諸軍事,領烏丸校尉,甚有威惠,寇盜屏跡,為幽朔所稱。以勳德兼茂,封宣城公。) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (詔以劉弘代歆爲鎭南將軍,都督荊州諸軍事。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 85

- ^ (初,弘之退也,范陽王虓遣長水校尉張奕領荊州。弘至,奕不受代,與兵距弘。弘遣軍討奕,斬之...) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (時荊部守宰多缺,弘請補選,詔許之。弘敍功銓德,隨才授任,人皆服其公當。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 85

- ^ (弘表皮初補襄陽太守,朝廷以初雖有功而望淺,更以弘壻前東平太守夏侯陟爲襄陽太守。弘下敎曰:「夫治一國者,宜以一國爲心,必若親姻然後可用,則荊州十郡,安得十女壻然後爲政哉!」乃表:「陟姻親,舊制不得相監;皮初之勳,宜見酬報。」詔聽之。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 85

- ^ (舊制,峴方二山澤中不聽百姓捕魚,弘下教曰:「禮,名山大澤不封,與共其利。今公私並兼,百姓無復厝手地,當何謂邪!速改此法。」) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (「酒室中雲齊中酒、聽事酒、猥酒,同用曲米,而優劣三品。投醪當與三軍同其薄厚,自今不得分別。」) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (弘於是勸課農桑,寬刑省賦,歲用有年,百姓愛悅。) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (...弘綱紀以運道阻遠,且荊州自空乏,欲以零陵米五千斛與尚。弘曰:「天下一家,彼此無異,吾今給之,則無西顧之憂矣。」) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 84

- ^ (于時流民在荊州者十餘萬戶,羈旅貧乏,多爲盜賊,弘大給其田及種糧,擢其賢才,隨資敍用,流民遂安。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 84

- ^ (前廣漢太守辛冉說弘以從橫之事,弘大怒,斬之。) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (時總章太樂伶人,避亂多至荊州,或勸可作樂者。弘曰:「昔劉景升以禮壞樂崩,命杜夔為天子合樂,樂成,欲庭作之。夔曰:'為天子合樂而庭作之,恐非將軍本意。'吾常為之歎息。今主上蒙塵,吾未能展效臣節,雖有家伎,猶不宜聽,況禦樂哉!」乃下郡縣,使安慰之,須朝廷旋返,送還本署。) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (劉弘遺喬及司空越書,欲使之解怨釋兵,同獎王室,皆不聽。弘又上表曰:「...」時太宰顒方拒關東,倚喬爲助,不納其言。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 86

- ^ (劉弘以張方殘暴,知顒必敗,乃遣參軍劉盤爲都護,帥諸軍受司空越節度。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 86

- ^ (隨郡內史扈懷言於弘曰:「侃居大郡,統強兵,脫有異志,則荊州無東門矣!」弘曰:「侃之忠能,吾得之已久,必無是也。」侃聞之,遣子洪及兄子臻詣弘以自固,弘引爲參軍,資而遣之。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 86

- ^ (南陽太守衞展說弘曰:「張光,太宰腹心,公旣與東海,宜斬光以明向背。」弘曰:「宰輔得失,豈張光之罪!危人自安,君子弗爲也。」乃表光殊勳,乞加遷擢。) Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 86

- ^ (盤既旋,弘自以老疾,將解州及校尉,適分授所部,未及表上,卒於襄陽。士女嗟痛,若喪所親矣。) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ (南夏遂亂。父老追思弘,雖《甘棠》之詠召伯,無以過也。) Jin Shu, vol. 66

- ^ "Gold Seal with Tortoise-shaped Knob | 湖南省博物館". www.hnmuseum.com. Retrieved 2022-05-30.

- Fang, Xuanling (ed.) (648). Book of Jin (Jin Shu).

- Sima, Guang (1084). Zizhi Tongjian.