Ludwig Leichhardt

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt | |

|---|---|

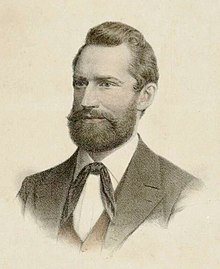

Portrait of Ludwig Leichhardt | |

| Born | 23 October 1813 Sabrodt, Germany (Kingdom of Prussia) |

| Disappeared | April 3, 1848 (aged 34) Darling Downs, Australia |

| Status | Presumed killed |

| Occupation | Explorer |

| Parent(s) | Charlotte Sophie and Christian Hieronymus Leichhardt |

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (German pronunciation: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç 'vɪlhɛlm 'lu:tvɪç 'laɪçhaːʁt]), known as Ludwig Leichhardt, (23 October 1813 – c.1848)[1] was a Prussian explorer and naturalist, most famous for his exploration of northern and central Australia.[2]

Biography

Early life

Leichhardt was born on 23 October 1813 in the village of Trebatsch, today part of Tauche, in the Prussian Province of Brandenburg.[3] He was the fourth son and sixth of the eight children of Christian Hieronymus Matthias Leichhardt, farmer and royal inspector and his wife Charlotte Sophie, née Strählow.[1] Between 1831 and 1836 Leichhardt studied philosophy, language, and natural sciences at the Universities of Göttingen and Berlin but never received a university degree. He moved to England in 1837, continued his study of the natural sciences at various places, including the British Museum, London, and the Jardin des Plantes, Paris, and undertook field work in several European countries, including France, Italy and Switzerland.

Explorer

On 14 February 1842 Leichhardt arrived in Sydney, Australia. His aim was to explore inland Australia and he was hopeful of a government appointment in his fields of interest.[4] In September 1842 Leichhardt went to the Hunter River valley north of Sydney to study the geology, flora and fauna of the region, and to observe farming methods. He then set out on his own on a specimen-collecting journey that took him from Newcastle, New South Wales, to Moreton Bay in Queensland.

After returning to Sydney early in 1844, Leichhardt hoped to take part in a proposed government-sponsored expedition from Moreton Bay to Port Essington (300 km north of Darwin, Northern Territory). When plans for this expedition fell through Leichhardt decided to mount the expedition himself, accompanied by volunteers and supported by private funding. His party left Sydney in August 1844 to sail to Moreton Bay, where four more joined the group. The expedition departed on 1 October 1844 from Jimbour Homestead, the farthest outpost of settlement on the Queensland Darling Downs.

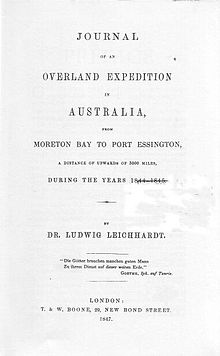

After a nearly 4,800 kilometres (3,000 miles) overland journey, and having long been given up for dead, Leichhardt arrived in Port Essington on 17 December 1845. He returned to Sydney by boat, arriving on 25 March 1846 to a hero's welcome. The Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia, from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, a Distance of Upwards of 3000 km, During the Years 1844 and 1845 by Leichhardt describes this expedition.

A memorial to John Gilbert, one of Leichhardt's companions on this journey, can be found on the north wall of St James' Church, Sydney. Under the title Dulce et Docorum Est Pro Scientia Mori (a variation on the more commonly seen Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori) the inscription on the monument, which was "erected by the colonists of New South Wales" reads: "in memory of John Gilbert, Ornithologist, who was speared by the blacks on 29 June 1845 during the first overland expedition to Port Essington by Dr Ludwig Leichhardt and his intrepid companions". There is also a memorial to Gilbert at Gilbert's Lookout at Taroom.[5]

Leichhardt's second expedition, undertaken with a government grant and substantial private subscriptions, started in December 1846. It was supposed to take him from the Darling Downs to the west coast of Australia and ultimately to the Swan River and Perth. However, after covering only 800 km the expedition team was forced to return in June 1847 due to heavy rain, malarial fever and famine. After recovering from malaria Leichhardt spent six weeks in 1847 examining the course of the Condamine River, southern Queensland, and the country between the route of another expedition led by Sir Thomas Mitchell in 1846 and his own route, covering nearly 1,000 km.

In April 1847 Leichhardt shared the annual prize of the Paris Geographical Society, for the most important geographic discovery with French explorer Charles-Xavier Rochet d'Héricourt. Soon afterward, on 24 May, the Royal Geographical Society, London, awarded Leichhardt its Patron's Medal as recognition of 'the increased knowledge of the great continent of Australia' gained by his Moreton Bay-Port Essington journey.[1] Leichhardt himself never saw these medals but was aware he had been awarded them. In one of his last known letters he wrote:[6]

- I've had the pleasure of hearing that the geographical society in London has awarded me one of its medals, and that the Parisian geographical society has conferred a similar honour upon me. Naturally I'm very pleased to think that such discerning authorities consider me worthy of such honour; but whatever I have done has never been for honour. I have worked for the sake of science, and for nothing else.[4]

In 2012 the National Museum of Australia purchased the medal awarded to Leichhardt by London's Royal Geographical Society in 1847. It came directly from descendants of the Leichhardt family in Mexico.[4]

Disappearance

In 1848 Leichhardt again set out from the Condamine River to reach the Swan River. The expedition consisted of Leichhardt, four Europeans, two Aboriginal guides, seven horses, 20 mules and 50 bullocks.The Europeans were Adolph Classen, Arthur Hentig, Donald Stuart and Thomas Hands, a ticket of leave holder who replaced Kelly at Henry Stuart Russell's Cecil Plains station. The Aboriginal guides were Wommai and Billy Bombat, from Port Stephens.[7][8]

The party was last seen on 3 April 1848 at Allan Macpherson's station, Cogoon, on the Darling Downs. Leichhardt's disappearance after moving inland, although investigated by many, remains a mystery. The expedition had been expected to take two to three years, but after no sign or word was received from Leichhardt it was assumed that he and the others in the party had died. The latest evidence suggests that they may have perished somewhere in the Great Sandy Desert of the Australian interior.[2]

Four years after Leichhardt's disappearance the Government of New South Wales sent out a search expedition under Hovenden Hely. The expedition found nothing but a single campsite with a tree marked "L" over "XVA". In 1858 another search expedition was sent out, this time under Augustus Gregory. This expedition found only a couple of trees marked "L".

In 1864 Duncan McIntyre discovered two trees marked with "L" on the Flinders River near the Gulf of Carpentaria. After his return to Victoria McIntyre telegraphed the Royal Society on 15 December 1864 that he had found "two trees marked L about 15 years old".[9] He was subsequently appointed leader of a search expedition, but found no further trace of Leichhardt.

In 1869 the Government of Western Australia heard rumours of a place where the remains of horses and men killed by indigenous Australians could be seen. A search expedition was sent out under John Forrest, but nothing was found, and it was decided that the story might refer to the bones of horses left for dead at Poison Rock during Robert Austin's expedition of 1854.

The mystery of Leichhardt's fate remained in the minds of explorers for many years. During David Carnegie's expedition through the Gibson and Great Sandy Deserts in 1896 he encountered some Aborigines who had among their possessions an iron tent peg, the lid of a tin matchbox and part of the ironwork of a saddle. Carnegie speculated that these were from Leichhardt's expedition. Except for a small brass plate that was found in 1900 bearing Leichhardt's name, "no artefacts with corroborated provenance have been able to shed light on Leichhardt's final expedition".[4]

In 1975, a ranger named Zac Mathias exhibited photographs in Darwin of aboriginal cave paintings that showed white men with an animal.[10]

The Leichhardt nameplate

In 2006 Australian historians and scientists authenticated a tiny brass plate (15 cm × 2 cm) marked "LUDWIG LEICHHARDT 1848",[11][12] discovered around 1900 by an Aboriginal stockman near Sturt Creek, between the Tanami and Great Sandy deserts, just inside Western Australia from the border with the Northern Territory. When found, the plate was attached to a partially burnt shotgun slung in a boab tree which was engraved with the initial "L". The plate is now part of the National Museum of Australia collection.[13]

Before the nameplate was authenticated, historians could only speculate on the route Leichhardt had taken and how far he had journeyed before perishing. The location of the plate indicated that he made it at least two thirds of the way across the continent during his east-west crossing attempt. It also suggested that he was following a northern arc from Moreton Bay in Queensland to the Swan River in Western Australia, following the headwaters of rivers, rather than heading straight through the desert interior.[14][15]

Aboriginal oral history

In 2003, a librarian found a letter in the NSW State Library that may shed light on Leichhardt's disappearance. Dated 2 April 1874, the letter, received by Sydney clergyman William Branwhite Clarke, was written by W.P. Gordon, a station owner from the Darling Downs who had met Leichhardt in the days before his party vanished. The letter relates how Gordon moved to Wallumbilla and how, after living there for more than 10 years, he had befriended the Wallumbilla tribe who now openly shared their stories and folklore with him. One detailed story referred to the death of a white man who was leading a party of mules and bullocks along the Maranoa River many years earlier. According to the Wallumbilla, a large group of Aboriginals had encircled the party and murdered everyone in it. It has been speculated that if the story was true, the expedition's belongings were likely traded widely after the massacre, explaining how items that could only have come from Leichhardt's expedition were found in the Gibson Desert and why the rifle butt with the brass plate was found some 4,000 kilometres west of the Maranoa River.[16]

Theories

The validity of all the claimed 'Leichhardt' relics and the various theories proposed are summarised and assessed in a 2013 book entitled Where is Dr Leichhardt?: the greatest mystery in Australian history.[17]

Legacy

Leichhardt's contribution to science, especially his successful expedition to Port Essington in 1845, was officially recognised. In 1847 the Geographical Society, Paris, awarded its annual prize for geographic discovery equally to Leichhardt and a French explorer, Rochet d'Héricourt; also in 1847, the Royal Geographical Society in London awarded Leichhardt its Patron's Medal; and Prussia recognised his achievement by granting him a king's pardon for having failed to return to Prussia when due to serve a period of compulsory military training. The Port Essington expedition was one of the longest land exploration journeys in Australia, and a useful one in the discovery of excellent pastoral country.[1]

Harsh criticism of Leichhardt's character was published some time after his disappearance and his reputation suffered badly. The fairness of this criticism continues to be debated. Nevertheless, Leichhardt's accounts and collections were valued, and his observations are generally considered to be accurate. He is remembered as one of the most authoritative early recorders of Australia's environment and the best trained natural scientist to explore Australia to that time.[2][18] Leichhardt left a record of his observations in Australia from 1842 to 1848 in diaries, letters, notebooks, sketch-books, maps, and in his published works.[1]

Leichhardt's failed attempt to make the first east–west crossing of the Australian continent may be compared with the Burke and Wills expedition of 1860-61, which succeeded in crossing from south to north, but failed to return. However, Leichhardt's success in making it to Port Essington in 1845 was a major achievement, which ranks him with other successful European explorers of Australia.[4]

Australia has commemorated Ludwig Leichhardt through the use of his name in several places: Leichhardt, a suburb in the Inner West of Sydney, and the surrounding Municipality of Leichhardt; Leichhardt, a suburb of Ipswich; the Leichhardt Highway and the Leichhardt River in Queensland; and the Division of Leichhardt in the Australian Parliament. A species of Eucalyptus tree bears Leichhardt's name and the insect Petasida ephippigera is commonly known as Leichhardt's grasshopper.[19]

Leichhardt's life inspired a range of "Lemurian" novels, starting with George Firth Scott's book The Last Lemurian (1898). His last expedition was the inspiration for the 1957 novel Voss by Patrick White.[20]

On 23 October 1988, a monument was erected beside Leichhardts' blazed tree at Taroom by the local historical society and tourism association to celebrate Leichhardt's 175th birthday and the Bicentenary of Australia.[2] The tree was listed on the Queensland Heritage Register in 1992.[21]

In February 2013 the band Manilla Road released a song called Mysterium, based on Leichhardt's explorations and disappearance.[22]

Letters from Leichhardt to his fellow expedition team member Frederick Isaac are held in the State Library of New South Wales.[23][24]

Published works

- Leichhardt, Ludwig (1847), Journal of an overland expedition in Australia, from Moreton Bay to Port Essington, a distance of upwards of 3000 miles, during the years 1844–1845, T. & W. Boone, available online

References

- ^ a b c d e Erdos, Renee (1967). Leichhardt, Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig (1813–1849) (2: 1788–1850 I-Z ed.). Melbourne: Australian National University. pp. 102–104. ISBN 0-522-84236-4.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Ken Eastwood, ''Cold case: Leichhardt's disappearance', Australian Geographic, AG Online, accessed online 7 August 2010

- ^ "FINDING LEICHHARDT". The Sydney Morning Herald. National Library of Australia. 12 September 1865. p. 8. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e The Leichhardt nameplate and medal, National Museum of Australia, accessed online 18 March 2011

- ^ "John Gilbert". Monument Australia. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Ludwig Leichhardt's Australian letters". www.environmentandsociety.org. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ Leichhardt, Ludwig (14 March 1848). "Autograph letter signed from Ludwig Leichhardt to ?". Manuscripts, Oral History and Pictures. Sydney: State Library of New South Wales. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Smout, Ruth (1966). "Leichhardt : the secrets of the Sandhills : a legend and an enigma" (pdf). Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. 8 (1). Brisbane, Qld: Royal Historical Society of Queensland: 59. ISSN 0085-5804. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Vol 25, Part 1, Oct 1987, p9

- ^ Marshall, Richard (1982). Mysteries of the unexplained (Repr. with amendments ed.). Pleasantville, N.Y.: Reader's Digest Association. p. 120. ISBN 0-89577-146-2.

- ^ Scientific analysis of the Leichhardt nameplate, Paper presented by David Hallam, Senior Conservator, National Museum of Australia, Leichhardt symposium, 15 June 2007

- ^ "Ludwig Leichhardt: A German Explorer's Letters Home from Australia: Introduction". www.environmentandsociety.org. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Nameplate for Ludwig Leichhardt 1848, National Museum of Australia collection record". Nma.gov.au. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ "Small clue reveals explorer's huge endeavour". The Age – online. 24 September 2006.

- ^ He nearly made it: Leichhardt's 'grand plan' of 1848, Paper presented by Dr Darrell Lewis, Australian National University, Leichhardt Symposium, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, Friday, 15 June 2007

- ^ Munro, Chris (19 March 2012). "The enduring mystery of Ludwig Leichhardt". Tracker (news service published by the NSW Aboriginal Land Council). Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Darrell (2013). Where is Dr Leichhardt?: the greatest mystery in Australian history. Clayton, Victoria: Monash University Publishing. ISBN 9781921867767.

- ^ Leichhardt as scientist and diarist, Paper presented by Dr Tom Darragh, Museum Victoria, Leichhardt symposium, National Museum of Australia, 15 June 2007

- ^ Corymbia leichhardtii, EUCLID: Eucalypts of Australia, Australian National Botanic Gardens, accessed online 15 March 2011

- ^ Leichhardt in Australian literature, Paper presented by Dr Susan Martin, La Trobe University, Leichhardt symposium, National Museum of Australia, 15 June 2007

- ^ "Leichhardt Tree (entry 600835)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Manilla Road – Mysterium – Encyclopaedia Metallum". The Metal Archives. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ^ Leichhardt, Ludwig, 1813–1848 (1844), Item 12: Autograph letter signed from Ludwig Leichhardt to Frederick Isaac, 3 June 1844, retrieved 5 April 2015

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Leichhardt, Ludwig, 1813–1848 (1847), Item 14: Autograph letter signed from Ludwig Leichhardt to Frederick Isaac, 10 October 1847, retrieved 5 April 2015

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Bibliography

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Leichhardt, Ludwig". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- Stephens, Matthew (October 2007). "From Lost Property to Explorer's Relics : The Rediscovery of the Personal Library of Ludwig Leichhardt". Historical Records of Australian Science. 18 (2): 191–227. doi:10.1071/HR07008. ISSN 0727-3061.

- Lewis, Darrell (2006). "The Fate of Leichhardt". Historical Records of Australian Science. 17 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1071/HR05010. ISSN 0727-3061.

- Colin Roderick: "Leichhardt, the dauntless explorer", North Ryde (Sydney): Angus & Robertson 1988, ISBN 0-207-15171-7

- Nicholls, Angus (2011). Discussion of Leichhardt's influence on Patrick White's novel Voss, ABC Radio National Book Show, 25 January [1]

- Nicholls, Angus (2012). "The Core of this Dark Continent: Ludwig Leichhardt's Australian Explorations", in Transnational Networks: Germans in the British Empire 1670-1914, ed. John R. Davis, Stefan Manz and Margrit Schulte Beerbühl (Leiden: Brill).

- Nicholls, Angus (2013). "The Young Leichhardt's Diaries in the Context of his Australian Cultural Legacy", in Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture 7, no. 2, 541-59

- Boase, George Clement (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 32. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

External links

- A complete written version of Leichhardt's expedition- [2]

- Works by Ludwig Leichhardt at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Ludwig Leichhardt at Project Gutenberg Australia

- Works by or about Ludwig Leichhardt at the Internet Archive

- Ludwig Leichhardt online collection – State Library of NSW

- Ludwig Leichhardt series, National Museum of Australia Audio on Demand: Papers presented to the Leichhardt symposium, National Museum of Australia, 15 June 2007

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Journal of an Overland Expedition in Australia