Maccabean Revolt

| Maccabean Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

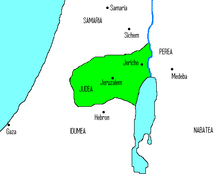

Judea under Judas Maccabeus during the revolt | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Mattathias Judah Maccabee (KIA) Jonathan Apphus Eleazar Avaran (KIA) Simon Thassi John Gaddi (KIA) |

Antiochus IV Epiphanes Antiochus V Eupator Demetrius I Soter Lysias Gorgias Nicanor (KIA) Bacchides | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Judean/Maccabean rebels | Seleucid army | ||||||

The Maccabean Revolt (Template:Lang-he; Template:Lang-el) was a Jewish rebellion, lasting from 167 to 160 BC, led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and the Hellenistic influence on Jewish life.

Timeline

In the narrative of I Maccabees, after Antiochus issued his decrees forbidding Jewish religious practice, a rural Jewish priest from Modiin, Mattathias the Hasmonean, sparked the revolt against the Seleucid Empire by refusing to worship the Greek gods. Mattathias killed a Hellenistic Jew who stepped forward to offer a sacrifice to an idol in Mattathias' place. He and his five sons fled to the wilderness of Judah. After Mattathias' death about one year later in 166 BC, his son Judah Maccabee led an army of Jewish dissidents to victory over the Seleucid dynasty in guerrilla warfare, which at first was directed against Hellenized Jews, of whom there were many. The Maccabees destroyed pagan altars in the villages, circumcised boys and forced Hellenized Jews into outlawry.[1] The term Maccabees as used to describe the Jewish army is taken from the Hebrew word for "hammer".[2]

The revolt itself involved many battles, in which the light,quick and mobile Maccabean forces gained notoriety among the slow and bulky Seleucid army,and also for their use of guerrilla tactics. After the victory, the Maccabees entered Jerusalem in triumph and ritually cleansed the Temple, reestablishing traditional Jewish worship there and installing Jonathan Maccabee as high priest. A large Seleucid army was sent to quash the revolt, but returned to Syria on the death of Antiochus IV. Its commander Lysias, preoccupied with internal Seleucid affairs, agreed to a political compromise that restored religious freedom.

Battles

- Battle of Wadi Haramia (167 BC)

- Battle of Beth Horon (166 BC)

- Battle of Emmaus (166 BC)

- Battle of Beth Zur (164 BC)

- Battle of Beth Zechariah (162 BC)

- Battle of Adasa (161 BC)

- Battle of Elasa (160 BC)

Studies

In the First and Second Books of the Maccabees, the Maccabean Revolt is described as a response to cultural oppression and national resistance to a foreign power. Modern scholars, however, argue that the king intervened in a civil war between traditionalist Jews in the countryside and Hellenized Jews in Jerusalem.[3][4][5] As Joseph P. Schultz puts it:

"Modern scholarship ... considers the Maccabean revolt less as an uprising against foreign oppression than as a civil war between the orthodox and reformist parties in the Jewish camp."[6]

Professor John Ma of Oxford University argues that the main sources indicate that the loss of religious and civil rights by the Jews in 168 BC was not the result of religious persecution but rather an administrative punishment by the Seleucid Empire in the aftermath of local unrest, and that the Temple was restored upon petition by the High Priest Menelaus, not liberated and rededicated by the Maccabees. However, his theories are speculative.[7]

Legacy

The Jewish festival of Hanukkah celebrates the re-dedication of the Temple following Judah Maccabee's victory over the Seleucids. According to Rabbinic tradition, the victorious Maccabees could only find a small jug of oil that had remained uncontaminated by virtue of a seal, and although it only contained enough oil to sustain the Menorah for one day, it miraculously lasted for eight days, by which time further oil could be procured.[8] The miracle of the oil is widely regarded as a legend and its authenticity has been questioned since the Middle Ages.[9]

See also

References

- ^ Nicholas de Lange (ed.), The Illustrated History of the Jewish People, London, Aurum Press, 1997, ISBN 1-85410-530-2

- ^ The Maccabees/Hasmoneans: History & Overview (166 - 129 BC) Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph (1991). Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know about the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History. W. Morrow. p. 114. ISBN 0-688-08506-7.

- ^ Johnston, Sarah Iles (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- ^ Greenberg, Irving (1993). The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays. Simon & Schuster. p. 29. ISBN 0-671-87303-2.

- ^ Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-8386-1707-7.

- ^ Ma, John. "Re-examining Hanukkah", The Marginalia Review of the Book, July 9, 2013

- ^ Talmud, Tractate Shabbat

- ^ Skolnik, Berenbaum,, Fred, Michael (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica, Volume 9. Granite Hill Publishers, pg 332.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Maccabean Revolt at Oxford Bibliographies

- Maccabean Revolt at the Aish HaTorah website

- Book XII of the Antiquities of the Jews

- Book I of The Jewish War

- 160s BC in Asia

- 2nd-century BC conflicts

- 2nd century BC in the Hasmonean Kingdom

- 2nd-century BCE Judaism

- Coele-Syria

- Jewish rebellions

- Jewish religious nationalism

- Jewish Seleucid history

- Maccabees

- Rebellions against empires

- Rebellions in Asia

- Religion-based wars

- Revolts in Greek Antiquity

- Wars involving the Seleucid Empire

- Wars of ancient Israel