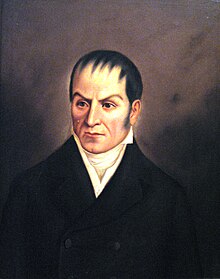

Manuel Rodríguez Torices

Manuel Rodríguez Torices | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor President of the State of Cartagena de Indias | |

| In office April 1, 1812 – October 4, 1812 | |

| Preceded by | José María del Real |

| Succeeded by | None* |

| President of the United Provinces of the New Granada• | |

| In office July 28, 1815 – November 15, 1815 | |

| Preceded by | Triumvirate José María del Castillo y Rada, José Fernández Madrid, Joaquín Camacho |

| Succeeded by | Camilo Torres Tenorio |

| Vice President of the United Provinces of the New Granada | |

| In office November 15, 1815 – March 14, 1816 | |

| President | Camilo Torres Tenorio |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 24, 1788 Cartagena de Indias, Bolívar |

| Died | October 5, 1816 Bogotá, Cundinamarca |

| Political party | Federalist |

| |

Manuel Rodríguez Torices (full birth name Manuel Juan Robustiano de los Dolores Rodríguez Torices y Quiroz) (May 24, 1788 – October 5, 1816) was a Neogranadine statesman, lawyer, journalist, and Precursor of the Independence of Colombia. He was part of the Triumvirate of the United Provinces of New Granada in 1815, and served as Vice President of the United Provinces after the triumvirate. He was executed during the Reign of Terror of Pablo Morillo in 1816.

Early life

[edit]Rodríguez was born on May 24, 1788, in Cartagena de Indias[1] in the Province of Barlovento part of the Viceroyalty of the New Granada, in what is now the Bolívar Department in Colombia. His parents were Don Matías Rodríguez Torices, from Burgos, Spain, and doña María Trinidad Quirós y Navarro de Acevedo, from Santafé de Bogotá.[2] He attended elementary school in Cartagena, and then attended the Our Lady of the Rosary University in Santafé de Bogotá, where he graduated in Law.

He participated in the tertulias of Bogotá, particularly in the Tertulia del Buen Gusto,[3] that was held in the house of Manuela Sanz de Santamaría de Manrique and in which participated other important leaders as Camilo Torres Tenorio, Custodio García Rovira, and José Fernández Madrid, among others.

Thanks to the good relations he made in the Tertulia del Buen Gusto, Rodríguez developed an interest in journalism. In 1809 he co-edited the newspaper Seminario de la Nueva Granada with Francisco José de Caldas.[4]

Independence of Cartagena

[edit]On May 10, 1810, the Ayuntamiento of Cartagena formed a Junta, breaking ties with the Spanish government, but recognizing the regency of the crown. This Junta was the first step for independence in New Granada. The Junta also made an important point in its agenda to spread the revolutionary ideas to establish its power and foment a nationalist spirit among the people. The Junta gave this task to Rodríguez and José Fernández Madrid. On September 10, 1810, Rodríguez and Madrid created the Argos Americano, a political, economical, and literary newspaper with the mission of creating public opinion in favor of the new revolutionary ideas.[5]

On November 11, 1811, the junta declared absolute independence from Spain, the crown, Rodríguez was one of the precursors of the independence, and a member of the Junta, and so was a signer of its Constitution. Rodríguez became Governor President of Cartagena de Indias on April 1, 1812,[6] following the resignation of José María del Real, the Convention of the State of Cartagena granted dictatorial powers to Torices to better handle the situation the State was in.

Rodríguez' main objective while in office was to take control of the royalist province of Santa Marta. Rodríguez, although a fervent patriot, had no military experience, so he enlisted the Frenchman Pierre Labatut and the Spaniard Manuel Cortés Campomanes. Santa Marta fell to the hands of Labatut in early 1814, but the victory was short-lived, and Santa Marta went back to royalist hands.[7]

Because of the strategic position of Cartagena as a port, the early presidents of Cartagena felt the need to develop a strong force to patrol the sea and protect the city, his efforts in doing so, and the continuation by this project by his successors gave birth to what would become the Colombian National Armada. On April 7, 1813, the town of Barlovento, what is now Barranquilla, was given official City status by the government of Rodríguez, and made capital of the Province of Tierraandentro. The decree also issued its Coat of arms, and flag, the flag, would later be used as the flag of the United Provinces.[8]

Another one of Rodríguez' objectives during his presidency was to foment the immigration of foreigners to Cartagena. Rodríguez issued a proclamation inviting "all foreigners except those of Spain to come and settle in Cartagena" this text was printed in Spanish, English, and French. Rodríguez also sent representatives to Louisiana, to recruit new citizens.[9] By also enlisting corsairs and pirates, Rodríguez was able to attack Spanish ships, by giving support to the pirates and welcoming them in the city. Most of the immigrants arrived from Venezuela, which was still under Spanish control. One of those Venezuelans was Simón Bolívar; Bolívar was welcomed by Rodríguez, who gave him command of the Army of Cartagena to support his fight in Venezuela.

Triumvirate

[edit]On October 15, 1814, the Congress of the United Provinces of the New Granada, replaced the presidency of the nation, with a Triumvirate. This triumvirate was to be composed of José Manuel Restrepo, Custodio García Rovira, and Rodríguez.[10] Rodríguez, however, was in Cartagena at the time, so he, and his other colleagues were replaced by José Fernández Madrid, José María del Castillo y Rada, and Joaquín Camacho. Rodríguez, resigned the presidency of Cartagena, and sailed in August to Jamaica in a diplomatic mission.[11]

Upon his return, Rodríguez was sworn in as president of the triumvirate on July 28, 1815, in which he presided together with José Miguel Pey de Andrade, and Antonio Villavicencio.

On October 14, authorities caught Cornelio Rodríguez, a royalist, who confessed the plans about a failed royalist coup, Cornelio Rodríguez also accused members of Congress to support the coup, and among those accused was Rodríguez. Rodríguez stepped down from his presidential post, to let Congress judge those accusations in order to clean his reputation, Congress dismissed the accusations against him and others the next day,[12] finding it difficult that the precursor of the independence of Cartagena and known patriot would think of supporting the royalists.

On November 15, Congress changed the executive power once again, entrusting the executive power to a president and a vice president. Congress then named Camilo Torres Tenorio to become president, and entrusted the vice presidency to Rodríguez.[13]

Capture and execution

[edit]

By 1816, the Spaniards had invaded the New Granada by all sides. The Congress dissolved, and on March 14, 1816, Camilo Torres resigned the presidency, many prominent political and social figures of Bogotá were forced to leave trying to escape the imminent invasion. Camilo Torres Tenorio, Rodríguez, Francisco José de Caldas, and José Fernández Madrid, among others, headed to Buenaventura to sail from there, to Buenos Aires.[14] Unfortunately for the party, the ship they were going to board never arrived, and were forced to turn back to Popayán to wait till the next day. The next day, they were captured by the Spaniards and taken to Bogotá.[15]

On October 4, the prisoners were tried by the War Council established by Pablo Morillo. Rodríguez was sentenced to death in the Plaza Mayor, on October 5, 1816, and his property was confiscated.[16] Together with María Dávila, Count Pedro Felipe de Casa Valencia, and Camilo Torres Tenorio, they were hanged on that day. After they died, their bodies were taken down, and the bodies of Torres and Rodríguez were shot in the head and in the chest respectively,[17] then they were decapitated and dismembered.[18] Rodríguez' head was put inside a metal cage and hung from a 30 feet spear and displayed on the outskirts of the city, where the De La Sabana station now stands, to send a message to the insurgents.[19][20] Their heads, also victims of an attack by savage birds,[21] were allowed to be taken down and given burial on October 14, in honor of the King's Birthday.[22]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hombres y ciudades: Antología del paisaje, de las letras y de los hombres de Colombia by Gustavo Otero Muñoz

- ^ América Española by Gabriel Porras Troconis

- ^ Cuadros de costumbres y descripciones locales de Colombia: Articulos escogidos y publicados (Page 120) by José Joaquín Borda [1]

- ^ Gobernantes de Colombia: 1810–1857. Compendio de la Historia Patria, 1492-1957 by Jorge de Mendoza Velez

- ^ Historia económica y social del Caribe colombiano (Page 164) by Nicolás del Castillo Mathieu [2]

- ^ Countries Ci-Co

- ^ Lecciones de historia de Colombia (Page 182) by Soledad Acosta de Samper

- ^ Historia de Barranquilla By Universidad Autónoma del Caribe Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Revolution, Romanticism, and the Afro-Creole Protest Tradition in Louisiana 1718-1868 (Page 47) by Caryn Cossé [3]

- ^ Constituciones de Colombia: Recopiladas y precedidas de una breve reseña historica (Page 104) by Manuel Antonio Pombo, José Joaquín Guerra [4]

- ^ Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango Archived 2007-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango Archived 2007-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ La patria boba by J. A. Vargas Jurado, José María Caballero, José Antonio de Torres y Peña [5]

- ^ Independencia de Nueva Granada y Venezuela by Francisco Antonio Encina

- ^ Manuel Rodríguez Torices by Javier López Ocampo

- ^ Vida de Don Ignacio Gutiérrez Vergara y episodios históricos de su tiempo(1806–1877) (Page 138) by Ignacio Gutiérrez Ponce [6]

- ^ Los Mártires de Cartagena by José P. Urueta

- ^ Cultura colombiana; apuntaciones sobre el movimiento intelectual de Colombia, desde la conquista hasta la época actual (Page 404) by Adolfo Dollero

- ^ De West-Indische zaken van Ferrand Whaley Hudig, 1759-1797 by Humberto Plazas Olarte, Jorge Mendoza Vélez, J. Hudig

- ^ Biblioteca de historia nacional by Academia Colombiana de Historia

- ^ Historia eclesiástica y civil de Nueva Granada: Escrita sobre documentos auténticos by José Manuel Groot [7]

- ^ Homenaje a los próceres; discursos pronunciados en la celebración del sequicentenario de la independencia nacional, 1810-1960 by Academia Colombiana de Historia

- 1788 births

- 1816 deaths

- Presidents of Colombia

- Vice presidents of Colombia

- Colombian governors

- 19th-century Colombian lawyers

- People from Cartagena, Colombia

- Colombian journalists

- Male journalists

- Executed presidents

- Colombian independence activists

- Executed Colombian people

- People executed by Colombia by hanging