Marc Bloch in World War II

Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (/blɒk/; French: [maʁk leɔpɔld bɛ̃ʒamɛ̃ blɔk]; 6 July 1886 – 16 June 1944) was a French historian. He was a founding member of the Annales School of French social history. Bloch specialised in medieval history and published widely on Medieval France. He worked at the Universities of Strasbourg (1920 to 1936), Paris (1936 to 1939), and the Montpellier (1941 to 1944).

During World War II, Bloch volunteered for service, and was a logistician during the Phoney War. Involved in the Battle of Dunkirk and spending a brief time in Britain, he unsuccessfully attempted to secure passage to the United States. Returning to France, he found his ability to work curtailed by new antisemitic regulations. However, he applied for and received one of the few permits available, allowing Jews to continue working in the French university system. He had to leave Paris, and complained that the Nazi authorities had looted his apartment and stole his books; he was also forced to relinquish his position on the editorial board of Annales. Bloch worked in Montpellier until November 1942 when Germany invaded Vichy France. Bloch then joined the French Resistance, acting predominantly as a courier and translator. In 1944, he was captured in Lyon and executed by firing squad. Several of his books were published posthumously.

Background[edit]

Marc Bloch was a French historian. He was a founding member of the Annales School of French social history. Bloch specialised in medieval history and published widely on Medieval France over the course of his career. As an academic, he worked at the University of Strasbourg (1920 to 1936), the University of Paris (1936 to 1939), and the University of Montpellier (1941 to 1944).

Born in Lyon to an Alsatian Jewish family, Bloch was raised in Paris, where his father—the classical historian Gustave Bloch—worked at Sorbonne University. Bloch was educated at various Parisian lycées and the École Normale Supérieure, and from an early age was affected by the antisemitism of the Dreyfus affair. During the First World War, he served in the French Army and fought at the First Battle of the Marne and the Somme. After the war, he was awarded his doctorate in 1918 and became a lecturer at the University of Strasbourg. There, he formed an intellectual partnership with modern historian Lucien Febvre. Together they founded the Annales School and began publishing the journal Annales d'histoire économique et sociale in 1929.

Outbreak of war[edit]

On 24 August 1939, at the age of 53,[1] Bloch was mobilised for a third time,[1] now as a fuel supply officer.[2] He was responsible for the mobilisation of the French Army's massive motorised units.[3] This involved him undertaking such a detailed assessment of the French fuel supply that he later wrote he was able to "count petrol tins and ration every drop" of fuel he obtained.[3] During the first few months of the war, called the Phoney War,[4][note 1] he was stationed in Alsace.[5] He possessed none of the eager patriotism with which he had approached the First World War. Instead, Carole Fink suggests that because Bloch felt himself to have been discriminated against, he had "begun to distance himself intellectually and emotionally from his comrades and leaders".[6] Back in Strasbourg, his main duty was evacuating civilians behind the Maginot Line.[7] Further transfers occurred, and Bloch was re-stationed to Molsheim, Saverne, and eventually to the 1st Army headquarters in Picardy,[7] where he joined the Intelligence Department, in liaison with the British.[8][note 2]

Bloch was largely bored between 1939 and May 1940 as he often had little work to do.[9] To pass the time and occupy himself, he decided to begin writing a history of France. To this end, he purchased notebooks and began to work out a structure for the work.[10] Although never completed, the pages he managed to write, "in his cold, poorly lit rooms",[11] eventually became the kernel of The Historian's Craft.[11] At one point he expected to be invited to neutral Belgium to deliver a series of lectures in Liège. These never took place, however, disappointing Bloch very much; he had planned to speak on Belgian neutrality.[11] He also turned down the opportunity to travel to Oslo as an attaché to the French Military Mission there. He was considered an excellent candidate for the position due to his fluency in Norwegian and knowledge of the country. Bloch considered it and came close to accepting; ultimately, though, it was too far from his family,[12] whom he rarely saw enough of in any case.[12][note 3] Some academics had escaped France for The New School in New York City, and the School also invited Bloch. He refused,[13] possibly because of difficulties in obtaining visas:[14] the US government would not grant visas to every member of his family.[15]

Fall of France[edit]

In May 1940, the German army outflanked the French and forced them to withdraw. Facing capture in Rennes, Bloch disguised himself in civilian clothes and lived under German occupation for a fortnight before returning to his family at their country home in Fougères.[16][17][18] He fought at the Battle of Dunkirk in May–June 1940 and was evacuated to England with the British Expeditionary Force on the requisitioned steamer MV Royal Daffodil, which he later described as taking place "under golden skies coloured by the black and fawn smoke".[19] Before the evacuation, Bloch ordered the immediate burning of fuel supplies.[16] Although he could have remained in Britain,[20] he chose to return to France the day he arrived[16] because his family was still there.[20]

Bloch felt that the French Army lacked the esprit de corps or "fervent fraternity"[21] of the French Army in the First World War.[21] He saw the French generals of 1940 as behaving as unimaginatively as Joseph Joffre had in the first war.[22] He did not, however, believe that the earlier war was an indication of how the next would progress: "no two successive wars", he wrote in 1940, "are ever the same war".[23]

To Bloch, France collapsed because her generals failed to capitalise on the best qualities humanity possessed—character and intelligence[24]—because of their own "sluggish and intractable" progress since the First World War.[4] He was horrified by the defeat which, Carole Fink has suggested, he saw as being worse, for both France and the world, than her previous defeats at Waterloo and Sedan.[25] Bloch understood the reasons for France's sudden defeat: not in the rumours of British betrayal, communist fifth columns or fascist plots, but in her failure to motorise, and perhaps more importantly, her failure to understand what motorisation meant. He understood that it was the latter that allowed the French army to become bogged down in Belgium, and this had been compounded by the French army's slow retreat. He wrote in Strange Defeat that a fast, motorised retreat might have saved the army.[26]

Two-thirds of France was occupied by Germany.[27] Bloch, one of the few elderly academics to volunteer,[17] was demobilised soon after Philippe Pétain's government signed the Armistice of 22 June 1940 forming Vichy France in the remaining southern-third of the country.[25] Bloch moved south, where in January 1941, he applied for and received[28] one of only ten exemptions to the ban on employing Jewish academics the Vichy government made.[29] This was probably due to Bloch's pre-eminence in the field of history.[14] He was allowed to work[29] at the "University of Strasbourg-in-exile",[14] the universities of Clermont-Ferrand, and Montpellier.[2] The latter, further south, was beneficial to his wife's health, which was in decline.[30] The dean of faculty at Montpellier was Augustin Fliche, an ecclesiastical historian of the Middle Ages, who, according to Weber, "made no secret of his antisemitism".[31] He disliked Bloch further for having once given him a poor review.[31] Fliche not only opposed Bloch's transfer to Montpellier but made his life uncomfortable when he was there.[32] The Vichy government was attempting to promote itself as a return to traditional French values.[33] Bloch condemned this as propaganda; the rural idyll that Vichy said it would return France to was impossible, he said, "because the idyllic, docile peasant life of the French right had never existed".[34]

Declining relationship with Febvre[edit]

It was during these bitter years of defeat, of personal recrimination, of insecurity that he wrote both the uncompromisingly condemnatory pages of Strange Defeat and the beautifully serene passages of The Historian's Craft.

The war also impacted Bloch's professional relationship with Febvre. The Nazis wanted French editorial boards to be stripped of Jews in accordance with German racial policies; Bloch advocated disobedience, while Febvre was passionate about the survival of Annales at any cost.[35] He believed that it was worth making concessions to keep the journal afloat and to keep France's intellectual life alive.[36] Bloch rejected out of hand any suggestion that he should, in his words, "fall into line".[37] Febvre also asked Bloch to resign as joint-editor of the journal. Febvre feared that Bloch's involvement, as a Jew in Nazi-occupied France, would hinder the journal's distribution.[38] Bloch, forced to accede, turned the Annales over to the sole editorship of Febvre, who then changed the journal's name to Mélanges d'Histoire Sociale. Bloch was forced to write for it under the pseudonym Marc Fougères.[35] The journal's bank account was also in Bloch's name; this too had to go.[36] Henri Hauser supported Febvre's position, and Bloch was offended when Febvre intimated that Hauser had more to lose than both of them. This was because, whereas Bloch had been allowed to retain his research position, Hauser had not. Bloch interpreted Febvre's comment as implying that Bloch was not a victim. Bloch, alluding to his ethnicity, replied that the difference between them was that, whereas he feared for his children because of their Jewishness, Febvre's children were in no more danger than any other man in the country.[37]

The Annalist historian André Burguière suggests Febvre did not really understand the position Bloch, or any French Jew, was in.[39] Already damaged by this disagreement, Bloch's and Febvre's relationship declined further when the former had been forced to leave his library and papers[14] in his Paris apartment following his move to Vichy. He had attempted to have them transported to his Creuse residence,[39] but the Nazis—-who had made their headquarters in the hotel next to Bloch's apartment[40]—-looted his rooms[40] and confiscated his library in 1942.[29] Bloch held Febvre responsible for the loss, believing he could have done more to prevent it.[29]

Bloch's mother had recently died, and his wife was ill; furthermore, although he was permitted to work and live, he faced daily harassment.[14] On 18 March 1941, Bloch made his will in Clermont-Ferrand.[41] The Polish social historian Bronisław Geremek suggests that this document hints at Bloch in some way foreseeing his death,[42] as he emphasised that nobody had the right to avoid fighting for their country.[43] In March 1942 Bloch and other French academics such as Georges Friedmann and Émile Benveniste, refused to join or condone the establishment of the Union Générale des Israelites des France by the Vichy government, a group intended to include all Jews in France, both of birth and immigration.[44]

French resistance, capture and death[edit]

In November 1942, as part of an operation known as Case Anton, the German Army crossed the demarcation line and occupied the territory previously under direct Vichy rule.[14] This was the catalyst for Bloch's decision to join the French Resistance[2] sometime between late 1942[45] and March 1943.[2] Bloch was careful not to join simply because of his ethnicity or the laws that were passed against it. As Burguière has pointed out, and Bloch would have known, taking such a position would effectively "indict all Jews who did not join".[46] Burguière has pinpointed Bloch's motive for joining the Resistance in his characteristic refusal to mince his words or play half a role.[15] Bloch had previously expressed the view that "there can be no salvation where there is not some sacrifice".[2] He sent his family away and returned to Lyon to join the underground.[14]

Despite knowing a number of francs-tireurs around Lyon, Bloch still found it difficult to join them because of his age.[46] Although the Resistance recruited heavily among university lecturers[47]—and indeed, Bloch's alma mater, the École Normale Superieur, provided it with many members[48]—he commented in exasperation to Simonne that he "didn't know it is so difficult to offer one's life".[46] The French historian and philosopher François Dosse quotes a member of the franc-tireurs active with Bloch as later describing how "that eminent professor came to put himself at our command simply and modestly".[13] Bloch used his professional and military skills on their behalf, writing propaganda for them and organising their supplies and materiel, becoming a regional organiser.[14] Bloch also joined the Mouvements Unis de la Résistance (Unified Resistance Movement, or MUR),[13] section R1,[49] and edited the underground newsletter, Cahiers Politique.[14] He went under various pseudonyms: Arpajon, Chevreuse, Narbonne.[14][note 4] Often on the move, Bloch used archival research as his excuse for travelling.[19] The journalist-turned-resistance fighter Georges Altman later told how he knew Bloch as, although originally "a man, made for the creative silence of gentle study, with a cabinet full of books" was now "running from street to street, deciphering secret letters in some Lyonaisse Resistance garret";[47] all Bloch's notes were kept in code.[40] For the first time, suggests Lyon, Bloch was forced to consider the role of the individual in history, rather than the collective; perhaps by then even realising he should have done so earlier.[51][note 5]

Capture and execution[edit]

Bloch was arrested at the Place de Pont, Lyon,[53] during a major roundup by the Vichy milice on 8 March 1944, and handed over to the Gestapo.[54] Bloch was using the pseudonym "Maurice Blanchard", and in appearance was "an ageing gentleman, rather short, grey-haired, bespectacled, neatly dressed, holding a briefcase in one hand and a cane in the other".[53] He was renting a room above a dressmaker's shop on rue des Quatre Chapeaux; the Gestapo raided the place the following day. It is possible Bloch had been denounced by a woman working in the shop.[53] In any case, they found a radio transmitter and many papers.[53] Bloch was imprisoned in Montluc prison,[13] during which time his wife died.[41] While imprisoned, he was tortured, suffering beatings and ice-baths. On occasion, his torturers broke his ribs and wrists, which led to his being returned to his cell unconscious. He eventually caught bronchopneumonia[53] and fell seriously ill. It was later claimed that he gave away no information to his interrogators, and while incarcerated taught French history to other inmates.[55]

In the meantime, the allies had invaded Normandy on 6 June 1944.[55] As a result, the Nazi regime was keen to evacuate and "liquidate their holdings"[53] in France; this meant disposing of as many prisoners as they could.[55] Between May and June 1944 the Nazi occupying forces shot around 700 prisoners in scattered locations to avoid the risk of this becoming common knowledge, thus inviting Resistance reprisals around southern France.[55] Among those killed was Bloch,[13] one of a group of 26 Resistance prisoners[55][45] picked out in Montluc[56] and driven along the Saône towards Trévoux[note 6] on the night of[55] 16 June 1944.[45] Driven to a field near Saint-Didier-de-Formans,[55] they were shot by the Gestapo in groups of four.[53] According to Lyon, Bloch spent his last moments comforting a 16-year-old beside him who was worried that the bullets might hurt.[51] Bloch fell first, reputedly shouting "Vive la France"[13] before being shot. A coup de grâce was delivered. One man managed to crawl away and later provided a detailed report of events; the bodies were discovered on 26 June.[53] For some time Bloch's death was merely a "dark rumour" until it was confirmed to Febvre.[56]

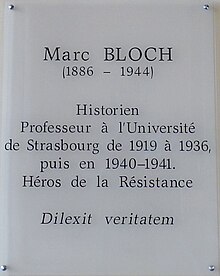

At his burial, his own words were read at the graveside. With them, Bloch proudly acknowledged his Jewish ancestry while identifying foremost as a Frenchman.[57][note 7] He described himself as "a stranger to any formal religious belief as well as any supposed racial solidarity, I have felt myself to be, quite simply French before anything else".[13] According to his instructions, no orthodox prayers were said over his grave,[41] and on it was to be carved his epitaph dilexi veritatem ("I have loved the truth").[58] In 1977, his ashes were transferred from St-Didier to Fougeres and the gravestone was inscribed as he requested.[59]

Later events[edit]

Febvre had not approved of Bloch's decision to join the Resistance, believing it to be a waste of his brain and talents,[60] although, as Davies points out, "such a fate befell many other French intellectuals".[2][note 8] Febvre continued publishing Annales, ("if in a considerably modified form" comments Beatrice Gottlieb),[60][note 9] dividing his time between his country château in the Franche-Comté[60] and working at the École Normale in Paris. This caused some outrage, and, after liberation, when classes were returning to a degree of normality, he was booed by his students at the Sorbonne.[49]

Intellectual historian Peter Burke named Bloch the leader of what he called the "French Historical Revolution",[65] and Bloch became an icon for the post-war generation of new historians.[66] Although he has been described as being, to some extent, the object of a cult in both England and France[67]—"one of the most influential historians of the twentieth century"[68] by Stirling, and "the greatest historian of modern times" by John H. Plumb[53]—this is a reputation mostly acquired postmortem.[69] Henry Loyn suggests it is also one which would have amused and amazed Bloch.[70] According to Stirling, this posed a particular problem within French historiography when Bloch effectively had martyrdom bestowed upon him after the war, leading to much of his work being overshadowed by the last months of his life.[71] This led to "indiscriminate heaps of praise under which he is now almost hopelessly buried".[45] His legacy has been further complicated by the fact that the second generation of Annalists led by Fernand Braudel has "co-opted his memory",[71][note 10] combining Bloch's academic work and Resistance involvement to create "a founding myth".[73] The aspects of his life which made Bloch easy to beatify have been summed up by Henry Loyn as "Frenchman and Jew, scholar and soldier, staff officer and Resistance worker ... articulate on the present as well as the past".[74]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Known as the drôle de guerre in French.[1]

- ^ Notwithstanding his respect for British historians, says Lyon, Bloch, like many of his compatriots, was anglophobic; he described the British soldier as naturally "a looter and a lecher: that is to say, the two vices which the French peasant finds it hard to forgive when both are satisfied to the detriment of his farmyard and his daughters",[5] and English officers as being imbued with an "old crusted Tory tradition".[5]

- ^ Carole Fink describes the meetings Bloch had with his family: "In February 1940 he made two trips to Paris—displaying signs of 'fatigue'—where he saw his wife, visited relatives and friends, and savoured the joys of civilian life: a sandwich in a café, a concert, and several good films.[12]

- ^ Bloch's pseudonyms tended to hark back to his life living on Paris' Left Bank in the 1930s. Arpajon was a train that travelled between the Boulevard St Michel and Les Halles and Chevreuse referred to Saint-Rémy-lès-Chevreuse station on the Ligne de Sceaux.[50]

- ^ Bloch questioned the lack of a collective French spirit between the wars in Strange Defeat: "we were all of us either specialists in the social sciences or workers in scientific laboratories, and maybe the very disciplines of those employments kept us, by a sort of fatalism, from embarking on individual action".[52][51]

- ^ Today this road is the route nationale 433.[53]

- ^ Davies suggests that the speech he self-described with at his funeral may be unpleasant hearing to some historians in the words' stridency and emotion. However, he also notes the necessity of remembering the context, that "they are the words of a Jew by birth writing in the darkest hour of France's history and that Bloch never confused patriotism with a narrow, exclusive nationalism".[57] In Strange Defeat, Bloch had written that the only time he had ever emphasised his ethnicity was "in the face of an antisemite".[18]

- ^ Others included Jacques Bingen, Pierre Brossolette, Jean Cavaillès and Jean Moulin. "The bourgeoisie rose to the challenge",[61] wrote Olivier Wieviorka, and "they would have continued promising careers after the war had they not decided to become engaged at the risk of their lives".[62] François Mauriac noted that he "would no longer write that only the working class has remained faithful to desecrated France. What an injustice to the host of boys from the bourgeoisie who sacrificed themselves and are still sacrificing themselves".[63]

- ^ The journal by 1946 had changed its name, of which by now it was on its fourth: it had begun as Annales d'Histoire Économique et Sociale, which it stayed as until 1939. It was then successively renamed Annales d'Histoire Sociale (1939–1942, 1945) and Mélanges d'Histoire Sociale, from 1942 to 1944, before becoming Annales. Economies, Sociétés, Civilisations from 1946.[64]

- ^ They did not do this with the intention of suppressing discussion of Bloch's ideas, wrote Karen Stirling, but "it is easy for contemporary scholars to confuse Bloch's own individualistic work as a historian with that of his structuralist successors". In other words, to apply to Bloch's views those who followed him with, in some cases, rather different interpretations of those views.[72]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Fink 1998, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g Davies 1967, p. 268.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 45.

- ^ a b Stirling 2007, p. 533.

- ^ a b c Lyon 1985, p. 188.

- ^ Fink 1998, p. 41.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Fink 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Loyn 1999, p. 164.

- ^ Fink 1998, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Fink 1998, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Fink 1998, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dosse 1994, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fink 1995, p. 208.

- ^ a b Burguière 2009, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Fink 1995, p. 207.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 42.

- ^ a b Bloch 1949, p. 23.

- ^ a b Weber 1991, p. 256.

- ^ a b Kaye 2001, p. 97.

- ^ a b Lyon 1985, p. 184.

- ^ Lyon 1985, p. 187.

- ^ Lyon 1985, p. 189.

- ^ Davies 1967, p. 281.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 39.

- ^ Chirot 1984, p. 42.

- ^ Hughes-Warrington 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Birnbaum 2007, p. 251 n.92.

- ^ a b c d Epstein 1993, p. 276.

- ^ Hughes 2002, p. 127.

- ^ a b Weber 1991, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Weber 1991, p. 254.

- ^ Levine 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Chirot 1984, p. 43.

- ^ a b Dosse 1994, p. 43.

- ^ a b Burguière 2009, p. 43.

- ^ a b Burguière 2009, p. 44.

- ^ Stirling 2007, p. 530.

- ^ a b Burguière 2009, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Weber 1991, p. 249.

- ^ a b c Loyn 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Geremek 1986, p. 1103.

- ^ Geremek 1986, p. 1105.

- ^ Birnbaum 2007, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d Stirling 2007, p. 531.

- ^ a b c Burguière 2009, p. 47.

- ^ a b Geremek 1986, p. 1104.

- ^ Smith 1982, p. 268.

- ^ a b Wieviorka 2016, p. 102.

- ^ Weber 1991, p. 245.

- ^ a b c Lyon 1985, p. 186.

- ^ Bloch 1980, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Weber 1991, p. 244.

- ^ Freire 2015, p. 170 n.60.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fink 1995, p. 209.

- ^ a b Burguière 2009, p. 39.

- ^ a b Davies 1967, p. 282.

- ^ Loyn 1999, p. 174.

- ^ Weber 1991, p. 258.

- ^ a b c Gottlieb 1982, p. xv.

- ^ Wieviorka 2016, p. 390.

- ^ Wieviorka 2016, p. 103.

- ^ Wieviorka 2016, p. 389.

- ^ Burke 1990, p. 116 n.2.

- ^ Burke 1990, p. 7.

- ^ Sreedharan 2004, p. 259.

- ^ Davies 1967, p. 265.

- ^ Stirling 2007, p. 525.

- ^ Epstein 1993, p. 273.

- ^ Loyn 1999, p. 165.

- ^ a b Stirling 2007, p. 526.

- ^ Stirling 2007, p. 536 n.3.

- ^ Epstein 1993, p. 282.

- ^ Loyn 1999, pp. 162–163.

Bibliography[edit]

- Birnbaum, P. (2007). "The Absence of an Encounter: Sociology And Jewish Studies". In Gotzmann, A.; Wiese, C. (eds.). Modern Judaism and Historical Consciousness: Identities, Encounters, Perspectives. Louvain: Brill. pp. 224–273. ISBN 978-9-04742-004-0.

- Bloch, M. (1949). Strange Defeat: A Statement of Evidence Written in 1940. Translated by Hopkins, G. London: Cumberlege. OCLC 845097475.

- Bloch, M. (1980). Fink C. (ed.). Memoirs of War, 1914–15. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52137-980-9.

- Burguière, A. (2009). Todd J. M. (ed.). The Annales School: An Intellectual History. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-80144-665-8.

- Burke, P. (1990). The French Historical Revolution: The Annales School, 1929–89. Oxford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-80471-837-0.

- Chirot, D. (1984). "Social and Historical Landscapes of Marc Bloch". In Skocpol T. (ed.). Vision and Method in Historical Sociology. Conference on Methods of Historical Social Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–46. ISBN 978-0-52129-724-0.

- Davies, R. R. (1967). "Marc Bloch". History. 52: 265–282. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229x.1967.tb01201.x. OCLC 466923053.

- Dosse, F. (1994). New History in France: The Triumph of the Annales. Translated by Conroy P. V. (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-25206-373-2.

- Epstein, S. R. (1993). "Marc Bloch: The Identity of a Historian". Journal of Medieval History. 19: 273–283. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(93)90017-7. OCLC 1010358128.

- Fink, C. (1995). "Marc Bloch (1886–1944)". In Damico H. Zavadil J. B. (ed.). Medieval Scholarship: Biographical Studies on the Formation of a Discipline: History. London: Routledge. pp. 205–218. ISBN 978-1-31794-335-8.

- Fink, C. (1998). "Marc Bloc and the Drôle de Guerre: Prelude to the "Strange Defeat"". In Blatt, J. (ed.). The French Defeat of 1940: Reassessments. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 39–53. ISBN 978-0-85745-717-2.

- Freire, O. (2015). The Quantum Dissidents: Rebuilding the Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (1950–1990). London: Springer. ISBN 978-3-66244-662-1.

- Geremek, B. (1986). "Marc Bloch, Historien et Résistant". Annales: Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations. 41: 1091–1105. doi:10.3406/ahess.1986.283334. OCLC 610582925.

- Gottlieb, B. (1982). "Introduction". The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century: The Religion of Rabelais. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. pp. xi–xxxii. ISBN 978-0-67470-826-6.

- Hughes, H. S. (2002). The Obstructed Path: French Social Thought in the Years of Desperation 1930–1960. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-35147-820-5.

- Hughes-Warrington, M. (2015). Fifty Key Thinkers on History (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13448-253-5.

- Kaye, H. J. (2001). Are We Good Citizens? Affairs Political, Literary, and academic. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 978-0-80774-019-4.

- Levine, A. J. M. (2010). Framing the Nation: Documentary Film in Interwar France. New York, NY: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-44113-963-4.

- Loyn, H. (1999). "Marc Bloch". In Clark, C. (ed.). Febvre, Bloch and other Annales Historians. The Annales School. Vol. IV. London: Routledge. pp. 162–176. ISBN 978-0-41520-237-4.

- Lyon, B. (1985). "Marc Bloch: Did He Repudiate Annales History?". Journal of Medieval History. 11: 181–192. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(85)90023-5. OCLC 1010358128.

- Smith, R. J. (1982). The École Normale Superieure and the Third Republic. New York, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-541-6.

- Sreedharan, E. (2004). A Textbook of Historiography, 500 B.C. to A.D. 2000. London: Longman. ISBN 978-8-12502-657-0.

- Stirling, K. (2007). "Rereading Marc Bloch: The Life and Works of a Visionary Modernist". History Compass. 5: 525–538. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00409.x. OCLC 423737359.

- Weber, E. (1991). My France: Politics, Culture, Myth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67459-576-7.

- Wieviorka, O. (2016). The French Resistance. Translated by Todd, J. M. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67473-122-6.

- 1886 births

- 1944 deaths

- 20th-century French historians

- Deaths by firearm in France

- Executed people from Rhône-Alpes

- French Army officers

- French Army personnel of World War II

- French civilians killed in World War II

- French military personnel of World War I

- French people executed by Nazi Germany

- French Resistance members

- Jews in the French resistance

- People executed by Nazi Germany by firing squad

- Resistance members killed by Nazi Germany

- Writers from Lyon