Marcelino Ulibarri Eguilaz

Marcelino Ulibarri Eguilaz | |

|---|---|

| Born | Marcelino Ulibarri Eguilaz 1880 Muez, Spain |

| Died | 1951 Tafalla, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | corporate manager |

| Known for | civil servant, politician |

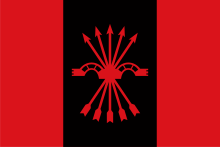

| Political party | Carlism, FET |

Marcelino de Ulibarri y Eguilaz (1880–1951) was a Spanish politician and civil servant. He is best known as head of repressive institutions of early Francoism: Delegación Nacional de Asuntos Especiales (1937–1938), Delegación del Estado para Recuperación de Documentos (1938–1944) and Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo (1940–1941). Politically he was a longtime supporter of the Carlist cause. He briefly presided over the regional Aragón party branch (1933) and was member of the Navarrese regional executive (1936–1937), but during the Civil War he assumed a Francoist stand. During 4 terms he was member of the Falange Española Tradicionalista executive, Consejo Nacional (1939–1951), and during 3 terms he served in the Francoist Cortes (1943–1951).

Family and youth[edit]

The Basque family of Ulibarri (spelled also Ullibarri, Ulíbarri or Uribarri)[1] was first recorded in the Medieval era; across the centuries it got very branched, also in America, and produced a number of recognized personalities.[2] Marcelino's forefathers formed part of the Navarrese hidalguia; his most distant ancestor identified was the great-grandfather Domingo, recorded in the late 18th century.[3] His son and Marcelino's grandfather, Juan Ciriaco de Ulibarri Mélida (died 1883),[4] was noted as "rico propietario" in Muez, a hamlet in the central Navarrese zone known as Tierra Estella.[5] His son and the father of Marcelino, Ignacio de Ulibarri Hita[6] (died after 1916),[7] served as the mayor of Muez in the mid-1880s.[8] In sources he was also named "rico propietario de Muez"[9] and mentioned in relation to a multi-faceted agricultural business,[10] though in 1915 the press referred to him also as "comerciante".[11] The Ulibarri house in Muez, named "la casa de la Parra",[12] was considered to have been "la principal del pueblo".[13]

At unspecified time, though probably in the 1870s, Ulibarri Hita married Hilaria Eguiláz Pérez[14] (died after 1909),[15] a girl from the nearby village of Guirguillano.[16] The couple had at least 7 children, almost all boys,[17] with Marcelino born as the third oldest son.[18] It is not clear what language was spoken at home, as at the time Muez was at the borders of the Basque-speaking zone,[19] yet it is known that all siblings were raised in very pious way.[20] None of the sources consulted provides information on education of the young Marcelino, though some later episodes suggest he frequented a Piarist college, most likely in Pamplona.[21] It is neither clear whether and if yes when and where he pursued an academic career, especially given very complex specialized, administrative, and bureaucratic tasks he would perform in the future; some press notes from his early 20s mention him in relation to Zaragoza[22] and some suggest a juridical background.[23]

In historiography Ulibarri is referred to as a somewhat mysterious individual with merely few details from his biography known;[24] this refers also to beginnings of his professional career, which remain entirely unclear except that they were related to Zaragoza.[25] It is known he was somehow associated with agriculture,[26] though as an official or a finance clerk rather than as a landholder.[27] At some stage, yet no later than in the early 1920s, he joined La Equitativa,[28] a Spanish subsidiary of the US insurance company, and worked in its Zaragoza branch, growing to mid-range management positions in the mid-1920s.[29] In 1908 Ulibarri married Petra Castiella Pérez[30] (died 1964),[31] a girl from Tafalla;[32] she was daughter to Domingo Castiella Cuadrado[33] from a locally distinguished family of the Navarrese Ribera.[34] The couple settled in Zaragoza,[35] though at later stages they lived in Tafalla, Salamanca[36] and again in Tafalla; they had no children.[37] Ulibarri's best known relative is his nephew, Pedro Ruiz de Ulibarri, who until the early 1980s held various important posts in Spanish archival structures, including Sección Guerra Civil del Archivo Histórico Nacional.[38]

Early political engagements[edit]

The Ulibarris are described as "una familia ya acendradamente carlista en la primera guerra", i.e. Carlist since the First Carlist War in the 1830s.[39] In the 1860s they subscribed to various Traditionalist initiatives.[40] During the Third Carlist War in the 1870s the family house in Muez hosted the claimant Carlos VII and his wife, who spent few nights there in wake of the Abárzuza battle; Marcelino's mother would later for decades keep recollecting this episode.[41] First information on Marcelino's engagements are related to his early 20s; in 1904 he presided over a Carlist committee organizing a local Traditionalist event in Zaragoza,[42] and in 1905 he was within a group which set up Juventud Carlista in the Aragonese capital.[43] By the end of the decade Ulibarri was already in touch with major local personalities of the party. In 1907 he took part in electoral campaign of the Navarrese heavyweight Conde Rodezno, who competed for the Cortes ticket from Aoiz.[44]

In the 1910s Ulibarri emerged among publicly recognizable politicians of the Aragonese branch of Carlism. In 1910 he represented jefé regional, Pascual Comín, in the local Junta de Censo, apparently when protesting alleged electoral irregularities;[45] the same year he was among organizers[46] and major speakers[47] during rallies against secular schools, called by right-wing Catholic groupings. He started to appear also beyond Aragón, e.g. during a 1911 banquet in Madrid, intended to honor Carlist and Integrist deputies to the Cortes.[48] Though in his early 30s, at the time he was still related to Juventud Carlista, e.g. in 1912 he featured in its Comision Organizadora during preparations to a local rally.[49] In the early 1910s his formal role was this of secretario of Junta Regional, still presided by Comín.[50]

In the mid-1910s Carlism was increasingly plagued by a conflict between the key Traditionalist theorist, Juan Vázquez de Mella, and the claimant Don Jaime. Ulibarri is not listed among the protagonists.[51] When in 1919 the controversy escalated to full-scale showdown and produced secession of the Mellistas, Ulibarri remained loyal to his king. However, he assumed somewhat challenging stance when in 1920 he co-signed an open letter to Don Jaime. In polite yet bold terms the signatories demanded destitution of the key party Francophone Francisco Melgar, appointment of new editor of the Carlist mouthpiece El Correo Español, and setting up a collegial nationwide party executive.[52] By the end of the decade Ulibarri's position in Zaragoza was already firm, also beyond politics. In the press he was noted as "inspector" and acknowledged on societè columns.[53] In 1918 he took part in a meeting organized by Diputación Provincial, inspired by Junta de la Defensa del Agricultor and intended to tackle agricultural problems; it is not clear what institution he represented.[54]

Dictatorship and Republic[edit]

In the 1920s Ulibarri was barely noted as engaged in political or meta-political activities, especially that in 1923 dictatorship of Primo de Rivera effectively suspended activity of political parties. During the decade Ulibarri was recorded mostly as taking part in various Catholic initiatives, e.g. in 1923 he co-organized a local Zaragoza campaign against blasphemy,[55] and in 1929 he was active in the male Christian brotherhood of Caballeros del Pilar;[56] both his family[57] and scholars claimed later that he has always been very religious.[58] His activity in Federación Católico-Social Navarra was more about economy than religion, as in wake of the overproduction crisis he represented the Navarrese agricultural syndicate in a joint inter-provincial "Comité de defensa de los intereses trigueros".[59] Numerous authors claim that in the late 1920s Ulibarri befriended Francisco Franco, a young general who in 1928 became head of the newly established Academia General Militar in Zaragoza. There is never a source provided to support these claims[60] and it is not clear in what circumstances a nationwide known general might have interfaced with a local Carlist.

According to some sources already in 1931 Ulibarri ascended to “jefe de Comunión Tradicionalista en Aragón”, the position he reportedly held until 1933.[61] However, in 1932 in the press he was noted merely as “señor”[62] and a CT organigram from early 1932 does not list him as a leader either on regional or provincial level; the regional Aragón organisation was led by Carlos Ram de Víu Aréval and the provincial Zaragoza one by Manuel de Ardid.[63] It is only in 1933 that Ulibarri started to appear as “delegado regional”[64] and represent Junta Regional in Spanish party executive,[65] though he did not feature among nationwide important Carlist protagonists.[66] However, his tenure as the regional Aragon leader was rather brief. In March 1934 he was noted merely as treasurer of Junta Regional de Aragón, presided by Jesús Comín,[67] and in 1935 the press noted him as “ex jefe regional”;[68] he would not assume any role in either Aragonese or Navarrese Carlist structures until outbreak of the civil war.

Since early months of the Second Republic Ulibarri took park in labors intended to unite local right-wing opposition; in December 1931 he was noted as co-signatory of a manifesto, which launched Unión de Derechas; this provincial Zaragoza alliance was supposed to group the Carlists from Comunión Tradicionalista and politicians from Acción Nacional.[69] In 1932 he was present during a meeting in Centro de Acción, with Gil-Robles as the key speaker,[70] and prior to 1933 elections he co-signed an electoral manifesto of the local Unión de Derechas.[71] In the mid-1930s he co-operated closely with Ramón Serrano Suñer,[72] not only supporting his CEDA candidacy from Zaragoza during the 1936 elections, but reportedly also as a person who inspired Serrano to run for the Cortes.[73] For reasons which are not clear, having spent 25 years in Zaragoza in late 1934 Ulibarri moved to Tafalla,[74] even though seasonally he used to live in the Aragonese capital.[75]

Civil War, early months[edit]

Ulibarri was involved in conspiracy talks leading to Carlist taking part in the July Coup; the national leader Manuel Fal Conde counted him among the faction who did not believe in a standalone insurrection, but who advocated a joint Carlist-military action instead.[76] Some sources credit his effort as "responsable carlista de transportes", which enabled "participación masiva" of Navarrese volunteers in the rising.[77] Others find it surprising that as a person who had spent 25 years beyond Navarre, Ulibarri entered Junta Central Carlista de Guerra de Navarra (JCCGN), a wartime Carlist regional executive.[78] In the Junta he represented the merindad of Tafalla[79] and formed part of Delegación de Intendencia y Transporte of JCCGN.[80] Though in some sources Ulibarri is referred to as "militar navarro de tendencia carlista"[81] "militar carlí",[82] "requeté Marcelino Ulibarri",[83] "Navarre Carlist officer Marcelino Ulibarri",[84] or "a Carlist professional soldier"[85] there is no evidence he has ever served either in military or paramilitary structures.[86]

There is almost no information on Ulibarri's JCCGN engagements during the remainder of 1936, except that in December together with few Carlist Navarrese heavyweights he visited Franco in his headquarters in Salamanca. One purpose was to discuss a prisoner exchange, engineered by the Navarrese which Franco disapproved of.[87] Another was the question of the Carlist leader Manuel Fal Conde having been exiled on trumped-up charges of disloyalty. During the meeting Ulibarri tried to arrange Fal's return to Nationalist zone, though he also criticised Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra, the central Carlist wartime executive, for not having co-ordinated its initiatives with the military.[88] In daily dealings he also advocated close alignment with the army; in January 1937, when discussing would-be revenge measures in response to Republican killings of Traditionalist pundits in Bilbao prisons, he supported retaliation but in framework of official military justice, as "one can not ignore law when willing to do justice"[89] and in order not to "follow the rules implemented by the reds".[90]

When Carlists faced the threat of would-be forced amalgamation into a new state party, Ulibarri was in favor of complying with the military dictate.[91] In late March he was within a delegation sent by JCCGN to Saint-Jean-de-Luz to convince the regent-claimant, Don Javier.[92] In Franco's headquarters he was viewed as one of the tractable Carlists. In early April he was among 4 leaders[93] invited to Salamanca, where generalísimo briefed them on terms of the forthcoming unification.[94] When discussing personalities with Rodezno, Franco suggested that Ulibarri be among 3 Carlists to enter the 10-member executive of Falange Española Tradicionalista, just about to be launched. However, Rodezno responded that too many Navarros in Junta Política would not make a good impression, and eventually Ulibarri was replaced by Carlists from La Rioja and from Madrid.[95] He later declared himself a fervent supporter of the unification,[96] yet some scholars claim that Ulibarri was not on good terms with the Falangist sector of the regime.[97]

DNAE and SRD[edit]

In April 1937 Nicolás Franco, head of Secretaría General del Jefe de Estado, set up Oficina de Investigación y Propaganda Anti-Comunista (OIPA); its principal task was to comb newly seized territories for documents produced by Communist structures.[98] Some authors claim that it was Ulibarri who “planted in the mind of his powerful friend” (i.e. Franco) the idea of creating an investigative body, which materialized as OIPA,[99] and some even maintain that he was heading the Office,[100] but other scholars do not mention him as related.[101] Historiographic works do not agree on further fate of the institution, though from scholarly narratives it appears that it was soon either merged with or amalgamated into other similar bodies.[102]

In May 1937[103] Franco's Secretaría Particular[104] set up Delegación Nacional de Asuntos Especiales (DNAE),[105] affiliated to Secretaría General;[106] its task was to recover and collect all documents related to masonic activity, especially on newly seized territories. Ulibarri as Delegado Nacional was nominated head of the institution.[107] Some sources claim that he was also nominated director of another investigative body, Servicio de Recuperación de Documentos (SRD),[108] set up in June 1937[109] as branch of Cuartel General;[110] this one was entrusted with similar task, but related to Communist activity. Other sources do not mention such an institution.[111]

Many scholars discuss Ulibarri's nomination against the background of his alleged friendship with Franco, reportedly dating back to the 1928–1931 years in Zaragoza, and their common anti-masonic obsession.[112] Others prefer rather to underline his close familiarity with Serrano Suñer, who has just emerged as Franco's key advisor and architect of the new regime; reportedly he was responsible for Ulibarri's nomination.[113] Some mention Ulibarri's alleged propaganda role in JCCGN as a key motive behind the appointment.[114] His manifested distance towards the intransigent Carlist stand of Fal Conde has also gained him trust in Franco's headquarters.[115] None of the sources consulted discusses Ulibarri's record in La Equitativa, which has provided him with experience and competence in terms of investigation, document circulation and database management.

It is not clear how numerous the DNAE staff was; the institution was based in what used to be Seminario Mayor in Salamanca.[116] Its first major task was related to the Nationalist conquest of Biscay in June 1937,[117] though it is not clear whether Ulibarri personally travelled to Bilbao. It is known that as part of his duties he was involved in compiling a list of Catholic priests, engaged in Basque Nationalist propaganda; reportedly 6 of them have later been persecuted.[118] As the Nationalist offensive in the northern enclave progressed,[119] in August Ulibarri and his men travelled to freshly seized Santander to comb out Republican documentation left behind.[120] Documents were packed and transported to Salamanca, where an increasingly large makeshift archive started to emerge in the DNAE premises.[121]

DERD[edit]

In April 1938 the provisional ministry of interior, headed by Serrano Suñer, issued a decree which established Delegación del Estado para Recuperación de Documentos (DERD).[122] Affiliated to Ministerio de la Gobernación[123] though partially supervised by the military,[124] it was to recover, collect, catalogue and store all official documents produced by the Republicans, not only these related to freemasonry or Communist propaganda. Most scholars claim that DERD replaced all previously existing similar bodies, including DNAE[125] and SRD[126] (some claim also OIPA),[127] which were merged within the new structure.[128] In May Ulibarri as Delegado de Estado was nominated the head of DERD,[129] to be moved from Seminario Mayor to Colegio San Ambrosio in Salamanca.[130]

Following Nationalist takeover of Castellón in June 1938 Ulibarri did not go to the Mediterranean coast himself, but nominated his deputies to run the search for documents.[131] At the time he was busy building the team[132] and working out related admin and logistics routine.[133] He was also overwhelmed by massive growth of the archive and tried to arrange new premises as its permanent location,[134] in Salamanca or elsewhere; he was increasingly anxious about would-be fire or sabotage.[135] In December 1938 he claimed having collected 5m documents,[136] and in a letter to Franco declared 15.000 individual files on freemasons on the shelves.[137] In January and February 1939 Ulibarri led a team of 80 DERD staff who combed Barcelona.[138] They later returned to Salamanca with 3,500 bags,[139] 160 tons of paper and 1.800 documentary units,[140] though in April he had to move to Madrid to organize similar search in the capital.[141] The experience rendered him "a genuine expert in purging the offices".[142] Throughout the process he was frequently involved in conflict with other services, e.g. the Falange intelligence unit, DGS,[143] and SIPM,[144] apart from clashes with Juan Tusquets, who was reluctant to hand over documentation he had earlier collected.[145] Ulibarri's relations with other institutions remained tense;[146] he was very restrictive as to sharing the documents,[147] even though was forced to transfer some collections elsewhere.[148]

After the war Ulibarri tried to move the archive to El Escorial under the changed name of "Archivos Documentales de la Cruzada de España", the efforts which proved unsuccessful; he would attempt to find a new site for the ever-growing archive[149] until 1941, with a few various locations suggested.[150] He also recommended that DERD engages in education – which in few years produced opening of an internal Museo de la Masonería[151] - and restructuring the institution, with one of its sections assuming a juridical role.[152] Another of his proposals featured issuing "certificado de antecedentes", a document summarizing previous activity of given individual.[153] However, in the early 1940s Ulibarri was decreasingly interested in DERD. Since 1942 frequently absent on sick leave in Tafalla,[154] the same year he formally asked to be released.[155] His request was granted in 1944,[156] when DERD was transformed into Delegación Nacional de Servicios Documentales (DNSD),[157] the body operational until 1977.[158] When he was leaving, the institution held 3m individual files.[159]

TERMC[edit]

Already in 1939 Ulibarri suggested in his memorandum that DERD as a restructured institution should assume juridical functions.[160] It is not clear whether his proposals contributed to further developments, of which the first step was Ley para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo, published in March 1940.[161] It declared membership in masonic or Communist organizations a crime, and in one of its paragraphs envisioned setup of a "tribunal especial", to deal with such offences in case of civilians.[162] The tribunal in question materialized in June 1940 as Tribunal Especial para la Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo (TERMC), one of 25 special tribunals set up by the early Francoist regime. Composed of 6 members, it was to be presided by Ulibarri.[163] Like in case of other institutions, scholars speculate that the appointment might have been related to Ulibarri's friendship either with Franco or with Serrano and his zealous anti-masonic and anti-Communist views, apart from his successful record in DERD.[164]

During the second half of 1940 Ulibarri was busy working on both legal groundwork and internal rules of the Tribunal. In case of the former he turned to academic experts in penal law like Isaías Sánchez Tejerina from the University of Salamanca, asking them for advice as to legal framework of the persecution.[165] In case of the latter he tried to devise the modus operandi himself, guided by the principle that the anti-masonic and anti-Communist justice should be dispensed fast and with few formalities. He underlined that "excesiva preocupación legalista" should be avoided; he also opted for non-public proceedings performed in absence of the person investigated and with no assistance on part of professionals in law.[166] Like in case of other special tribunals, there was no appeal envisioned.

Before the Tribunal had its first sitting, in early 1941 Ulibarri resigned from the presidency;[167] reasons are not known. A new decree, issued in March 1941, nominated members of the tribunal anew; the presidency went to general Andres Saliquet, and Ulibarri was merely one of 6 members.[168] TERMC started to operate in April 1941,[169] and its first sentences were delivered in September against numerous Republican personalities, all of them on exile, Diego Martínez Barrio having been the first one.[170] Later the Tribunal sentenced also defunct politicians, like Andreu Nín.[171] Ulibarri was not within the Tribunal jury which delivered first sentences, yet some scholars claim that he "was in charge of drafting the sentences during his first year".[172] TERMC launched 64.000 investigations during 25 years of its existence,[173] but t is not clear in how many proceedings Ulibarri did take part before in 1942 he quoted health reasons and asked to be released.[174] It is not known when his request was granted. Last known case of Ulibarri forming part of the tribunal is dated 1945 and refers to Elías Ahúja Andría, who was declared not guilty.[175]

Dignitary[edit]

Though in April 1937 Franco intended to nominate Ulibarri to Junta Política of Falange Española Tradicionalista and abandoned the idea only upon the advice of Rodezno, in October 1937 he neither nominated Ulibarri to Consejo Nacional, another and somewhat less empowered executive body of FET. Its 2-year-term was about to expire in the autumn of 1939 and in September Franco nominated members of the II. Consejo. This time Ulibarri was included, positioned as the last one on the list of 90 nominees.[176] In the mammoth body which provided its members with little decision-making power, but mattered in terms of prestige and position within the regime, he featured as one of 14 Carlists.[177] In November 1942 the III. Consejo Nacional was appointed; this time Ulibarri was listed as 59th on the list of 95 nominees,[178] 12 of them Carlists.[179]

In early 1943 the Francoist regime underwent one of its final formal re-definitions when Cortes Españolas, a quasi-parliament, has been established; some view it as a measure of fascization of the regime, others see it rather as a first step towards de-fascization.[180] By default all members of the FET Consejo Nacional became so-called procuradores in the chamber, which referred also to Ulibarri.[181] This sequence of events was repeated 3 times. In May 1946 Franco appointed Ulibarri to IV. FET Consejo Nacional (on position 24 out of 50),[182] which the same month translated to his mandate into the II. Cortes.[183] In May 1949 he was appointed to the V. FET Consejo Nacional (on position 23 out of 49),[184] which the same month was acknowledged by a mandate to the III. Cortes;[185] Ulibarri held it until his death.

Having resigned his positions in DERD and TERMC Ulibarri had no real power, be it in political or other terms, even though the press reported him as engaged in various legislative works[186] and some sources suggest some influence on personal appointments in Francoist administration, e.g. in 1940–1941 in Valencia.[187] However, seats in Consejo Nacional and Cortes ensured his position within the titular elite of the regime. In 1944 he was awarded 2 prestigious honors, Orden de Cisneros[188] and Gran Cruz de la Orden del Mérito Civil.[189] He terminated any links to mainstream Carlism, either on the regional Navarrese[190] or the national level,[191] and though featuring among best-known so-called carlo-franquistas, he also counted among “conocidos disidentes tradicionalistas”.[192] In his final years in the late 1940s and early 1950s and reportedly due to health reasons he withdrew to privacy; his death was noted in the press with moderate[193] and not necessarily accurate[194] acknowledgements.

In historiography[edit]

Until the mid-1930s and during most of his lifetime Ulibarri remained a private figure, apart from local Navarrese and Aragonese Carlist circles mentioned only in societé column of Pamplona and Zaragoza newspapers. His rather specific 1937–1942 role first in DNAE and then in DERD was not subject to media focus.[195] Neither his brief term in TERMC received more than perfunctory media coverage, and in the 1940s his name appeared in papers rather in long-winded lists of Consejo Nacional appointees. His death has passed almost unacknowledged, and afterwards his name has gone into almost complete oblivion. If appearing in history books, e.g. in Joaquín Arrarás’ work on Republic and war (1968)[196] or in Eduardo Alvárez Puga’s history of Falange (1969)[197] he appeared very briefly in relation to Carlism and Unification.

Things took a sharp turn after the fall of the regime. Mushrooming works on Francoist repression, terror, its anti-democratic character, its victims, its oppressive structures etc. started to mention Ulibarri, and until today he is present in scores of books, usually noted only en passant.[198] He is listed among personalities responsible for buildup of the criminal Francoist system and his work is dubbed "key element in the information system underpinning the New State’s judicial structure".[199] If dedicated few sentences, he is presented as a somewhat psychopathic personality, marked by numerous obsessions: about Freemasonry ("obsessive anti-Freemasonry that Ulibarri shared with Franco"),[200] about secrecy ("el secretismo y la seguridad, que se requería para trabajar en el mismo, en periodo de guerra, y que, a Marcelino de Ulibarri, tanto obsesionaba")[201] or about sabotage ("siempre lo obsesionó la idea que ‘su’ Archivo sufriera algún acto de sabotaje, en forma de incendio provocado").[202] Some suggest he was managing sort of a secular Francoist Inquisition.[203]

So far no author has attempted to scrutinize Ulibarri's work in terms of professional competence as the manager of DNAE and DERD, be it when it comes to archival tasks (e.g. database architecture, cataloguing systems, document storage, data proliferation patterns) or to the investigative dimension (documentation recovery, data analysis, research methodologies).[204] In some works he is referred to as "un personaje misterioso y con una biografía desconocida"[205] and presented as sort of grey eminence, counted among "personalidades más grises y desconocidas".[206] His 25-year spell in Zaragoza remains barely known, especially in terms of his professional engagements.[207] Numerous studies replicate information which is either erroneous (e.g. about his alleged career of a professional military man)[208] or not sourced (e.g. about his alleged friendship with Franco during the Zaragoza days of 1928–1931). There are two works, both PhD dissertations, where he was paid more attention: the one on DERD archive mentioned him 118 times[209] and in the one on anti-masonic measures against females he was dedicated a separate sub-chapter.[210]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Ullibarri, Ulibarri entry, [in:] Blasonari. Genealogia y Heráldica service, available here. Also in case of Marcelino his surname might have appeared in different spelling versions, for "Ulíbarri Eguilaz" see e.g. Avisador Numantino 13.09.39, available here, for "Ullibarri Eguilaz" see e.g. El Progreso 13.09.39, available here

- ^ e.g. Juan Ruiz de Ulibarri was a copista who in the late 16th century copied Poema del Cid, Juan Ruiz de Ulibarri y Leyva entry, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here

- ^ Domingo de Ulibarri in 1776 married Francisca Mélida, Domingo de Ulibarri entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ he married Florencia Hita y Pérez de Lizasoain, Florencia Hita y Perez de Lizasoain entry, [in:] FamilySearch service, available here, also Marcelino de Ulibarri Eguilaz entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here. Florencia died 1869, La Esperanza 13.02.69, available here

- ^ El Eco de Navarra 15.05.13, available here

- ^ Marcelino de Ulibarri Eguilaz entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ he was last mentioned in the press in 1916, Diario de Navarra 16.09.16

- ^ Lau-buru 20.08.85, available here

- ^ Diario de Navarra 22.05.08, p. 4

- ^ El Eco de Navarra 23.09.97, available here

- ^ Diario de Navarra 05.09.15, p. 3

- ^ María Isabel Ruiz de Ulíbarri, [in:] Fundación Ignacio Larramendi service, available here

- ^ “la casa de Ulíbarri, la principal del pueblo después del palacio de Guendulain, pero la primera en rigor por hallarse el palacio derruido”. Pedro Madrazo y Kuntz, España. Sus monumentos y artes – su naturaleza é historia, Barcelona 1886, pp. 218-219

- ^ Marcelino de Ulibarri Eguilaz entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here, see also Hilaria Eguilaz entry, [in:] FamilySearch service, available here

- ^ in 1909 she was listed as signatory of an open letter, protesting alleged anti-religious policy, Diario de Navarra 30.09.09

- ^ in 1965 she was listed as based in Guirguillano, El Pensamiento Español 08.09.65, available here

- ^ the only daughter was Isabel (1884–1971). For her birth date see Ysabel Aquilina Ulibarri Eguilaz entry, [in:] FamilySearch service, available here, for death date see Diario de Navarra 31.07.71

- ^ named Demetrio, Isabel, Jose, Marcelino, Eusebio, Flaviano, and Miguel, Marcelino de Ulibarri Eguilaz entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ compare the map of Basque dialects, available [[:es:Louis Lucien Bonaparte#/media/Archivo:Bonaparte euskalki mapa.jpg|]]

- ^ see accounts of Marcelino’s niece, who was referring to his sister and the entire family, María Isabel Ruiz de Ulíbarri, [in:] Fundación Ignacio Larramendi service, available here; the "abuela" mentioned in the account is Marcelino’s mother, Hilaria Eguilaz. For open letters she signed (or was listed as signatory, since at the time she was either a child or a teenager) in support of religious initiatives, see El Pensamiento Español 08.09.65, available here

- ^ one work mentions his "trato estrecho con los escolapios", Juan Iturralde, La guerra de Franco, Madrid 1978, p. 387

- ^ Diario de Avisos de Zaragoza 03.11.04, available here

- ^ in 1910 he represented Pascual Comín during the sitting of Junta de Censo in Zaragoza; he protested alleged electoral irregularities, Congreso de los Diputados. Diario de las sesiones, Madrid 1910, p. 17

- ^ “un personaje misterioso y con una biografía desconocida”, R. J. Campo, Un carlista gestó en Zaragoza el archivo de la Guerra Civil, [in:] Heraldo de Aragón 13.02.05; he is counted among “personalidades más grises y desconocidas”, Gutmaro Gómez Bravo, Jorge Marco Carretero, La obra del miedo. Violencia y sociedad en la España franquista 1936–1950, Barcelona 2011, ISBN 9788499420912, p. 159

- ^ 1906 “ha regresado á Zaragoza despues de pasar unos dias en Pamplona”, Diario de Navarra 14.12.06; in 1909 he travelled back to Zaragoza, La Correspondencia de España 14.05.09, available here

- ^ in 1924 he represented Federación Católico-Social Navarra, as one of 2 Navarrese rural sindicates, in a Zaragoza meeting of producers from Aragón, Navarra, Rioja and Lérida, united in Comité de Defensa de los intereses trigueros; it was organised in wake of overproduction and falling prices, Emilio Majuelo Gil, Angel Pascual Bonis, Del catolicismo agrario al cooperativismo empresarial. Setenta y cinco años de la Federación de Cooperativas navarras, 1910–1985, Madrid 1991, ISBN 8474798949, p. 156

- ^ in 1916 he was referred to in the press as “inspector”, La Crónica. Diario Independiente 30.11.16, p. 3. In 1918 he took part in a meeting in Aragonese Diputación, organized by Junta de la Defensa del Agricultor and related to sugarbeets, Heraldo de Aragon 04.03.18, available here. In 1918 an “Ulibarri” was mentioned in relation to Banco Agrícola Comercial de Bilbao, constituted by Federación Católico-Social Navarra, the syndicate that Marcelino Ulibarri was related to in the early 1920s, Majuelo Gil, Pascual Bonis 1991, p. 116

- ^ single texts claim Ulibarri was employed in La Equitativa, but they never provide a source, compare Fernando Mikelarena Peña, Estructura, cadena de mando y ejecutores de la represión de boina roja en Navarra en 1936, [in:] Historia Contemporánea 53 (2016), p. 602, Mercedes Sánchez, Marcelino Ulibarri Eguiláz. El martillo de la Masonería, [in:] Asociación por la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica de Aragón service, available here, Diego Navarro Bonilla, Morir matando, Madrid 2012, ISBN 9788415177609, p. 213. The only primary source identified which confirms his relation with the company is El Noticiero 28.12.34, available here. La Equitativa appears also on later stages of his life, but not as his employer. Following the Nationalist seizure of Barcelona in January 1939 the local manager of La Equitativa offered to host DERD staff in the premises, Josep Cruanyes i Tor, L’espoliació del patrimoni documental i bibliogràfic de Catalunya durant la Guerra Civil espanyola (1937–1939), [in:] Lligall: revista catalana d'Arxivística 19 (2002), pp. 46-47. Similar offer has allegedly been made by a local Madrid manager of La Equitativa following the Nationalist seizure of the city in March 1939, José Tomás Velasco Sánchez, El archivo que perdía los papeles. El archivo de la guerra civil según el fondo documental de la Delegación de Servicios Documentales [PhD thesis Universidad de Salamanca], Salamanca 2017, p. 177

- ^ in 1924 he was listed in the press as a contact person for candidates interested in recruitment as “agentes en seguros, vida y incendios”, El Noticiero 10.05.24, available here

- ^ Petra Castiella, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Diario de Navarra 26.06.64

- ^ El Eco de Navarra 12.11.08, available here

- ^ Petra Castiella Perez, [in:] Geni service, available here

- ^ Diario de Navarra 07.11.70

- ^ it is not clear when the couple moved to Zaragoza. One source claims that they lived 25 years in the Aragonese capital, which given they moved out in 1934–35 points to the year of 1910, compare Ulibarri, Marcelino de (1880–1951) entry, [in:] PARES service, available here. Similar claim - “vivió desde los años diez en Zaragoza donde era representante de seguros de La Equitativa” – in Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 602. Another source claims that he moved to Zaragoza as a 10-year-old, compare “a los diez años se trasladó a vivir a Zaragoza, Mercedes Sánchez, Marcelino Ulibarri Eguiláz. El martillo de la Masonería, [in:] Asociación por la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica de Aragón service, available here

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 44

- ^ Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 602, similar claim in Un carlista gestó en Zaragoza el archivo de la Guerra Civil, [in:] Heraldo de Aragón 13.02.05

- ^ Ruiz de Ulibarri, Pedro entry, [in:] PARES service, available here. Ruiz de Ulibarri as a 16-year-old volunteered to requeté and was heavily wounded, with bullet going through his head; despite brain damage feared he recovered well. Unfit for military, he was later employed by his uncle in archivial service, María Isabel Ruiz de Ulíbarri, [in:] Fundación Ignacio Larramendi service, available here, also Hilari Raguer, Historias de Salamanca, [in:] Nabarralde service 28.02.13, available here, and Ulibarri, Marcelino de (1880–1951) entry, [in:] PARES service, available here

- ^ Fernando Mikelarena Peña, Sobre la implementación de la limpieza política franquista en Navarra en 1936–1937, [in:] Diacroniae. Studi di Storia Contemporanea 37/1 (2019), p. 14. It is not clear whether a Carlist general, Francisco Ulibarri Veramendi, who was born near Muez, was anyhow related

- ^ in 1865 Marcelino’s grandfather Ciriaco and his father Ignacio signed a long adhesion list, published in the Carlist press mouthpiece El Pensamiento Español 08.09.65, available here. In 1866 Ciriaco signed a subscription to commemorate the Traditionalist pundit Pedro de la Hoz, La Esperanza 05.03.66, available here. In the Carlist press he was referred to as “nuestro amigo”, compare El Pensamiento Español 13.02.69, available here

- ^ "Nací en 1918 en Allo, un pueblito navarro de Tierra Estella, en una familia de grandes recuerdos carlistas que se remontan ya a la primera guerra. En nuestra casa de Muez, “la casa de la Parra”, estuvo alojado don Carlos y doña Margarita durante la batalla de Abárzuza. Mi abuela solía contar historias de aquellos días; nos enseñaba las camas de hierro donde durmieron y la mesita donde doña Margarita preparaba hilas para los heridos. Crecimos en ese ambiente y esa lealtad a la Causa", María Isabel Ruiz de Ulíbarri, [in:] Fundación Ignacio Larramendi service, available here. The "abuela" mentioned in the account is Marcelino's mother, Hilaria Eguilaz

- ^ Diario de Avisos de Zaragoza 03.11.04, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 06.04.05, available here

- ^ El Correo Español 13.04.07, available here

- ^ Congreso de los Diputados. Diario de las sesiones, Madrid 1910, p. 17

- ^ El Noticiero 05.03.10, available here

- ^ El Noticiero 06.03.10, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 07.01.11, available here

- ^ El Noticiero 09.06.12, available here

- ^ El Noticiero 15.10.11, available here

- ^ Ulibarri is not a single time mentioned in a mongraphic work on Mellismo, Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820

- ^ the letter was co-signed with Carlist pundits Pascual Comin, Bernardo Elio, conde Rodezno, Joaquín Beunza, and Julian Elorza, La Reconquista 07.02.20, available here

- ^ La Crónica. Diario Independiente, 30.11.16, p. 3

- ^ the problem was related to sugarbeets, its overproduction and falling prices; Ulibarri advocated a joint, solidarity-based corporate action. In the press note there is no reference to any organisation or institution that Ulibarri might have represented, Heraldo de Aragon 04.03.18, available here

- ^ El Noticiero 09.05.23, available here

- ^ El Noticiero 09.02.29, available here

- ^ R. J. Campo, Un carlista gestó en Zaragoza el archivo de la Guerra Civil, [in:] Heraldo de Aragón 13.02.05

- ^ “extremamente religioso”, Marc Carillo, El Derecho represivo de Franco, Madrid 2023, ISBN 9788413642048, p. 88, “profundamente religioso”, José Antonio Ferrer Benimeli, La masonería en la España del siglo XX, Cuenca 1996, ISBN 9788489492479, p. 48

- ^ Majuelo Gil, Pascual Bonis 1991, p. 156

- ^ “a personal friend of Franco since the late 1920s”, Julius Ruiz, Franco’s Justice, London 2005, ISBN 9780191639265, p. 199; “amigo de Franco desde los tiempos en que este dirigía la Academia Militar de Zaragoza”, Marc Carillo, El Derecho represivo de Franco, Madrid 2023, ISBN 9788413642048, p. 88; “había trabado conocimiento y amistad estrecha con Franco justo en la época en que éste desempeñó el cargo de director de la Academia General Militar”, Diego Navarro Bonilla, Morir matando, Madrid 2012, ISBN 9788415177609, “persona de la máxima confianza tanto de Franco como de Serrano Suñer, a los que conocía de sus años en Zaragoza”, Nicolás Sesma, Ni una, ni grande, ni libre. La dictadura franquista, Barcelona 2024, ISBN 9788491996330, p. 66 “amic personal de Francisco Franco des del temps de l’Académia de Saragossa”, Andreu Ginés i Sànchez, La instauració del franquisme al País Valencià, Valencia 2011, ISBN 9788437083261, p. 236; “el carlí i antic company de Franco a l’Acadèmia General Militar”, Neus Moran Gimeno, L' espoli franquista dels ateneus catalans (1939–1984), Barcelona 2022, ISBN 9788418680182, p. 44; “a personal friend of Franco's since meeting at the Military Academy in Saragossa”, Toni Strubell, From pillage to reparation: the struggle for Salamanca papers, [in:] Fundacio Emili Darder Papers 2006 [online]; “en la ciudad aragonesa Ulíbarri trabó una estrecha relación con Franco”, Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 602; “vivió durante 25 años en Zaragoza, donde trabó una estrecha relación con Francisco Franco”, Ulibarri, Marcelino de (1880–1951) entry, [in:] PARES service, available here; “Marcelino de Ulibarri residí durant vint-i-cinc anys a Saragossa, on conegué a Francisco Franco i, sembla ser, també a Ramón Serrano Suñer”, Andreu Gínes Sánchez, Francisco Javier Planas de Tovar. El governador de la repressió, [in:] P. Páges i Blanch (ed.), La repressió franquista al País Valencía, Valencia 2009, ISBN ISBN 9788475028361, p. 592. Some authors even claim that Franco and Ulibarri were “brothers in arms”, compare “l’antic company d’armes del dictador a Saragossa”, El Sueño Igualitario, [in:] Cazarabet service 2005, available here

- ^ R. J. Campo, Un carlista gestó en Zaragoza el archivo de la Guerra Civil, [in:] Heraldo de Aragón 13.02.05

- ^ La Voz de Aragón 28.04.32, available here

- ^ Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054, p. 79

- ^ La Voz de Aragon 27.06.33, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 03.08.33, available here

- ^ Ulibarri is not a single time mentioned in the monographic work on Carlism in the republican era, compare Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931–1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521207294

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 26.03.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 19.02.35, available here

- ^ La Epoca 10.12.31, available here

- ^ La Voz de Aragón 28.04.32, available here

- ^ La Voz de Aragón 12.11.33, available here

- ^ Jesús Espinosa Romero, The Spanish Civil War Archive and the Construction of Memory, [in:] Alison Ribeiro de Menezes, Antonio Cazórla-Sánchez, Adrian Shubert (eds.), Public Humanities and the Spanish Civil War, s.l. 2018, ISBN 9783319972732, p. 48

- ^ Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 603. Serrano mentioned Ulibarri in his memoirs, though the phrasing suggested he barely knew him, Jesús Espinosa Romero, Sofía Rodríguez López, El archivo de Guerra Civil de Salamanca. De la campaña a la transición, [in:] Nicolás Ávila Seoane, Juan Carlos Galende Díaz, Susana Cabezas Fontanilla (eds.), Paseo documental por el Madrid de antaño, Madrid 2015, ISBN 9788460834786, p. 134

- ^ La Voz de Navarra 28.11.34, available here

- ^ where he employed 2 servants; a document from Ayuntamiento de Zaragoza, issued in 1935, Empadronamiento municipal, still counted him as resident R. J. Campo, Un carlista gestó en Zaragoza el archivo de la Guerra Civil, [in:] Heraldo de Aragón 13.02.05. In June 1935 he was visited in Zaragoza by a delegation from Juventud Carlista, El Siglo Futuro 08.06.35, available here

- ^ Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, p. 18

- ^ Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936–1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, p. 131

- ^ Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 603

- ^ Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 596

- ^ Javier Ugarte Tellería, El carlismo en la guerra del 36: la formación de un cuasi-estado nacional-corporativo y foral en la zona vasco-navarra, [in:] Historia Contemporanea 38 (2009), p. 64

- ^ Ignacio Tébar Rubio-Manzanares, Derecho penal del enemigo en el primer franquismo, Alacant 2018, ISBN 9788497175043, p. 49

- ^ Joan Corbalán Gil, Justícia, no venjança, Els executats pel franquisme a Barcelona (1939–1952), Barcelona 2008, ISBN 9788497913508, p. 36

- ^ Vicenta Cortés Alonso, Una cuestión de terminología y del uso de las preposiciones: ek Archivo General de la Guerra Civil, en Salamanca, [in:] Ebre 38 3 (2008), p. 155

- ^ Strubell 2006

- ^ Angels Bernal, Miquel Casademont, Antoni Mayans i Plujà, La documentació catalana a Salamanca, l'estat de la qüestió, 1936–2003, Barcelona 2003, ISBN 9788492248216, p. 111

- ^ later many among the DNAE and DERD staff believed Ulibarri was an army colonel; others thought he and his nephew were members of some rigorous religious order, Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 42

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 95

- ^ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 34

- ^ “no pueden saltarse las leyes para imponer la justicia”, quoted after Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 117

- ^ “seguir las normas que emplean los rojos”, quoted after Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 117

- ^ "Luego viene Berasaín con Ulibarri, Ezcurra, Arellano y Ortigosa. Me hablan de la necesidad de cambiar la Junta y nombrar en seguida la comisión que debe colaborar con el Partido Unico deseaddo por Franco", Jordi Canal i Morell, Banderas blancas, boinas rojas. Una historia política del carlismo, 1876–1939, Barcelona 2006, ISBN 9788496467347, p. 339

- ^ Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937–1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714, p. 34, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 267

- ^ with Martínez Berasain, conde Rodezno and conde Florida, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 267

- ^ Villanueva Martínez, 1998, p. 37, Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 45

- ^ Peñalba Sotorrío 2013, p. 56

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 44

- ^ “su correspondencia cruzada desvela la falta de sintonía con Falange al ser tan decididos anticomunistas y antimasones como convencidos tradicionalistas”, Julio Ponce Alberca, Los gobernadores civiles en el primer franquismo, [in:] Hispania. Revista Española de Historia 252 (2016), pp. 262-263

- ^ OIPA was to be composed of 3 members, Manuel Maestro y Maestro, Juan Fuentes Bertrán, and Eduardo Galán Ruiz. According to some sources, its predecessor was Sección Judeomasónica in Servicio de Información Militar, Vicent Sampedro Ramo, Los hijos de la viuda. La masonería en la ciudad de Alicante (1893–1939), Alacant 2023, ISBN 9788497178259, p. 503

- ^ Susana Belenguer, Claran Crosgrove, James Whiston (eds.), Living the Death of Democracy in Spain. The Civil War and Its Aftermath, London 2017, ISBN 9781317525431, p. 175

- ^ Alejandro Pérez-Olivares García, Madrid cautivo. Ocupación y control de una ciudad (1936–1948), Valencia 2020, ISBN 9788491346494, p. 44, also Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 603, also Gómez Bravo, Marco Carretero 2011, p. 185

- ^ see e.g. Guillermo Portilla Contreras, El derecho penal bajo la dictadura franquista. Bases ideológicas y protagonistas, Madrid 2022, ISBN 9788411221399, Javier Alvarado Planas, Masones en la nobleza de España. Una hermandad de iluminados, Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788490606124; Ana Martínez Rus, Verónica Sierra Blas, Libros culpables: hogueras, expurgos y depuraciones. La política represiva del franquismo (1936–1945), [in:] Antoni Segura, Andreu Mayayo, Teresa Abelló (eds.), La dictadura franquista. La institucionalització d’un règim, Barcelona 2010, ISBN 9788447535538; Marta Velasco Contreras, Los otros mártires, Madrid 2012, ISBN 9788496797581; Diego Navarro Bonilla, Derrotado, pero no sorprendido. Reflexiones sobre la información secreta en tiempo de guerra, Madrid 2007, ISBN 9788496780323; Manuel Según Alonso, La masonería madrileña en la primera mitad del siglo XX, Madrid 2019, ISBN 978841776590

- ^ most historiographic works dwell, sometimes in detail, on setup of OIPA, but none provides information on how it disappeared. From some it appears that in late spring of 1937 it was sort of divided into DNAE and SRD, compare Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura service, available here. From some it appears that in the spring of 1938 OIPA, DNAE and SRD were all merged into DERD, see Espinosa Romero, Rodríguez López 2015, pp. 135-137

- ^ Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura service, available here

- ^ María José Turrión García, La biblioteca de la Sección Guerra Civil del Archivo Histórico Nacional (Salamanca), [in:] Boletín de ANABAD 47/2 (1997), p. 90

- ^ original decree has not survived until today, see Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 31, so there are some doubts as to its exact stipulations

- ^ Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 603, Josep Cruanyes i Tor, L’espoliació del patrimoni documental i bibliogràfic de Catalunya durant la Guerra Civil espanyola (1937–1939), [in:] Lligall: revista catalana d'Arxivística 19 (2002), p. 40. The institution might appear in literature also as Delegación Nacional de Servicios Especiales, Delegación de Asuntos Especiales, Asuntos Especiales or Sección Especial

- ^ Espinosa Romero 2018, p. 48

- ^ “Ulibarri would be charged with organizing two new services”, Espinosa Romero 2018, p. 48, "al frente de ambos organismos [Franco] nombró a un carlista de su confianza, Marcelino de Ulibarri y Eguilaz", Leandro Álvarez Rey, Los Diputados por Andalucía de la Segunda República 1931–1939, Sevilla 2009, ISBN 9788461313266, p. 96. One author claims the name of the institution was "Servicios Especiales de Recuperación de Fondos Masónicos", Carles Quevedo i García, Els (mal)anomenats papers de Salamance i el Solsonèz. Un solsoní a l’Oficina de Recupercaión de Documentos (1937–1939), [in:] Oppidum. Revista Cultural del Solsonès 9 (2011), p. 87

- ^ Martínez Rus 2010, p. 148

- ^ Espinosa Romero, Rodríguez López 2015, p. 135

- ^ Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura service, available here

- ^ compare e.g. Carillo 2023, p. 88, Ruiz 2005, p. 199, Navarro Bonilla 2012, p. 122, Sesma 2024, p. 66, Ginés i Sànchez 2011, p. 236, Moran Gimeno 2022, p. 44, Toni Strubell 2006, Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 602, Gínes Sánchez, Javier Planas de Tovar 2009, p. 592

- ^ “persona de la máxima confianza tanto de Franco como de Serrano Suñer, a los que conocía de sus años en Zaragoza”, Sesma 2024, p. 66, “Marcelino de Ulibarri residí durant vint-i-cinc anys a Saragossa, on conegué a Francisco Franco i, sembla ser, també a Ramón Serrano Suñer”, Gínes Sánchez 2009, p. 592, “Ulibarri had ingratiated himself with Serrano”, Rudolf Savundra, Blue blood, blue shirt. The role of the Conde de Mayalde during the Franco dictatorship in Spain [MA thesis University of London], London 2020, p. 51, “fervoso católico y de absoluta confianza del recién estrenado ministro del Interior, Ramón Serrano Suñer”, Marta Velasco Contreras, Los otros mártires, Madrid 2012, ISBN 9788496797581, p. 44. However, some works claim that it was Ulibarri who promoted Serrano, not the other way round, see e.g. “Ulibarri had also been instrumental in promoting the political career of Franco’s brother-in-law, Ramón Serran Suñer”, Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust, London 2012, ISBN 9780393239669, p. 311

- ^ Pérez-Olivares 2020, p. 38. As a source the author quotes a work which deals with Carlist propaganda structures in early months of the war. The work quoted mentions Ulibarri, but not as the one involved in propaganda, compare Ricardo Ollaquindia, La Oficina de Prensa y Propaganda Carlista de Pamplona al comienzo de la guerra de 1936, [in:] Principe de Viana 56/2-5 (1995), pp. 485-508

- ^ in 1937 Ulibarri met Franco and again and argued in favor of Fal, but again criticised Junte Central for creating “una atmósfera muy difícil para el Carlismo a nivel nacional frente al Poder militar”, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 247

- ^ Turrión García 1997, p. 90

- ^ Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura service, available here

- ^ Mikel Aizpuru, Urko Apaolaza, Jesús Mari Gómez, Jon Odriozola, El otoño de 1936 en Guipúzcoa. Los fusilamientos de Hernani, Donostia 2006, ISBN 9788496643680, p. 126

- ^ Cruanyes i Tor 2002, p. 42, Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 149

- ^ Gómez Bravo, Marco Carretero 2011, pp. 161–162

- ^ extensive treatment of the issue in Velasco Sánchez 2017

- ^ Boletín Oficial del Estado 553, 27.04.38

- ^ José-Tomás Velasco Sánchez, El Museo de la masonería del Centro documental de la Memoria Histórica de Salamanca, [in:] REHMLAC 2016, [online]

- ^ Espinosa Romero 2018, p. 50

- ^ some authors claim that DNAE existed until 1944, when merged into DNSD, José-Tomás Velasco Sánchez, Las agrupaciones documentales del frente oriental de la guerra civil custodiadas en el Archivo de Salamanca [in:] Ebre 38 9 (2019), p. 159

- ^ Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, [in:] Ministerio de Cultura service, available here

- ^ “objetivo era unificar los servicios de información que habían quedado huérfanos al desaparecer la Secretaría General del Generalísimo”, Espinosa Romero, Rodríguez López 2015, p. 137, “it [OIPA] now took on the name of Delegación del Estado para la Recuperación de Documentos (DERD)”, Peter Anderson, The ‘Salamanca Papers’: Plunder, Collaboration, Surveillance and Restitution, [in:] Susana Bayó Belenguer, Ciaran Cosgrove, James Whiston (eds.), Living the Death of Democracy in Spain, London 2015, ISBN 978113884760, p. 177

- ^ however, as late as in October 1938 in the press Ulibarri still appeared as “jefe de la Delegación de Servicios Especiales”, Diario de Burgos 27.10.38, available here a

- ^ La Rioja 13.05.38, available here

- ^ Turrión García 1997, p. 91

- ^ José-Tomás Velasco Sánchez, Las agrupaciones documentales del frente oriental de la guerra civil custodiadas en el Archivo de Salamanca [in:] Ebre 38 9 (2019), pp. 174-178

- ^ in the Salamanca archive the Navarros were heavily overrepresented, as there were 88 of them employed out of the total staff of 397, Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 53

- ^ buildings taken over for archive and residence of DERD staff were subject to upgrade, with new electricity system and fire installations mounted, Velasco Sánchez 2017, pp. 57-58

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 67

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 76

- ^ Ruiz 2005, p. 199

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 125

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2019, p. 165. According to other source the DERD staff sent to Barcelona numbered 50 people, Comissio de la Dignitat, The Archives Franco Stole from Catalonia, Lleida 2004, p. 13

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2019, p. 165

- ^ Neus Moran Gimeno, El CADCI. Guerra i memoria espoliada (1936–1939), Barcelona 2018, p. 4

- ^ Espinosa Romero 2018, p. 50

- ^ “auténtico experto en la concepción de la guerra y de la depuración desde los despachos”, Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 619

- ^ Cruanyes i Tor 2002, p. 49

- ^ Servicio de Información y Policía Militar

- ^ clashes with Tusquets were related to the latter’s reluctancy to hand over his archive to DERD, Paul Preston, A Catalan Contribution to the Myth of the Jewish-Bolshevik-Masonic Conspiracy, [in:] Alejandro Quiroga, Miguel Ángel del Arco Blanco (eds.), Right-Wing Spain in the Civil War Era. Soldiers of God and Apostles of the Fatherland, 1914–45, London 2012, ISBN 9781441114792, p. 193.

- ^ see e.g. comments on Ulibarri’s relations with the Dirección General de Seguridad director, José Finat y Escrivá de Romaní, Savundra 2020, p. 51

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 153

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 190

- ^ in November 1939 Ulibarri admitted struggling with 700 tons of uncategorized documents, Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 126

- ^ he tried to move the archive to Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial in 1939, to Colegio de Nuestra Señora de Loreto in Hortaleza (Madrid) in 1940–1941, to Palacio de Orellana or Palacio del Marqués de Albaida (Sala) in 1941 and then to Colegio de Solís de Alcalá de Henares (Madrid) in 1941, José-Tomás Velasco Sánchez, El Museo de la masonería del Centro documental de la Memoria Histórica de Salamanca, [in:] REHMLAC 2016, [online]

- ^ it was launched in 1941, located in Colegio de San Ambrosio as 2 rooms, but was not opened to wide public, and remained operational until 1967, compare detailed discussion in Velasco Sánchez 2016

- ^ Gómez Bravo, Marco Carretero 2011, p. 173

- ^ great mobility of numerous individuals who used to reside in the former Republican zone posed a problem for Francoist security, as they found it difficult to collect information on past activities of a person in all his/her previous locations; “certificado” was supposed to tackle the problem, Gómez Bravo, Marco Carretero 2011, p. 175

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 45

- ^ Portilla Contreras 2022, p. 315

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, pp. 42, 45

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2019, p. 159

- ^ Comissio de la Dignitat 2004, p. 19

- ^ Gómez Bravo, Marco Carretero 2011, p. 38

- ^ Gómez Bravo, Marco Carretero 2011, p. 173

- ^ Juan José Morales Ruiz, La Ley de Represión de la Masonería y el Comunismo (1 de marzo de 1940). Un estudio de algunos aspectos histórico-jurídicos, [in:] Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña 12/1-2 (2020), p. 166

- ^ the military had their own Tribunales de Honor, BOE 62 02.03.40

- ^ other members of TERMC were Francisco Borbón de la Torre, Juan Granell Pascual, Isaias Sánchez Tejerias and Antonio Luna García, Jurisdicción especial para la represión de la masonería y el comunismo, [in:] PARES service, available here

- ^ compare e.g. “Marcelino Ulibarri de Eguilaz era un carlista de origen navarro de hondas convicciones religiosas que se tomó como una cuestión personal su lucha contra la masonería y el comunismo”, Juan Ignacio González Orta, Carlistas y falangistas en la provincia de Huelva: de la lucha contra la república al movimiento nacional [PhD thesis Universidad de Huelva], Huelva 2022, p. 381

- ^ Ricardo Robledo (ed.), Esta salvaje pesadilla. Salamanca en la guerra civil española, Barcelona 2007, p. 148

- ^ he wrote that “Habrá que huir de la excesiva preocupación legalista que llenará el procedimiento de requisitos formales, plazos, trámites, escritos, vistas y recursos. Óigase a los enjuiciados en la forma estricta suficiente para llenar la exigencia natural de no condenar a nadie sin ser oído”, also “y nada de exigir la intervención de Letrado, ni de consentir debates orales, ni de vistas públicas”, quoted after Eduardo Fernández Redondo, El derecho penal de autor en al franquismo: la represión sobre la masonería y el comunismo [MA thesis Universidad de Jaen], Jaen 2019, p. 16

- ^ Julius Ruiz, Fighting the International Conspiracy: The Francoist Persecution of Freemasonry, 1936–1945 [in:] Politics, Religion & Ideology 12/2 (2011), p. 188

- ^ Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Guadalajara 07.04.41, available here

- ^ Morales Ruiz 2020, p. 174

- ^ Morales Ruiz 2020, pp. 183

- ^ Fernández Redondo 2019, p. 25

- ^ Espinosa Romero 2018, p. 51

- ^ Noran Gimeno 2018, p. 5

- ^ Portilla Contreras 2022, p. 315

- ^ Fernando Sigler Silvera, Persecución contra un benefactor de la República: el acoso judicial contra Elíás Ahuja por sus relaciones con la masonería, [in:] J. A. Ferrer Benimeli (ed.), La Masonería Española. Represión y exilios, Zaragoza 2010, p. 789

- ^ the list of appointees was not compiled in alphabetic order, El Diario de Avila 13.09.39, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 65

- ^ El Adelantado 23.11.42, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 178

- ^ compare e.g. Ismael Saz, Fascismo y franquismo, Valencia 2004, ISBN 9788437059105, p. 165, and Stanley G. Payne, The Franco Regime, Madison 1987, ISBN 9780299110741, p. 324

- ^ Jornada 12.02.43, available here, see also Ulibarri’s 1943 mandate on the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Boletin Oficial de la Provincia de Zaragoza 07.05.46, available here

- ^ see Ulibarri’s 1946 mandate on the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Diario de Burgos 05.05.49, available here

- ^ see Ulibarri’s 1949 mandate on the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ see e.g. his works on planned Regimen de Donativos, Libertad 03.04.43, available here

- ^ Andreu Ginés i Sánchez, La instauració del franquisme al País Valenciá: Castelló de la Plana i Valéncia [PhD thesis Universitat Pompeu Fabra], Barcelona 2008, p. 1122

- ^ Imperio 01.04.44, available here

- ^ Correo de Mallorca 20.07.44, available here

- ^ in a massive monographic work on early-post-war Navarrese Carlism he is mentioned only in relation to his wartime activity, see Villanueva Martínez 1998, pp. 34, 37, 65, 178, 305, 538

- ^ Martorell Pérez 2009, also Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939–1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015, Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997, ISBN 9788431315641, Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965–1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015

- ^ Josep Miralles Climent, Depuraciones en Euskalerria 1936–39, [in:] Noticias de Gipuzkoa 16.11.20, available here

- ^ La Prensa 13.03.51, available here

- ^ see references to “viejo requeté”, La Rioja 14.03.51, available here

- ^ in digital archives of Spanish press he is mentioned in this role only at one point, namely after his appointment in May 1938, see e.g. La Rioja 13.05.38, available here

- ^ Joaquín Arrarás, Historia de la Segunda República Española, vol. V, Madrid 1968, p. 320

- ^ Eduardo Alvarez Puga, Historia de la Falange, Madrid 1969, p. 152

- ^ compare e.g. Carillo 2023, p. 88, Ginés i Sànchez 2011, p. 236, Gínes Sánchez, Javier Planas de Tovar 2009, p. 592, Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 602, Moran Gimeno 2022, Navarro Bonilla 2012, p. 122, p. 44, Preston 2012, p. 193, Ruiz 2005, p. 199, Sesma 2024, p. 66

- ^ Espinosa Romero 2018, p. 51

- ^ Preston 2012, p. 311

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, pp. 69-70

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 73

- ^ Morales Ruiz 2020, pp. 174-175

- ^ he was not member of Cuerpo Facultativo de Archiveros, and when struggling with numerous issues related to his database, he sought professional assistance from Archivo General de Simancas, Velasco Sánchez 2017, p. 123

- ^ El Sueño Igualitario, [in:] Cazarabet service 2005, available here

- ^ Gutmaro Gómez Bravo, Jorge Marco Carretero, La obra del miedo. Violencia y sociedad en la España franquista 1936–1950, Barcelona 2011, ISBN 9788499420912, p. 159

- ^ some works mention La Equitativa, but never with a source, compare Mikelarena Peña 2016, p. 602, Navarro Bonilla 2012, p. 213. In the press during 25 years of his Zaragoza spell he was only once mentioned as related to the company, El Noticiero 28.12.34, available here

- ^ Tébar Rubio-Manzanares 2018, p. 49, Corbalán Gil 2008, p. 36, Cortés Alonso 2008, p. 155, Bernal, Casademont, Mayans i Plujà 2003, p. 111

- ^ Velasco Sánchez 2017

- ^ see tha chapter Marcelino de Ulibarri y Eguilaz, un germen antimasónico omnipresente en la represion in María José Turrión García, La represión de la masonería femenina en el Tribunal de Represión de la Masoneríá y el Comunismo (1940–1963) [PhD thesis Universidad de Salamanca], Salamanca 2020, pp. 94-103

Further reading[edit]

- María José Turrión García, La represión de la masonería femenina en el Tribunal de Represión de la Masoneríá y el Comunismo (1940–1963) [PhD thesis Universidad de Salamanca], Salamanca 2020

- José Tomás Velasco Sánchez, El archivo que perdía los papeles. El archivo de la guerra civil según el fondo documental de la Delegación de Servicios Documentales [PhD thesis Universidad de Salamanca], Salamanca 2017

External links[edit]

- Carlists

- FET y de las JONS politicians

- Members of the Cortes Españolas

- Members of the National Council of the FET-JONS

- People from Tafalla (comarca)

- People from Zaragoza

- Perpetrators of political repression in Francoist Spain

- Politicians from Navarre

- Spanish archivists

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- Spanish anti-communists

- Spanish civil servants

- Spanish far-right politicians

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction)

- Spanish rebels