Mary Jane Kelly

Mary Jane Kelly | |

|---|---|

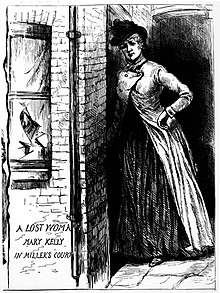

Sketch in The Penny Illustrated Paper (24 November 1888) | |

| Born | c. 1863 |

| Died | 9 November 1888 (aged c. 25) |

| Body discovered | 13 Miller's Court, Dorset Street in Spitalfields, London, England 51°31′7.16″N 0°4′30.47″W / 51.5186556°N 0.0751306°W |

| Occupation | Prostitution |

Mary Jane Kelly (c. 1863 – 9 November 1888), also known as Marie Jeanette Kelly, Fair Emma, Ginger, Dark Mary, and Black Mary, is widely believed to have been the final victim of the notorious unidentified serial killer Jack the Ripper, who killed and mutilated several women in the Whitechapel area of London from late August to early November 1888. She was about 25 years old and living in poverty at the time of her death. Template:Ripper victims

Early life

Compared with other Ripper victims, Kelly's origins are obscure and undocumented, and much of it is possibly embellished. Kelly may have herself fabricated many details of her early life as there is no corroborating documentary evidence, but there is no evidence to the contrary either.[1] According to Joseph Barnett, the man she had most recently lived with prior to her murder, Kelly had told him she was born in Limerick, Ireland, in around 1863—although whether she referred to the city or the county is not known—and that her family moved to Wales when she was young.[2]

Barnett reported that Kelly had told him her father was named John Kelly and that he worked in an iron works in either Caernarfonshire or Carmarthenshire.[3] Barnett also recalled Kelly mentioning having seven brothers and at least one sister.[4] One brother, named Henry, supposedly served in the 2nd Battalion Scots Guards.[3] She once stated to her friend Lizzie Albrook that a family member was employed at the London theatrical stage. Her landlord, John McCarthy, claimed that Kelly received infrequent correspondence from Ireland.[5]

Both Barnett and a reported former roommate named Mrs. Carthy claimed that Kelly came from a family of "well-to-do people". Carthy reported Kelly being "an excellent scholar and an artist of no mean degree"—but at the inquest, Barnett informed the coroner that she often asked him to read the newspaper reports of the murders to her, suggesting that she was illiterate.[6]

Around 1879, Kelly was reportedly married to a coal miner named Davies, who was killed two or three years later in a mine explosion. She claimed to have stayed for eight months in an infirmary in Cardiff, before moving in with a cousin. Although there are no contemporary records of Kelly's presence in Cardiff, it is at this stage in her life that Kelly is considered to have begun her career as a prostitute.[7]

Return to London

In 1884, Kelly apparently left Cardiff for London and found work in a brothel in the more affluent West End of London. Reportedly, she was invited by a client to France, but returned to England within two weeks,[8] having disliked her life there.[9] Nonetheless, it is believed to be at this stage in her life that Kelly chose to adopt the French name "Marie Jeanette".[10] Social historian Hallie Rubenhold, who wrote a biography of the canonical five victims, uncovered evidence that Kelly escaped from human trafficking while in France. Rubenhold then posits that this experience forced Kelly to move from the West End to the East End, in order to hide from those who tried to traffic her.[11]

Appearance and habits

Kelly has been variously reported as being a blonde or redhead, whereas her nickname, "Black Mary", suggests a dark brunette. Her reported eye colour was blue. Reports of the time estimated her height at 5 feet and 7 inches (1.70 metres). Detective Walter Dew, in his autobiography, claimed to have known Kelly well by sight and described her as "quite attractive" and "a pretty, buxom girl".[12] He said she always wore a clean white apron but never a hat. Sir Melville Macnaghten of the Metropolitan Police Force, who never saw her in the flesh, reported that she was known to have "considerable personal attractions" by the standards of the time. The Daily Telegraph of 10 November 1888 described her as "tall, slim, fair, of fresh complexion, and of attractive appearance".[13] By some, Kelly had been known as "Fair Emma", although it is unclear whether this reference applied to her hair colour, her skin colour, her beauty, or whatever other qualities that she possessed. Some newspaper reports claim she was nicknamed "Ginger" after her allegedly ginger-coloured hair (though sources disagree even on this point, thus leaving a large range from ash blonde to dark chestnut). Another paper claimed she was known as "Mary McCarthy", which may have been a mix up with the surname of her landlord at the time of her death. Gravitating toward the poorer East End of London, she reportedly lived with a man named Morganstone near the Commercial Gas Works in Stepney, and later with a mason's plasterer named Joe Flemming.[14]

When drunk, Kelly would often be heard singing Irish songs; in this state, she would often become quarrelsome and even abusive to those around her, which earned her the nickname "Dark Mary." McCarthy said "she was a very quiet woman when sober but noisy when in drink."[15] Barnett first met Kelly in April 1887.[4] The two agreed to live together on their second meeting the following day.[16] In early 1888 they both moved into 13 Miller's Court, a furnished single room at the back of 26 Dorset Street, Spitalfields. It was a single twelve-foot square room, with a bed, three tables and a chair. Above the fireplace hung a print of "The Fisherman's Widow". Kelly's door key was lost, so she bolted and unbolted the door from outside by putting a hand through a broken window beside the door.[1] A German neighbour, Julia Venturney, claimed Kelly had broken the window when drunk.[17] Barnett worked as a fish porter at Billingsgate Fish Market, but when he fell out of regular employment and tried to earn money as a market porter, Kelly turned to prostitution again. A quarrel ensued over Kelly's sharing of the room with another prostitute whom Barnett knew only as "Julia" and he left on 30 October, more than a week before her death, while continuing to visit Kelly.[18]

Night of the murder

Barnett visited Kelly for the last time between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m. on 8 November. He found her in the company of Maria Harvey, a friend of hers, and Harvey and Barnett left at about the same time.[19] Barnett returned to his lodging house, where he played cards with other residents until falling asleep at about 12:30.[20]

Fellow Miller's Court resident and prostitute, Mary Ann Cox, who described herself as "a widow and unfortunate",[21] reported seeing Kelly returning home drunk in the company of a stout ginger-haired man wearing a bowler hat and carrying a can of beer at about 11:45 p.m. Cox and Kelly wished each other goodnight. Kelly went into her room with the man and then started singing the song "A Violet I Plucked from Mother's Grave When a Boy." She was still singing when Cox went out at midnight, and when she returned an hour later at 1:00.[22] Elizabeth Prater had the room above Kelly's and when she went to bed at 1:30, the singing had stopped.[23]

Labourer George Hutchinson, who knew Kelly, reported that she met him at about 2:00 a.m. and asked him for a loan of sixpence. He claimed to be broke and that as Kelly went on her way she was approached by a man of "Jewish appearance". Hutchinson later gave the police an extremely detailed description of the man right down to the colour of his eyelashes despite it being the middle of the night.[24] He reported that he overheard them talking in the street opposite the court where Kelly was living; Kelly complained of losing her handkerchief, and the man gave her a red one of his own. Hutchinson claimed that Kelly and the man headed for her room, that he followed them, and that he saw neither one of them again, laying off his watch at about 2:45.[25] Hutchinson's statement appears to be partly corroborated by laundress Sarah Lewis, who reported seeing a man watching the entrance to Miller's Court as she passed into it at about 2:30 to spend the night with some friends, the Keylers.[26] Hutchinson claimed that he was suspicious of the man because although Kelly seemed to know him, his opulent appearance made him seem very unusual in that neighbourhood, but only reported this to the police after the inquest on Kelly had been hastily concluded.[27] Abberline, the detective in charge of the investigation, thought Hutchinson's information was important and sent him out with officers to see if he could see the man again.[28] Hutchinson's name does not appear again in the existing police records, and so it is not possible to say with certainty whether his evidence was ultimately dismissed, disproven, or corroborated.[27] In his memoirs Walter Dew discounts Hutchinson on the basis that his sighting may have been on a different day, and not the morning of the murder.[29] Robert Anderson, head of the CID, later claimed that the only witness who got a good look at the killer was Jewish. Hutchinson was not a Jew, and thus not that witness.[30] Some modern scholars have suggested that Hutchinson was the Ripper himself, trying to confuse the police with a false description, but others suggest he may have just been an attention seeker who made up a story he hoped to sell to the press.[31]

Cox returned home again at about 3:00. She reported hearing no sound and seeing no light from Kelly's room.[32] Elizabeth Prater, who was woken by a kitten walking over her neck, and Sarah Lewis both reported hearing a faint cry of "Murder!" at about 4:00 a.m., but did not react because they reported that it was common to hear such cries in the East End.[33] She claimed not to have slept and to have heard people moving in and out of the court throughout the night.[34] She thought she heard someone leaving the residence at about 5:45 a.m.[35] Prater did leave at 5:30 a.m., to go to the Ten Bells public house for a drink of rum, and saw nothing suspicious.[36]

Discovery

On the morning of 9 November 1888, the day of the annual Lord Mayor's Day celebrations, Kelly's landlord John McCarthy sent his assistant, ex-soldier Thomas Bowyer, to collect the rent. Kelly was six weeks behind on her payments, owing 29 shillings.[37] Shortly after 10:45 a.m., Bowyer knocked on her door but received no response. He reached through the crack in the window, pushed aside a coat being used as a curtain and peered inside—discovering Kelly's horribly mutilated corpse lying on the bed. She died at about 4:30AM.[38]

The Manchester Guardian of 10 November 1888 reported that Sgt Edward Badham accompanied Inspector Walter Beck to the site of 13 Miller's Court after they were both notified of Kelly's murder by a frantic Bowyer. Beck told the inquest that he was the first police officer at the scene and Badham may have accompanied him, but there are no official records to confirm Badham being with him. Edward Badham was on duty at Commercial Street police station on the evening of 12 November 1888. The inquest into the death of Mary Kelly had been completed earlier that day, when at around 6 p.m. George Hutchinson arrived at the station to give his initial statement to Badham.[39]

The wife of a local lodging-house deputy, Caroline Maxwell, claimed to have seen Kelly alive at about 8:30 on the morning of the murder, though she admitted to only meeting her once or twice before;[40] moreover, her description did not match that of those who knew Kelly more closely. Maurice Lewis, a tailor, reported seeing Kelly at about 10:00 that same morning in a pub. Both statements were dismissed by the police since they did not fit the accepted time of death; moreover, they could find no one else to confirm the reports.[41] Maxwell may have either mistaken someone else for Kelly, or mixed up the day she had seen her.[42] Such confusion was used as a plot device in the graphic novel From Hell (and subsequent movie adaptation).

The scene was attended by Superintendent Thomas Arnold and Inspector Edmund Reid from Whitechapel's H Division, as well as Frederick Abberline and Robert Anderson from Scotland Yard. Arnold had the room broken into at 1:30 p.m. after the possibility of tracking the murderer from the room with bloodhounds was dismissed as impractical.[43] A fire fierce enough to melt the solder between a kettle and its spout had burnt in the grate, apparently fuelled with clothing. Inspector Abberline thought Kelly's clothes were burnt by the murderer to provide light, as the room was otherwise only dimly lit by a single candle.[44]

The mutilation of Kelly's corpse was by far the most extensive of any of the Whitechapel murders, probably because the murderer had more time to commit his atrocities in a private room rather than in the street.[45] Dr. Thomas Bond and Dr. George Bagster Phillips examined the body. Phillips[46] and Bond[47] timed her death to about 12 hours before the examination. Phillips suggested that the extensive mutilations would have taken two hours to perform,[46] and Bond noted that rigor mortis set in as they were examining the body, indicating that death occurred between 2 and 8:00 a.m.[48] Bond's notes read:

The body was lying naked in the middle of the bed, the shoulders flat but the axis of the body inclined to the left side of the bed. The head was turned on the left cheek. The left arm was close to the body with the forearm flexed at a right angle and lying across the abdomen. The right arm was slightly abducted from the body and rested on the mattress. The elbow was bent, the forearm supine with the fingers clenched. The legs were wide apart, the left thigh at right angles to the trunk and the right forming an obtuse angle with the pubis.

The whole of the surface of the abdomen and thighs was removed and the abdominal cavity emptied of its viscera. The breasts were cut off, the arms mutilated by several jagged wounds and the face hacked beyond recognition of the features. The tissues of the neck were severed all round down to the bone.

The viscera were found in various parts viz: the uterus and kidneys with one breast under the head, the other breast by the right foot, the liver between the feet, the intestines by the right side and the spleen by the left side of the body. The flaps removed from the abdomen and thighs were on a table.

The bed clothing at the right corner was saturated with blood, and on the floor beneath was a pool of blood covering about two feet square. The wall by the right side of the bed and in a line with the neck was marked by blood which had struck it in several places.

The face was gashed in all directions, the nose, cheeks, eyebrows, and ears being partly removed. The lips were blanched and cut by several incisions running obliquely down to the chin. There were also numerous cuts extending irregularly across all the features.

The neck was cut through the skin and other tissues right down to the vertebrae, the fifth and sixth being deeply notched. The skin cuts in the front of the neck showed distinct ecchymosis. The air passage was cut at the lower part of the larynx through the cricoid cartilage.

Both breasts were more or less removed by circular incisions, the muscle down to the ribs being attached to the breasts. The intercostals between the fourth, fifth, and sixth ribs were cut through and the contents of the thorax visible through the openings.

The skin and tissues of the abdomen from the costal arch to the pubes were removed in three large flaps. The right thigh was denuded in front to the bone, the flap of skin, including the external organs of generation, and part of the right buttock. The left thigh was stripped of skin fascia, and muscles as far as the knee.

The left calf showed a long gash through skin and tissues to the deep muscles and reaching from the knee to five inches above the ankle. Both arms and forearms had extensive jagged wounds.

The right thumb showed a small superficial incision about one inch long, with extravasation of blood in the skin, and there were several abrasions on the back of the hand moreover showing the same condition.

On opening the thorax it was found that the right lung was minimally adherent by old firm adhesions. The lower part of the lung was broken and torn away. The left lung was intact. It was adherent at the apex and there were a few adhesions over the side. In the substances of the lung there were several nodules of consolidation.

The pericardium was open below and the heart absent. In the abdominal cavity there was some partly digested food of fish and potatoes, and similar food was found in the remains of the stomach attached to the intestines.[49]

Phillips believed that Kelly had been killed by a slash to the throat and the mutilations performed afterwards.[50] Bond stated in a report that the knife used was about 1 in (25 mm) wide and at least 6 in (150 mm) long, but did not believe that the murderer had any medical training or knowledge. He wrote:

In each case the mutilation was inflicted by a person who had no scientific nor anatomical knowledge. In my opinion, he does not even possess the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer or a person accustomed to cut up dead animals.[51]

Her body was taken to the mortuary in Shoreditch rather than the one in Whitechapel, which meant that the inquest was opened by the coroner for North East Middlesex, Dr. Roderick Macdonald, MP, instead of Wynne Edwin Baxter, the coroner who handled many of the other Whitechapel murders. The speed of the inquest was criticised in the press;[52] Macdonald heard the inquest in a single day at Shoreditch Town Hall on 12 November.[53] She was officially identified by Barnett, who said he recognised her by "the ear and the eyes",[54] and McCarthy was also certain the body was Kelly's.[41] Her death was registered in the name "Marie Jeanette Kelly", aged 25.[55]

Burial

Kelly was buried in the Roman Catholic Cemetery at Leytonstone on 19 November 1888. Her obituary ran as follows:

The funeral of the murdered woman Kelly has once more been postponed. Deceased was a Catholic, and the man Barnett, with whom she lived, and her landlord, Mr. M. Carthy, desired to see her remains interred with the ritual of her Church. The funeral will, therefore, take place tomorrow [19 Nov] in the Roman Catholic Cemetery at Leytonstone. The hearse will leave the Shoreditch mortuary at half-past twelve.

The remains of Mary Janet [sic] Kelly, who was murdered on 9 Nov in Miller's-court, Dorset-street, Spitalfields, were brought yesterday morning from Shoreditch mortuary to the cemetery at Leytonstone, where they were interred.

No family member could be found to attend the funeral.[56]

Theories

Extensive house-to-house enquiries and searches were conducted by police.[57] On 10 November, Dr. Bond wrote a report linking Kelly's murder with four previous ones—those of Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, and Catherine Eddowes—and providing a likely profile of the murderer.[58] On the same day, the government offered a pardon for "any accomplice, not being the person who contrived or actually committed the murder, who shall give such information and evidence as shall lead to the discovery and conviction of the murderer or murderers".[59] Despite the offer, and a massive police investigation, no one was ever charged or tried for the murders. No similar murder was committed for the next six months, as a result of which the police investigation was gradually wound down.[60] Kelly is generally considered to have been the Ripper's final victim, and it is assumed that the crimes ended because of the culprit's death, imprisonment, institutionalisation, or emigration.[61]

Abberline questioned Kelly's former roommate, Joe Barnett, for four hours after her murder, and his clothes were examined for bloodstains, but he was then released without charge.[62] A century after the murder, authors Paul Harrison and Bruce Paley proposed he killed Kelly in a jealous rage, or because she scorned him, and suggested that he committed the other murders to scare Kelly off the streets and out of prostitution.[62] Other authors suggest Barnett killed Kelly only, and mutilated her body to make it look like a Ripper murder.[63] Abberline's investigation appears to have exonerated him.[64] Other acquaintances of Kelly's put forward as her murderer include her landlord John McCarthy and her former boyfriend Joseph Fleming.[65] (The state of undress of Kelly's body, and her folded clothes on a chair, have led to suggestions that she undressed herself before lying down on the bed, which would indicate that she was either killed by someone she knew, or believed to be a client.[66])

In 2005, author Tony Williams claimed that Kelly had been found on the 1881 census return for Brymbo, near Wrexham. This claim was made on the basis that living next door to the Kelly family was a bachelor named Jonathan Davies, who could have been the "Davies" or "Davis" whom Joseph Barnett claimed had married Kelly when she was 16. This claim is almost certainly wrong, because if her husband was indeed killed two or three years later, this Jonathan Davies could not have been him: he was still alive and residing in Brymbo, as shown on the 1891 census return. In any case, hardly any of the details given by Barnett matched those of the family in Brymbo in 1881. Brymbo is in Denbighshire, not Carmarthen or Caernarfon, and the father was one Hubert Kelly, not John. Allegations that the diaries of Sir John Williams, on which Tony Williams based his research, were altered in any case cast doubt on the whole of this theory.[67]

Writer Mark Daniel proposed that Kelly's murderer was a religious maniac, who killed Kelly as part of a ritual sacrifice, and that the fire in the grate was not to provide light but was used to make a burnt offering.[68] William Stewart proposed in 1939 that Kelly was killed by a deranged midwife, dubbed "Jill the Ripper", whom Kelly had engaged to perform an abortion. According to Stewart, the murderer burnt her own clothes in the grate because they were bloodstained and made her escape wearing Kelly's clothes. This, he suggested, was why Mrs Maxwell had claimed to see Kelly the morning after the murder—she had seen the killer dressed in Kelly's clothes instead.[69] However, the medical reports, which were not available when Stewart constructed his theory, make no mention of a pregnancy, and the theory is entirely based on speculation.

A small minority of modern authors[who?] consider it possible that Kelly was not a victim of the same killer as the other Whitechapel murders. At an assumed age of around 25, she was considerably younger than the other canonical victims, all of whom were in their 40s. The mutilations inflicted on Kelly were far more extensive than those on other victims, but she was also the only one killed in the privacy of a room instead of outdoors. Her murder was separated by five weeks from the previous killings.[70]

There was a delay in the police entering her room after Bowyer had reported the murder. The police waited until about 12.45—two hours after Bowyer's discovery—before entering the room. Sir Charles Warren, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, had been considering using bloodhounds to try to track the killer and did not want anyone disturbing the scene of any suspected Ripper crime until sniffer dogs could be brought to the scene.[71]

In popular culture

Mary Jane Kelly was portrayed by Edina Ronay in the 1965 film A Study in Terror, by Susan Clark in the 1979 film Murder by Decree, by Lysette Anthony in the 1988 TV film Jack the Ripper, by Heather Graham in the 2001 feature film From Hell, and by Katie Jarvis in the 2015 short film Ginger.

The Michaelmas Girls (1975) by John Brooks Barry features Mary Jane Kelly as a lesbian prostitute who conspires with an impotent male sadist to murder fellow streetwalkers.[72] Kelly appears as a supporting character in Kim Newman's 1992 novel Anno Dracula, in which she has been turned into a vampire by Lucy Westenra, making her a target for the vampire-slaying Ripper. Back to Whitechapel is a historical detective novel written by French author Michel Moatti in 2013 that is based on the story of Jack the Ripper and centered on Mary Kelly's fictitious daughter, Amelia Pritlowe.[73]

References

- ^ a b Fido, p. 87

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177; Fido, p. 84

- ^ a b Barnett's statement, 9 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner, p. 364

- ^ a b Evans and Skinner, p. 368

- ^ Evans and Skinner, p. 344

- ^ Philip Sugden, "The Complete History of Jack the Ripper", p.310

- ^ "Mary Jane Kelly". East End Women's Museum. 19 July 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ^ "Casebook: Jack the Ripper – Timeline – Mary Jane Kelly". casebook.org.

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177; Evans and Skinner, pp. 368–369; Fido, p. 85

- ^ "Murder of Mary Jane Kelly: The Ripper's Most Ghastly Killing". Whitechapel Jack. 24 October 2014.

- ^ Rubenhold, Hallie (2019). The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ Begg, p. 267

- ^ Evans and Skinner, p. 336

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177; Evans and Skinner, p. 369; Fido, p. 85

- ^ Evans and Skinner, p. 371

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177; Fido, p. 85

- ^ Fido, pp. 87–88

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 175; Evans and Skinner, p. 368

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177; Fido, p. 88

- ^ Marriott, p. 259

- ^ Cox's statement, 9 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner, pp. 364–365; Fido, p. 87

- ^ Evans and Skinner, p. 371; Fido, pp. 88–89

- ^ Fido, p. 89

- ^ Cullen, p. 180; Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 190–192; Evans and Skinner, pp. 376–377; Fido, p. 96; Marriott, p. 263

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 190–191; Fido, pp. 89–90

- ^ Cook, pp. 173–174; Fido, p. 90

- ^ a b Evans and Rumbelow, p. 193

- ^ Cook, p. 175; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 193

- ^ Fido, p. 116

- ^ Cook, p. 176

- ^ Marriott, p. 263

- ^ Cox's statement, 9 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner, pp. 364–365; Cook, p. 173; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 179; Fido, p. 90

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 179–180; Evans and Skinner, pp. 365–366

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 179–180; Evans and Skinner, p. 371

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 179; Evans and Skinner, p. 371; Marriott, p. 169

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 180; Fido, p. 91

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 181; Evans and Skinner, p. 337

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 181–182; Fido, p. 92

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 190

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 182; Evans and Skinner, p. 372

- ^ a b Evans and Rumbelow, p. 182

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 182–183; Fido, p. 94

- ^ Fido, pp. 93–94

- ^ Inspector Abberline's inquest testimony, 12 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Rumbelow, p. 185; Evans and Skinner, pp. 375–376 and Marriott, p. 177; Fido, p. 95

- ^ Daily Telegraph, 10 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner, p. 338; Marriott, p. 179; Whitehead and Rivett, p. 86

- ^ a b Fido, p. 94

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 188

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 188; Fido, p. 94

- ^ Bond's report, MEPO 3/3153 ff. 10–18, quoted in Evans and Skinner, pp. 345–347 and Marriott, pp. 170–172

- ^ Dr. Phillips' inquest testimony, 12 November 1888, quoted in Marriott, p. 176

- ^ Bond's report, HO 144/221/A49301C, ff. 220–223, quoted in Evans and Skinner, pp. 360–361

- ^ Wilson and Odell, p. 62

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 175, 189; Fido, p. 95; Rumbelow, pp. 94 ff.

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 177; Marriott, p. 172

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ^ The Daily Telegraph, 19 November 1888, page 3; 20 November 1888, page 3

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, p. 186

- ^ Letter from Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, 10 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner, pp. 360–362 and Rumbelow, pp. 145–147

- ^ Evans and Skinner, pp. 347–349

- ^ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 203–204

- ^ Davenport-Hines, Richard (2004). "Jack the Ripper (fl. 1888)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Subscription required for online version.

- ^ a b Rumbelow, p. 262; Whitehead and Rivett, pp. 122–123

- ^ Rumbelow, p. 262

- ^ Marriott, p. 259; Rumbelow, p. 262

- ^ Whitehead and Rivett, p. 123

- ^ Marriott, pp. 167–180

- ^ Pegg, Jennifer (October 2005). "Uncle Jack Under the Microscope". Ripper Notes issue #24. Inklings Press. ISBN 0-9759129-5-X.

* Pegg, Jennifer (January 2006). "'Shocked and Dismayed': An Update on the Uncle Jack Controversy". Ripper Notes issue #25, pp. 54–61. Inklings Press. ISBN 0-9759129-6-8 - ^ Quoted in Roland, Paul (2006) The Crimes of Jack the Ripper, London: Arcturus Publishing, ISBN 978-0-572-03285-2, pp. 105–107

- ^ Stewart, William (1939) Jack the Ripper: A New Theory, Toronto: Saunders, quoted in Wilson and Odell, pp. 142–145

- ^ The Murder Almanac ISBN 978-1-897-78404-4 p. 91

- ^ "Casebook: Jack the Ripper – Mary Jane Kelly". casebook.org.

- ^ Wilson and Odell, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Malaure, Julie (6 March 2013). "Londres : sur la piste de Jack l'Éventreur". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 22 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Begg, Paul (2006). Jack the Ripper: The Facts. Anova Books. ISBN 1-86105-687-7

- Cullen, Tom (1965). Autumn of Terror. London: The Bodley Head.

- Evans, Stewart P.; Rumbelow, Donald (2006). Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-4228-2

- Evans, Stewart P.; Skinner, Keith (2000). The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. London: Constable and Robinson. ISBN 1-84119-225-2

- Fido, Martin (1987), The Crimes, Detection and Death of Jack the Ripper, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-79136-2

- Marriott, Trevor (2005). Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation. London: John Blake. ISBN 1-84454-103-7

- Rumbelow, Donald (2004). The Complete Jack the Ripper: Fully Revised and Updated. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-017395-1

- Scott, Christopher (2005). Will the Real Mary Kelly...?. London: Publish and be Damned. ISBN 978-1-90527-705-6

- Whitehead, Mark; Rivett, Miriam (2006). Jack the Ripper. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-69-5

- Wilson, Colin; Odell, Robin (1987) Jack the Ripper: Summing Up and Verdict. Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-01020-5