Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton | |

|---|---|

1792 portrait of Matthew Boulton | |

| Born | 3 September 1728 Birmingham, England |

| Died | 17 August 1809 (aged 80) Birmingham, England |

| Occupation | Manufacturer |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Robinson (d. 1759), Anne Robinson |

| Children | Three daughters who died in infancy, Anne Boulton, Matthew Robinson Boulton |

| Parent(s) | Matthew Boulton, Christiana Boulton née Piers |

| Relatives | Matthew Piers Watt Boulton (grandson) |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society (1785), High Sheriff of Staffordshire (1794) |

Matthew Boulton FRS (/ˈboʊltən/; 3 September 1728 – 17 August 1809) was an English manufacturer and business partner of Scottish engineer James Watt. In the final quarter of the 18th century, the partnership installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engines, which were a great advance on the state of the art, making possible the mechanisation of factories and mills. Boulton applied modern techniques to the minting of coins, striking millions of pieces for Britain and other countries, and supplying the Royal Mint with up-to-date equipment.

Born in Birmingham, he was the son of a Birmingham manufacturer of small metal products who died when Boulton was 31. By then Boulton had managed the business for several years, and thereafter expanded it considerably, consolidating operations at the Soho Manufactory, built by him near Birmingham. At Soho, he adopted the latest techniques, branching into silver plate, ormolu and other decorative arts. He became associated with James Watt when Watt's business partner, John Roebuck, was unable to pay a debt to Boulton, who accepted Roebuck's share of Watt's patent as settlement. He then successfully lobbied Parliament to extend Watt's patent for an additional 17 years, enabling the firm to market Watt's steam engine. The firm installed hundreds of Boulton & Watt steam engines in Britain and abroad, initially in mines and then in factories.

Boulton was a key member of the Lunar Society, a group of Birmingham-area men prominent in the arts, sciences, and theology. Members included Watt, Erasmus Darwin, Josiah Wedgwood and Joseph Priestley. The Society met each month near the full moon. Members of the Society have been given credit for developing concepts and techniques in science, agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and transport that laid the groundwork for the Industrial Revolution.

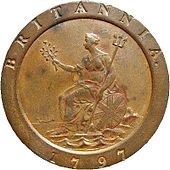

Boulton founded the Soho Mint, to which he soon adapted steam power. He sought to improve the poor state of Britain's coinage, and after several years of effort obtained a contract in 1797 to produce the first British copper coinage in a quarter century. His "cartwheel" pieces were well-designed and difficult to counterfeit, and included the first striking of the large copper British penny, which continued to be coined until decimalisation in 1971. He retired in 1800, though continuing to run his mint, and died in 1809. His image appears alongside James Watt on the Bank of England's new Series F £50 note.

Background

Birmingham had long been a centre of the ironworking industry. In the early 18th century the town entered a period of expansion as iron working became easier and cheaper with the transition (beginning in 1709) from charcoal to coke as a means of smelting iron.[1] Scarcity of wood in increasingly deforested England and discoveries of large quantities of coal in Birmingham's county of Warwickshire and the adjacent county of Staffordshire speeded the transition.[1] Much of the iron was forged in small foundries near Birmingham, especially in the Black Country, including nearby towns such as Smethwick and West Bromwich. The resultant thin iron sheets were transported to factories in and around Birmingham.[1] With the town far from the sea and great rivers and with canals not yet built, metalworkers concentrated on producing small, relatively valuable pieces, especially buttons and buckles.[1] Frenchman Alexander Missen wrote that while he had seen excellent cane heads, snuff boxes and other metal objects in Milan, "the same can be had cheaper and better in Birmingham".[1] These small objects came to be known as "toys", and their manufacturers as "toymakers".[2]

Boulton was a descendant of families from around Lichfield, his great-great-great-great grandfather, Rev. Zachary Babington, having been Chancellor of Lichfield.[3] Boulton's father, also named Matthew and born in 1700, moved to Birmingham from Lichfield to serve an apprenticeship, and in 1723 he married Christiana Piers.[4] The elder Boulton was a toymaker with a small workshop specialising in buckles.[5] Matthew Boulton was born in 1728, their third child and the second of that name, the first Matthew having died at the age of two in 1726.[6]

Early and family life

The elder Boulton's business prospered after young Matthew's birth, and the family moved to the Snow Hill area of Birmingham, then a well-to-do neighbourhood of new houses. As the local grammar school was in disrepair Boulton was sent to an academy in Deritend, on the other side of Birmingham.[7] At the age of 15 he left school, and by 17 he had invented a technique for inlaying enamels in buckles that proved so popular that the buckles were exported to France, then reimported to Britain and billed as the latest French developments.[8]

On 3 March 1749 Boulton married Mary Robinson, a distant cousin and the daughter of a successful mercer, and wealthy in her own right. They lived briefly with the bride's mother in Lichfield, and then moved to Birmingham where the elder Matthew Boulton made his son a partner at the age of 21.[8] Though the son signed business letters "from father and self", by the mid-1750s he was effectively running the business. The elder Boulton retired in 1757 and died in 1759.[9]

The Boultons had three daughters in the early 1750s, but all died in infancy.[10] Mary Boulton's health deteriorated, and she died in August 1759.[10] Not long after her death Boulton began to woo her sister Anne. Marriage with a deceased wife's sister was forbidden by ecclesiastical law, though permitted by common law. Nonetheless, they married on 25 June 1760 at St. Mary's Church, Rotherhithe.[11] Eric Delieb, who wrote a book on Boulton's silver, with a biographical sketch, suggests that the marriage celebrant, Rev. James Penfold, an impoverished curate, was probably bribed.[12] Boulton later advised another man who was seeking to wed his late wife's sister: "I advise you to say nothing of your intentions but to go quickly and snugly to Scotland or some obscure corner of London, suppose Wapping, and there take lodgings to make yourself a parishioner. When the month is expired and the Law fulfilled, live and be happy ... I recommend silence, secrecy, and Scotland."[13]

The union was opposed by Anne's brother Luke, who feared Boulton would control (and possibly dissipate) much of the Robinson family fortune. In 1764 Luke Robinson died, and his estate passed to his sister Anne and thus into Matthew Boulton's control.[14]

The Boultons had two children, Matthew Robinson Boulton and Anne Boulton.[15] Matthew Robinson in turn had six children with two wives. His eldest son Matthew Piers Watt Boulton, broadly educated and also a man of science,[16] gained some fame posthumously for his invention of the important aeronautical flight control, the aileron.[17] As his father before him, he also had two wives and six children.[18]

Innovator

Expansion of the business

After the death of his father in 1759, Boulton took full control of the family toymaking business. He spent much of his time in London and elsewhere, promoting his wares. He arranged for a friend to present a sword to Prince Edward, and the gift so interested the Prince's older brother, George, Prince of Wales, the future King George III, that he ordered one for himself.[19]

With capital accumulated from his two marriages and his inheritance from his father, Boulton sought a larger site to expand his business. In 1761 he leased 13 acres (5.3 ha) at Soho, then just in Staffordshire, with a residence, Soho House, and a rolling mill.[20] Soho House was at first occupied by Boulton relatives, and then by his first partner, John Fothergill. In 1766 Boulton required Fothergill to vacate Soho House, and lived there himself with his family. Both husband and wife died there, Anne Boulton of an apparent stroke in 1783[21] and her husband after a long illness in 1809.[20]

The 13 acres (5 ha) at Soho included common land that Boulton enclosed, later decrying what he saw as the "idle beggarly" condition of the people who had used it.[22] By 1765 his Soho Manufactory had been erected. The warehouse, or "principal building", had a Palladian front and 19 bays for loading and unloading, and had quarters for clerks and managers on the upper storeys. The structure was designed by local architect William Wyatt at a time when industrial buildings were commonly designed by engineers.[23] Other buildings contained workshops. Boulton and Fothergill invested in the most advanced metalworking equipment, and the complex was admired as a modern industrial marvel.[24] Although the cost of the principal building alone had been estimated at £2,000[24] (about £276,000 today);[25] the final cost was five times that amount.[24] The partnership spent over £20,000 in building and equipping the premises.[26] The partners' means were not equal to the total costs, which were met only by heavy borrowing and by artful management of creditors.[24]

Among the products Boulton sought to make in his new facility were sterling silver plate for those able to afford it, and Sheffield plate, silver-plated copper, for those less well off. Boulton and his father had long made small silver items, but there is no record of large items in either silver or Sheffield plate being made in Birmingham before Boulton did so.[27] To make items such as candlesticks more cheaply than the London competition, the firm made many items out of thin, die-stamped sections, which were shaped and joined together.[27] One impediment to Boulton's work was the lack of an assay office in Birmingham. The silver toys long made by the family firm were generally too light to require assaying, but silver plate had to be sent over 70 miles (110 km) to the nearest assay office, at Chester, to be assayed and hallmarked, with the attendant risks of damage and loss. Alternatively they could be sent to London, but this exposed them to the risk of being copied by competitors.[28] Boulton wrote in 1771, "I am very desirous of becoming a great silversmith, yet I am determined not to take up that branch in the large way I intended, unless powers can be obtained to have a marking hall [assay office] at Birmingham."[29] Boulton petitioned Parliament for the establishment of an assay office in Birmingham. Though the petition was bitterly opposed by London goldsmiths, he was successful in getting Parliament to pass an act establishing assay offices in Birmingham and Sheffield, whose silversmiths had faced similar difficulties in transporting their wares.[30] The silver business proved not to be profitable due to the opportunity cost of keeping a large amount of capital tied up in the inventory of silver.[31] The firm continued to make large quantities of Sheffield plate, but Boulton delegated responsibility for this enterprise to trusted subordinates, involving himself little in it.[32]

As part of Boulton's efforts to market to the wealthy, he started to sell vases decorated with ormolu, previously a French speciality. Ormolu was milled gold (from the French or moulu) amalgamated with mercury, and applied to the item, which was then heated to drive off the mercury, leaving the gold decoration.[33] In the late 1760s and early 1770s there was a fashion among the wealthy for decorated vases, and he sought to cater to this craze. He initially ordered ceramic vases from his friend and fellow Lunar Society member Josiah Wedgwood, but ceramic proved unable to bear the weight of the decorations and Boulton chose marble and other decorative stone as the material for his vases.[34] Boulton copied vase designs from classical Greek works and borrowed works of art from collectors, merchants, and sculptors.[34]

Fothergill and others searched Europe for designs for these creations.[35] In March 1770 Boulton visited the Royal Family and sold several vases to Queen Charlotte, George III's wife.[36] He ran annual sales at Christie's in 1771 and 1772. The Christie's exhibition succeeded in publicising Boulton and his products, which were highly praised, but the sales were not financially successful with many works left unsold or sold below cost.[37] When the craze for vases ended in the early 1770s, the partnership was left with a large stock on its hands, and disposed of much of it in a single massive sale to Catherine the Great of Russia[38]—the Empress described the vases as superior to French ormolu, and cheaper as well.[39] Boulton continued to solicit orders, though "ormolu" was dropped from the firm's business description from 1779, and when the Boulton-Fothergill partnership was dissolved by the latter's 1782 death there were only 14 items of ormolu in the "toy room".[40]

Among Boulton's most successful products were mounts for small Wedgwood products such as plaques, cameo brooches and buttons in the distinctive ceramics, notably jasper ware, for which Wedgwood's firm remains well known. The mounts of these articles, many of which have survived, were made of ormolu or cut steel, which had a jewel-like gleam.[41] Boulton and Wedgwood were friends, alternately co-operating and competing, and Wedgwood wrote of Boulton, "It doubles my courage to have the first Manufacturer in England to encounter with—The match likes me well—I like the Man, I like his spirit."[41]

In the 1770s Boulton introduced an insurance system for his workers that served as the model for later schemes, allowing his workers compensation in the event of injury or illness.[42] The first of its kind in any large establishment, employees paid one-sixtieth of their wages into the Soho Friendly Society, membership in which was mandatory.[43] The firm's apprentices were poor or orphaned boys, trainable into skilled workmen; he declined to hire the sons of gentlemen as apprentices, stating that they would be "out of place" among the poorer boys.[44]

Not all of Boulton's innovations proved successful. Together with painter Francis Eginton,[a] he created a process for the mechanical reproduction of paintings for middle-class homes, but eventually abandoned the procedure.[45] Boulton and James Keir produced an alloy called "Eldorado metal" that they claimed would not corrode in water and could be used for sheathing wooden ships. After sea trials the Admiralty rejected their claims, and the metal was used for fanlights and sash windows at Soho House.[46] Boulton feared that construction of a nearby canal would damage his water supply, but this did not prove to be the case, and in 1779 he wrote, "Our navigation goes on prosperously; the junction with the Wolverhampton Canal is complete, and we already sail to Bristol and to Hull."[47]

- Products of Boulton's manufactory

-

Ormolu tea urn by Boulton & Fothergill

-

Boulton & Fothergill Sheffield plate beer tankard, late 1760s

Partnership with Watt

Boulton's Soho site proved to have insufficient hydropower for his needs, especially in the summer when the millstream's flow was greatly reduced. He realised that using a steam engine either to pump water back up to the millpond or to drive equipment directly would help to provide the necessary power.[48] He began to correspond with Watt in 1766, and first met him two years later. In 1769 Watt patented an engine with the innovation of a separate condenser, making it far more efficient than earlier engines. Boulton realised not only that this engine could power his manufactory, but also that its production might be a profitable business venture.[49]

After receiving the patent, Watt did little to develop the engine into a marketable invention, turning to other work. In 1772, Watt's partner, Dr. John Roebuck, ran into financial difficulties, and Boulton, to whom he owed £1,200, accepted his two-thirds share in Watt's patent as satisfaction of the debt. Boulton's partner Fothergill refused to have any part in the speculation, and accepted cash for his share.[49] Boulton's share was worth little without Watt's efforts to improve his invention.[50] At the time, the principal use of steam engines was to pump water out of mines. The engine commonly in use was the Newcomen steam engine, which consumed large amounts of coal and, as mines became deeper, proved incapable of keeping them clear of water.[51] Watt's work was well known, and a number of mines that needed engines put off purchasing them in the hope that Watt would soon market his invention.[52]

Boulton boasted about Watt's talents, leading to an employment offer from the Russian government, which Boulton had to persuade Watt to turn down.[53] In 1774 he was able to convince Watt to move to Birmingham, and they entered into a partnership the following year.[54] By 1775 six of the 14 years of Watt's original patent had elapsed,[51] but thanks to Boulton's lobbying Parliament passed an act extending Watt's patent until 1800.[49] Boulton and Watt began work improving the engine. With the assistance of iron master John Wilkinson (brother-in-law of Lunar Society member Joseph Priestley), they succeeded in making the engine commercially viable.[54]

In 1776 the partnership erected two engines, one for Wilkinson and one at a mine in Tipton in the Black Country. Both engines were successfully installed, leading to favourable publicity for the partnership.[55] Boulton and Watt began to install engines elsewhere. The firm rarely produced the engine itself: it had the purchaser buy parts from a number of suppliers and then assembled the engine on-site under the supervision of a Soho engineer. The company made its profit by comparing the amount of coal used by the machine with that used by an earlier, less efficient Newcomen engine, and required payments of one-third of the savings annually for the next 25 years.[56] This pricing scheme led to disputes, as many mines fuelled the engines using coal of unmarketable quality that cost the mine owners only the expense of extraction.[56] Mine owners were also reluctant to make the annual payments, viewing the engines as theirs once erected, and threatened to petition Parliament to repeal Watt's patent.[57]

The county of Cornwall was a major market for the firm's engines. It was mineral-rich and had many mines. However, the special problems for mining there, including local rivalries and high prices for coal, which had to be imported from Wales, forced Watt[58] and later Boulton to spend several months a year in Cornwall overseeing installations and resolving problems with the mineowners.[59] In 1779 the firm hired engineer William Murdoch,[b] who was able to take over the management of most of the on-site installation problems, allowing Watt and Boulton to remain in Birmingham.[56]

The pumping engine for use in mines was a great success. In 1782 the firm sought to modify Watt's invention so that the engine had a rotary motion, making it suitable for use in mills and factories. On a 1781 visit to Wales Boulton had seen a powerful copper-rolling mill driven by water, and when told it was often inoperable in the summer due to drought suggested that a steam engine would remedy that defect. Boulton wrote to Watt urging the modification of the engine, warning that they were reaching the limits of the pumping engine market: "There is no other Cornwall to be found, and the most likely line for increasing the consumption of our engines is the application of them to mills, which is certainly an extensive field."[60] Watt spent much of 1782 on the modification project, and though he was concerned that few orders would result, completed it at the end of the year.[61] One order was received in 1782, and several others from mills and breweries soon after.[62] George III toured the Whitbread brewery in London, and was impressed by the engine.[63] As a demonstration, Boulton used two engines to grind wheat at the rate of 150 bushels per hour in his new Albion Mill in London.[63] While the mill was not financially successful,[64] according to historian Jenny Uglow it served as a "publicity stunt par excellence" for the firm's latest innovation.[63] Before its 1791 destruction by fire, the mill's fame, according to early historian Samuel Smiles, "spread far and wide", and orders for rotative engines poured in not only from Britain but from the United States and the West Indies.[65]

Between 1775 and 1800 the firm produced approximately 450 engines. It did not let other manufacturers produce engines with separate condensers, and approximately 1,000 Newcomen engines, less efficient but cheaper and not subject to the restrictions of Watt's patent, were produced in Britain during that time.[66] Boulton boasted to James Boswell when the diarist toured Soho, "I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—POWER."[67] The development of an efficient steam engine allowed large-scale industry to be developed,[68] and the industrial city, such as Manchester became, to exist.[69]

Involvement with coinage

By 1786, two-thirds of the coins in circulation in Britain were counterfeit, and the Royal Mint responded by shutting itself down, worsening the situation.[70] Few of the silver coins being passed were genuine.[71] Even the copper coins were melted down and replaced with lightweight fakes.[71] The Royal Mint struck no copper coins for 48 years, from 1773 until 1821.[72] The resultant gap was filled with copper tokens that approximated the size of the halfpenny, struck on behalf of merchants. Boulton struck millions of these merchant pieces.[73] On the rare occasions when the Royal Mint did strike coins, they were relatively crude, with quality control nonexistent.[70]

Boulton had turned his attention to coinage in the mid-1780s; they were just another small metal product like those he manufactured.[70] He also had shares in several Cornish copper mines, and had a large personal stock of copper, purchased when the mines were unable to dispose of it elsewhere.[74] However, when orders for counterfeit money were sent to him, he refused them: "I will do anything, short of being a common informer against particular persons, to stop the malpractices of the Birmingham coiners."[47] In 1788 he established the Soho Mint as part of his industrial plant. The mint included eight steam-driven presses, each striking between 70 and 84 coins per minute. The firm had little immediate success getting a licence to strike British coins, but was soon engaged in striking coins for the British East India Company for use in India.[70]

The coin crisis in Britain continued. In a letter to the Master of the Mint, Lord Hawkesbury (whose son would become Prime Minister as Earl of Liverpool) on 14 April 1789, Boulton wrote:

In the course of my journeys, I observe that I receive upon an average two-thirds counterfeit halfpence for change at toll-gates, etc. and I believe the evil is daily increasing, as the spurious money is carried into circulation by the lowest class of manufacturers, who pay with it the principal part of the wages of the poor people they employ. They purchase from the subterraneous coiners 36 shillings'-worth of copper (in nominal value) for 20 shillings, so that the profit derived from the cheating is very large.[74]

Boulton offered to strike new coins at a cost "not exceeding half the expense which the common copper coin hath always cost at his Majesty's Mint".[75] He wrote to his friend, Sir Joseph Banks, describing the advantages of his coinage presses:

It will coin much faster, with greater ease, with fewer persons, for less expense, and more beautiful than any other machinery ever used for coining ... Can lay the pieces or blanks upon the die quite true and without care or practice and as fast as wanted. Can work night and day without fatigue by two setts of boys. The machine keeps an account of the number of pieces struck which cannot be altered from the truth by any of the persons employed. The apparatus strikes an inscription upon the edge with the same blow that strikes the two faces. It strikes the [back]ground[c] of the pieces brighter than any other coining press can do. It strikes the pieces perfectly round, all of equal diameter, and exactly concentric with the edge, which cannot be done by any other machinery now in use.[76]

Boulton spent much time in London lobbying for a contract to strike British coins, but in June 1790 the Pitt Government postponed a decision on recoinage indefinitely.[77] Meanwhile, the Soho Mint struck coins for the East India Company, Sierra Leone and Russia, while producing high-quality planchets, or blank coins, to be struck by national mints elsewhere.[70] The firm sent over 20 million blanks to Philadelphia, to be struck into cents and half-cents by the United States Mint[78]—Mint Director Elias Boudinot found them to be "perfect and beautifully polished".[70] The high-technology Soho Mint gained increasing and somewhat unwelcome attention: rivals attempted industrial espionage, while lobbying for Boulton's mint to be shut down.[70]

The national financial crisis reached its nadir in February 1797, when the Bank of England stopped redeeming its bills for gold. In an effort to get more money into circulation, the Government adopted a plan to issue large quantities of copper coins, and Lord Hawkesbury summoned Boulton to London on 3 March 1797, informing him of the Government's plan. Four days later, Boulton attended a meeting of the Privy Council, and was awarded a contract at the end of the month.[78] According to a proclamation dated 26 July 1797, King George III was "graciously pleased to give directions that measures might be taken for an immediate supply of such copper coinage as might be best adapted to the payment of the laborious poor in the present exigency ... which should go and pass for one penny and two pennies".[79] The proclamation required that the coins weigh one and two ounces respectively, bringing the intrinsic value of the coins close to their face value.[79] Boulton made efforts to frustrate counterfeiters. Designed by Heinrich Küchler, the coins featured a raised rim with incuse or sunken letters and numbers, features difficult for counterfeiters to match.[70] The twopenny coins measured exactly an inch and a half across; 16 pennies lined up would reach two feet.[70] The exact measurements and weights made it easy to detect lightweight counterfeits. Küchler also designed proportionate halfpennies and farthings; these were not authorised by the proclamation, and though pattern pieces were struck, they never officially entered circulation. The halfpenny measured ten to a foot, the farthing 12 to a foot.[70] The coins were nicknamed "cartwheels", both because of the size of the twopenny coin and in reference to the broad rims of both denominations.[80] The penny was the first of its denomination to be struck in copper.[81]

The cartwheel twopenny coin was not struck again; much of the mintage was melted down in 1800 when the price of copper increased[71] and it had proved too heavy for commerce and was difficult to strike.[82] Much to Boulton's chagrin, the new coins were being counterfeited in copper-covered lead within a month of issuance.[83] Boulton was awarded additional contracts in 1799 and 1806, each for the lower three copper denominations. Though the cartwheel design was used again for the 1799 penny (struck with the date 1797), all other strikings used lighter planchets to reflect the rise in the price of copper, and featured more conventional designs.[78][84] Boulton greatly reduced the counterfeiting problem by adding lines to the coin edges, and striking slightly concave planchets.[85] Counterfeiters turned their sights to easier targets, the pre-Soho pieces, which were not withdrawn, due to the expense, until a gradual withdrawal took place between 1814 and 1817.[86]

Watt, in his eulogy after Boulton's death in 1809, stated:

In short, had Mr. Boulton done nothing more in the world than he has accomplished in improving the coinage, his name would deserve to be immortalised; and if it be considered that this was done in the midst of various other important avocations, and at enormous expense,— for which, at the time, he could have had no certainty of an adequate return,—we shall be at a loss whether most to admire his ingenuity, his perseverance, or his munificence. He has conducted the whole more like a sovereign than a private manufacturer; and the love of fame has always been to him a greater stimulus than the love of gain. Yet it is to be hoped that, even in the latter point of view, the enterprise answered its purpose.[74]

Activities and views

Scientific studies and the Lunar Society

Boulton never had any formal schooling in science. His associate and fellow Lunar Society member James Keir eulogised him after his death:

Mr. [Boulton] is proof of how much scientific knowledge may be acquired without much regular study, by means of a quick & just apprehension, much practical application, and nice mechanical feelings. He had very correct notions of the several branches of natural philosophy, was master of every metallic art & possessed all the chemistry that had any relations to the object of his various manufactures. Electricity and astronomy were at one time among his favourite amusements.[87]

From an early age, Boulton had interested himself in the scientific advances of his times. He discarded theories that electricity was a manifestation of the human soul, writing "we know tis matter & tis wrong to call it Spirit".[88] He called such theories "Cymeras [chimeras] of each others Brain".[88] His interest brought him into contact with other enthusiasts such as John Whitehurst, who also became a member of the Lunar Society.[89] In 1758 the Pennsylvania printer Benjamin Franklin, the leading experimenter in electricity, journeyed to Birmingham during one of his lengthy stays in Britain; Boulton met him, and introduced him to his friends.[90] Boulton worked with Franklin in efforts to contain electricity within a Leyden jar, and when the printer needed new glass for his "glassychord" (a mechanised version of musical glasses) he obtained it from Boulton.[91]

Despite time constraints imposed on him by the expansion of his business, Boulton continued his "philosophical" work (as scientific experimentation was then called).[90] He wrote in his notebooks observations on the freezing and boiling point of mercury, on people's pulse rates at different ages, on the movements of the planets, and on how to make sealing wax and disappearing ink.[92] However, Erasmus Darwin, another fellow enthusiast who became a member of the Lunar Society, wrote to him in 1763, "As you are now become a sober plodding Man of Business, I scarcely dare trouble you to do me a favour in the ... philosophical way."[93]

The Birmingham enthusiasts, including Boulton, Whitehurst, Keir, Darwin, Watt (after his move to Birmingham), potter Josiah Wedgwood and clergyman and chemist Joseph Priestley began to meet informally in the late 1750s. This evolved into a monthly meeting near the full moon, providing light to journey home afterwards, a pattern common for clubs in Britain at the time.[87] The group eventually dubbed itself the "Lunar Society", and following the death of member Dr William Small in 1775, who had informally coordinated communication between the members, Boulton took steps to put the Society on a formal footing. They met on Sundays, beginning with dinner at 2 p.m., and continuing with discussions until at least 8.[94]

While not a formal member of the Lunar Society, Sir Joseph Banks was active in it. In 1768 Banks sailed with Captain James Cook to the South Pacific, and took with him green glass earrings made at Soho to give to the natives. In 1776 Captain Cook ordered an instrument from Boulton, most likely for use in navigation. Boulton generally preferred not to take on lengthy projects, and he warned Cook that its completion might take years. In June 1776 Cook left on the voyage on which he was killed almost three years later, and Boulton's records show no further mention of the instrument.[95]

In addition to the scientific discussions and experiments conducted by the group, Boulton had a business relationship with some of the members. Watt and Boulton were partners for a quarter century. Boulton purchased vases from Wedgwood's pottery to be decorated with ormolu, and contemplated a partnership with him.[96] Keir was a long-time supplier and associate of Boulton, though Keir never became his partner as he hoped.[97]

In 1785 both Boulton and Watt were elected as Fellows of the Royal Society. According to Whitehurst, who wrote to congratulate Boulton, not a single vote was cast against him.[2]

Though Boulton hoped his activities for the Lunar Society would "prevent the decline of a Society which I hope will be lasting",[94] as members died or moved away they were not replaced. In 1813, four years after his death, the Society was dissolved and a lottery was held to dispose of its assets. Since there were no minutes of meetings, few details of the gatherings remain.[87] Historian Jenny Uglow wrote of the lasting impact of the Society:

The Lunar Society['s] ... members have been called the fathers of the Industrial Revolution ... [T]he importance of this particular Society stems from its pioneering work in experimental chemistry, physics, engineering, and medicine, combined with leadership in manufacturing and commerce, and with political and social ideals. Its members were brilliant representatives of the informal scientific web which cut across class, blending the inherited skills of craftsmen with the theoretical advances of scholars, a key factor in Britain's leap ahead of the rest of Europe.[87]

Community work

Boulton was widely involved in civic activities in Birmingham. His friend Dr John Ash had long sought to build a hospital in the town. A great fan of the music of Handel, Boulton conceived of the idea to hold a music festival in Birmingham to raise funds for the hospital. The festival took place in September 1768, the first of a series stretching well into the twentieth century.[98] The hospital opened in 1779. Boulton also helped build the General Dispensary, where outpatient treatment could be obtained.[98] A firm supporter of the Dispensary, he served as treasurer, and wrote, "If the funds of the institution are not sufficient for its support, I will make up the deficiency."[99] The Dispensary soon outgrew its original quarters, and a new building in Temple Row was opened in 1808, shortly before Boulton's death.[99]

Boulton helped found the New Street Theatre in 1774, and later wrote that having a theatre encouraged well-to-do visitors to come to Birmingham, and to spend more money than they would have otherwise.[98] Boulton attempted to have the theatre recognised as a patent theatre with a Royal Patent, entitled to present serious drama; he failed in 1779 but succeeded in 1807.[100] He also supported Birmingham's Oratorio Choral Society, and collaborated with button maker and amateur musical promoter Joseph Moore to put on a series of private concerts in 1799. He maintained a pew at St Paul's Church, Birmingham, a centre of musical excellence.[98] When performances of the Messiah were organised at Westminster Abbey in 1784 in the (incorrect) belief it was the centennial of Handel's birth and the (correct) belief that it was the 25th anniversary of his death, Boulton attended and wrote, "I scarcely know which was grandest, the sounds or the scene. Both was transcendibly fine that it is not in my power of words to describe. In the grand Halleluja my soul almost ascended from my body."[101]

Concerned about the level of crime in Birmingham, Boulton complained, "The streets are infested from Noon Day to midnight with prostitutes."[102] In an era prior to the establishment of the police, Boulton served on a committee to organise volunteers to patrol the streets at night and reduce crime. He supported the local militia, providing money for weapons. In 1794 he was elected High Sheriff of Staffordshire, his county of residence.[98]

Besides seeking to improve local life, Boulton took an interest in world affairs. Initially sympathetic to the cause of the rebellious American colonists, Boulton changed his view once he realised that an independent America might be a threat to British trade, and in 1775 organised a petition urging the government to take a hard line with the Americans—though when the revolution proved successful, he resumed trade with the former colonies.[103] He was more sympathetic to the cause of the French Revolution, believing it justified, though he expressed his horror at the bloody excesses of the Revolutionary government.[104] When war with France broke out, he paid for weapons for a company of volunteers, sworn to resist any French invasion.[105]

Family and later life, death, and memorials

When Boulton was widowed in 1783 he was left with the care of his two teenage children. Neither his son Matthew Robinson Boulton nor his daughter Anne enjoyed robust health; the younger Matthew was often ill and was a poor student who was shuttled from school to school until he joined his father's business in 1790; Anne suffered from a diseased leg that prevented her from enjoying a full life.[106] Despite his lengthy absences on business, Boulton cared deeply for his family. He wrote to his wife in January 1780,

Nothing could in the least palliate this long, this cold, this very distant separation from my dearest wife and children but the certain knowledge that I am preparing for their ease, happiness and prosperity, and when that is the prise, I know no hardships that I would not encounter with, to obtain it.[107]

With the expiry of the patent in 1800 both Boulton and Watt retired from the partnership, each turning over his role to his namesake son. The two sons made changes, quickly ending public tours of the Soho Manufactory in which the elder Boulton had taken pride throughout his time in Soho.[108] In retirement Boulton remained active, continuing to run the Soho Mint. When a new Royal Mint was built on Tower Hill in 1805, Boulton was awarded the contract to equip it with modern machinery.[109] His continued activity distressed Watt, who had entirely retired from Soho, and who wrote to Boulton in 1804, "[Y]our friends fear much that your necessary attention to the operation of the coinage may injure your health".[110]

Boulton helped deal with the shortage of silver, persuading the Government to let him overstrike the Bank of England's large stock of Spanish dollars with an English design. The Bank had attempted to circulate the dollars by countermarking the coins on the side showing the Spanish king with a small image of George III, but the public was reluctant to accept them, in part due to counterfeiting.[111] This attempt inspired the couplet, "The Bank to make their Spanish Dollars pass/Stamped the head of a fool on the neck of an ass."[111] Boulton obliterated the old design in his restriking.[111] Though Boulton was not as successful in defeating counterfeiters as he hoped (high quality fakes arrived at the Bank's offices within days of the issuance),[112] these coins circulated until the Royal Mint again struck large quantities of silver coin in 1816, when Boulton's were withdrawn. He oversaw the final issue of his coppers for Britain in 1806, and a major issue of coppers to circulate only in Ireland.[113] Even as his health failed, he had his servants carry him from Soho House to the Soho Mint, and he sat and watched the machinery,[114]which was kept exceptionally busy in 1808 by the striking of almost 90,000,000 pieces for the East India Company.[78] He wrote, "Of all the mechanical subjects I ever entered upon, there is none in which I ever engaged with so much ardour as that of bringing to perfection the art of coining."[114]

By early 1809 he was seriously ill.[108] He had long suffered from kidney stones, which also lodged in the bladder, causing him great pain.[115] He died at Soho House on 17 August 1809.[108] He was buried in the graveyard of St. Mary's Church, Handsworth, in Birmingham – the church was later extended over the site of his grave. Inside the church, on the north wall of the sanctuary, is a large marble monument to him, commissioned by his son, sculpted by the sculptor John Flaxman.[116] It includes a marble bust of Boulton, set in a circular opening above two putti, one holding an engraving of the Soho Manufactory.[116]

Boulton is recognised by several memorials and other commemorations in and around Birmingham. Soho House, his home from 1766 until his death, is now a museum,[117] as is his first workshop, Sarehole Mill.[118] The Soho archives are at the Birmingham City Archives.[42] He is recognised by blue plaques at his Steelhouse Lane birthplace and at Soho House.[119] A gilded bronze statue of Boulton, Watt and Murdoch (1956) by William Bloye stands outside the old Register Office on Broad Street in central Birmingham.[120] Matthew Boulton College was named in his honour in 1957.[121] The two-hundredth anniversary of his death, in 2009, resulted in a number of tributes. Birmingham City Council promoted "a year long festival celebrating the life, work and legacy of Matthew Boulton".[122]

On 29 May 2009 the Bank of England announced that Boulton and Watt would appear on a new £50 note. The design is the first to feature a dual portrait on a Bank of England note, and presents the two industrialists side by side with images of a steam engine and Boulton's Soho Manufactory. Quotes attributed to each of the men are inscribed on the note: "I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—POWER" (Boulton) and "I can think of nothing else but this machine" (Watt).[123] In September 2011 it was announced that the notes would enter circulation on 2 November.[124]

In March 2009, Boulton was honoured with the issue of a Royal Mail postage stamp.[125]

On 17 October 2014 a memorial to him was unveiled in Westminster Abbey beside that of his business partner James Watt.

Notes

Explanatory notes

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Uglow 2002, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b McLean 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Mason 2009, unnumbered, two pages before page 1.

- ^ McLean 2009, p. 1, Uglow gives the wedding date as 1724.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 23.

- ^ a b Uglow 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 57.

- ^ a b Uglow 2002, p. 60.

- ^ Uglow 2002, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Delieb 1971, p. 19.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 174.

- ^ Kinzer, Bruce (1 May 2009). "Flying Under The Radar: The Strange Case Of Matthew Piers Watt Boulton". Times Literary Supplement. pp. 14–15.

- ^

Crouch, Tom (September 2009), "Oldies and Oddities: Where Do Ailerons Come From?", Air & Space magazine

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|periodical=(help) - ^ Barker, Stephen Daniel (ed.) Genealogy Data Page 3 (Family Pages), PeterBarker.plus.com website, retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 61.

- ^ a b Mason 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 368.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Loggie 2009, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Uglow 2002, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Purchasing Power of British Pounds 1264–2008, MeasuringWorth, retrieved 22 June 2009 (RPI equivalents)

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 169.

- ^ a b Quickenden 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 202.

- ^ Baggott 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Baggott 2009, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 170.

- ^ Quickenden 2009, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 194.

- ^ a b Goodison 2009, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 172.

- ^ Goodison 2009, p. 59.

- ^ Goodison 2009, p. 61.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 201.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 174.

- ^ Goodison 2009, p. 62.

- ^ a b The Wedgwood Museum, Matthew Boulton (1728–1809), Wedgwood Museum, retrieved 30 June 2009

- ^ a b The Boulton legacy, Birmingham City Council, retrieved 22 June 2009

- ^ Smiles 1865, pp. 480–81.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 178.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 292.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 291.

- ^ a b Smiles 1865, p. 179.

- ^ Andrew 2009, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Andrew 2009, p. 63.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 246.

- ^ a b Smiles 1865, p. 205.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 248.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 251.

- ^ a b Uglow 2002, pp. 252–53.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 255.

- ^ a b c Andrew 2009, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 294.

- ^ Uglow 2002, pp. 283–86.

- ^ Uglow 2002, pp. 292–94.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 318.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 325.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 327.

- ^ a b c Uglow 2002, p. 376.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 358.

- ^ Smiles 1865, pp. 358–59.

- ^ Andrew 2009, p. 69.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 257.

- ^ Mantoux, Paul (2006) [1928], The Industrial Revolution in the Eighteenth Century (reprint ed.), Taylor & Francis, p. 337, ISBN 978-0-415-37839-0

- ^ Mokyr, Joel (1999), The British Industrial Revolution, Westview Press, p. 185, ISBN 978-0-8133-3389-2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rodgers, Kerry (May 2009), "Boulton father of mechanized press", World Coin News, pp. 1, 56–58

- ^ a b c Lobel 1999, p. 575.

- ^ Tungate 2009, p. 80.

- ^ Mayhew, Nicholas (1999), Sterling: The Rise and Fall of a Currency, The Penguin Group, pp. 104–05, ISBN 978-0-7139-9258-8

- ^ a b c Smiles 1865, p. 399.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 392.

- ^ Delieb 1971, p. 112.

- ^ Symons 2009, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d Symons 2009, p. 94.

- ^ a b "By the King: A proclamation", The London Gazette, 29 July 1797, retrieved 16 June 2009

- ^ Mason 2009, p. 215.

- ^ Lobel 1999, p. 583.

- ^ Clay 2009, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Clay 2009, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Lobel 1999, p. 597.

- ^ Clay 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Clay 2009, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c d Uglow 2009, p. 7.

- ^ a b Uglow 2002, p. 15.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 58.

- ^ a b Uglow 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Uglow 2009, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Uglow 2009, p. 8.

- ^ a b Uglow 2009, p. 9.

- ^ Delieb 1971, p. 27.

- ^ Uglow 2002, pp. 194–96.

- ^ Uglow 2002, pp. 291–92.

- ^ a b c d e Mason 2009, p. 191.

- ^ a b Mason 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Mason 2009, p. 195.

- ^ Delieb 1971, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Mason 2009, p. 197.

- ^ Mason 2009, p. 198.

- ^ Mason 2009, p. 201.

- ^ Mason 2009, p. 202.

- ^ Delieb 1971, pp. 19–23.

- ^ Delieb 1971, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Uglow 2002, p. 495.

- ^ Uglow 2002, p. 475.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 474.

- ^ a b c Walden, Timothy (2002), The Spanish Treasure Fleets, Pineapple Press, p. 195, ISBN 978-1-56164-261-8, retrieved 23 June 2009

- ^ Clay 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Symons 2009, p. 95.

- ^ a b Symons 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Smiles 1865, p. 476.

- ^ a b Noszlopy, George; Beach, Jeremy (1998), Public Sculpture of Birmingham, Liverpool University Press, pp. 67–68, ISBN 978-0-85323-682-5, retrieved 23 June 2009

- ^ Soho House, Birmingham City Council, retrieved 22 June 2009

- ^ Sarehole Mill, Birmingham City Council, retrieved 22 June 2009

- ^ Birmingham Civic Society: Blue Plaques, Birmingham Civic Society, retrieved 11 January 2015

- ^ Boulton, Watt, and Murdoch, Birmingham City Council, retrieved 11 December 2011

- ^

Our History, Matthew Boulton College, archived from the original on 11 March 2007, retrieved 22 June 2009

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Matthew Boulton Bicentenary Celebrations 2009, Birmingham City Council, retrieved 22 June 2009

- ^ Steam giants on new £50 banknote, BBC News, 30 May 2009, retrieved 22 June 2009

- ^ Stewart, Heather (30 September 2011). "Bank of England to launch new £50 note". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ Pioneers of the Industrial Revolution, Royal Mail, retrieved 22 June 2009

References

- Jim, Andrew (2009), "The Soho Steam Engine Business", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 63–70, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Sally, Baggott (2009), "'I am very desirous of being a great silversmith': Matthew Boulton and the Birmingham Assay Office", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 47–54, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Clay, Richard (2009), Matthew Boulton and the Art of Making Money, Brewin Books, ISBN 978-1-85858-450-8

- Delieb, Eric (1971), Matthew Boulton: Master Silversmith, November Books

- Nicholas, Goodison (2009), "Ormolu Ornaments", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 55–62, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Lobel, Richard (1999), Coincraft's 2000 Standard Catalogue of English and UK Coins, 1066 to Date, Standard Catalogue Publishers, ISBN 978-0-9526228-8-8

- Val, Loggie (2009), "Picturing Soho: Images of Matthew Boulton's Manufactory", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 7–13, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Mason, Shena (2009), "'The Hôtel d'amitié sur Handsworth Heath': Soho House and the Boultons", Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 14–21 (other text not part of a contribution also credited here), ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- McLean, Rita (2009), "Introduction: Matthew Boulton, 1728—1809", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 1–6, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Kenneth, Quickenden (2009), "Matthew Boulton and the Lunar Society", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 41–46, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Smiles, Samuel (1865), Lives of Boulton and Watt, London: John Murray

- David, Symons (2009), "'Bringing to Perfection the Art of Coining': What did they make at the Soho Mint?", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 89–98, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Sue, Tungate (2009), "Matthew Boulton's Mints: Copper to Customer", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 80–88, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

- Uglow, Jenny (2002), The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World, London: Faber & Faber, ISBN 978-0-374-19440-6

- Jenny, Uglow (2009), "Matthew Boulton and the Lunar Society", in Mason, Shena (ed.), Matthew Boulton: Selling What All the World Desires, New Haven, Ct.: Yale University Press, pp. 7–13, ISBN 978-0-300-14358-4

Further reading

- Doty, Richard (1998), The Soho Mint and the Industrialization of Money, London: Spink & Son Ltd, ISBN 978-1-902040-03-5

- Goodison, Nicholas (1999), Matthew Boulton: Ormolu, London: Christie's Books, ISBN 978-0-903432-70-2

- Jones, Peter M. (2009), Industrial Enlightenment: Science, Technology and Culture in Birmingham and the West Midlands 1760–1820, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-7770-8

- Roll, Erich; Smith, J. G. (1930), An Early Experiment in Industrial Organisation: Being a History of the Firm of Boulton & Watt, 1775–1805, London: Longmans and Green

- Schofield, Robert E. (1963), The Lunar Society of Birmingham: A Social History of Provincial Science and Industry in Eighteenth-Century England, Oxford: Clarendon Press

External links

- Matthew Boulton Bicentenary Celebrations 2009 on Birmingham Assay Office's website

- Archives at Birmingham Central Library

- Revolutionary Players website

- Cornwall Record Office Boulton & Watt letters

- Soho Mint website, celebrating Matthew Boulton, his mint and its products

- Soho House Museum, Matthew Boulton's home from 1766 till his death in 1809, became a Museum in 1995

- 1728 births

- 1809 deaths

- 18th-century British engineers

- 18th-century English people

- English engineers

- English business theorists

- People of the Industrial Revolution

- High Sheriffs of Staffordshire

- People from Birmingham, West Midlands

- Members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham

- English inventors

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- English silversmiths