Menelik II

| Menelik II | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |

| |

| Emperor of Ethiopia | |

| Reign | 10 March 1889 – 12 December 1913 |

| Coronation | 3 November 1889 |

| Predecessor | Yohannes IV |

| Successor | Iyasu V (designated but uncrowned Emperor of Ethiopia) |

| Born | 17 August 1844 Angolalla, Shewa |

| Died | 12 December 1913 (aged 69) |

| Burial | Ba'eta Le Mariam Monastery prev. Se'el Bet Kidane Meheret Church |

| Spouse | Taytu Betul |

| Issue | Zewditu I Shoa ragad Wossen Seged |

| House | House of Solomon |

| Father | Haile Melekot, King of Shewa |

| Mother | Ijigayehu Adeyamo |

| Religion | Ethiopian Orthodox |

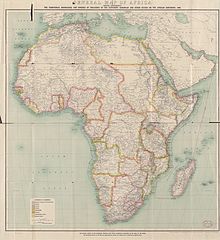

Template:Contains Ethiopic text Emperor Menelik II GCB, GCMG (Template:Lang-gez, dagmäwi minilik [nb 1]), baptized as Sahle Maryam (17 August 1844 – 12 December 1913), was Negus[nb 2] of Shewa (1866–89), then Emperor of Ethiopia[nb 3] from 1889 to his death. At the height of his internal power and external prestige, the process of territorial expansion and creation of the modern empire-state had been completed by 1898, thus restoring the ancient Ethiopian Kingdom to its glory of the Axumite Empire which was one of the four most powerful kingdoms of the ancient world.[1] Ethiopia was transformed under Emperor Menelik: the major signposts of modernization were put in place.[2] Externally, his victory over the Italian invaders had earned him great fame: following the Battle of Adwa, recognition of Ethiopia's independence by external powers was expressed in terms of diplomatic representation at the court of Menelik and delineation of Ethiopia's boundaries with the adjacent colonies.[1] Menelik expanded his kingdom to the south and east, expanding into Kaffa, Sidama, Wolayta and other kingdoms.[3][4] He is widely called Emiye[5] Menelik in Ethiopia for his forgiving nature and his selfless deeds to the poor.

Early life

Abeto Menelik (Sahle Maryam) was born in Angolalla, near Debre Birhan, Shewa. He was the son of Negus Haile Melekot of Shewa and Woizero[nb 4] Ijigayehu. Woizero Ijigayehu was a lady in the household of Haile Melekot's grandmother, the formidable Woizero Zenebework, widow of Merid Azmatch Wossen Seged, and mother of King Sahle Selassie of Showa. Most sources indicate that while no marriage took place between Haile Melekot and Woizero Ijigayehu, Sahle Selassie ordered his grandson legitimized. Menelik II had been born at Angolala in an Oromo area and had lived his first twelve years with Shewan Oromos with whom he thus had much in common.[6]

Prior to his death in 1855, Negus Haile Melekot named Menelik as successor to the throne of Shewa. Shortly after Haile Melekot died, Menelik was taken prisoner by Emperor Tewodros II. Following Emperor Tewodros II's conquest of Shewa, he had young Sahle Maryam transferred to his mountain stronghold of Magdala. Still, Tewodros treated the young prince well. He even offered him the hand of his daughter Altash Tewodros in marriage, which Menelik accepted.

Upon Menelik's imprisonment, his uncle, Haile Mikael, was appointed as Shum[nb 5] of Shewa by Emperor Tewodros II with the title of Meridazmach[nb 6]. However, Meridazmach Haile Mikael rebelled against Tewodros, resulting in his being replaced by the non-royal Ato[nb 7] Bezabeh as Shum. However, Ato Bezabeh in turn then rebelled against the Emperor and proclaimed himself Negus of Shewa. Although the Shewan royals imprisoned at Magdala had been largely complacent as long as a member of their family ruled over Shewa, this usurpation by a commoner was not palatable to them. They plotted the escape of Menelik from Magdala; with the help of Mohammed Ali and Queen Worqitu of Wollo, he escaped from Magdala the night of 1 July 1865, abandoning his wife, and returned to Shewa. Enraged, Emperor Tewodros slaughtered 29 Oromo hostages then had 12 Amhara notables beaten to death with bamboo rods.[7]

King of Shewa

Bezabeh's attempt to raise an army against Menelik failed miserably; thousands of Shewans rallied to the flag of the son of Negus Haile Melekot and even Bezabeh's own soldiers deserted him for the returning prince. Abeto Menelik entered Ankober and proclaimed himself Negus. While Negus Menelik reclaimed his ancestral Shewan crown, he also laid claim to the Imperial throne, as a direct descendant male line of Emperor Lebna Dengel. However, he made no overt attempt to assert this claim during this time; Marcus interprets his lack of decisive action not only to Menelik's lack of confidence and experience, but that "he was emotionally incapable of helping to destroy the man who had treated him as a son."[8] Not wishing to take part in the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia, he allowed his rival Kassai to benefit with gifts of modern weapons and supplies from the British. When Tewodros committed suicide, Menelik II arranged for an official rejoicing and celebration of his death even though he was personally saddened by the loss. When the British asked him why he did this, he replied "to satisfy the passions of the people ... as for me, I should have gone into a forest to weep over ... [his] untimely death ... I have now lost the one who educated me, and toward whom I had always cherished filial and sincere affection."[8] Afterwards other challenges—a revolt amongst the Wollo to the north, the intrigues of his next wife Baffana to replace him with her choice of ruler, military failures against the Arsi Oromo to the south east—kept Menelik from directly confronting Kassai until after his rival had brought an Abuna from Egypt who crowned him Emperor Yohannes IV.

Menelik II was cunning and strategic in building his power base. He organized extravagant three-day feasts for locals to win their favor, liberally built friendships with Muslims (such as Mahammad Ali of Wollo), and struck alliances with the French and Italians who could provide firearms and political leverage against the Emperor. In 1876, an Italian expedition set out to Ethiopia led by Marchese Orazio Antinori who described Menelik II as "he was very friendly, and a fanatic for weapons, about whose mechanism he appears to be most intelligent". Another Italian writes of Menelik II, "[he] had the curiosity of a boy; the least thing made an impression upon him ... He showed ... great intelligence and great mechanical ability". Menelik II spoke with great economy and rapidity. He never became upset, Chiarini adds, "listening calmly, judiciously [and] with good sense ... He is fatalistic and a good soldier, he loves weapons above all else". The visitors also confirmed that he was popular with his subjects, and made himself available to them.[8] Menelik II had great political and military acumen, and made key engagements that would later prove essential as he expanded his Empire.

Submission to Emperor Yohannes

Eventually, Menelik acquiesced to the superior position of Yohannes and, on 20 March 1878, Menelik "approached Yohannes on foot. He was carrying a rock on his neck and his face was down in the traditional form of submission.[9] However, very aware of how precarious his own position was, Yohannes recognized Menelik as Negus of Shewa and gave him numerous presents which included four cannons, several hundred modern Remington rifles, and ammunition for both.[10] Menelik's submission to Yohannes brought twin policies into play: to gain the imperial throne, Menelik had to increase his revenue for the purchase of expensive and modern weapons, and he also had to maintain peace with the emperor and accede to his demands.[8]

Succession

On 10 March 1889, Emperor Yohannes was killed in a war with Mahdist Sudan during the Battle of Gallabat (Matemma). With his dying breaths, Yohannes declared his natural son, Dejazmach Mengesha Yohannes, as his heir. On 25 March, upon hearing of the death of Yohannes, Negus Menelik immediately proclaimed himself as Emperor.[11]

The succession now lay between Mengesha Yohannes of Tigray and Menelik of Shewa. Menelik argued that while the family of Yohannes IV claimed descent from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba through females of the dynasty, his own claim was based on uninterrupted direct male lineage which made the claims of the House of Shewa equal to those of the elder Gondar line of the dynasty. In the end, Menelik was able to obtain the allegiance of a large majority of the Ethiopian nobility. On 3 November 1889, Menelik was consecrated and crowned as Emperor before a glittering crowd of dignitaries and clergy. He was crowned by Abuna Mattewos, Bishop of Shewa, at the Church of Mary on Mount Entoto.[12]

The newly consecrated and crowned Emperor Menelik II quickly toured the north in force. He received the submission of the local officials in Lasta, Yejju, Gojjam, Welo, and Begemder.[11]

Menelik, and later his daughter Zauditu, would be the last Ethiopian monarchs who could claim uninterrupted direct male descent from King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (both Lij Iyasu and Emperor Haile Selassie were in the female line, Iyasu through his mother Shewarega Menelik, and Haile Selassie through his paternal grandmother, Tenagnework Sahle Selassie).[unreliable source?]

Reign as emperor

Centralisation

Menelik II is the actual founder of modern Ethiopia.[13][14] He thought only Russia could be the main ally of his policy of centralisation of territories under Shewan central government by reason of necessity to counteract the British colonial expansion, starting with the war against the British (1868 Expedition to Abyssinia, theft of Kebra Nagast and death of Tewodros II).[15][16]

During the visit of a Russian diplomatic and military mission in 1893, Menelik II concluded a strong alliance with that country. As a result of that alliance, from 1893 to 1913, Russia sponsored the visits of thousands of advisers and volunteers to Ethiopia.[17] Two friendships that evolved from these visits were friendships between Menelik II and Alexander Bulatovich and also between Menelek II and Nikolay Gumilyov the great poet.[15][18][19]

Menelik had in 1898 crushed a rebellion by Ras Mengesha Yohannes (who died in 1906). He directed his efforts thenceforth to the consolidation of his authority, and in a certain degree, to the opening up of his country to western civilization. Menelik’s clemency to Ras Mangasha, whom he compelled to submit and then made hereditary Prince of his native Tigray, was ill repaid by a long series of revolts by that prince. Menelek focused much of his energy on development and modernization of his country after this threat to his throne was firmly ended.

Under his reign, beginning in the 1880s, Menelik set off from the central province of Shoa, to reunify 'the lands and people of the South, East and West into an empire'.[3] During his battles, he made tactical alliance with different groups and appointed Habte Giyorgis Dinagde as Minister of Defense, who was of mixed Gurage-Oromo ancestry. The people incorporated by Menelik through conquest were the unarmed southerners. Oromo, Sidama, Gurage, Wolayta and other groups.[4] He reunited the lands in the south and east. Menelik II had Oromo ancestry himself on his mother's side, and also his late father King Haile Melekot's alliance with the Wollo Oromo helped him militarily.[20][21] He achieved most of his conquests with the help of Ras Gobena's Shewan Oromos, who helped Menelik previously during his clashes with Gojjam.[22]

Menelik brought together many of the northern territories through political consensus with the exception of Gojam which made tribute to Shewan Kingdom following it's defeat at the Battle of Embabo.[23] Most of the western and central territories like Jima, Welega and Chebo were administered by chiefs who allied their clan's army with the central government peacefully. Native armed soldiers of Ras Gobana Dacche, Ras Mikael Ali, Sultan Aba Jifar, Kumsa Mereda, Habtegyorgis Dinegde, Balcha Aba Nefso and Jote Tullu were allied to Menelik's Shewan army which campaigned to the south to incorporate more territories.[24][25][26][27][28][29]

During the conquest of the southern territories, Menelik's Army carried out atrocities against civilians and combatants including torture, mass killings and large scale slavery.[30][31] Large scale atrocities were also committed against the Dizi people and the people of the Kaficho kingdom.[32][33] Some estimates for the number of Southern people(Oromos, Dizi people, Kaffa, Shanqella) killed as a result of the conquest from war, famine and atrocities go into the millions.[30][34][35][36] Aleksandr Bulatovich states that in territories incorporated peacefully like Jima, Leka and Wolega the former order has been preserved and no interfere in their self-government, and in areas incorporated after war the assigned rulers do not violate the people and their religious beliefs and they also treat them lawfully and justly.[37][38][39] He also states that as a result of the famine, which is caused by cattle disease, and the conquest many have died, even half the population in one area he observed and in that particular area he also found a farmstead where half of the population dead due to fever in one year alone.[39][40][41][42]

Before centralization is complete by the end of 19th century, wars have been devastating in the region for many centuries with the last most devastating war fought in 16th century. Warfare system between these two major wars has not much changed and in 16th century the Portuguese Bermudes documented depopulation and that an army led by several successive Aba Gedas carried out atrocities against civilians and combatants including torture, mass killings and large scale slavery during their conquest of territories located north of Genale river (Bali, Amhara, Gafat, Damot, Adal).[43][44] According to Donald, the reasons for warfare in the region is to acquire cattle, slaves, to gain territories or control over trade routes and to carry out ritual requirements or secure trophies to prove masculinity.[45][46][47][48][49] Wars were fought between people who may be under the same linguistic group, religion, culture or between unrelated tribes and the centralization greatly reduced these continuous wars; thereafter, minimizing the loss of lives, raids, destruction and slavery that usually occur during battles of that era.[49][50][51][52][53]

The Great Famine of 1888 to 1892

During Menelik’s reign, the great famine of 1888 to 1892, which was the worst famine in the regions history, had killed a third of the total population then put at 12 million.[54] The famine is caused by a cattle disease which wiped out most of the national livestock, killing over 90% of the cattle.[55] The infection was said to have been introduced by the Italians who had already invoked ‘famine abandoned lands’ to occupy Eritrea to the north and were now seeking protectorate over the rest of Ethiopia.[56] The Italians introduced Rinderpest, an infectious viral disease, to the native cattle population with no prior exposure and were unable to fight off the disease.[55]

Wuchale Treaty

In April 1889, while claiming the throne against Ras Mengesha Yohannes, the "natural son" of Atse Yohannes(Yohanis), Menelik reached at Wuchale (Uccialli in Italian) in Wollo province a treaty with Italy. According to Rick Duncan, on the signing of the treaty, Menelik said "The territories north of the Merab Milesh(Eritrea) do not belong to nor are under my rule. I am the Emperor of Abyssinnia. The lands referred to as Eritrea is not peopled by Abyssinians, they are Adals, Bejaa, and Tigres. Abysinnia will defend his territories but will not fight for foreign lands of which Eritrea is to my knowledge."[57] Menelik signed the Treaty of Wuchale with the Italians on May 2, 1889. Per the Treaty, Ethiopia(Abyssinia) and Italy agreed to define the boundary between Eritrea and Ethiopia. For example, both Ethiopia and Italy agreed that Arafali, Halai, Saganeiti and Asmara are "villages in the Italian border." (See Article III(b) of the treaty). Also, the Italians agreed to not harass Ethiopian traders and, furthermore, Italy agreed to allow safe passage for Ethiopian goods, particularly military weapons.[58] The treaty also guaranteed that the Ethiopian government will have ownership of the Monastery of Debre Bizen but not use it for military purposes.(see Article IV of the Treaty).

However, there were two versions of the treaty to be signed, one in Italian and another in Amharic. Unbeknownst to Menelik the Italian version was altered by the Italian translators to give Italy more power than the two had agreed to. The Italians believed they had "tricked" Menelik into giving allegiance to Italy. To their surprise, upon learning about the alteration, Emperor Menelik II rejected the treaty. The Italians attempted to bribe him with two millions of ammunition but he refused. Then the Italians approached Ras Mengesha of Tigray in an attempt to create civil war, however, Ras Mengesha understanding what was at stake, Ethiopia's independence, he refused to be a puppet for the Italians. Then, the Italians prepared to attack Ethiopia with an army led by Baratieri. Subsequently, the Italians declared war and invaded Ethiopia.

Battle of Adwa

Menelik disagreed with Article 17 of the treaty and this led to the Battle of Adwa. Before Italy could launch the invasion, Eritreans rebelled in an attempt to push Italy out of Eritrea and stop It from invading Ethiopia.[59] The rebellion was not successful. However, some of the Eritreans managed to make their way to the Ethiopian camp and jointly fought Italy at the battle of Adwa. On March 1, 1896 the two armies met at Adwa. The Ethiopians came out victorious.

With the victory at the Battle of Adwa in hand and the Italian colonial army destroyed, Eritrea was Emperor Menelik’s for the taking but no order to occupy was given. It seems that Emperor Menelik II was wiser than the Europeans had given him credit for. Realizing that the Italians would bring all their force to bear on his country if he attacked,[60] he instead sought to restore the peace that had been broken by the Italians and their treaty manipulation seven years before. In signing the treaty, Menelik II again proved his adeptness at politics as he promised each nation something for what they gave and made sure each would benefit his country and not another nation. Subsequently, The Treaty of Addis Ababa was reached between the two nations. Italy was forced to recognize the absolute independence of Ethiopia. (See Article III of the Treaty of Addis Ababa).

Abolition of Slave Trading

By the mid-1890s, Menelik was actively suppressing slave trade, destroying notorious slave market towns and punishing slavers with amputation.[61] Both Tewodros II and Yohannes IV also outlawed slavery but since all tribes were not against slavery and the fact that the country was surrounded on all sides by slave raiders and traders, it was not possible to entirely suppress this practice even by the 20th century.[62] Chris Prouty states that Menelik prohibited Slavery, while it was beyond his capacity to change the mind of his people regarding to this age-old practice that was widely prevalent throughout the country.[63]

Ethnic Make up of Menelik's Government

Various ethnic-groups played great role during Menelik's reign and after that, with Amharas and Oromos holding key positions in the central government.[49][64] Menelik, since he became King of Shewa, gave the top leadership of the military to Ras Gobana Dacche, Ras Makonnen and finally to Fit. HabteGyorgis whom all of them are Oromos.[65] Right after Menelik's death the most dominant person in the empire was Habtegyorgis whom some call him as the "King maker". Negus Mikael before the Battle of Segale is believed to say: "If Habte-Girogis is with us and Teferi is very young ("a child of yesterday"), with whom are we going to fight? Who can defeat us?".[27][66] Mikael's remark and his imprisonment in Habtegyorgis's native land, Chebo, after his defeat at the battle shows that who was effectively running the empire after Menelik's death.[67] With Habtegyorgis, the war minister & primeminister, domination Shewans did overhtrow Mikael's son Lij Iyasu and replaced him With Zewditu Menelik as Queen while assigning the young Teferi Mekonen as heir and regent, also with Oromo decent who later became emperor Haile Selassie.[28][68][69][70] Even decades after Menelik’s death, Oromos continued to hold key positions in the empire and by the time Italians invaded Ethiopia for the second time they dropped leaflets stating “Amhara tyranny” all over the country, and in response to this propaganda Richard Greenfield in his book states that: “Italians appear not to have understood that the leading families are Oromo”.[71]

At the battle of Adowa the Ethiopian fighters from all parts of the country rallied to the cause. They camped in strategic positions in the battlefield that allowed them to come to the aid of one another during combat operations. Armies who participated in the battle includes Negus Tekle Haimanot’s Gojam Amhara infantry and cavalary; Ras Mengesha Yohanis and Ras Aluala’s Tigrayan army; Ras Mekonen’s Harar army that included Amhara, Oromo and Gurage soldiers; Ras Mikael’s mainly muslim Wallo cavalary; Fitawrari Tekle’s Wallaga Cavalary and infantry; Wag-shum Gwangul’s Agaw and Amhara from Wag and Lasta; and Ras Wolle Bitul’s Gondar army that also included Muslim-Christian cavalary from Yejju and Borana Wallo, Ras Wolle is member of the Warasek family from Yejju who used to rule Gondar, the old capital of the empire, before the rise of Tewodros. The mehal safari or the central fighting unit includes mostly Shewan Amhara, Mecha-Tulama Oromo cavalary, Gurage as well as Taytus Bitul’s Yejju armies. The Fitawrari’s army, normally the leader of the advanced guard, was commanded by Gebeyehu Gorra who was part of the Mehal safari which had always to accompany the emperor. The Ethiopian army at Adwa was, therefore, a mosaic of scores of nationalities that marched north for a common cause.[72][73][74]

Developments during Menelik's reign

Menelik II was fascinated by modernity, and like Tewodros II before him, had a keen ambition to introduce Western technological and administrative advances into Ethiopia. The Russian support for Ethiopia led to the advent of a Russian Red Cross mission. The Russian mission was a military mission conceived as medical support for the Ethiopian troops. It arrived in Addis Ababa some three months after Menilek's Adwa victory,[75] and then the first hospital was created in Ethiopia. Following the rush by the major powers to establish diplomatic relations following the Ethiopian victory at Adwa, more and more westerners began to travel to Ethiopia looking for trade, farming, hunting and mineral exploration concessions. Menelik II founded the first modern bank in Ethiopia, the Bank of Abyssinia, introduced the first modern postal system, signed the agreement and initiated work that established the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway with the French, introduced electricity to Addis Ababa, as well as the telephone, telegraph, the motor car and modern plumbing. He attempted unsuccessfully to introduce coinage to replace the Maria Theresa thaler.

Menelik had granted in 1894 a concession for the building of a railway to his capital from the French port of Djibouti but, alarmed by a claim made by France in 1902 to the control of the line in Ethiopian territory, he stopped for four years the extension of the railway beyond Dire Dawa. When in 1906 France, the United Kingdom and Italy came to an agreement on the subject, granting control to a joint venture corporation, Menelek officially reiterated his full sovereign rights over the whole of his empire.

According to one persistent tale, Menelik heard about the modern method of executing criminals using electric chairs during the 1890s, and ordered 3 for his kingdom. When the chairs arrived, Menelik learnt they would not work, as Ethiopia did not yet have an electric power industry. Rather than waste his investment, Menelik used one of the chairs as his throne, sending another to his "second" (Lique Mekwas) Abate Ba-Yalew.[76] Recent research, however, has cast significant doubt on this story, and suggested it was invented by a Canadian journalist during the 1930s.[77]

During a particularly devastating famine caused by Rinderpest early in his reign, Menelik personally went out with a hand-held hoe to furrow the fields to show that there was no shame in plowing fields by hand without oxen, something Ethiopian highlanders had been too proud to consider previously. He also forgave taxes during this particularly severe famine.

Later in his reign, Menelik established the first Cabinet of Ministers to help in the administration of the Empire, appointing trusted and widely respected nobles and retainers to the first Ministries. These ministers would remain in place long after his death, serving in their posts through the brief reign of Lij Iyasu and into the reign of Empress Zauditu. They played a key role in deposing Lij Iyasu.

Private life and death

In 1864, Menelik married Altash Tewodros, whom he divorced in 1865; the marriage produced no children. In 1865, he married Befana Gatchew, whom he divorced in 1882; the marriage produced no children. Finally, in 1883, he married Taytu Betul, who remained his wife until his death. From 1906, for all intents and purposes, Taytu Betul ruled in Menelik's stead during his infirmity. Menelik II and Taytu Betul personally owned 70,000 slaves.[78] Abba Jifar II also is said to have more than 10,000 slaves and allowed his armies to enslave the captives during a battle with all his neighboring clans.[79] This practice was common between various tribes and clans of Ethiopia for thousands of years.[47][51][80]

Woizero Altash Tewodros was a daughter of Emperor Tewodros II and the first wife of Menelik II. She and Menelik were married during the time that Menelik was held captive by Tewodros. The marriage ended when Menelik escaped captivity, abandoning her. She was subsequently remarried to Dejazmatch Bariaw Paulos of Adwa.

Woizero Bafena Wolde Michael was married to Menelik for seventeen years from 1865 to 1882. Her brother was Dejazmatch Tewende Belay Wolde Michael. Woizero Bafena was implicated in a plot to overthrow Menelik when he was King of Shewa. She was widely suspected of being secretly in touch with Emperor Yohannes IV in her ambition to replace her husband on the Shewan throne with one of her sons from a previous marriage. With the failure of her plot, Woizero Bafena was separated from Menelik, but Menelik apparently was still deeply attached to her. An attempt at reconciliation failed, but when his relatives and courtiers suggested new young wives to the King, he would sadly say "You ask me to look at these women with the same eyes that once gazed upon Bafena?", paying tribute both to his ex-wife's great beauty and his own continuing attachment to her.

Empress Taytu Betul was a noblewoman of Imperial blood and a member of one of the leading families of the regions of Semien, Yejju in modern Wollo, and Begemder. Her paternal uncle, Dejazmatch Wube Haile Maryam of Semien, had been the ruler of Tigray and much of northern Ethiopia. She had been married four times previously and exercised considerable influence. Taytu and Menelik were married in a full communion church service and thus fully canonical and insoluble, which Menelik had not had with either of his previous wives. Menelik and Taytu would have no children. Empress Taytu would become Empress consort upon her husband's succession, and would become the most powerful consort of an Ethiopian monarch since Empress Mentewab. She and her uncle Ras wube were two of the most powerful people among descendants of the great Ras Gugsa Mursa. Emperor Yohanes was able to broaden his power base in northern Ethiopia through Taytu's family connections in Begemider, Semien and Yejju; she also served him as his first minister and later as an adviser to Menelik, who also went to the battle of Adwa with her own 5,000 troops.[81][82]

Previous to his marriage to Taytu Betul, Menelik fathered several "natural" children. Three natural children that Menelik recognized were Woizero Shoaregga Menelik, born 1867,[nb 8] Woizero (later Empress) Zauditu Menelik, born 1876,[nb 9] and Abeto Asfa Wossen Menelik, born 1873.

In 1886, Menelik married ten-year-old Zauditu to Ras Araya Selassie Yohannes, the fifteen-year-old son of Emperor Yohannes IV. In May 1888, Ras Araya Selassie died. Woizero Shoaregga was first married to Dejazmatch Wodajo Gobena, the son of Ras Gobena Dachi. They had a son, Abeto Wossen Seged Wodajo, but this grandson of Menelik II was eliminated from the succession due to dwarfism. In 1892, twenty-five-year-old Woizero Shoaregga was married for a second time to forty-two-year-old Ras Mikael of Wollo. They had two children, a daughter Woizero Zenebework, and Menelik's eventual successor, Lij[nb 10] Iyasu. Woizero Zenebework Mikael eventually married at age twelve, the much older Ras Bezabih Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, and died in childbirth a year later. Abeto Asfa Wossen Menelik died when he was about fifteen years of age. Only Shoagarad has present day descendants.

Rumoured natural children of the Emperor include Ras Birru Wolde Gabriel and Dejazmach Kebede Tessema.[citation needed] The latter, in turn, was possibly the natural grandfather of Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam,[citation needed] the communist leader of the Derg, who eventually deposed the monarchy and assumed power in Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991.

As wife of Menelik, Taytu politically married her Yejju and Semien relatives to key Shewan aristocrates like Ras Woldegyorgis Aboye, who was Governor of Kaffa, Ras Mekonen who was governor of Harar, and Menelik's eldest daughter Zewditu Menlik who became Nigeste Negestat of the empire after the overthrow of Lij Iyasu.[83] Taytu's step daughter, Zewditu, was married to her nephew Ras Gugsa wolle who administered Begemider up to the 1930s.[83]

On 27 October 1909, Menelik II suffered a massive stroke and his "mind and spirit died". After that, Menelik was no longer able to reign, and the office was taken over by Empress Taytu.[84] as de facto ruler, until Ras Bitwaddad Tesemma was publicly appointed regent.[85] However, he died within a year, and a council of regency — from which the empress was excluded — was formed in March 1910.

In the early morning hours of 12 December 1913, Emperor Menelik II died. He was buried quickly without announcement or ceremony[84] at the Se'el Bet Kidane Meheret Church, on the grounds of the Imperial Palace. In 1916 Menelik II was reburied in the specially built church at Ba'eta Le Mariam Monastery of Addis Ababa.

Succession

After the death of Menelik II, the council of regency continued to rule Ethiopia. As described above, Lij Iyasu had been designated successor of Menelik II by Empress Taytu in May 1909. However, Lij Iyasu was never crowned Emperor of Ethiopia, and eventually Empress Zewditu I succeeded Menelik II on the 27 September 1916. She was his oldest daughter.

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Dagmäwi means "the second".

- ^ King.

- ^ Nəgusä Nägäst.

- ^ Roughly equivalent to Lady.

- ^ Roughly equivalent to Governor.

- ^ Roughly equivalent to Supreme General.

- ^ Equivalent to Sir or Mr.

- ^ Also spelled "Shoaregga" and "Shewa Regga".

- ^ Eventually Empress of Ethiopia.

- ^ Roughly equivalent to Child.

- ^ The crypts of Menilek (center), Taytu Betul (left), and Zauditu (right).

- Citations

- ^ a b Zewde, Bahru. A history of Ethiopia: 1855-1991. 2nd ed. Eastern African studies. 2001

- ^ Teshale Tibebu, "Ethiopia: Menelik II: Era of", Encyclopedia of African history”, Kevin Shillington (ed.), 2004.

- ^ a b John Young (1998). "Regionalism and Democracy in Ethiopia". Third World Quarterly. 19 (2): 192. doi:10.1080/01436599814415. JSTOR 3993156.

- ^ a b International Crisis Group, "Ethnic Federalism and its Discontents". Issue 153 of ICG Africa report (4 September 2009) p. 2.

- ^ Emiye in Amharic means "My Mother" affectionately"

- ^ "Ethiopia: A New Political History- Google Books": Richard Greenfield, 1965. p. 97.

- ^ Marcus, Harold G. (1995). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844-1913. Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press. p. 24f. ISBN 1-56902-010-8.

- ^ a b c d Marcus, Harold (1975). The Life and Times of Menelik II: Ethiopia 1844-1913. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 57.

- ^ Marcus, Menelik II, p. 55

- ^ Marcus, Menelik II, p. 56

- ^ a b Mockler, p. 89

- ^ Mockler, p. 90

- ^ By Michael B. Lentakis Ethiopia: A View from Within. Janus Publishing Company Lim (2005) pp. 8 Google Books

- ^ Joel Augustus Rogers The Real Facts about Ethiopia. J.A. Rogers, Pubs (1936) pp. 11 Google Books

- ^ a b "Armies". SamizdatTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ "Who Was Count Abai?". RU: SPBTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Cossacks of the emperor ?enelik II

- ^ "Николай Гумилёв. Умер ли Менелик?" (in Russian). RU: GumilevTemplate:Inconsistent citations

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Диссертация "Российско-эфиопские дипломатические и культурные связи в конце XIX-начале XX веков"

- ^ "Though Menelik's mother was an Oromo, this did not factor into Addis Ababa's early spatial development "

- ^ Abir, Ethiopia, p. 180.

- ^ Edward C. Keefer (1973). "Great Britain and Ethiopia 1897–1910: Competition for Empire". International Journal of African Studies. 6 (3): 470. JSTOR 216612.

- ^ Kevin Shillington Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set (2013) pp. 506 Google Books

- ^ Paul B. Henze Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (2000) pp. 196 Google Books

- ^ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 45 Google Books

- ^ Paul B. Henze Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (2000) pp. 208 Google Books

- ^ a b Gebre-Igziabiher Elyas, Reidulf Knut Molvaer Prowess, Piety and Politics: The Chronicle of Abeto Iyasu and Empress Zewditu of Ethiopia (1909-1930) (1994) pp. 370 Google Books

- ^ a b John Markakis Ethiopia: The Last Two Frontiers (2011) pp. 109 Google Books

- ^ Richard Alan Caulk, Bahru Zewde "Between the Jaws of Hyenas": A Diplomatic History of Ethiopia, 1876-1896. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2002 pp. 415 Google Books

- ^ a b Mohammed Hassen, Conquest, Tyranny, and Ethnocide against the Oromo: A Historical Assessment of Human Rights Conditions in Ethiopia, ca. 1880s–2002 , Northeast African Studies Volume 9, Number 3, 2002 (New Series)

- ^ Mekuria Bulcha, Genocidal violence in the making of nation and state in Ethiopia, African Sociological Review

- ^ Alemayehu Kumsa, Power and Powerlessness in Contemporary Ethiopia, Charles University in Prague

- ^ Haberland, "Amharic Manuscript", pp. 241f

- ^ Alemayehu Kumsa, Power and Powerlessness in Contemporary Ethiopia, Charles University in Prague pp. 1122

- ^ Eshete Gemeda, African Egalitarian Values and Indigenous Genres: A Comparative Approach to the Functional and Contextual Studies of Oromo National Literature in a Contemporary Perspective, pp 186

- ^ A. K. Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898, translated by Richard Seltzer, 2000 pp. 68

- ^ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 69.

- ^ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 68.

- ^ a b Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898" samizdat 1993

- ^ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 11.

- ^ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 12.

- ^ Aleksandr Ksaver'evich Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898- Google Books": , 2000. p. 68.

- ^ Richard Pankhurst The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century - Google Books": , 1997. p. 284.

- ^ J. Bermudez The Portuguese expedition to Abyssinia in 1541-1543 as narrated by Castanhoso - Google Books": , 1543. p. 229.

- ^ Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 43 Google Books

- ^ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 107 Google Books

- ^ a b Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 56 Google Books

- ^ Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- ^ a b c Prof. Feqadu Lamessa History 101: Fiction and Facts on Oromos of Ethiopia. Salem-News.com (2013)

- ^ Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 156 Google Books

- ^ a b Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 136 Google Books

- ^ Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 85 Google Books

- ^ Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 26 Google Books

- ^ Peter Gill Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid OUP Oxford, 2010 Google Books

- ^ a b Paul Dorosh, Shahidur Rashid Food and Agriculture in Ethiopia: Progress and Policy Challenges University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012 pp. 257 Google Books

- ^ Peter Gill Famine and Foreigners: Ethiopia Since Live Aid OUP Oxford, 2010 Google Books

- ^ Man, Know Thyself: Volume 1 Corrective Knowledge of Our Notable Ancestors by Rick Duncan, page 328

- ^ "The Treaty of Wuchale" (PDF).

- ^ Haggai, Erlich (1997). Ras Alula and the scramble for Africa -a political biography: Ethiopia and Eritrea 1875-1897. African World Press.

- ^ Lewis, D.L (1988). The Race to Fashoda: European Colonialism and African Resistance in the Scramble for Africa (1 ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-0113-0.

- ^ Raymond Jonas The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (2011) pp. 81 Google Books

- ^ Jean Allain The Law and Slavery: Prohibiting Human Exploitation (2015) pp. 128 Google Books

- ^ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 16 Google Books

- ^ Ethiopia: A New Political History- Google Books": Richard Greenfield, 1965. p. 97.

- ^ Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, second edition (London: James Currey, 2001), p. 115

- ^ Messay Kebede Survival and modernization--Ethiopia's enigmatic present: a philosophical discourse. Red Sea Press (1999) pp. 38 Google Books

- ^ Gebre-Igziabiher Elyas, Reidulf Knut Molvaer Prowess, Piety and Politics: The Chronicle of Abeto Iyasu and Empress Zewditu of Ethiopia (1909-1930) (1994) pp. 376 Google Books

- ^ Lars Berge, Irma Taddia Themes in Modern African History and Culture (2013) pp. 185 Google Books

- ^ Yohannes K. Mekonnen Ethiopia: The Land, Its People, History and Culture (2013) pp. 272 Google Books

- ^ Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- ^ Richard Greenfield Ethiopia: A New Political History- Google Books": 1965. p. 230.

- ^ Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism - Google Books": 2005. p. 53.

- ^ Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia The Battle of Adwa: Reflections on Ethiopia's Historic Victory Against European Colonialism - Google Books": 2005. p. 77.

- ^ Molla Tikuye, The Rise and Fall of the Yajju Dynasty 1784-1980, p. 201.

- ^ The Russian Red Cross Mission

- ^ Wallechinsky, David, Irving Wallace, and Amy Wallace. "The People's Almanac's 15 Favorite Oddities of All Time." The People's Almanac Presents the Book of Lists. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1977. pp. 463-467.

- ^ Dash, Mike, "The Emperor's electric chair". A Blast From the Past, 16 June 2010.

- ^ Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, editor; Anthony; consultants, Andrew Newman, historical (2008). Encyclopedia of the peoples of Africa and the Middle East. New York: Facts On File. p. 516. ISBN 143812676X.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saïd Amir Arjomand Social Theory and Regional Studies in the Global Age (2014) pp. 242 Google Books

- ^ Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 156 Google Books

- ^ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 25 Google Books

- ^ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 156 & 157 Google Books

- ^ a b Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 219 Google Books

- ^ a b ( Chris Prouty, 1986, Empress Taytu and Menelik II)

- ^ Marcus, Menelik II, p. 241.

References

- Lewis, David Levering (1987). The Race to Fashoda: Pawns of Pawns. New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 1-55584-058-2.

- Henze, Paul B. (2000). "Yohannes IV and Menelik II: The Empire Restored, Expanded, and Defended". Layers of Time, A History of Ethiopia. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-22719-1.

- Mockler, Anthony (2002). Haile Sellassie's War. New York: Olive Branch Press. ISBN 978-1-56656-473-1.

- Chris Prouty. Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia 1883-1910. Trenton: The Red Sea Press, 1986. ISBN 0-932415-11-3

- A. K. Bulatovich Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes: Country in Transition, 1896-1898, translated by Richard Seltzer, 2000

- With the Armies of Menelik II, emperor of Ethiopia at www.samizdat.com A.K. Bulatovich With the Armies of Menelik II translated by Richard Seltzer

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Harold G. Marcus (January 1995). The life and times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844-1913. Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-009-8.

External links

- Imperial Ethiopia Homepages - Emperor Menelik II the Early Years

- Imperial Ethiopia Homepages - Emperor Menelik II the Later Years

- Ethiopian Treasures - Emperor Menelik II

- 'The Emperor's electric chair' - Critical re-examination of a popular legend concerning Menelik II

- - Who is the count ?bay?

- A recorded message from Menelik II to Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom on YouTube (In Amharic, from June 4, 1899; The British Library (search phrase "Menelik II")).

- 1844 births

- 1913 deaths

- 19th-century monarchs in Africa

- People from Amhara Region

- Rulers of Shewa

- Solomonic dynasty

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Ethiopian Oriental Orthodox Christians

- Ethiopian Orthodox Christians

- Non-Chalcedonian Christian monarchs

- Orthodox monarchs

- 19th-century Ethiopian people

- 20th-century Ethiopian people

- People of the First Italo-Ethiopian War