Ona Judge

Oney Judge | |

|---|---|

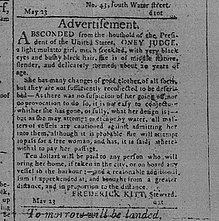

"Advertisement," The Philadelphia Gazette & Universal Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 24, 1796 (2365). | |

| Born | c.1773 |

| Died | February 25, 1848 (aged 75) Greenland, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Spouse | Jack Staines |

| Children | Eliza Staines Nancy Staines Will Staines |

| Parent(s) | Andrew Judge Betty Davis |

Oney "Ona" Judge (c.1773—February 25, 1848), known as Oney Judge Staines after marriage, was an mixed-race slave on George Washington's plantation, Mount Vernon, in Virginia.[1] Beginning in 1789, she worked as a personal slave to First Lady Martha Washington in the presidential households in New York City and Philadelphia. With the aid of Philadelphia's free black community, Judge escaped to freedom in 1796[2] and lived as a fugitive slave in New Hampshire for the rest of her life.

More is known about her than any other of the Mount Vernon slaves, because she was twice interviewed by abolitionist newspapers in the mid-1840s.[3]

Youth

She was born about 1773 at Mount Vernon.[4] Her mother, Betty, was an enslaved seamstress; her father, Andrew Judge, was an English tailor working as an indentured servant at Mount Vernon. Oney had a half-brother Austin (c. 1757 – December 1794),[5] and later a half-sister Delphy (c. 1779 – December 13, 1831).[6]

Betty had been among the 285 African slaves held by Martha Washington's first husband, Daniel Parke Custis (1711–1757). Custis died intestate (without a will), so his widow received a "dower share" – the lifetime use of one third of his Estate, which included at least 85 enslaved Africans.[7] Martha had control over these "dower" slaves, but did not have the legal power to sell or free them. Upon Martha's marriage to George Washington in 1759, the dower slaves came with her to Mount Vernon, including Betty and then-infant Austin.

Under the legal principle of partus sequitur ventrem, incorporated into Virginia colonial law in 1662, the legal status of a child was the same as that of the enslaved mother, no matter who the father was. Because Betty was a dower slave, Austin, Oney and Delphy also were dower slaves, owned by the Custis Estate. Upon the completion of his indenture, Andrew Judge settled in Alexandria, Virginia, some 11 miles away.

At about age 10, Oney was brought to live at the Mansion House at Mount Vernon, likely as a playmate for Martha Washington's granddaughter Nelly Custis. She eventually became the personal attendant or body servant to Martha Washington. In an interview when she was nearly 75, Oney said she had received no education under the Washingtons, nor religious instruction.[8]

Presidential household

Washington took seven enslaved Africans, including Judge, then 16, to New York City in 1789 to work in his presidential household; the others were her half-brother Austin, Giles, Paris, Moll, Christopher Sheels, and William Lee. Following the transfer of the national capital to Philadelphia in 1790, Judge was one of nine slaves Washington took to that city to work in the President's House, together with Austin, Giles, Paris, Moll, Hercules, Richmond, Christopher Sheels, and "Postilion Joe" (Richardson).[9][10]

Gradual Abolition Act

With the 1780 Gradual Abolition Act, Pennsylvania became the first state to establish a process to emancipate its slaves. But no one was freed at first. The process was to play out over decades and not end until the death of the last enslaved person in Pennsylvania.[11]

The law immediately prohibited importation of slaves into the state, and required an annual registration of those already held there. But it also protected the property rights of Pennsylvania slaveholders—if a slaveholder failed to register his slaves, they would be confiscated and freed; but if a slaveholder complied with the state law and registered them every year, they would remain enslaved for life. Every future child of an enslaved mother would be born free, but the child was required to work as an indentured servant to the mother's master until age 28. A slaveholder from another state could reside in Pennsylvania with his personal slaves for up to six months, but if those slaves were held in Pennsylvania beyond that deadline, the law gave them the power to free themselves.[12] Congress, then the only branch of the federal government, was meeting in Philadelphia in 1780 (it met there until 1783). Significantly, Pennsylvania exempted members of Congress from the Gradual Abolition Act.[11]

A 1788 amendment to the state law closed loopholes – such as by prohibiting a Pennsylvania slaveholder from transporting a pregnant woman out of the state (so the child would be born enslaved) and prohibiting a non-resident slaveholder from rotating his slaves in and out of the state to prevent them from establishing the six-month Pennsylvania residency required to qualify for freedom[13] This last point would affect the lives of Oney Judge and the other President's House slaves.

In March 1789, the U.S. Constitution was ratified, creating a federal government with three branches. New York City was the first national capital under the Constitution; it had no laws restricting slaveholding. In 1790 Congress transferred the national capital to Philadelphia for a ten-year period while the permanent national capital was under construction on the banks of the Potomac River. With the move, there was uncertainty about whether Pennsylvania's slavery laws would apply to officers of the federal government. By a strict interpretation, the Gradual Abolition Act exempted only slaveholding members of Congress. But there were slaveholders among the officers of the judicial branch (Supreme Court) and the executive branch, including the President of the United States.[11]

Washington contended (privately) that his presence in Philadelphia was solely a consequence of the city's being the temporary seat of the federal government. He held that he remained a resident of Virginia, and should not be bound by Pennsylvania law regarding slavery. Attorney General Edmund Randolph – also an officer of the executive branch – misunderstood the Pennsylvania law and lost his personal slaves after they established a six-month residency and claimed their freedom. Randolph immediately warned Washington to prevent the President's House slaves from doing the same, advising him to interrupt their residency by sending them out of the state.[14] Such a rotation was a violation of the 1788 amendment, but Washington's actions were not challenged. He continued to rotate the President's House slaves in and out of Pennsylvania throughout his presidency. He also was careful never to spend six continuous months in Pennsylvania himself, which could be interpreted as establishing legal residency.[11]

Washington was on his Southern Tour in May 1791, when the first six-month deadline approached.[15] Giles and Paris had left Pennsylvania with him in April; Austin and Richmond were sent back to Mount Vernon prior to the deadline to prevent them from qualifying for freedom. Martha Washington took Oney Judge and Christopher Sheels to Trenton, New Jersey, for two days to interrupt their Pennsylvania residency.[16] Moll and Hercules were allowed to remain in Pennsylvania for a couple days beyond the deadline, then traveled back to Mount Vernon with the First Lady.[11]

A 1791 proposal in the Pennsylvania legislature to amend the Gradual Abolition Act to extend Congress's exemption to all slaveholding officers of the federal government was abandoned after heated opposition by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.[11]

In 1842 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Prigg v. Pennsylvania that the 1788 amendment to the Gradual Abolition Act – specifically the section that empowered Pennsylvania to free the slaves of non-resident slaveholders – was unconstitutional.[11]

Escape

Judge fled as the Washingtons were preparing to return to Virginia for a short trip between sessions of Congress. Martha Washington had informed her that she was to be given as a wedding present to the First Lady's granddaughter. Judge recalled in an 1845 interview:

"Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn't know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty. I had friends among the colored people of Philadelphia, had my things carried there beforehand, and left Washington's house while they were eating dinner."[17]

Runaway advertisements in Philadelphia newspapers document Judge's escape to freedom from the President's House on May 21, 1796. This one appeared in The Philadelphia Gazette & Universal Daily Advertiser on May 24, 1796:

Advertisement.

Absconded from the household of the President of the United States, ONEY JUDGE, a light mulatto girl, much freckled, with very black eyes and bushy hair. She is of middle stature, slender, and delicately formed, about 20 years of age.

She has many changes of good clothes, of all sorts, but they are not sufficiently recollected to be described—As there was no suspicion of her going off, nor no provocation to do so, it is not easy to conjecture whither she has gone, or fully, what her design is; but as she may attempt to escape by water, all masters of vessels are cautioned against admitting her into them, although it is probable she will attempt to pass for a free woman, and has, it is said, wherewithal to pay her passage.

Ten dollars will be paid to any person who will bring her home, if taken in the city, or on board any vessel in the harbour;—and a reasonable additional sum if apprehended at, and brought from a greater distance, and in proportion to the distance.

FREDERICK KITT, Steward. May 23

New Hampshire

Judge was secretly placed aboard the Nancy, a ship piloted by Captain John Bowles and bound for Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[18] She may have thought she had found safe haven, but that summer she was recognized on the streets of Portsmouth by Elizabeth Langdon, the teenage daughter of Senator John Langdon and a friend of Nelly Custis. Washington knew of Judge's whereabouts by September 1, when he wrote to Oliver Wolcott, Jr., the Secretary of the Treasury, about having her captured and returned by ship.[19]

At Wolcott's request, Joseph Whipple, Portsmouth's collector of customs, interviewed Judge and reported back to him. The plan to capture her was abandoned after Whipple warned that news of an abduction could cause a riot on the docks by supporters of abolition. Whipple refused to place Judge on a ship against her will, but relayed to Wolcott her offer to return voluntarily to the Washingtons if they would guarantee to free her following their deaths.[20]

"... a thirst for compleat freedom ... had been her only motive for absconding." — Joseph Whipple to Oliver Wolcott, October 4, 1796.

An indignant Washington responded himself to Whipple:

"I regret that the attempt you made to restore the Girl (Oney Judge as she called herself while with us, and who, without the least provocation absconded from her Mistress) should have been attended with so little Success. To enter into such a compromise with her, as she suggested to you, is totally inadmissible, for reasons that must strike at first view: for however well disposed I might be to a gradual abolition, or even to an entire emancipation of that description of People (if the latter was in itself practicable at this moment) it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference [of freedom]; and thereby discontent before hand the minds of all her fellow-servants who by their steady attachments are far more deserving than herself of favor."[21]

Washington retired from the presidency in March 1797. His nephew, Burwell Bassett Jr., traveled to New Hampshire on business in September 1798, and tried to convince her to return. By this point she was married to a seaman named Jack Staines (who was away at sea) and was the mother of an infant. Bassett met with her, but she refused to return to Virginia with him. Bassett was Senator Langdon's houseguest that night, and over dinner he revealed his plan to kidnap her. This time Langdon helped Judge Staines, secretly sending word for her to immediately go into hiding. Bassett returned to Virginia without her.[22]

Washington could have used the federal courts to recover Judge Staines — the 1793 Fugitive Slave Act (which he had signed into law) required a legal process to return an escaped slave over state lines. Any court case, however, would have been part of the public record, and attracted unwelcome attention.

Following Judge's 1796 escape, her younger sister, Delphy,[23] became the wedding present to Martha Washington's granddaughter. Eliza Custis Law and her husband manumitted Delphy and her children in 1807, after they were already living with husband William Costin in Washington City.[24]

Family

In New Hampshire, Oney Judge met and married Jack Staines, a free black sailor. Their January 1797 marriage was listed in the town records of Greenland and published in the local newspaper.[25] They had three children:

- Eliza Staines (born 1798, died February 14, 1832, New Hampshire, no known offspring)

- Will Staines (born 1801, death date & location unknown, no known offspring)

- Nancy Staines (born 1802, died February 11, 1833, New Hampshire, no known offspring)

In freedom, Judge Staines learned to read and became a Christian.[8] She and her husband had fewer than 7 years together; he died on October 19, 1803.[26] As a widow, Judge Staines was unable to support her children and moved in with the family of John Jacks, Jr.[22] Her daughters Eliza and Nancy became wards of the town and were hired out as indentured servants; her son Will was apprenticed as a sailor.[22]

Judge Staines' daughters died fifteen years before she did. Her son reportedly never returned to Portsmouth. After the elder Jacks died, Rockingham County donated firewood and other supplies to Judge and the Jacks sisters, by then too old to work.[22]

Interviews on slavery

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Interviews with Judge Staines were published in the May 1845 issue of The Granite Freeman and the January 1847 issue of The Liberator, both abolitionist newspapers. They contained a wealth of details about her life. She described the Washingtons, their attempts to capture her, her opinions on slavery, her pride in having learned to read, and her strong religious faith. When asked whether she was sorry that she left the Washingtons, since she labored so much harder after her escape than before, she said: "No, I am free, and have, I trust been made a child of God by the means."[27]

Never freed

George Washington died on December 14, 1799; he directed in his will that his 124 slaves be freed after his wife's death.[28] Martha instead signed a deed of manumission in December 1800,[29] and the slaves were free on January 1, 1801.[30] The 153 or so dower slaves at Mount Vernon remained enslaved, as neither George nor Martha could legally free them.

Following Martha Washington's death in 1802, the dower slaves reverted to the Custis estate, and were divided among the Custis heirs, her grandchildren.[31]

Oney Judge remained a dower slave all her life, and legally her children also were dower slaves, property of the Custis estate, despite the fact that their father, Jack Staines, was a free man. Article IV, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the property rights of slaveholders; this superseded Staines's parental rights.[32]

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 — passed overwhelmingly by Congress and signed into law by Washington — established the legal mechanism by which a slaveholder could recover his property. The Act made it a federal crime to assist an escaped slave or to interfere with his capture, and allowed slave-catchers into every U.S. state and territory.[33]

Following Washington's death, Oney Judge Staines probably felt secure in New Hampshire, as no one else in his family was likely to mount an effort to take her.[22] But legally, she and her children remained fugitives until their deaths. Her daughters predeceased her by more than a decade, and it is not known what happened to her son.

Oney Judge Staines died in Greenland, New Hampshire, on February 25, 1848.

Legacy and honors

On February 25, 2008, the 160th anniversary of Judge's death, Philadelphia celebrated the first "Oney Judge Day" at the President's House site. The ceremony included speeches by historians and activists, a proclamation by Mayor Michael A. Nutter, and a memorial citation by the City Council.[34]

"Oney Judge Freedom Day," the 214th anniversary of her escape to freedom, was celebrated at the President's House site on May 21, 2010.[35] The President's House Commemoration: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation, at 6th & Market Streets in Philadelphia, opened in December 2010. It includes a video about Oney Judge and information about all nine slaves held at the house.[36] It also honors the contributions of African Americans to Philadelphia and the U.S.

In popular culture

Oney Judge's life story has inspired fiction:

- Taking Liberty (2002), novel by Ann Rinaldi

- The Escape of Oney Judge (2007) by Emily Arnold McCully (children's book).

- My Name Is Oney Judge (2010) by Diane D. Turner (children's book).

and drama:

- Thirst for Freedom (2000 drama) by Emory Wilson, produced that year at Player's Ring Theater, Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

- A House with No Walls (2007 drama) by Thomas Gibbons, performed at InterAct Theater, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and regional theaters throughout the United States.

Other genres:

- Parallel Destinies (2010) by choreographer Germaine Ingram, composer Bobby Zankel, and visual artist John Dowell is a dance/theater piece, a work-in-progress at the Philadelphia Folklore Project.

- Stand-up comedian Jen Kirkman recounts Oney Judge's life in an episode of the Funny or Die produced web video series, Drunk History.[37]

- The freedom Quest of Oney Judge (2015) HERO Live! from Colonial Williamsburg supports American history education for students in grades 4-8. Using 21st century technology and dramatizations with re-enactors to play the roles of historical figures, the HERO Live! programs are correlated to standards, providing a compelling learning experience.[38]

See also

- Alexander Macomb House (New York City) — Second Presidential Mansion.

- Hercules, Washington's cook at the Philadelphia Presidential Mansion, who later escaped to freedom from Mount Vernon

- List of slaves

- Samuel Osgood House (New York City) — First Presidential Mansion.

References

- ^ Dunbar, Erica Armstrong (February 16, 2015). "George Washington, Slave Catcher". New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Runaway advertisement, The Philadelphia Gazette & Universal Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), May 24, 1796.

- ^ Two 1840s interviews with Oney Judge, President's House, US History. In the interviews, her first name is spelled "O-N-A", but all prior references spell it "O-N-E-Y".

- ^ The February 18, 1786 Mount Vernon slave census lists "Oney" as Betty's child and "12 yrs. old". Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington, vol. 4, (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia), p. 278.

- ^ Austin, from Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington.

- ^ In 1800, Delphy married William Costin and moved to Washington, D.C. Costin was named as cousin of Mary Simpson (c. 1752-March 18, 1836), of New York in her will.

- ^ The 85 dower slaves is a minimum number, because the Custis Estate Inventory lists some of the women's names with the notation "& children," but not the number of children. See Edward Lawler, Jr., "President's House Slavery by the Numbers," from ushistory.org

- ^ a b Rev. T.H. Adams, "Washington's Runaway Slave", The Granite Freeman, 22 May 1845, at President's House website, US History.org, accessed 1 April 2012

- ^ The President's House in Philadelphia, US History.org

- ^ Postilion Joe's wife Sarah took the surname Richardson after she was freed by Washington's will. As a "dower slave," Joe could not be freed by Washington.

- ^ a b c d e f g Edward Lawler Jr.,. "Washington, the Enslaved, and the 1780 Law". President's House of Philadelphia. US History.org. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Pennsylvania's Gradual Abolition Act (1780)", President's House of Philadelphia, US History.org

- ^ 1788 amendment, President's House of Philadelphia, US History.org

- ^ "This being the case, the Attorney General conceived, that after six months residence, your slaves would be upon no better footing than his. But he observed, that if, before the expiration of six months, they could, upon any pretense whatever, be carried or sent out of the State, but for a single day, a new era would commence on their return, from whence the six months must be dated for it requires an entire six months for them to claim that right." Tobias Lear to George Washington, 24 April 1791.

- ^ Archibald Henderson, "Washington's Southern Tour, 1791," The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Vol. 26, No. 1 (January, 1925), pp. 59–64.

- ^ Gen. Philemon Dickinson House

- ^ "Washington's Runaway Slave", The Granite Freeman, Concord, New Hampshire (May 22, 1845); carried at President's House in Philadelphia, Independence Hall Association, accessed 11 February 2011

- ^ Gerson, Evelyn. "Ona Judge Staines: Escape from Washington". Retrieved 2012-11-17.

- ^ George Washington to Oliver Wolcott, Sept. 1, 1796

- ^ Joseph Whipple to Oliver Wolcott, October 4, 1796, Library of Congress

- ^ Washington to Whipple, November 28, 1796.

- ^ a b c d e Eva Gerson, "Ona Judge Staines: Escape from Washington", 2000, Black History, SeacoastNH

- ^ Jackson & Twohig, Diaries, vol. 4, p. 278. Note: Delphy is listed as "6 yrs. old" in the February 18, 1786 Mount Vernon slave census.

- ^ Washington, D.C. Land Records, Liber H, #8, p. 382; Liber R, #17, p. 288, as quoted in Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), p. 383, n.13.

- ^ Fritz Hirschfeld, George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal (University of Missouri, 1997), pp. 112-17.

- ^ Evelyn Gerson, A Thirst for Complete Freedom: Why Fugitive Slave Ona Judge Staines Never Returned to Her Master, President George Washington (M.A. thesis, Harvard University, June 2000), p. 130

- ^ "Washington's Runaway Slave", The Granite Freeman, Concord, New Hampshire (May 22, 1845), President's House, Independence Hall Association, US History.org, accessed 11 February 2011

- ^ "Rediscovering George Washington . Last Will and Testament - PBS". 6 February 2005. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ George Washington Pamphlets. 1885-01-01.

- ^ "George Washington and Slavery · George Washington's Mount Vernon". 2015-09-05. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The numbers of Washington slaves and Custis slaves come from the 1799 Mount Vernon slave census., George Washington Papers, University of Virginia

Without documentation, the names of which dower slaves were distributed to which Custis grandchild have to be inferred by comparing names in Mount Vernon records with Custis family records. This has created a frustrating obstacle for genealogists and people trying to research their family history. - ^ The legal status of a child born following an enslaved mother's escape to another (free) state was the same as if that child had been born in the mother's native (slave) state. The U.S. Constitution protected the property rights of the slaveholder, which superseded the rights of the child's father. See U.S. Supreme Court, Jones vs. Van Zandt (1847).

- ^ Finkelman, An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity

- ^ Stephan Salisbury, "City honors Washington's slave - and 'power of archaeology'", The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 26, 2008, at President's House of Philadelphia, US History.org

- ^ "Slave's escape commemorated at President's House", The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 21, 2010

- ^ "The President's House: Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation", City of Philadelphia, accessed 11 February 2011

- ^ "Drunk History vol. 3".

- ^ "Colonial Williamsburg HERO Live! : The Colonial Williamsburg Official History & Citizenship Site". www.history.org. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

Further reading

- Mechal Sobel's The World They Made Together: Black and White Values in Eighteenth Century Virginia, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1987

- Prof. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History Random House, 2007 (p. 128)

External links

- "Two 1840s Articles on Oney Judge", The Granite Freeman (1845) and The Liberator (1847), at President's House website, US History

- (Video) Silent No Longer: The Story of Oney Judge, Philadelphia Inquirer (via YouTube)