Partition (politics)

Appearance

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

In politics, a partition is a change of political borders cutting through at least one territory considered a homeland by some community.[1] That change is done primarily by diplomatic means, and use of military force is negligible.[citation needed]

Common arguments for partitions include:

- historicist — that partition is inevitable, or already in progress[1]

- last resort — that partition should be pursued to avoid the worst outcomes (genocide or large-scale ethnic expulsion), if all other means fail[1]

- cost-benefit — that partition offers a better prospect of conflict reduction than the if existing borders are not changed[1]

- better tomorrow — that partition will reduce current violence and conflict, and that the new more homogenized states will be more stable[1]

- rigorous end — heterogeneity leads to problems, hence homogeneous states should be the goal of any policy[1]

Common arguments against include:

- It disrupts functioning and traditional state entities

- It creates enormous human suffering

- It creates new grievances that could eventually lead to more deadly violence, such as the Korean and Vietnamese wars.

- It prioritizes race and ethnicity to a level acceptable only to an apartheid regime

- The international system is very reluctant to accept the idea of partition in deeply divided societies

Examples

Notable examples are: (See Category:Partition)

- Partition of Africa (Scramble for Africa), between 1881 and 1914.

- Partition, multiple times, of the Roman Empire into the Eastern Roman Empire and the Western Roman Empire, following the Crisis of the Third Century.

- Partition of Prussia by the Second Peace of Thorn in 1466[2] [3] creating Royal Prussia, and Duchy of Prussia in 1525[4]

- Partition of Catalonia by the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659: Northern Catalan territories (Roussillon) was given to France by Spain.

- In the 1757 Second Treaty of Versailles, France agreed upon the partition of Prussia[5]

- Partition of the United States during the American Civil War.

- Partition of Prussia in 1919[6]

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia[7] and Munich Agreement of 1938

- Partition and Elimination[8] of East Prussia[9] among People's Republic of Poland and Soviet Union[10]

- Three Partitions of Luxembourg, the last of which in 1839, that divided Luxembourg between France, Prussia, Belgium, and the independent Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

- Three Partitions of Poland and Poland-Lithuania in the 18th, with the fourth one sometimes referring to events of 19th and 20th centuries

- 1905 Partition of Bengal and 1947 Partition of Bengal

- Partition of Tyrol by the London Pact of 1915

- Partition of the German Empire in 1919 by the Treaty of Versailles

- Partition of the Ottoman Empire

- Partition of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in 1919 by the Treaty of St. Germain

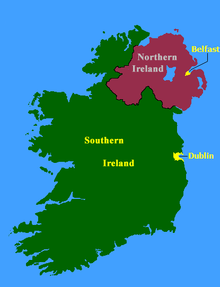

- Partition of Ireland in 1920 into the independent Irish Free State and (British) Northern Ireland

- Treaty of Kars of 1921, which partitioned Ottoman Armenia between the republic of Turkey and the then Soviet Union (Western and Eastern Armenia)

- Partition of Germany and Berlin after World War II, annexation of former eastern territories of Germany

- Partition of Korea in 1945

- 1947 UN Partition Plan for Palestine (region); this partition was abortive, as the proposed Palestinian state was never formed; Israel took most of the territory, with some going to Transjordan and Egypt.

- Partition of India (colonial British India) in 1947 into the independent dominions (later republics) of India and Pakistan (which included modern-day Bangladesh)

- Partition of Korea in 1953

- Partition of Punjab in 1966 into the states of Punjab, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh

- Partition of Pakistan in 1971, when East Pakistan became the independent nation of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War

- Partition of Vietnam in 1954

- The hypothetical partition of the Canadian province of Quebec

- Partition of Yugoslavia in the 1990's

- Possible Partition of Kosovo after disputed independence in 2008.

- Partitions of China (See 瓜分中國)

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Brendan O’Leary, DEBATING PARTITION: JUSTIFICATIONS AND CRITIQUES

- ^ Norman Davies: God's Playground [1]

- ^ Stephen R. Turnbull, Tannenberg 1410: Disaster for the Teutonic Knights [2]

- ^ Elements of General History: Ancient and Modern, by Millot (Claude François Xavier) [3]

- ^ Arthur Hassall, The Balance of Power. 1715–1789 [4]

- ^ Norman Davies: God's Playground [5]

- ^ The Polish Occupation. Czechoslovakia was, of course, mutilated not only by Germany. Poland and Hungary also each asked for their share – Hubert Ripka: Munich, Before and After: A Fully Documented Czechoslovak Account of the ..., 1939 [6]

- ^ Samuel Leonard Sharp: Poland, White Eagle on a Red Field, [7]

- ^ Norman Davies: God's Playground [8]

- ^ Debates of the Senate of the Dominion of Canada [9]