Plant disease resistance

Plant disease resistance protects plants from pathogens in two ways: by pre-formed structures and chemicals, and by infection-induced responses of the immune system. Relative to a susceptible plant, disease resistance is the reduction of pathogen growth on or in the plant, while the term disease tolerance describes plants that exhibit little disease damage despite substantial pathogen levels. Disease outcome is determined by the three-way interaction of the pathogen, the plant and the environmental conditions (an interaction known as the disease triangle).

Defense-activating compounds can move cell-to-cell and systemically through the plant vascular system. However, plants do not have circulating immune cells, so most cell types exhibit a broad suite of antimicrobial defenses. Although obvious qualitative differences in disease resistance can be observed when multiple specimens are compared (allowing classification as “resistant” or “susceptible” after infection by the same pathogen strain at similar inoculum levels in similar environments), a gradation of quantitative differences in disease resistance is more typically observed between plant strains or genotypes. Plants consistently resist certain pathogens but succumb to others; resistance is usually specific to certain pathogen species or pathogen strains.

Background

Plant disease resistance is crucial to the reliable production of food, and it provides significant reductions in agricultural use of land, water, fuel and other inputs. Plants in both natural and cultivated populations carry inherent disease resistance, but this has not always protected them.

The late blight Irish potato famine of the 1840s was caused by the oomycete Phytophthora infestans. The world’s first mass-cultivated banana cultivar Gros Michel was lost in the 1920s to Panama disease caused by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. The current wheat stem, leaf, and yellow stripe rust epidemics spreading from East Africa into the Indian subcontinent are caused by rust fungi Puccinia graminis and P. striiformis. Other epidemics include Chestnut blight, as well as recurrent severe plant diseases such as Rice blast, Soybean cyst nematode, Citrus canker.[1][2]

Plant pathogens can spread rapidly over great distances, vectored by water, wind, insects, and humans. Across large regions and many crop species, it is estimated that diseases typically reduce plant yields by 10% every year in more developed nations or agricultural systems, but yield loss to diseases often exceeds 20% in less developed settings, an estimated 15% of global crop production.[1]

However, disease control is reasonably successful for most crops. Disease control is achieved by use of plants that have been bred for good resistance to many diseases, and by plant cultivation approaches such as crop rotation, pathogen-free seed, appropriate planting date and plant density, control of field moisture and pesticide use.

Common disease resistance mechanisms

Pre-formed structures and compounds

- Plant cuticle/surface

- Plant cell walls

- Antimicrobial chemicals (for example: glucosides, saponins)

- Antimicrobial proteins

- Enzyme inhibitors

- Detoxifying enzymes that break down pathogen-derived toxins

- Receptors that perceive pathogen presence and activate inducible plant defences[3]

Inducible post-infection plant defenses

- Cell wall reinforcement (callose, lignin, suberin, cell wall proteins)[4]

- Antimicrobial chemicals, including reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide or peroxynitrite, or more complex phytoalexins such as genistein or camalexin

- Antimicrobial proteins such as defensins, thionins, or PR-1

- Antimicrobial enzymes such as chitinases, beta-glucanases, or peroxidases[5]

- Hypersensitive response - a rapid host cell death response associated with defence mediated by “Resistance genes.”(Bryant, Tracy 2008).

Immune system

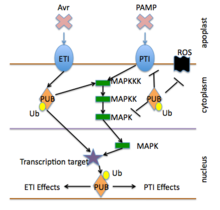

The plant immune system carries two interconnected tiers of receptors, one most frequently sensing molecules outside the cell and the other most frequently sensing molecules inside the cell. Both systems sense the intruder, respond to the intrusion and signal to the rest of the plant and sometimes to neighboring plants that the intruder is present. The two systems detect different types of pathogen molecules and classes of plant receptor proteins.[6][7]

The first tier is primarily governed by pattern recognition receptors that are activated by recognition of evolutionarily conserved pathogen or microbial–associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or MAMPs). Activation of PRRs leads to intracellular signaling, transcriptional reprogramming, and biosynthesis of a complex output response that limits colonization. The system is known as PAMP-Triggered Immunity or as Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI).[7][8]

The second tier, primarily governed by R gene products, is often termed effector-triggered immunity (ETI). ETI is typically activated by the presence of specific pathogen "effectors" and then triggers strong antimicrobial responses (see R gene section below).

In addition to PTI and ETI, plant defenses can be activated by the sensing of damage-associated compounds (DAMP), such as portions of the plant cell wall released during pathogenic infection.

Responses activated by PTI and ETI receptors include ion channel gating, oxidative burst, cellular redox changes, or protein kinase cascades that directly activate cellular changes (such as cell wall reinforcement or antimicrobial production), or activate changes in gene expression that then elevate other defensive responses

Plant immune systems show some mechanistic similarities with the immune systems of insects and mammals, but also exhibit many plant-specific characteristics.[9] The two above-described tiers are central to plant immunity but do not fully describe plant immune systems. In addition, many specific examples of apparent PTI or ETI violate common PTI/ETI definitions, suggesting a need for broadened definitions and/or paradigms.[10]

PAMP-triggered immunity

PAMPs, conserved molecules that inhabit multiple pathogen genera, are referred to as MAMPs by many researchers. The defenses induced by MAMP perception are sufficient to repel most pathogens. However, pathogen effector proteins (see below) are adapted to suppress basal defenses such as PTI. Many receptors for MAMPs (and DAMPs) have been discovered. MAMPs and DAMPs are often detected by transmembrane receptor-kinases that carry LRR or LysM extracellular domains.[6]

Effector triggered immunity

Effector Triggered Immunity (ETI) is activated by the presence of pathogen effectors. The ETI response is reliant on R genes, and is activated by specific pathogen strains. Plant ETI often causes an apoptotic hypersensitive response.

R genes and R proteins

Plants have evolved R genes (resistance genes) whose products mediate resistance to specific virus, bacteria, oomycete, fungus, nematode or insect strains. R gene products are proteins that allow recognition of specific pathogen effectors, either through direct binding or by recognition of the effector's alteration of a host protein.[7] Many R genes encode NB-LRR proteins (proteins with nucleotide-binding and leucine-rich repeat domains, also known as NLR proteins or STAND proteins, among other names). Most plant immune systems carry a repertoire of 100-600 different R gene homologs. Individual R genes have been demonstrated to mediate resistance to specific virus, bacteria, oomycete, fungus, nematode or insect strains. R gene products control a broad set of disease resistance responses whose induction is often sufficient to stop further pathogen growth/spread.

Studied R genes usually confer specificity for particular strains of a pathogen species (those that express the recognized effector). As first noted by Harold Flor in his mid-20th century formulation of the gene-for-gene relationship, a plant R gene has specificity for a pathogen avirulence gene (Avr gene). Avirulence genes are now known to encode effectors. The pathogen Avr gene must have matched specificity with the R gene for that R gene to confer resistance, suggesting a receptor/ligand interaction for Avr and R genes.[9] Alternatively, an effector can modify its host cellular target (or a molecular decoy of that target), and the R gene product (NLR protein) activates defenses when it detects the modified form of the target or decoy.[7]

Effector biology

Effectors are central to the pathogenic or symbiotic potential of microbes and microscopic plant-colonizing animals such as nematodes.[11][12][13] Effectors typically are proteins that are delivered mostly outside the microbe and into the host cell. Effectors manipulate cell physiology and development. As such, effectors offer examples of co-evolution (example: a fungal protein that functions outside of the fungus but inside of plant cells has evolved to take on plant-specific functions). Pathogen host range is determined, among other things, by the presence of appropriate effectors that allow colonization of a particular host.[6] Pathogen-derived effectors are a powerful tool to identify host functions that are important in disease. Apparently most effectors function to manipulate host physiology to allow disease to occur. Well-studied bacterial plant pathogens typically express a few dozen effectors, often delivered into the host by a Type III secretion apparatus.[11] Fungal, oomycete and nematode plant pathogens apparently express a few hundred effectors.[12][13]

So-called "core" effectors are defined operationally by their wide distribution across the population of a particular pathogen and their substantial contribution to pathogen virulence. Genomics can be used to identify core effectors, which can then be used to discover new R gene alleles, which can be used in plant breeding for disease resistance.

RNA silencing and systemic acquired resistance elicited by prior infections

Against viruses, plants often induce pathogen-specific gene silencing mechanisms mediated by RNA interference. This is a form of adaptive immunity.

Plant immune systems also can respond to an initial infection in one part of the plant by physiologically elevating the capacity for a successful defense response in other parts. Such responses include systemic acquired resistance, largely mediated by salicylic acid-dependent pathways, and induced systemic resistance, largely mediated by jasmonic acid-dependent pathways.

Species-level resistance

In a small number of cases, plant genes are effective against an entire pathogen species, even though that species that is pathogenic on other genotypes of that host species. Examples include barley MLO against powdery mildew, wheat Lr34 against leaf rust and wheat Yr36 against stripe rust. An array of mechanisms for this type of resistance may exist depending on the particular gene and plant-pathogen combination. Other reasons for effective plant immunity can include a lack of coadaptation (the pathogen and/or plant lack multiple mechanisms needed for colonization and growth within that host species), or a particularly effective suite of pre-formed defenses.[citation needed]

Signaling mechanisms

Perception of pathogen presence

Plant defense signaling is activated by the pathogen-detecting receptors that are described in an above section.[6] The activated receptors frequently elicit reactive oxygen and nitric oxide production, calcium, potassium and proton ion fluxes, altered levels of salicylic acid and other hormones and activation of MAP kinases and other specific protein kinases.[9] These events in turn typically lead to the modification of proteins that control gene transcription, and the activation of defense-associated gene expression.[8]

Transcription factors and the hormone response

Numerous genes and/or proteins as well as other molecules have been identified that mediate plant defense signal transduction.[14][15] Cytoskeleton and vesicle trafficking dynamics help to orient plant defense responses toward the point of pathogen attack.

Mechanisms of transcription factors and hormones

Plant immune system activity is regulated in part by signaling hormones such as:[16]

There can be substantial cross-talk among these pathways.[16]

Regulation by degradation

As with many signal transduction pathways, plant gene expression during immune responses can be regulated by degradation. This often occurs when hormone binding to hormone receptors stimulates ubiquitin-associated degradation of repressor proteins that block expression of certain genes. The net result is hormone-activated gene expression. Examples:[17]

- Auxin: binds to receptors that then recruit and degrade repressors of transcriptional activators that stimulate auxin-specific gene expression.

- Jasmonic acid: similar to auxin, except with jasmonate receptors impacting jasmonate-response signaling mediators such as JAZ proteins.

- Gibberellic acid: Gibberellin causes receptor conformational changes and binding and degradation of Della proteins.

- Ethylene: Inhibitory phosphorylation of the EIN2 ethylene response activator is blocked by ethylene binding. When this phosphorylation is reduced, EIN2 protein is cleaved and a portion of the protein moves to the nucleus to activate ethylene-response gene expression.

Ubiquitin and E3 signaling

Ubiquitination plays a central role in cell signaling that regulates processes including protein degradation and immunological response.[18] Although one of the main functions of ubiquitin is to target proteins for destruction, it is also useful in signaling pathways, hormone release, apoptosis and translocation of materials throughout the cell. Ubiquitination is a component of several immune responses. Without ubiquitin's proper functioning, the invasion of pathogens and other harmful molecules would increase dramatically due to weakened immune defenses.[18]

E3 signaling

The E3 Ubiquitin ligase enzyme is a main component that provides specificity in protein degradation pathways, including immune signaling pathways.[17] The E3 enzyme components can be grouped by which domains they contain and include several types.[19] These include the Ring and U-box single subunit, HECT, and CRLs.[20][21] Plant signaling pathways including immune responses are controlled by several feedback pathways, which often include negative feedback; and they can be regulated by De-ubiquitination enzymes, degradation of transcription factors and the degradation of negative regulators of transcription.[17][22]

Plant breeding for disease resistance

Plant breeders emphasize selection and development of disease-resistant plant lines. Plant diseases can also be partially controlled by use of pesticides and by cultivation practices such as crop rotation, tillage, planting density, disease-free seeds and cleaning of equipment, but plant varieties with inherent (genetically determined) disease resistance are generally preferred.[2] Breeding for disease resistance began when plants were first domesticated. Breeding efforts continue because pathogen populations are under selection pressure for increased virulence, new pathogens appear, evolving cultivation practices and changing climate can reduce resistance and/or strengthen pathogens, and plant breeding for other traits can disrupt prior resistance.[23] A plant line with acceptable resistance against one pathogen may lack resistance against others.

Breeding for resistance typically includes:

- Identification of plants that may be less desirable in other ways, but which carry a useful disease resistance trait, including wild strains that often express enhanced resistance.

- Crossing of a desirable but disease-susceptible variety to another variety that is a source of resistance.

- Growth of breeding candidates in a disease-conducive setting, possibly including pathogen inoculation. Attention must be paid to the specific pathogen isolates, to address variability within a single pathogen species.

- Selection of disease-resistant individuals that retain other desirable traits such as yield, quality and including other disease resistance traits.[23]

Resistance is termed durable if it continues to be effective over multiple years of widespread use as pathogen populations evolve. "Vertical resistance" is specific to certain races or strains of a pathogen species, is often controlled by single R genes and can be less durable. Horizontal or broad-spectrum resistance against an entire pathogen species is often only incompletely effective, but more durable, and is often controlled by many genes that segregate in breeding populations.[2]

Crops such as potato, apple, banana and sugarcane are often propagated by vegetative reproduction to preserve highly desirable plant varieties, because for these species, outcrossing seriously disrupts the preferred traits. See also asexual propagation. Vegetatively propagated crops may be among the best targets for resistance improvement by the biotechnology method of plant transformation to manage genes that affect disease resistance.[1]

Scientific breeding for disease resistance originated with Sir Rowland Biffen, who identified a single recessive gene for resistance to wheat yellow rust. Nearly every crop was then bred to include disease resistance (R) genes, many by introgression from compatible wild relatives.[1]

GM or transgenic engineered disease resistance

The term GM ("genetically modified") is often used as a synonym of transgenic to refer to plants modified using recombinant DNA technologies. Plants with transgenic/GM disease resistance against insect pests have been extremely successful as commercial products, especially in maize and cotton, and are planted annually on over 20 million hectares in over 20 countries worldwide[24] (see also genetically modified crops). Transgenic plant disease resistance against microbial pathogens was first demonstrated in 1986. Expression of viral coat protein gene sequences conferred virus resistance via small RNAs. This proved to be a widely applicable mechanism for inhibiting viral replication.[25] Combining coat protein genes from three different viruses, scientists developed squash hybrids with field-validated, multiviral resistance. Similar levels of resistance to this variety of viruses had not been achieved by conventional breeding.

A similar strategy was deployed to combat papaya ringspot virus, which by 1994 threatened to destroy Hawaii’s papaya industry. Field trials demonstrated excellent efficacy and high fruit quality. By 1998 the first transgenic virus-resistant papaya was approved for sale. Disease resistance has been durable for over 15 years. Transgenic papaya accounts for ~85% of Hawaiian production. The fruit is approved for sale in the U.S., Canada and Japan.

Potato lines expressing viral replicase sequences that confer resistance to potato leafroll virus were sold under the trade names NewLeaf Y and NewLeaf Plus, and were widely accepted in commercial production in 1999-2001, until McDonald's Corp. decided not to purchase GM potatoes and Monsanto decided to close their NatureMark potato business.[26] NewLeaf Y and NewLeaf Plus potatoes carried two GM traits, as they also expressed Bt-mediated resistance to Colorado potato beetle.

No other crop with engineered disease resistance against microbial pathogens had reached the market by 2013, although more than a dozen were in some state of development and testing.

| Publication year | Crop | Disease resistance | Mechanism | Development status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | Tomato | Bacterial spot | R gene from pepper | 8 years of field trials |

| 2012 | Rice | Bacterial blight and bacterial streak | Engineered E gene | Laboratory |

| 2012 | Wheat | Powdery mildew | Overexpressed R gene from wheat | 2 years of field trials at time of publication |

| 2011 | Apple | Apple scab fungus | Thionin gene from barley | 4 years of field trials at time of publication |

| 2011 | Potato | Potato virus Y | Pathogen-derived resistance | 1 year of field trial at time of publication |

| 2010 | Apple | Fire blight | Antibacterial protein from moth | 12 years of field trials at time of publication |

| 2010 | Tomato | Multibacterial resistance | PRR from Arabidopsis | Laboratory scale |

| 2010 | Banana | Xanthomonas wilt | Novel gene from pepper | Now in field trial |

| 2009 | Potato | Late blight | R genes from wild relatives | 3 years of field trials |

| 2009 | Potato | Late blight | R gene from wild relative | 2 years of field trials at time of publication |

| 2008 | Potato | Late blight | R gene from wild relative | 2 years of field trials at time of publication |

| 2008 | Plum | Plum pox virus | Pathogen-derived resistance | Regulatory approvals, no commercial sales |

| 2005 | Rice | Bacterial streak | R gene from maize | Laboratory |

| 2002 | Barley | Stem rust | Resting lymphocyte kinase (RLK) gene from resistant barley cultivar | Laboratory |

| 1997 | Papaya | Ring spot virus | Pathogen-derived resistance | Approved and commercially sold since 1998, sold into Japan since 2012 |

| 1995 | Squash | Three mosaic viruses | Pathogen-derived resistance | Approved and commercially sold since 1994 |

| 1993 | Potato | Potato virus X | Mammalian interferon-induced enzyme | 3 years of field trials at time of publication |

PRR transfer

Research aimed at engineered resistance follows multiple strategies. One is to transfer useful PRRs into species that lack them. Identification of functional PRRs and their transfer to a recipient species that lacks an orthologous receptor could provide a general pathway to additional broadened PRR repertoires. For example, the Arabidopsis PRR EF-Tu receptor (EFR) recognizes the bacterial translation elongation factor EF-Tu. Research performed at Sainsbury Laboratory demonstrated that deployment of EFR into either Nicotiana benthamianaor Solanum lycopersicum (tomato), which cannot recognize EF-Tu, conferred resistance to a wide range of bacterial pathogens. EFR expression in tomato was especially effective against the widespread and devastating soil bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum.[27] Conversely, the tomato PRR Verticillium 1 (Ve1) gene can be transferred from tomato to Arabidopsis, where it confers resistance to race 1 Verticillium isolates.[1]

Stacking

The second strategy attempts to deploy multiple NLR genes simultaneously, a breeding strategy known as stacking. Cultivars generated by either DNA-assisted molecular breeding or gene transfer will likely display more durable resistance, because pathogens would have to mutate multiple effector genes. DNA sequencing allows researchers to functionally “mine” NLR genes from multiple species/strains.[1]

The avrBs2 effector gene from Xanthomona perforans is the causal agent of bacterial spot disease of pepper and tomato. The first “effector-rationalized” search for a potentially durable R gene followed the finding that avrBs2 is found in most disease-causing Xanthomonas species and is required for pathogen fitness. The Bs2 NLR gene from the wild pepper, Capsicum chacoense, was moved into tomato, where it inhibited pathogen growth. Field trials demonstrated robust resistance without bactericidal chemicals. However, rare strains of Xanthomonas overcame Bs2-mediated resistance in pepper by acquisition of avrBs2 mutations that avoid recognition but retain virulence. Stacking R genes that each recognize a different core effector could delay or prevent adaptation.[1]

More than 50 loci in wheat strains confer disease resistance against wheat stem, leaf and yellow stripe rust pathogens. The Stem rust 35 (Sr35) NLR gene, cloned from a diploid relative of cultivated wheat, Triticum monococcum, provides resistance to wheat rust isolate Ug99. Similarly, Sr33, from the wheat relative Aegilops tauschii, encodes a wheat ortholog to barley Mla powdery mildew–resistance genes. Both genes are unusual in wheat and its relatives. Combined with the Sr2 gene that acts additively with at least Sr33, they could provide durable disease resistance to Ug99 and its derivatives.[1]

Executor genes

Another class of plant disease resistance genes opens a “trap door” that quickly kills invaded cells, stopping pathogen proliferation. Xanthomonas and Ralstonia transcription activator–like (TAL) effectors are DNA-binding proteins that activate host gene expression to enhance pathogen virulence. Both the rice and pepper lineages independently evolved TAL-effector binding sites that instead act as an executioner that induces hypersensitive host cell death when up-regulated. Xa27 from rice and Bs3 and Bs4c from pepper, are such “executor” (or "executioner") genes that encode non-homologous plant proteins of unknown function. Executor genes are expressed only in the presence of a specific TAL effector.[1]

Engineered executor genes were demonstrated by successfully redesigning the pepper Bs3 promoter to contain two additional binding sites for TAL effectors from disparate pathogen strains. Subsequently, an engineered executor gene was deployed in rice by adding five TAL effector binding sites to the Xa27 promoter. The synthetic Xa27 construct conferred resistance against Xanthomonas bacterial blight and bacterial leaf streak species.[1]

Host susceptibility alleles

Most plant pathogens reprogram host gene expression patterns to directly benefit the pathogen. Reprogrammed genes required for pathogen survival and proliferation can be thought of as “disease-susceptibility genes.” Recessive resistance genes are disease-susceptibility candidates. For example, a mutation disabled an Arabidopsis gene encoding pectate lyase (involved in cell wall degradation), conferring resistance to the powdery mildew pathogen Golovinomyces cichoracearum. Similarly, the Barley MLO gene and spontaneously mutated pea and tomato MLO orthologs also confer powdery mildew resistance.[1]

Lr34 is a gene that provides partial resistance to leaf and yellow rusts and powdery mildew in wheat. Lr34 encodes an adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–binding cassette (ABC) transporter. The dominant allele that provides disease resistance was recently found in cultivated wheat (not in wild strains) and, like MLO provides broad-spectrum resistance in barley.[1]

Natural alleles of host translation elongation initiation factors eif4e and eif4g are also recessive viral-resistance genes. Some have been deployed to control potyviruses in barley, rice, tomato, pepper, pea, lettuce and melon. The discovery prompted a successful mutant screen for chemically induced eif4e alleles in tomato.[1]

Natural promoter variation can lead to the evolution of recessive disease-resistance alleles. For example, the recessive resistance gene xa13 in rice is an allele of Os-8N3. Os-8N3 is transcriptionally activated byXanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae strains that express the TAL effector PthXo1. The xa13 gene has a mutated effector-binding element in its promoter that eliminates PthXo1 binding and renders these lines resistant to strains that rely on PthXo1. This finding also demonstrated that Os-8N3 is required for susceptibility.[1]

Xa13/Os-8N3 is required for pollen development, showing that such mutant alleles can be problematic should the disease-susceptibility phenotype alter function in other processes. However, mutations in the Os11N3 (OsSWEET14) TAL effector–binding element were made by fusing TAL effectors to nucleases (TALENs). Genome-edited rice plants with altered Os11N3 binding sites remained resistant to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, but still provided normal development function.[1]

Gene silencing

RNA silencing-based resistance is a powerful tool for engineering resistant crops. The advantage of RNAi as a novel gene therapy against fungal, viral and bacterial infection in plants lies in the fact that it regulates gene expression via messenger RNA degradation, translation repression and chromatin remodelling through small non-coding RNAs. Mechanistically, the silencing processes are guided by processing products of the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) trigger, which are known as small interfering RNAs and microRNAs.[28]

Host range

Among the thousands of species of plant pathogenic microorganisms, only a small minority have the capacity to infect a broad range of plant species. Most pathogens instead exhibit a high degree of host-specificity. Non-host plant species are often said to express non-host resistance. The term host resistance is used when a pathogen species can be pathogenic on the host species but certain strains of that plant species resist certain strains of the pathogen species. The causes of host resistance and non-host resistance can overlap. Pathogen host range is determined, among other things, by the presence of appropriate effectors that allow colonization of a particular host.[6] Pathogen host range can change quite suddenly if, for example, the pathogen's capacity to synthesize a host-specific toxin or effector is gained by gene shuffling/mutation, or by horizontal gene transfer.[29] [30]

Epidemics and population biology

Native populations are often characterized by substantial genotype diversity and dispersed populations (growth in a mixture with many other plant species). They also have undergone of plant-pathogen coevolution. Hence as long as novel pathogens are not introduced/do not evolve, such populations generally exhibit only a low incidence of severe disease epidemics.[31]

Monocrop agricultural systems provide an ideal environment for pathogen evolution, because they offer a high density of target specimens with similar/identical genotypes.[31] The rise in mobility stemming from modern transportation systems provides pathogens with access to more potential targets.[31] Climate change can alter the viable geographic range of pathogen species and cause some diseases to become a problem in areas where the disease was previously less important.[31]

These factors make modern agriculture more prone to disease epidemics. Common solutions include constant breeding for disease resistance, use of pesticides, use of border inspections and plant import restrictions, maintenance of significant genetic diversity within the crop gene pool (see crop diversity), and constant surveillance to accelerate initiation of appropriate responses. Some pathogen species have much greater capacity to overcome plant disease resistance than others, often because of their ability to evolve rapidly and to disperse broadly.[31]

See also

- Disease resistance in fruit and vegetables

- Gene-for-gene relationship

- Plant defense against herbivory

- Plant pathology

- Plant use of endophytic fungi in defense

- Systemic acquired resistance

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Dangl, J. L.; Horvath, D. M.; Staskawicz, B. J. (2013). "Pivoting the Plant Immune System from Dissection to Deployment". Science. 341 (6147): 746. doi:10.1126/science.1236011.

- ^ a b c Agrios, George N. (2005). Plant Pathology, Fifth Edition. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0120445653.

- ^ Lutz, Diana (2012). Key part of plants' rapid response system revealed. Washington University in St. Louis.

- ^ Dadakova, K.; Havelkova, M.; Kurkova, B.; Tlolkova, I.; Kasparovsky, T.; Zdrahal, Z.; Lochman, J. (2015-04-24). "Proteome and transcript analysis of Vitis vinifera cell cultures subjected to Botrytis cinerea infection". Journal of Proteomics. 119: 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2015.02.001.

- ^ Dadakova, K.; Havelkova, M.; Kurkova, B.; Tlolkova, I.; Kasparovsky, T.; Zdrahal, Z.; Lochman, J. (2015-04-24). "Proteome and transcript analysis of Vitis vinifera cell cultures subjected to Botrytis cinerea infection". Journal of Proteomics. 119: 143–153. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2015.02.001.

- ^ a b c d e Dodds, P. N.; Rathjen, J. P. (2010). "Plant immunity: Towards an integrated view of plant–pathogen interactions". Nature Reviews Genetics. 11 (8): 539. doi:10.1038/nrg2812.

- ^ a b c d Jones, J. D.; Dangl, J.L. (2006). "The plant immune system". Nature. 444 (7117): 323–329. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..323J. doi:10.1038/nature05286. PMID 17108957.

- ^ a b Li, B.; Meng, X.; Shan, L.; He, P. (2016). "Transcriptional Regulation of Pattern-Triggered Immunity in Plants". Cell Host Microbe. 19 (5): 641–650. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.011. PMID 27173932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Nurnberger, T.; Brunner, F., Kemmerling, B., and Piater, L.; Kemmerling, B; Piater, L (2004). "Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences". Immunological Reviews. 198: 249–266. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0119.x. PMID 15199967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thomma, B.; Nurnberger, T.; Joosten, M. (2011). "Of PAMPs and Effectors: The Blurred PTI-ETI Dichotomy". The Plant Cell. 23 (4): 15. doi:10.1105/tpc.110.082602. PMC 3051239. PMID 21278123.

- ^ a b Lindeberg, M; Cunnac S, Collmer A (2012). "Pseudomonas syringae type III effector repertoires: last words in endless arguments". Trends Microbiol. 20: 199–208. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.003. PMID 22341410.

- ^ a b Rafiqi, M; Ellis JG, Ludowici VA, Hardham AR, Dodds PN (2012). "Challenges and progress towards understanding the role of effectors in plant-fungal interactions". Curr Opin Plant Biol. 15: 477–482. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2012.05.003. PMID 22658704.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hewezi, T; Baum T (2013). "Manipulation of plant cells by cyst and root-knot nematode effectors". Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 26: 9–16. doi:10.1094/MPMI-05-12-0106-FI. PMID 22809272.

- ^ Hammond-Kosack KE; Parker JE (Apr 2003). "Deciphering plant-pathogen communication: fresh perspectives for molecular resistance breeding". Curr Opin Biotechnol. 14 (2): 177–193. doi:10.1016/s0958-1669(03)00035-1. PMID 12732319.

- ^ Dadakova, Katerina; Klempova, Jitka; Jendrisakova, Tereza; Lochman, Jan; Kasparovsky, Tomas (2013-12-01). "Elucidation of signaling molecules involved in ergosterol perception in tobacco". Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 73: 121–127. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.09.009.

- ^ a b Moore, J. W.; Loake, G. J.; Spoel, S. H. (12 August 2011). "Transcription Dynamics in Plant Immunity". The Plant Cell. 23 (8): 2809–2820. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.087346. PMC 3180793. PMID 21841124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Sadanandom, Ari; Bailey, Mark; Ewan, Richard; Lee, Jack; Nelis, Stuart (1 October 2012). "The ubiquitin-proteasome system: central modifier of plant signalling". New Phytologist. 196 (1): 13–28. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04266.x. PMID 22897362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Trujillo, M; Shirasu, K (August 2010). "Ubiquitination in plant immunity". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 13 (4): 402–8. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.002. PMID 20471305.

- ^ Craig, A.; Ewan, R.; Mesmar, J.; Gudipati, V.; Sadanandom, A. (10 March 2009). "E3 ubiquitin ligases and plant innate immunity". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (4): 1123–1132. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp059. PMID 19276192.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moon, J. (1 December 2004). "The Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway and Plant Development". The Plant Cell Online. 16 (12): 3181–3195. doi:10.1105/tpc.104.161220.

- ^ Trujillo, Marco; Shirasu, Ken (1 August 2010). "Ubiquitination in plant immunity". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 13 (4): 402–408. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.002. PMID 20471305.

- ^ Shirsekar, Gautam; Dai, Liangying; Hu, Yajun; Wang, Xuejun; Zeng, Lirong; Wang, Guo-Liang; Hu, Yajun; Wang, Xuejun; Zeng, Lirong; Wang, Guo-Liang (2010). "Role of Ubiquitination in Plant Innate Immunity and Pathogen Virulence". Journal of Plant Biology. 53 (1): 10–18. doi:10.1007/s12374-009-9087-x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stuthman, DD; Leonard, KJ; Miller-Garvin, J (2007). "Breeding crops for durable resistance to disease". Advances in Agronomy: 319–367.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tabashnik, Bruce E.; Brevault, Thierry; Carriere, Yves (2013). "Insect resistance to Bt crops: lessons from the first billion acres". Nature Biotechnology. 31: 510–521. doi:10.1038/nbt.2597.

- ^ Kavanagh, T. A.; Spillane, C. (1995-02-01). "Strategies for engineering virus resistance in transgenic plants". Euphytica. 85 (1–3): 149–158. doi:10.1007/BF00023943. ISSN 0014-2336.

- ^ Kaniewski, Wojciech K.; Thomas, Peter E. (2004). "The Potato Story". AgBioForum. 7 (1&2): 41–46.

- ^ Lacombe et al., 2010 Interfamily transfer of a plant pattern-recognition receptor confers broad-spectrum bacterial resistance, Nature Biotech 28, 365–369

- ^ Karthikeyan, A.; Deivamani, M.; Shobhana, V. G.; Sudha, M.; Anandhan, T. (2013). "RNA interference: Evolutions and applications in plant disease management". Archives of Phytopathology and Plant Protection. 46 (12): 1430. doi:10.1080/03235408.2013.769315.

- ^ Bettgenhaeuser, J; Gilbert B, Ayliffe M, Moscou MJ (2014). "Nonhost resistance to rust pathogens - a continuation of continua". Front Plant Sci. 5: 664. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00664. PMID 25566270.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Restrepo, S; Tabima JF, Mideros MF, Grünwald NJ, Matute DR (2014). "Speciation in fungal and oomycete plant pathogens". Annu Rev Phytopathol. 52: 289–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-050056. PMID 24906125.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e McDonald, B. A.; Linde, C (2002). "Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 40: 349–79. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120501.101443. PMID 12147764.

Further reading

- Lucas, J.A., "Plant Defence." Chapter 9 in Plant Pathology and Plant Pathogens, 3rd ed. 1998 Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03046-1

- Hammond-Kosack, K. and Jones, J.D.G. "Responses to plant pathogens." In: Buchanan, Gruissem and Jones, eds. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants, Second Edition. 2015. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken, NJ. ISBN 9780470714218

- Dodds, P.; Rathjen, J. (2010). "Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant–pathogen interactions". Nature Reviews Genetics. 11: 539. doi:10.1038/nrg2812.

- Schumann, G. Plant Diseases: Their Biology and Social Impact. 1991 APS Press, St. Paul, MN. ISBN 0890541167