Plinian eruption

Plinian eruptions or Vesuvian eruptions are volcanic eruptions marked by their similarity to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which destroyed the ancient Roman cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii. The eruption was described in a letter written by Pliny the Younger, after the death of his uncle Pliny the Elder.

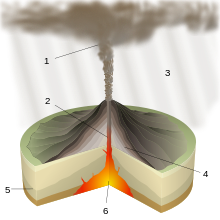

Plinian/Vesuvian eruptions are marked by columns of volcanic debris and hot gases ejected high into the stratosphere, the second layer of Earth's atmosphere. The key characteristics are ejection of large amount of pumice and very powerful continuous gas-driven eruptions. According to the Volcanic Explosivity Index, Plinian eruptions have a VEI of 4, 5 or 6, sub-Plinian 3 or 4, and ultra-Plinian 6, 7 or 8.

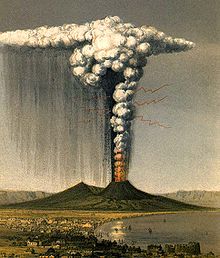

Short eruptions can end in less than a day, but longer events can take several days or even months. The longer eruptions begin with production of clouds of volcanic ash, sometimes with pyroclastic surges. The amount of magma erupted can be so large that it depletes the magma chamber below, causing the top of the volcano to collapse, resulting in a caldera. Fine ash and pulverized pumice can deposit over large areas. Plinian eruptions are often accompanied by loud noises, such as those generated by the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa. The sudden discharge of electrical charges accumulated in the air around the ascending column of volcanic ashes also often causes lightning strikes as depicted by the English geologist George Julius Poulett Scrope in his painting of 1822.

The lava is usually rhyolitic and rich in silicates. Basaltic, low-silicate lavas are unusual for Plinian eruptions; the most recent basaltic example is the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera on New Zealand's North Island.[citation needed]

Pliny's description

Pliny described his uncle's involvement from the first observation of the eruption:[1]

On August 24th, about one in the afternoon, my mother desired him to observe a cloud which appeared of a very unusual size and shape. He had just taken a turn in the sun and, after bathing himself in cold water, and making a light luncheon, gone back to his books: he immediately arose and went out upon a rising ground from whence he might get a better sight of this very uncommon appearance. A cloud, from which mountain was uncertain, at this distance (but it was found afterwards to come from Mount Vesuvius), was ascending, the appearance of which I cannot give you a more exact description of than by likening it to that of a pine tree, for it shot up to a great height in the form of a very tall trunk, which spread itself out at the top into a sort of branches; occasioned, I imagine, either by a sudden gust of air that impelled it, the force of which decreased as it advanced upwards, or the cloud itself being pressed back again by its own weight, expanded in the manner I have mentioned; it appeared sometimes bright and sometimes dark and spotted, according as it was either more or less impregnated with earth and cinders. This phenomenon seemed to a man of such learning and research as my uncle extraordinary and worth further looking into.

— Sixth Book of Letters, Letter 16, translation by William Melmoth

Pliny the Elder set out to rescue the victims from their perilous position on the shore of the Bay of Naples, and launched his galleys, crossing the bay to Stabiae (near the modern town of Castellammare di Stabia). Pliny the Younger provided an account of his death, and suggested that he collapsed and died through inhaling poisonous gases emitted from the volcano. His body was found interred under the ashes of the eruption with no apparent injuries on 26 August, after the plume had dispersed, confirming asphyxiation or poisoning.

Examples

- The June 2009 eruption of Sarychev Peak in Russia.

- The 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in Zambales, Central Luzon, Philippines.

- The 1982 eruption of El Chichón in Chiapanecan Volcanic Arc, Chiapas, Mexico.

- The 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington in the United States.

- The 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera in New Zealand.

- The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Sunda Strait, Indonesia.

- The 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in the island of Sumbawa, Indonesia.

- The 1667 and 1739 eruptions of Mount Tarumae in Hokkaido, Japan.[2]

- The 180 AD Lake Taupo eruption in New Zealand.

- The 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii, Italy. It was the prototypical Plinian eruption.

- The 400s BC eruption of the Bridge River Vent in British Columbia, Canada.

- The 1645 BC eruption of Thera in the south Aegean Sea, Greece.

- The 4860 BC eruption forming Crater Lake in Oregon, United States.

- The Long Valley Caldera eruption in Eastern California, United States, which happened over 760,000 years ago.

Ultra-Plinian

According to the Volcanic Explosivity Index, a VEI of 6 to 8 is classified as "ultra-Plinian". Eruptions of this type are defined by ash plumes over 25 km (16 mi) high and a volume of erupted material 10 km3 (2 cu mi) to 1,000 km3 (200 cu mi) in size. Eruptions in the ultra-Plinian category include the Lava Creek eruption of the Yellowstone Caldera (approx 640,000 years ago, VEI 8), Lake Toba (approx 74000 years ago, VEI 8), Tambora (1815, VEI 7), Krakatoa (1883, VEI 6), Akahoya eruption of Kikai Caldera, Japan, and the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption in the Philippines (VEI 6).[3][4]

See also

- Peléan eruption, related to the explosive eruptions of the Mount Pelée

- Types of volcanic eruptions

- List of largest volcanic eruptions

References

- ^ Pliny's Letters. pp. 473–481.

- ^ Enlightenment activities for improvement on disasters from Tarumae Volcano, Japan, Cities on Volcanoes 4, 23–27 January 2006

- ^ "How Volcanoes Work: Variability of Eruptions". San Diego State University. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ^ Maeno F, Taniguchi H. (2005). Eruptive History of Satsuma Iwo-jima Island, Kikai Caldera, after a 6.5ka caldera-forming eruption. Bulletin of the Volcanological Society of Japan. 50(2):71–85. ISSN 0453-4360.