Port Mercer, New Jersey

Port Mercer, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

The historic Port Mercer Canal House | |

| Coordinates: 40°18′15″N 74°41′06″W / 40.30417°N 74.68500°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

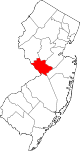

| County | Mercer |

| Township | Lawrence, Princeton and West Windsor |

| Elevation | 56 ft (17 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 879438[1] |

Port Mercer is an unincorporated community located where the municipal boundaries of Lawrence Township, Princeton and West Windsor Township intersect in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is the location of the historic Port Mercer Canal House along the Delaware and Raritan Canal.

Port Mercer developed starting in the 1830s with the construction of the Delaware & Raritan Canal. It represents one of West Windsor's historic hamlets, and several mid-1800s residences still populate the community. The hamlet thrived from the 1830s until the mid-late 19th century, when the current Northeast Corridor rail line relocated from next to the canal to its current position. The community still houses several historic residences, including the former Port Mercer Inn.

History

[edit]Early history (1777-1834)

[edit]The area that is now Port Mercer was sparsely populated during the American Revolution, and may have been known as the "Great Meadow."[2][3] In 1777, George Washington marched through the area with his troops prior to the Battle of Princeton, during the Ten Crucial Days. Until the 1830s, the area, like much of central New Jersey, was isolated and remained sparse in population.[4] The little settlement there was in the region was farmland concentrated near Clarksville, New Jersey and Brunswick Pike (now US Route 1).[5]

Economic growth (1834-1849)

[edit]The area's isolation ended with the 1834 opening of the Delaware and Raritan Canal.[4] The growing commercial traffic from the canal, as well as the construction of the Camden and Amboy Railroad along the canal, spurred the growth of a hamlet called Clarksville Basin, centered on a small turning basin.[2][5] The basin served as an economic outlet for local farms, and provided locals with outside amenities such as coal.[5] A swing bridge was constructed over the canal in the 1830s. A house for the bridge-tender was constructed in 1833-1834, but was abandoned and replaced by a new structure in the 1840s when the road's alignment was changed. The original canal house may have survived until the 20th century, and was remembered by locals as "the spring house."[5]

A number of houses were constructed between 1834 and 1850, including the Uhl-Keith and Uhl houses, which may have been rented out to tenants such as the Stout and Fagan families.[6][7] In 1835, Charles Gillingham opened a lumber yard in the hamlet and began selling lime with Joseph Decou Jr. By 1840, Joseph Gillingham owned lime kilns, a few residences, and a store house. From about 1840 to 1848, Alfred Applegate was the likely owner a general store for the community.[2][5] Sometime before the decade's end, Lewis Gordon had built the Gordon House.[8] He also likely built the Furman-Marchesi house around the same time.[9] In 1849, a post office was established, operated by postmaster John A. S. Crater, who had bought a tract of land containing the aforementioned houses in the community from Joseph Gillingham.[2][10]

Commercial development (1849-1892)

[edit]By this point, the hamlet's name had become Port Mercer, having also been known as Port Windsor for some time. The same year, Crater also established a steam-powered sawmill which may have provided the hamlet with lumber. Crater owned a number of other establishments in the community, including a coal yard, an ice house, and a number of barns. He also operated a blacksmith shop, a shoe store, and came to run the general store that Applegate had operated.[2] The store itself went through multiple local owners in the 19th century.[2][11] Crater built the Port Mercer Inn on the tract he had purchased from Gillingham sometime before 1858. The Inn served both rail and canal traffic, and local rumor suggested it employed prostitutes from Trenton.[10]

Sometime between 1840 and 1860, the Gordon-Northrup House was constructed on the tract Crater had purchased. It was owned by Richard Cook until 1868, when the parcel containing the house was sold to the local Gordon family.[12] The remaining Cook land included a grain house, a barn, and the Uhl-Keith and Uhl houses.[10] Locals would often try to profit from the traffic on the canal through "a well-timed delay in opening the swing bridge." This would sometimes entangle the tow lines of mules and draw them into the water, where local boys would rescue them for a reward. Locals also set up bottles and other targets along the canal in the hopes that bargemen would recreationally throw coal at them.[2]

Decline and preservation (1892-present)

[edit]As railroad commerce increased and aligned itself to the present-day route of the Northeast Corridor in 1863, the canal declined in commercial use, ceasing to be profitable in 1892.[2][4] Economic activity declined in Port Mercer declined during this period.[5] In the late 19th century, racehorses were raised by John F. Schanck on a farm in the community.[2] The canal eventually closed in 1933 and was taken over by the state.[4] A number of drownings and car crashed into the canal occurred in the early 20th century, and on two separate occasions murder victims were dumped into the water. A sense of "neighborhood" persisted in the community, which had been less economically harmed by the canal's decline than neighboring Princeton Basin.[2]

The Port Mercer Inn was likely still functioning in 1871,[10] but was eventually turned into a residence by Richard Cook, who rented it out to the family of future bridge-tender John Arrowsmith.[5] In 1898, the Cook properties passed to David and Kate Flock and then to Charles H. Mather. Mather became a prominent resident of the town, operating the general store, where he sold farm machinery, and an adjacent coal yard until 1915.[10] In 1951,[10] the store eventually passed to the Harlow family, which tore it down in the 1950s, replacing it with a flower garden.[11] The canal house remained a private residence of the Arrowsmith family until 1965. It was used to house New Jersey Water Supply Authority workers throughout the next decade. In 1973, many of Port Mercer's buildings were placed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the following year, the canal was designated a state park.[13]

Widespread farming in the Port Mercer area continued until the construction of residential and commercial projects in the late 20th century. Many of Port Mercer's historic buildings remain standing, and are still used as private residencies.[2][6][7] The Lawrence Historical Society restored the canal house in 1978 and operates it as a museum.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Port Mercer". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Port Mercer". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ Lee, Francis Bazley (1907). Genealogical and Personal Memorial of Mercer County, New Jersey, Volume 1. p. 72.

- ^ a b c d "Port Mercer Canal House". Lawrence Historical. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "THE STORY OF PORT MERCER". D&R Canal State Park. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Uhl-Keith House". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Uhl House". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ "Gordon House". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ "Furman-Marchesi House". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Port Mercer Inn". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Port Mercer Store". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ "Gordon-Northrop House". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Port Mercer Canal House". THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WEST WINDSOR. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

External links

[edit]