Quarkonium

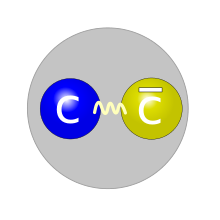

In particle physics, quarkonium (from quark + onium, pl. quarkonia) designates a flavorless meson whose constituents are a quark and its own antiquark. Examples of quarkonia are the J/ψ meson (an example of charmonium,

c

c

) and the

ϒ

meson (bottomonium,

b

b

). Because of the high mass of the top quark, toponium does not exist, since the top quark decays through the electroweak interaction before a bound state can form. Usually quarkonium refers only to charmonium and bottomonium, and not to any of the lighter quark–antiquark states. This usage is because the lighter quarks (up, down, and strange) are much less massive than the heavier quarks, and so the physical states actually seen in experiments (η, η′, and π0 mesons) are quantum mechanical mixtures of the light quark states. The much larger mass differences between the charm and bottom quarks and the lighter quarks results in states that are well defined in terms of a quark–antiquark pair of a given flavor.

Charmonium states

In the following table, the same particle can be named with the spectroscopic notation or with its mass. In some cases excitation series are used: Ψ' is the first excitation of Ψ (for historical reasons, this one is called J/ψ particle); Ψ" is a second excitation, and so on. That is, names in the same cell are synonymous.

Some of the states are predicted, but have not been identified; others are unconfirmed. The quantum numbers of the X(3872) particle have been measured recently by the LHCb experiment at CERN[1] . This measurement shed some light on its identity, excluding the third option among the three envised, which are :

- a candidate for the 11D2 state;

- a charmonium hybrid state;

- a molecule.

In 2005, the BaBar experiment announced the discovery of a new state: Y(4260).[2][3] CLEO and Belle have since corroborated these observations. At first, Y(4260) was thought to be a charmonium state, but the evidence suggests more exotic explanations, such as a D "molecule", a 4-quark construct, or a hybrid meson.

| Term symbol n2S + 1LJ | IG(JPC) | Particle | mass (MeV/c2) [1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11S0 | 0+(0−+) | ηc(1S) | 2980.3±1.2 |

| 13S1 | 0−(1−−) | J/ψ(1S) | 3096.916±0.011 |

| 11P1 | 0−(1+−) | hc(1P) | 3525.93±0.27 |

| 13P0 | 0+(0++) | χc0(1P) | 3414.75±0.31 |

| 13P1 | 0+(1++) | χc1(1P) | 3510.66±0.07 |

| 13P2 | 0+(2++) | χc2(1P) | 3556.20±0.09 |

| 21S0 | 0+(0−+) | ηc(2S), or η′ c |

3637±4 |

| 23S1 | 0−(1−−) | ψ(3686) | 3686.09±0.04 |

| 11D2 | 0+(2−+) | ηc2(1D)† | |

| 13D1 | 0−(1−−) | ψ(3770) | 3772.92±0.35 |

| 13D2 | 0−(2−−) | ψ2(1D) | |

| 13D3 | 0−(3−−) | ψ3(1D)† | |

| 21P1 | 0−(1+−) | hc(2P)† | |

| 23P0 | 0+(0++) | χc0(2P)† | |

| 23P1 | 0+(1++) | χc1(2P)† | |

| 23P2 | 0+(2++) | χc2(2P)† | |

| ???? | 1++† | X(3872) | 3872.2±0.8 |

| ???? | ??(1−−) | Y(4260) | 4263+8 −9 |

Notes:

- * Needs confirmation.

- † Predicted, but not yet identified.

- † Interpretation as a 1−− charmonium state not favored.

Bottomonium states

In the following table, the same particle can be named with the spectroscopic notation or with its mass.

Some of the states are predicted, but have not been identified; others are unconfirmed.

| Term symbol n2S+1LJ | IG(JPC) | Particle | mass (MeV/c2)[2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11S0 | 0+(0−+) | ηb(1S) | 9390.9±2.8 |

| 13S1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(1S) | 9460.30±0.26 |

| 11P1 | 0−(1+−) | hb(1P) | |

| 13P0 | 0+(0++) | χb0(1P) | 9859.44±0.52 |

| 13P1 | 0+(1++) | χb1(1P) | 9892.76±0.40 |

| 13P2 | 0+(2++) | χb2(1P) | 9912.21±0.40 |

| 21S0 | 0+(0−+) | ηb(2S) | |

| 23S1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(2S) | 10023.26±0.31 |

| 11D2 | 0+(2−+) | ηb2(1D) | |

| 13D1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(1D) | |

| 13D2 | 0−(2−−) | Υ2(1D) | 10161.1±1.7 |

| 13D3 | 0−(3−−) | Υ3(1D) | |

| 21P1 | 0−(1+−) | hb(2P) | |

| 23P0 | 0+(0++) | χb0(2P) | 10232.5±0.6 |

| 23P1 | 0+(1++) | χb1(2P) | 10255.46±0.55 |

| 23P2 | 0+(2++) | χb2(2P) | 10268.65±0.55 |

| 33S1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(3S) | 10355.2±0.5 |

| 33PJ | 0+(J++) | χb(3P) | 10530±5 (stat.) ± 9 (syst.)[4] |

| 43S1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(4S) or Υ(10580) | 10579.4±1.2 |

| 53S1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(5S) or Υ(10860) | 10865±8 |

| 63S1 | 0−(1−−) | Υ(11020) | 11019±8 |

Notes:

- * Preliminary results. Confirmation needed.

The χb (3P) state was the first particle discovered in the Large Hadron Collider. The article about this discovery was first submitted to arXiv on 21 December 2011.[4][5] On April 2012, Tevatron's DØ experiment confirms the result in a paper published in Phys. Rev. D.[6][7]

QCD and quarkonia

The computation of the properties of mesons in Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is a fully non-perturbative one. As a result, the only general method available is a direct computation using lattice QCD (LQCD) techniques. However, other techniques are effective for heavy quarkonia as well.

The light quarks in a meson move at relativistic speeds, since the mass of the bound state is much larger than the mass of the quark. However, the speed of the charm and the bottom quarks in their respective quarkonia is sufficiently smaller, so that relativistic effects affect these states much less. It is estimated that the speed, v, is roughly 0.3 times the speed of light for charmonia and roughly 0.1 times the speed of light for bottomonia. The computation can then be approximated by an expansion in powers of v/c and v2/c2. This technique is called non-relativistic QCD (NRQCD).

NRQCD has also been quantized as a lattice gauge theory, which provides another technique for LQCD calculations to use. Good agreement with the bottomonium masses has been found, and this provides one of the best non-perturbative tests of LQCD. For charmonium masses the agreement is not as good, but the LQCD community is actively working on improving their techniques. Work is also being done on calculations of such properties as widths of quarkonia states and transition rates between the states.

An early, but still effective, technique uses models of the effective potential to calculate masses of quarkonia states. In this technique, one uses the fact that the motion of the quarks that comprise the quarkonium state is non-relativistic to assume that they move in a static potential, much like non-relativistic models of the hydrogen atom. One of the most popular potential models is the so-called Cornell potential

where is the effective radius of the quarkonium state, and are parameters. This potential has two parts. The first part, corresponds to the potential induced by one-gluon exchange between the quark and its anti-quark, and is known as the Coulombic part of the potential, since its form is identical to the well-known Coulombic potential induced by the electromagnetic force. The second part, , is known as the confinement part of the potential, and parameterizes the poorly understood non-perturbative effects of QCD. Generally, when using this approach, a convenient form for the wave function of the quarks is taken, and then and are determined by fitting the results of the calculations to the masses of well-measured quarkonium states. Relativistic and other effects can be incorporated into this approach by adding extra terms to the potential, much in the same way that they are for the hydrogen atom in non-relativistic quantum mechanics. This form has been derived from QCD up to by Y. Sumino in 2003.[9] It is popular because it allows for accurate predictions of quarkonia parameters without a lengthy lattice computation, and provides a separation between the short-distance Coulombic effects and the long-distance confinement effects that can be useful in understanding the quark/anti-quark force generated by QCD.

Quarkonia have been suggested as a diagnostic tool of the formation of the quark–gluon plasma: both disappearance and enhancement of their formation depending on the yield of heavy quarks in plasma can occur.

See also

- Onium

- OZI Rule

- J/ψ meson

- Phi meson

- Upsilon meson

- Theta meson

- Non-relativistic QCD

- Lattice QCD

- Quantum chromodynamics

References

- ^

LHCb collaboration; Aaij, R.; Abellan Beteta, C.; Adeva, B.; Adinolfi, M.; Adrover, C.; Affolder, A.; Ajaltouni, Z.; Albrecht, J. (February 2013). "Determination of the X(3872) meson quantum numbers". Physical Review Letters. 1302 (22): 6269. arXiv:1302.6269. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.110v2001A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.222001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ "A new particle discovered by BaBar experiment". Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare. 6 July 2005. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ B. Aubert et al. (BaBar Collaboration) (2005). "Observation of a broad structure in the π+π−J/ψ mass spectrum around 4.26 GeV/c2". Physical Review Letters. 95 (14): 142001. arXiv:hep-ex/0506081. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95n2001A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.142001.

- ^ a b

ATLAS Collaboration (2012). "Observation of a new

χ

b state in radiative transitions to

ϒ

(1S) and

ϒ

(2S) at ATLAS". arXiv:1112.5154v4 [hep-ex]. - ^ Jonathan Amos (2011-12-22). "LHC reports discovery of its first new particle". BBC.

- ^ Tevatron experiment confirms LHC discovery of Chi-b (P3) particle

- ^ Observation of a narrow mass state decaying into Υ(1S) + γ in pp collisions at 1.96 TeV

- ^ Hee Sok Chung; Jungil Lee; Daekyoung Kang (2008). "Cornell Potential Parameters for S-wave Heavy Quarkonia". Journal of the Korean Physical Society. 52 (4): 1151. arXiv:0803.3116. Bibcode:2008JKPS...52.1151C. doi:10.3938/jkps.52.1151.

- ^ Y. Sumino (2003). "QCD potential as a "Coulomb-plus-linear" potential". Phys. Lett. B. 571: 173–183. arXiv:hep-ph/0303120. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2003.05.010.