Quick & Flupke

| Quick and Flupke | |

|---|---|

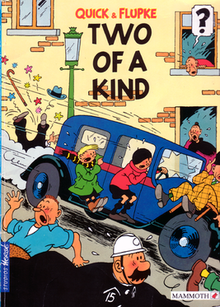

Quick & Flupke - Two of a Kind (English version) | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Casterman |

| Publication date | 1930-1940 |

| Main character(s) | Quick Flupke No. 15 |

| Creative team | |

| Written by | Hergé |

| Artist(s) | Hergé |

The exploits of Quick and Flupke (Template:Lang-fr) is a comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. Serialised weekly from January 1930 to 1940 in [Le Petit Vingtième] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), the children's supplement of conservative Belgian newspaper [Le Vingtième Siècle] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("The Twentieth Century"), the series ran alongside Hergé's better known The Adventures of Tintin.

It revolves around the lives of two misbehaving boys, Quick and Flupke, who live in Brussels, and the conflict that they get into with a local policeman.

In 1983, the series provided the basis for an animated television adaptation.

History

Background

Abbé Norbert Wallez appointed Hergé editor of a children's supplement for the Thursday issues of [Le Vingtième Siècle] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), titled [Le Petit Vingtième] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("The Little Twentieth").[1] Carrying strong Catholic and fascist messages, many of its passages were explicitly anti-semitic.[2] For this new venture, Hergé illustrated L'Extraordinaire Aventure de Flup, Nénesse, Poussette et Cochonnet (The Extraordinary Adventure of Flup, Nénesse, Poussette and Cochonnet), a comic strip authored by one of the paper's sport columnists, which told the story of two boys, one of their little sisters, and her inflatable rubber pig.[3] Hergé was unsatisfied, and eager to write and draw a comic strip of his own. He was fascinated by new techniques in the medium – such as the systematic use of speech bubbles – found in such American comics as George McManus' Bringing up Father, George Herriman's Krazy Kat and Rudolph Dirks's Katzenjammer Kids, copies of which had been sent to him from Mexico by the paper's reporter Léon Degrelle, stationed there to report on the Cristero War.[4]

Hergé developed a character named Tintin as a Belgian boy reporter who could travel the world with his fox terrier, Snowy – "Milou" in the original French – basing him in large part on his earlier character of Totor and also on his own brother, Paul.[5] Although Hergé wanted to send his character to the United States, Wallez instead ordered him to set his adventure in the Soviet Union, acting as a work of anti-socialist propaganda for children. The result, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, began serialisation in Le Petit Vingtième on 10 January 1929, and ran until 8 May 1930.[6] Popular in Francophone Belgium, Wallez organized a publicity stunt at the Gare de Nord station, following which he organized the publication of the story in book form.[7] The popularity of the story led to an increase in sales, and so Wallez granted Hergé two assistants, Eugène Van Nyverseel and Paul "Jam" Jamin.[8][9]

Publication

According to one of Hergé's later recollections, he had returned to work following a holiday to find that the staff had publicly announced that he would be producing a new series, as a joke on his expense. Obliged to the commitment, he had to develop a new strip with only a few days notice.[10] In devising a scenario, he was influenced by the French film Les Deux gosses ("The two kids"), released the previous year, as well as by his own childhood in Brussels.[10] Other cinematic influences included the films of Charlie Chaplin, upon whom the policemen are based.[11]

The strip first appeared in [Le Petit Vingtième] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) on 23 January 1930, at the time starring Quick without Flupke.[10] Quick appeared on the cover of that issue, stating "Hello, friends. Don't you know me? I'm Quick, a kid from Brussels, and beginning today I'll be here every Thursday to tell you what happened to me during the week."[10] Hergé borrowed the name "Quipke" from one of his friends.[12] Three weeks later he added the second boy as a sidekick, naming him "Suske".[10] He would soon be renamed "Flupke" ("Little Philip" in Flemish).[12] Quick et Flupke would be published in [Le Petit Vingtième] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) every Thursday for the next six years.[12] Hergé devoted little time to the series, typically only starting work on each strip on the morning of the day that the page were being typset, proceeding to rush to finish them within one or two hours.[11] Jamin thought that Hergé had greater difficulty with Quick and Flupke than with The Adventures of Tintin, because of the need for a completely new idea each week.[10]

Hergé used the strip as a vehicle for jokes not considered appropriate for The Adventures of Tintin.[10] In particular he made repeated allusions to the fact that the strip was a cartoon; in one example, Flupke walks onto the ceiling, flies around, and then throws Quick's detached head into the air, before waking up to proclaim "Thank goodness it wasn't real! Hergé isn't still making us act like cartoons!"[13] Hergé inserted himself into the strip on numerous occasions; in "The Kidnapping of Hergé", Quick and Flupke kidnap Hergé from his office, and force him to sign a statement proclaiming "I, the undersigned, Hergé, declare that, contrary to how I make it seem every week, the parties of Quick and Flupke are good, smart, obedient, etc., etc."[13]

Throughout the series, Hergé would give characters names that illustrated a play on words, such as the veterinarian M. Moraurat (mort aux rats, "death to rats"), and the two boxers Sam Suffy (ça suffit, "I've had enough") and Mac Aronni ("macaroni").[11] He also included references to present events, in one instance lampooning Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.[14] In another, the boys listen to a radio program filled with nationalistic proclamations from Hitler, Mussolini, Neville Chamberlain, Édouard Herriot, a Bolshevik, and a Japanese, after which they run away to listen to an organ grinder.[15]

In late 1935, the editors of Cœurs Vaillants ("Valiant Hearts"), a Catholic newspaper who published The Adventures of Tintin in France, requested that Hergé create a series about protagonists with a family. Hergé agreed, creating the Jo, Zette and Jocko series, but soon found himself overworked in writing and drawing three comics at once. Quick & Flupke were subsequently put on the back burner.[16]

For New Year 1938, Hergé designed a special cover for Le Petit Vingtième in which the characters of Quick & Flupke were featured alongside those from The Adventures of Tintin and Jo, Zette and Jocko.[17] Hergé eventually abandoned the series in order to spend more time on The Adventures of Tintin, his more famous comic series.

Colouration and re-publication

After Hergé's death, the books were coloured by the Studios Hergé and re-issued by the publishing house Casterman in 12 volumes, between 1985 and 1991.

Critical analysis

Hergé biographer Pierre Assouline asserted that the strip was "completely opposite in spirit" to Hergé's preceding Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, due to the fact that it was "utterly lacking in ambiguity or cynicism."[12] He thought it unfair that they had been eclipsed by the fame of The Adventures of Tintin, because they have a "lightness of touch, a charm, a tenderness and poetry" that are absent from the rest of Hergé's work.[11] Considering them to be an updated version of the German author Wilhelm Busch's characters Max and Moritz.[11]

Another of Hergé's biographers, Benoît Peeters, thought that Quick and Flupke worked as a "perfect counterpoint" to The Adventures of Tintin, contrasting two-strip jokes with long stories, familiarity with exoticism, and the boys' fight against order with Tintin's fight to impose it.[10] He also thought it noteworthy that in the series, family bonds are "reduced to their simplest expression", with parental figures rarely appearing and the protagonists this growing up "more or less alone, protecting them as best they can against a monotonous adult world".[18] Tintinologist Phillipe Goddin believed that the series expressed Hergé's "affection for his Brussels roots."[19]

List of volumes

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (April 2010) |

Unlike Hergé's other series there is no real chronological order to the books, though often the order that they were published in is used.

High Tension

Initially published in September 1985 as Haute Tension. Haute Tension is not by Hergé, but by Johan de Moor, the son of Hergé's assistant Bob de Moor.

Double Trouble

Initially called Jeux interdits and first published in September 1985. The gags included in this volume are:

Tournament, Flying, Happy Easter, Dangerous Dog, The Swing, Everyone Gets a Turn, Magic, Drama, Posting of Notices Prohibited, Officer No. 15 Pulls a Prank, Directions, Traffic, Haute Couture, Unbreakable, Bravery, Oil-Based Paint, Forbidden Games, William Tell, Same Reasons, Dodging the Fare, The Soapbox, Caution, and Quick the Electrician.

Two of a Kind

Initially published as Tout va bien in September 1985. The gags included in this volume are:

Manners, How to Build a Glider, Happy Christmas, Mad Dog, A Present for Aunt Mary, Handyman, What Weather!, Having the Last Word, Three of a Kind, Heart of Gold, Rope Trick, Lucky Strike, All or Nothing, Honesty, Hot Stuff, Horror Story, Quick at the Wheel, Acrobatics, Right as Rain, Natural Disaster, Big Mouth, Musical Ear, and A Helping Hand.

Full Sail

Initially published as Toutes voiles dehors in 1986. The gags included in this volume are:

Naval Program, An Eye for an Eye, The Dog That Came Back, Locution, Back to School, Problem, Dowsing, Happy Easter!, Happy New Year!, A Picturesque Spot, Knowing How to Light a Fire, Demonstrative, A Good Picture, Lost in the Night, A Record, Penalty, Barely Believable, The Follies, Demand, The Tunnel, Winter Sports, New Year, and Peaceful Idleness.

It's Your Turn

Initially published as Chacun son tour in 1986. The gags included in this volume are:

Who Wants This Glove?, At the Optician’s, Lullaby, Evangelical Love, The Dangers of Tobacco, The Little Genius, Angling, Sleeplessness, Make a Wish, Pointless Search, Music to Calm the Nerves, The Trials and Tribulations of Officer 15 (2), Speeding Police, Flupke the Goalkeeper, Crosswords, Broadcasting, The Rara Avis, The Rescuers, Flupke on Display, Camp at Night, Acrobatics, Foolish Games, and Vernal Poem.

Without Mercy

Initially Pas de quartier January 1987. The gags included in this volume are:

A Bit of History, Quick Out West, Be Kind to Animals, Swimming, Quick the Golf Pro, Horseriding, Windstorm, A Nice Surprise, Sports, Essay, Skating, Light Headed, Cleaning Day, Circus Games, A Nice “Shot”, Rescue, Automatic Door Closer, A Good Line of Work, A Beautiful-Target, Payback, Camping (1), (2), and (3).

Excuse Me Ma'am

Initially published as Pardon Madame in January 1987. The gags included in this volume are:

If I Had a Million, Sad Story, Winning Ticket, The Road of Virtue, The Continuing Business, Hunting Story, The Child Prodigy, Nature’s Response…, Everything’s Fine, Reform, Gratitude, It’s Your Turn, Vendetta, Faith in Publicity, Afraid of Germs, Thunderstorm, Simple Question, Eternal Youth, A Great Traveler, Caution, Bad Encounter, Meteorology, The Great Resource, and The Punished Artist.

Long Live Progress

Published as Vive le progrès in September 1987. The gags included in this volume are:

Back to School, Valve Painting, Ostrich Eggs, Return to the Soil, Higher Education, The Mosquito, Serious Customers, Obsession, Among Artists, Deafness, Happy Easter, Surplus Value, Natural Bronzing, Swaps, Long Live Vacations, Clarification, Progress, Traffic, Break-in, The Example, About-Face, No Deal, and Resolution.

Catastrophe

Catastrophe [January 1988] The gags included in this volume are:

Vocation, No! Carnival is Not Dead!, There’s a Butterfly, and Then There’s a Butterfly, The Alarm, The World As Flupke Would Like It (1), (2), & (3), The Remedy, Interview, He Wanted a Disaster, Mix Up, Upper-Style Horsemanship, An Inner Man, Apropos, The Art of Diving, Spiritualism, The Etruscan Vase, Secret Police, The Hiccup, Quick Builds a Wireless System, Pilfering, The Pancakes, and Patient Flupke.

Pranks and Jokes

Farces et attrapes [January 1989] The gags included in this volume are:

Gardening, Sharpshooter, Heat, A Breakdown, Quick the Mechanic, Quick the Cabinetmaker, Well-Endorsed, House Chores, Simple Loan, Ball, Flytrap, Trapeze, Flupke the Model Maker, Constructions, A Masterstroke, Barely Believable, You Can’t Judge a Book by Its Cover, The Rocket, The Scrupulous Artist, The Prey, For Christmas, Temptation, and Beekeeping.

Bluffmasters

Coups de bluff January 1990. The gags included in this volume are:

Boating, Technicality, Intuition, The Cat and the Mouse, Quick’s Toothache, Championship, Time is Money, Pedestrian Crossing, Cruelty, At Last the Sun, Bluff, Pastoral, Superstition, Perfumery, Be Kind to Animals!, Cold Shower, The Look-Alike, Tire Story, Suspicions, Harassments, World Record, Stability, Logic, and Experience.

Fasten Your Seat Belts

Attachez vos ceintures January 1991. The gags included in this volume are:

Real Cleaning, A Poor Woman, Seascape, Quick Learns Boxing, Music to Calm the Nerves, Pacifism, The Unbeatable, Advertisement, Method of Work, Quick the Clockmaker, Soccer, At the Auto Show, Crazy Story, A Serious Affair, Argumentativeness, Music-Mad Quick, So Do It, Innocence, Children’s Rights, The Recipe, Yo-Yo, Metamorphoses, and Legless Cripple Story.

Cameos in The Adventures of Tintin

Quick & Flupke made short appearances in The Adventures of Tintin books:

- They are among the crowd seeing Tintin off in the first panel of Tintin in the Congo, in both the 1931 and 1946 editions.

- In The Shooting Star, Quick and Flupke can be seen running towards the docks as the expedition is about to set off.

- The Seven Crystal Balls features a pair of boys who play a trick on Captain Haddock. They are made to look very similar to Quick and Flupke though the resemblance is minor given that the event takes place in La Rochelle in France and not an inland city in Belgium.

- Quick & Flupke also appear on the back cover of some book editions of the Adventures of Tintin: they are about to fire a slingshot at Captain Haddock and/or his bottle of whisky.

English translations

The English version of Quick & Flupke was produced in the early-1990s, and consisted of only two books, published by Mammoth Publishing. The books were translated by Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner, who had previously translated The Adventures of Tintin. The text in the English volumes is not lettered in the same way as other Hergé books in English. The two English volumes are direct translations of strips in the French volumes Jeux Interdits and Tout va Bien. The English edition comics are all coloured, and named Double Trouble and Two of a Kind. Under Full Sail and Fasten Your Seatbelts were also published by Egmont.

In January 2008 Euro Books India (a subsidiary of Egmont) released English translations of all the 11 titles that were originally written by Hergé. Interestingly, the first two books were given different titles in the India release by Euro Books: Double Trouble was called Forbidden Games and Two of a Kind was renamed Everything's Fine.

Egmont planned to gradually release the English translations in the UK. Two of them (#4, Under Full Sail and #12, Fasten Your seat Belts), translated by David Radzinowicz, were released in 2009. As of late 2011, no more had been released.

Television series

In the 1980s the books were made into a television series, the creation of which was supervised by Studios Hergé. It was recently re-issued on Multi-regional DVD in France under 3 titles - 'Coups de Bluff, Tout va Bien and Jeux Interdits.

References

Footnotes

- ^ Thompson 1991, pp. 24–25; Peeters 1989, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 38.

- ^ Peeters 2012, p. 32; Assouline 2009, p. 16; Farr 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 17; Farr 2001, p. 18; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Farr 2001, p. 12; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002; Peeters 2012, p. 34; Thompson 1991, p. 25; Assouline 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Peeters 2012, pp. 34–37; Assouline 2009, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Peeters 2012, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Assouline 2009, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Peeters 2012, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Peeters 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Assouline 2009, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Assouline 2009, p. 23.

- ^ a b Peeters 2012, p. 45.

- ^ Goddin 2008, p. 148. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGoddin2008 (help)

- ^ Assouline 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Peeters 2012, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Goddin 2008, p. 19. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGoddin2008 (help)

- ^ Peeters 2012, p. 88.

- ^ Goddin 2008, p. 70. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGoddin2008 (help)

Bibliography

- Assouline, Pierre (2009) [1996]. Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Charles Ruas (translator). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goddin, Philippe (2008). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume I, 1907–1937. Michael Farr (translator). San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-706-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goddin, Philippe (2008). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume I, 1907–1937. San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-706-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Wikipedia articles that are excessively detailed from April 2010

- Belgian comic strips

- Comics by Hergé

- Comic strip duos

- Fictional Belgian people

- Fictional tricksters

- Gag-a-day comics

- 1930 comics debuts

- 1940 comics endings

- Child characters in comics

- Brussels in fiction

- Comics set in the 1930s

- Belgian comics characters

- Comics characters introduced in 1930

- Comics adapted into animated series

- Comics adapted into television series

- Art Deco