Requiem for a Dream

| Requiem for a Dream | |

|---|---|

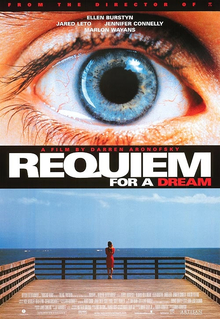

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Darren Aronofsky |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Matthew Libatique |

| Edited by | Jay Rabinowitz |

| Music by | Clint Mansell |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Artisan Entertainment |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 101 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4.5 million |

| Box office | $7.4 million[2] |

Requiem for a Dream is a 2000 American psychological tragedy film[3][4][5] directed by Darren Aronofsky and starring Ellen Burstyn, Jared Leto, Jennifer Connelly, and Marlon Wayans.[6] The film is based on the novel of the same name by Hubert Selby Jr., with whom Aronofsky wrote the screenplay.

The film depicts four characters affected by drug addiction. Their addictions cause them to become imprisoned in a world of delusion and reckless desperation. Once that delusional state is overtaken by reality, by the end of the film, they are left as hollow shells of their former selves.[7] The film depicts how drug abuse can alter a person's physical and psychological state and mindset.

Requiem for a Dream was screened out of competition at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival[8] and received positive reviews from critics upon its U.S. release. Burstyn was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance. The music for the movie was written by composer Clint Mansell.

Plot

Sara Goldfarb (Burstyn), a widow who lives alone in a Brighton Beach apartment, spends her time watching infomercials. Her son Harry (Leto) is a heroin addict, along with his friend Tyrone (Wayans) and girlfriend Marion (Connelly). The three traffic heroin in a bid to realize their dreams; Harry and Marion plan to open a clothing store for Marion's designs, while Tyrone seeks escape from the ghetto and the approval of his mother. When Sara receives a call that she has been invited to her favorite game show, she begins a restrictive crash diet in an attempt to fit into a red dress that she wore at Harry's graduation. At the recommendation of a friend, she visits an unscrupulous physician who prescribes her a regimen of amphetamines to control her appetite. She begins losing weight rapidly and is excited by how much energy she has. When Harry recognizes the signs and implores her to get off the amphetamines, Sara insists that the chance to appear on television and the increased admiration from her friends are her remaining reasons to live. Sara becomes frantic waiting for the invitation and increases her dosage, which causes her to develop amphetamine psychosis.

Tyrone is caught in a shootout between black traffickers and the Sicilian Mafia, and is arrested in spite of his innocence. Harry has to use most of their earned money to post bail. The local supply of heroin becomes restricted, and they are unable to find any for either use or sale. Eventually, Tyrone hears of a large shipment coming to New York from Florida, but the price is doubled and the minimum high. Harry desperately encourages Marion to prostitute herself to her psychiatrist Arnold for the money. This request, along with their mounting withdrawal, strains their relationship. Sara's increased amphetamine intake distorts her sense of reality and comes to a head in the form of an elaborate and horrific hallucination in which she is mocked by a crowd from the television show and attacked by her refrigerator. Sara flees her apartment for the office of the casting agency in Manhattan to confirm when she will be on television. Sara's clearly disturbed state brings about her involuntary commitment to a psychiatric ward, where – after failing to respond to medication – she undergoes electroconvulsive therapy. Harry and Tyrone travel to Miami to buy directly from the wholesaler. However, they are forced to stop at a hospital because of the deteriorating condition of Harry's increasingly gangrenous arm. The shocked doctor identifies Harry and Tyrone's situation as that of addicts and has them arrested.

Back in New York, a desperate Marion sells her body to the pimp Big Tim in exchange for heroin, and receives an even bigger score when she subjects herself to a humiliating sex show at his behest. Sara's treatment leaves her in a dissociated and vegetative state, much to the horror of her visiting friends. Harry's infected arm is amputated and he is emotionally distraught by the knowledge that Marion will not visit him. Marion returns home from the show and lies on her sofa, clutching her score of heroin and surrounded by her crumpled and discarded clothing designs. Tyrone is hostilely taunted by racist prison guards while enduring a combination of manual labor and withdrawal symptoms. Each of the four characters curl miserably into a fetal position. Sara imagines herself as the beautiful winner of the game show, with Harry – married and successful – arriving as a guest. The film ends with this dream as Sara and Harry lovingly embrace.

Cast

- Ellen Burstyn as Sara Goldfarb

- Jared Leto as Harry Goldfarb

- Jennifer Connelly as Marion Silver

- Marlon Wayans as Tyrone C. Love

- Christopher McDonald as Tappy Tibbons

- Mark Margolis as Mr. Rabinowitz

- Louise Lasser as Ada

- Marcia Jean Kurtz as Rae

- Sean Gullette as Arnold, Marion's psychiatrist

- Keith David as Big Tim, Marion's pimp

- Dylan Baker as Southern Doctor

- Ajay Naidu as Mailman

- Ben Shenkman as Dr. Spencer

- Hubert Selby, Jr. as Laughing guard

- Darren Aronofsky (uncredited) as Visitor

Production

The film rights to Hubert Selby Jr.'s book were optioned by Scott Vogel for Truth and Soul Pictures in 1997 prior to the release of Aronofsky's film π.

The bathtub scene in the film was inspired by Satoshi Kon's 1997 anime film Perfect Blue.[9]

Themes

The majority of reviewers characterized Requiem for a Dream in the genre of "drug movies", along with films like The Basketball Diaries, Trainspotting, Spun, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.[10][11] However, Aronofsky has said:

Requiem for a Dream is not about heroin or about drugs... The Harry-Tyrone-Marion story is a very traditional heroin story. But putting it side by side with the Sara story, we suddenly say, 'Oh, my God, what is a drug?' The idea that the same inner monologue goes through a person's head when they're trying to quit drugs, as with cigarettes, as when they're trying to not eat food so they can lose 20 pounds, was really fascinating to me. I thought it was an idea that we hadn't seen on film and I wanted to bring it up on the screen.[12]

Style

As in his previous film, π, Aronofsky uses montages of extremely short shots throughout the film (sometimes termed a hip hop montage).[10] While an average 100-minute film has 600 to 700 cuts, Requiem features more than 2,000. Split-screen is used extensively, along with extremely tight closeups.[10][13] Long tracking shots (including those shot with an apparatus strapping a camera to an actor, called the Snorricam) and time-lapse photography are also prominent stylistic devices.[14]

To portray the shift from the objective, community-based narrative to the subjective, isolated state of the characters' perspectives, Aronofsky alternates between extreme closeups and extreme distance from the action and intercuts reality with a character's fantasy.[13] Aronofsky aims to subjectivize emotion, and the effect of his stylistic choices is personalization rather than alienation.[14] The camera serves as a vehicle for exploring the characters' states of mind, hallucinations, visual distortions, and corrupted sense of time.[15]

The film's distancing itself from empathy is structurally advanced by the use of intertitles (Summer, Fall, Winter), marking the temporal progress of addiction.[14] The average scene length shortens as the film progresses (beginning around 90 seconds to two minutes) until the movie's climactic scenes, which are cut together very rapidly (many changes per second) and are accompanied by a score which increases in intensity accordingly. After the climax, there is a short period of serenity, during which idyllic dreams of what might have been are juxtaposed with portraits of the four shattered lives.[13]

Release

Requiem for a Dream premiered at the 2000 Cannes Film Festival on May 14, 2000, and the 2000 Toronto International Film Festival on September 13 before a wide release on October 27.

Rating

In the United States, the film was originally rated NC-17 by the MPAA, but Aronofsky appealed the rating, claiming that cutting any portion of the film would dilute its message. The appeal was denied and Artisan decided to release the film unrated.[16] An R-rated version was released on video, with the sex scene edited, but the rest of the film identical to the unrated version.

Critical reception

Requiem for a Dream received positive reviews from critics and has an approval rating of 79% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 136 reviews, with an average rating of 7.4/10. The critical consensus states, "Though the movie may be too intense for some to stomach, the wonderful performances and the bleak imagery are hard to forget."[17] The film also has a score of 68 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 32 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews."[18] Film critic James Berardinelli considered Requiem for a Dream the second best film of the decade, behind The Lord of the Rings film trilogy.[19] Roger Ebert gave the film 3½ stars out of four, stating that "What is fascinating about Requiem for a Dream,...is how well [Aronofsky] portrays the mental states of his addicts. When they use, a window opens briefly into a world where everything is right. Then it slides shut, and life reduces itself to a search for the money and drugs to open it again."[20] Elvis Mitchell, writing for The New York Times, gave the film a positive review, stating that "After the young director's phenomenal debut with the barely budgeted Pi, which was like watching a middleweight boxer win a fight purely on reflexes, he comes back with a picture that shows maturation."[21]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian, lauded the film as an "agonising and unflinchingly grim portrait of drug abuse" and "a formally pleasing piece of work – if pleasing can possibly be the right word."[22] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone wrote that "no one interested in the power and magic of movies should miss it."[23] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly, who gave the work an "A" grade, argued that it "may be the first movie to fully capture the way drugs dislocate us from ourselves" and said, "The movie, a full-throttle mind-bender, is hypnotically harrowing and intense, a visual and spiritual plunge into the seduction and terror of drug addiction."[24] Scott Brake of IGN gave the film a 9.0 out of 10 and argued, "The reason it works so well as a film about addiction is that, in every frame, the film itself is addictive. It's absolutely relentless, from Aronofsky's bravura cinematic techniques (split screens, complex cross-cutting schemes, hallucinatory visuals) to Clint Mansell's driving, hypnotic score (performed by the Kronos Quartet), the movie compels you to watch it."[25]

Some critics were less positive, however. On Mr. Showbiz, Kevin Maynard stated that the film is "never the heart-wrenching emotional experience it seems intended to be." J. Rentilly billed the work as "chilling and technically proficient and, also, fairly hollow." Desson Thompson of The Washington Post argued that its characters are "mostly relegated to human mannequins in Aronofsky's visual schemes". David Sterritt of the Christian Science Monitor wrote that "Aronofsky's filmmaking gets addicted to its own flashy cynicism".[26]

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award ceremony | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001[27] | Academy Awards | Best Actress | Ellen Burstyn | Nominated[28] |

Ellen Burstyn was nominated for several other awards including the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role, losing to Julia Roberts in both instances.

In 2007, Requiem for a Dream was picked as one of the 400 nominated films for the American Film Institute list AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition).[29] In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed Requiem for a Dream as the 29th best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its members.[30] In a 2016 international critics' poll conducted by BBC, the film, Toni Erdmann and Carlos were tied together and were three voted together as the 100 greatest motion pictures since 2000.[31]

Requiem for a Dream was listed as the 40th best-edited film of all time in a 2012 survey of members of the Motion Picture Editors Guild.[32]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack was composed by Clint Mansell with the string ensemble performed by Kronos Quartet. The string quartet arrangements were written by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang.

The soundtrack was re-released with the album Requiem for a Dream: Remixed, which contains remixes of the music by Paul Oakenfold, Josh Wink, Jagz Kooner, and Delerium, among others.

"Lux Aeterna" is an orchestral composition by Mansell, the leitmotif of Requiem for a Dream, and the penultimate piece in the film's soundtrack. The popularity of this piece led to its use in popular culture outside the film, in film and teaser trailers,[33] and with multiple remixes and remakes by other producers.[34]

See also

References

- ^ "REQUIEM FOR A DREAM (18)". British Board of Film Classification. November 23, 2000. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "Requiem for a Dream (2000)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. January 1, 2002. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ "The Needle and the Damage Done: Requiem for a Dream". www.papermag.com. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

I wanted to make a tragedy, in the classical sense, says Aranofsky.

- ^ Leigh, Danny. "Arts: Requiem for a Dream". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

Eighty percent of ticket sales across the world go to Hollywood movies, he points out, and because of that, people are almost brainwashed into expecting a catharsis. But anyone who's been on the planet long enough knows that, in the end, things seldom work out OK. That's what tragedy is about. And tragedy is an art form that's been killed by Hollywood. I mean, with Requiem, the catharsis is really there for the audience the day after they've seen the movie.

- ^ Jagernauth, Kevin. "Watch: Darren Aronofsky Talks Myth, Storytelling And The Value Of Tragedy In 7-Minute Video". www.indiewire.com. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Leigh, Danny. "Arts: Requiem for a Dream". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 3, 2000). "Requiem for a Dream". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Requiem for a Dream". Festival-Cannes.com. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ "The cult Japanese filmmaker that inspired Darren Aronofsky". Dazed. August 27, 2015.

- ^ a b c Booker, M. (2007). Postmodern Hollywood. New York: Praeger Publishing. ISBN 0-275-99900-9.

- ^ Boyd, Susan (2008). Hooked. New York: Routledge. pp. 97–98. ISBN 0-415-95706-0.

- ^ Stark, Jeff (October 13, 2000). ""It's a punk movie"". Salon. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c Dancyger, Ken (2002). The Technique of Film and Video Editing. London: Focal Press. pp. 257–258. ISBN 0-240-80420-1.

- ^ a b c Powell, Anna (2007). Deleuze, Altered States and Film. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-7486-3282-4.

- ^ Skorin-Kapov, Jadranka (2015) Darren Aronofsky's Films and the Fragility of Hope, p.32 Bloomsbury Academic

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene; Anthony Kaufman (August 25, 2000). "MPAA Upholds NC-17 Rating for Aronofsky's "Requiem for a Dream"; Artisan Stands Behind Film and Will Release Film Unrated". indieWIRE. SnagFilms. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ "Requiem for a Dream Movie Reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ "Requiem for a Dream Reviews". Metacritic. n.d. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Top 10 Movies of the Decade". ReelViews.com. Retrieved March 1, 2011

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 3, 2000). "Requiem for a Dream". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (October 6, 2000). "Movie Review: Requiem for a Dream". The New York Times. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (January 18, 2001). "Living in Oblivion". The Guardian. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 11, 2000). "Requiem for a Dream". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (October 13, 2000). "Movie Review: 'Requiem for a Dream' Review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ "Review of Requiem for a Dream". IGN. October 20, 2000. Retrieved December 13, 2004.

- ^ "Critic Reviews for Requiem for a Dream". Metacritic. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Lyman, Rick (March 4, 2001). "OSCAR FILMS/ACTORS: An Angry Man and an Underused Woman; Ellen Burstyn Enjoys Her Second Act". The New York Times.

- ^ "Award Nominees – 2000". The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) Ballot

- ^ "The 75 Best Edited Films". Editors Guild Magazine. 1 (3). May 2012.

- ^ "The 21st century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "The 75 Best Edited Films". Editors Guild Magazine. 1 (3). May 2012. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015.

- ^ Smith, C. Molly. "The ubiquitous 'Requiem for a Dream' score is 15 years old". EW.com. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 17, 2002). "The Movie Answer Man". Retrieved January 8, 2014.

External links

- 2000 films

- 2000s independent films

- 2000s psychological drama films

- American independent films

- American films

- American psychological drama films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Darren Aronofsky

- Films about heroin addiction

- Films about the illegal drug trade

- Films about drugs

- Films about prostitution in the United States

- Films based on American novels

- Films set in Brooklyn

- Films shot in New York City

- Artisan Entertainment films

- Films with screenplays by Darren Aronofsky

- Films scored by Clint Mansell

- Films set in psychiatric hospitals

- Films about television

- Protozoa Pictures films