Effects of meditation

Research on the processes and effects of meditation is a growing subfield of neurological research.[1][2][3][4][5][6] Modern scientific techniques and instruments, such as fMRI and EEG, have been used to see what happens in the body of people when they meditate, and how their bodies and brain change after meditating regularly.[2][7][8][9][10]

These studies have shown substantial bodily changes as a consequence of regular meditative practice. For instance, one study by Richard Davidson and Jon Kabat-Zinn showed that eight weeks of mindfulness-based meditation produced significant increases in left-sided anterior brain activity, which is associated with positive emotional states.[11] Positive emotion may be a skill which can be achieved with training similar to learning to ride a bike or play the piano.[12]

Since the 1950s hundreds of studies on meditation have been conducted, though many of the early studies were flawed and thus yielded unreliable results.[13][14] More recent reviews have pointed out many of these flaws with the hope of guiding current research into a more fruitful path.[15] More reports assessed that further research needs to be directed towards the theoretical grounding and definition of meditation.[13][16]

Meditation has been practiced within religious traditions since ancient times, especially within monastic centers. These days there also exist many secular programs in the West including mindfulness-based programs.[17] Today mindfulness-based meditative practices have become popular within the Western medical and psychological community, due mainly to the observable, positive impact such processes have on patients suffering from stress-related health conditions.[11]

Meditation within Western psychology

The relaxation response

Dr. Herbert Benson, founder of the Mind-Body Medical Institute, which is affiliated with Harvard University and several Boston hospitals, reports that meditation induces a host of biochemical and physical changes in the body collectively referred to as the "relaxation response".[18] The relaxation response includes changes in metabolism, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure and brain chemistry. Benson and his team have also done clinical studies at Buddhist monasteries in the Himalayan Mountains.[19] Benson wrote The Relaxation Response to document the benefits of meditation, which in 1975 were not yet widely known.[20]

Calming effects of meditation

According to a March 2006 article in the "Psychological Bulletin", EEG activity begins to slow as a result of the practice of meditation.[21] The human nervous system is composed of a parasympathetic system, which works to regulate heart rate, breathing and other involuntary motor functions, and a sympathetic system, which arouses the body, preparing it for vigorous activity. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has written, "It is thought that some types of meditation might work by reducing activity in the sympathetic nervous system and increasing activity in the parasympathetic nervous system," or equivalently, that meditation produces a reduction in arousal and increase in relaxation.

Western therapeutic use and MBSR

Meditation has entered the mainstream of health care as a method of stress and pain reduction. As a method of stress reduction, meditation has been used in hospitals in cases of chronic or terminal illness to reduce complications associated with increased stress that include depressed immune systems. There is growing agreement in the medical community that mental factors such as stress significantly contribute to a lack of physical health, and there is a growing movement in mainstream science to fund research in this area. There are now several mainstream health care programs which aid those, both sick and healthy, in promoting their inner well-being, especially mindfulness-based programs such as Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

A 2003 meta-analysis found that mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), which involves continuous awareness of consciousness, without seeking to censor thoughts, concluded that the form of meditation may be broadly useful for individuals attempting to cope with clinical and nonclinical problems. Diagnoses for which MBSR was found to be helpful included chronic pain, fibromyalgia, cancer patients and coronary artery disease. Improvements were noted for both physical and mental health measures.[22]

Flow

Mindfulness meditation, anapanasati, and related techniques, are intended to train attention for the sake of provoking insight. A wider, more flexible attention span makes it easier to be aware of a situation, easier to be objective in emotionally or morally difficult situations, and easier to achieve a state of responsive, creative awareness or "flow".[23] Research from Harvard medical school also shows that during meditation, physiological signals show that there is a decrease in respiration and increase in heart rate and blood oxygen saturation levels.[24]

Research by style of meditation

Insight meditation

A study done by Yale, Harvard, Massachusetts General Hospital have shown that meditation increases gray matter in specific regions of the brain and may slow the deterioration of the brain as a part of the natural aging process.

The experiment included 20 individuals with intensive Buddhist "insight meditation" training and 15 who did not meditate. The brain scan revealed that those who meditated have an increased thickness of gray matter in parts of the brain that are responsible for attention and processing sensory input. Some of the participants meditated for 40 minutes a day while others had been doing it for years. The results showed that the change in brain thickness depended upon the amount of time spent in meditation. The increase in thickness ranged between .004 and .008 inches (0.1016mm – 0.2032mm).[25][26]

Kundalini yoga meditation

There have been some preliminary studies done on some of the many types of meditation found within the branch of Yoga known as Kundalini. One study showed the cooling of meditators hands as they practiced Sahaja Yoga meditation and another study showed some relaxation while meditators paid attention to their breathing.

A study comparing practitioners of Sahaja Yoga meditation with a group of non meditators doing a simple relaxation exercise, measured a drop in skin temperature in the meditators compared to a rise in skin temperature in the non meditators as they relaxed. The researchers noted that all other meditation studies that have observed skin temperature have recorded increases and none have recorded a decrease in skin temperature. This suggests that Sahaja Yoga meditation, being a mental silence approach, may differ both experientially and physiologically from simple relaxation.[27]

Integrative body-mind training

A study involving the participation of a group of college students, who were asked to use a meditation technique called integrative body-mind training (IBMT involves body relaxation, mental imagery, and mindfulness training), concluded that "meditating may improve the integrity and efficiency of certain connections in the brain" through an increase in their number and robustness[28] Brain scans showed strong white matter changes in the anterior cingulate cortex.[29]

Zazen

Dr. James Austin, a neurophysiologist at the University of Colorado, reported that meditation in Zen "rewires the circuitry" of the brain in his book Zen and the Brain (Austin, 1999). This has been confirmed using functional MRI imaging, a brain scanning technique that measures blood flow in the brain. [citation needed]

Theoria

Fifteen Carmelite nuns came from the monastery to the laboratory to enter a fMRI machine whilst meditating, allowing scientists there to scan their brains using fMRI while they were in a state known as Unio Mystica (and also Theoria).[30] The results showed that far-flung parts of the brain were recruited in the sustaining of this mystical union with God.[30] The documentary film Mystical Brain by Isabelle Raynauld examined this study.[31]

Non-referential compassion meditation

Electroencephalograph (EEG) recordings of skilled meditators showed a significant rise in gamma wave activity during meditation, somewhere in the 80 to 120 Hz range. There was also a rise in the range of 25 to 42 Hz. These meditators had 10 to 40 years of training in compassion meditation training and were engaging in non-referential compassion meditation during the study. The experienced meditators also showed increased gamma activity while at rest and not meditating.[32] Several controls who hadn't practiced meditation before were compared to the highly trained monks and showed significantly less rise in gamma activity during meditation.[32]

Transcendental Meditation

Research reviews published in 2012 reported that Transcendental Meditation reduces common anxiety.[33][34] A 2012 meta-analysis also reported that Transcendental Meditation reduces negative emotions and neuroticism, as well as assisting learning and memory and promoting self-realization.[33] Research reviews also suggest that Transcendental Meditation may reduce cardiovascular disease.[35][36]

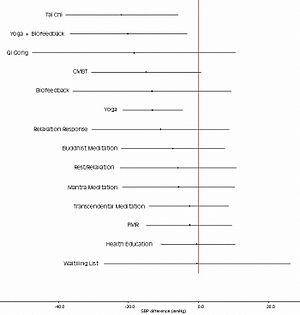

In 2011 a study researching the role of TM in lowering Blood Pressure was scheduled for publication in the Archives of Internal Medicine. It was withdrawn 12 minutes before publication time, and was later published by the American Heart Association in 2013, and titled"Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". The study reviewed existing research of the effects of alternate treatments, including various meditation and relaxation techniques, on hypertension, and concluded that TM modestly lowered blood pressure, however noted that it was "not certain whether it is truly superior to other meditation techniques in terms of BP lowering because there are few head-to-head studies" and were therefore unable to recommend TM in the treatment of high blood pressure, however noted that it didn't pose "significant risks". The study concluded that TM could be considered in clinical practice to lower blood pressure, but was unable to recommend other forms of meditation or relaxation techniques due to the "paucity of existing trials".[37] The study, led by Robert Brook, was authored by a team of researchers on behalf of the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity and Metabolism.[38]

Research by effects of meditation

Brain activity during meditation

The medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortices have been found to be relatively deactivated during meditation (experienced meditators across all meditation types). In addition experienced meditators were found to have stronger coupling between the posterior cingulate, dorsal anterior cingulate, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices both when meditating and when not meditating.[39]

Brain waves during meditation

During meditation there is a modest increase in slow alpha or theta wave EEG activity.[32][40]

Chang and Lo found different results, explicable perhaps by the fact they show no sign of even having tested for gamma.[41] First they classify five patterns in meditation based on the normal four frequency ranges (delta < 4 Hz, theta 4 to <8 Hz, alpha 8 to 13 Hz, and beta >13 Hz). The five patterns they found were:

- 1) high-amplitude alpha

- 2) slow alpha + theta

- 3) theta + delta

- 4) delta

- 5) amplitude suppressed ("silent and almost flat")

They found pattern No. 5 unique and characterized by:

- 1) extremely low power (significant suppression of EEG amplitude)

- 2) corresponding temporal patterns with no particular EEG rhythm

- 3) no dominating peak in the spectral distribution

They had collected EEG patterns from more than 50 meditators over the prior five years. Five meditation EEG scenarios are then described. They further state that most meditation is dominated by alpha waves. They found delta and theta waves occurred occasionally, sometimes while people fell asleep and sometimes not. In particular they found the amplitude suppressed pattern correlated with "the feeling of blessings."

O Nuallain,Sean (2009) [42] in Cognitive Sciences 4(2), is the first to interrelate the work on synchronized gamma in consciousness with the well-attested work on gamma in meditation in an experimental context. It adduces experimental and simulated data to show that what both have in common is the ability to put the brain into a state in which it is maximally sensitive and consumes power at a lower (or even zero) rate, briefly. It is argued that this may correspond to a “selfless” state and the more typical non-zero state, in which gamma is not so prominent, corresponds to a state of empirical self. Thus, the “zero power” in the title refers not only to the power spectrum of the brain as measured by the Hilbert transform, but also to a psychological state of personal renunciation.

Meditation and perception

Studies have shown that meditation has both short-term and long-term effects on various perceptual faculties.

In 1984, Brown et al. conducted a study that measured the absolute threshold of perception for light stimulus duration in practitioners and non-practitioners of mindfulness meditation. The results showed that meditators have a significantly lower detection threshold for light stimuli of short duration.[43]

In 2000, Tloczynski et al. studied the perception of visual illusions (the Müller-Lyer Illusion and the Poggendorff Illusion) by zen masters, novice meditators, and non-meditators. There were no statistically significant effects found for the Müller-Lyer illusion, however, there were for the Poggendorff. The zen masters experienced a statistically significant reduction in initial illusion (measured as error in millimeters) and a lower decrement in illusion for subsequent trials.[44]

The theory of mechanism behind the changes in perception that accompany mindfulness meditation is described thus by Tloczynski:

“A person who meditates consequently perceives objects more as directly experienced stimuli and less as concepts… With the removal or minimization of cognitive stimuli and generally increasing awareness, meditation can therefore influence both the quality (accuracy) and quantity (detection) of perception.”[44]

Brown also points to this as a possible explanation of the phenomenon: “[the higher rate of detection of single light flashes] involves quieting some of the higher mental processes which normally obstruct the perception of subtle events.” In other words, the practice may temporarily or permanently alter some of the top-down processing involved in filtering subtle events usually deemed noise by the perceptual filters.

Sleep need

Kaul et al. found that sleep duration in long-term experienced meditators was lower than in non-meditators and general population norms, with no apparent decrements in vigilance.[45]

Elevation of positive emotions and outcomes

Schoormans and Nyklicek (2011)[46] compared well-being measures for two groups that had each practiced a different meditation—mindfulness meditation (MM) or transcendental meditation (TM). Authors believed that MM would increase mindfulness and psychological well-being more than would the TM. In fact, MM and TM practitioners had very similar mindfulness and well-being outcomes. The only predictor of higher mindfulness and reduced stress was the number of days meditated per week, with more days associated with higher mindfulness and reduced stress. Barbara Fredrickson assessed a loving-kindness meditation in 2008 and found an increase in positive emotions and life satisfaction when controlling for personal resources.[47]

Potential adverse effects of meditating

The following is an official statement from the US government-run National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine:

Meditation is considered to be safe for healthy people. There have been rare reports that meditation could cause or worsen symptoms in people who have certain psychiatric problems, but this question has not been fully researched. People with physical limitations may not be able to participate in certain meditative practices involving physical movement. Individuals with existing mental or physical health conditions should speak with their health care providers prior to starting a meditative practice and make their meditation instructor aware of their condition.[48]

Adverse effects have been reported,[49] and may, in some cases, be the result of "improper use of meditation".[50] The NIH advises prospective meditators to "ask about the training and experience of the meditation instructor... [they] are considering."[48]

As with any practice, meditation may also be used to avoid facing ongoing problems or emerging crises in the meditator's life. In such situations, it may instead be helpful to apply mindful attitudes acquired in meditation while actively engaging with current problems.[51] According to the NIH, meditation should not be used as a replacement for conventional health care or as a reason to postpone seeing a doctor.[48]

Kundalini syndrome is a claimed adverse effect from practicing Kundalini Yoga (or other related spiritual practices).

Research methodology

In June, 2007 the United States National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) published an independent, peer-reviewed, meta-analysis of the state of meditation research, conducted by researchers at the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center. The report reviewed 813 studies involving five broad categories of meditation: mantra meditation, mindfulness meditation, yoga, T'ai chi, and Qigong, and included all studies on adults through September 2005, with a particular focus on research pertaining to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and substance abuse.

The report concluded, "Scientific research on meditation practices does not appear to have a common theoretical perspective and is characterized by poor methodological quality. Firm conclusions on the effects of meditation practices in healthcare cannot be drawn based on the available evidence. Future research on meditation practices must be more rigorous in the design and execution of studies and in the analysis and reporting of results." (p. 6) It noted that there is no theoretical explanation of health effects from meditation common to all meditation techniques.[53]

A version of this report subsequently published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine stated that "Most clinical trials on meditation practices are generally characterized by poor methodological quality with significant threats to validity in every major quality domain assessed". This was the conclusion despite a statistically significant increase in quality of all reviewed meditation research, in general, over time between 1956–2005. Of the 400 clinical studies, 10% were found to be good quality. A call was made for rigorous study of meditation.[15] These authors also noted that this finding is not unique to the area of meditation research and that the quality of reporting is a frequent problem in other areas of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) research and related therapy research domains.

Of more than 3,000 scientific studies that were found in a comprehensive search of 17 relevant databases, only about 4% had randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are designed to exclude the placebo effect.[13] Reviews of these RCTs consistently find that meditation without a focus on developing "mental silence", an aspect often excluded from techniques used in Western society, does not give better results than simply relaxing, listening to music or taking a short nap. While those who practiced mental silence showed clinically and statistically significant improvements in work related stress, depressed feelings, asthma-control, and quality of life as compared to commonly used stress management programs.[54][unreliable source?]

See also

- Buddhism and psychology

- Buddhist meditation

- Meditation

- Mindfulness (psychology)

- Transcendental Meditation research

References

- ^ There has been a dramatic increase in the past 10 or 15 years or so of studies on the impact of meditation upon one's health. Translator for The Dalai Lama, interviewed in a video here

- ^ a b http://www.investigatingthemind.org/ "...the power of our non-invasive technologies have made it possible to investigate the nature of cognition and emotion in the brain as never before..." Mind and Life Institute summary of Investigating the Mind 2005 meetings between The Dalai Lama and scientists

- ^ Venkatesh S, Raju TR, Shivani Y, Tompkins G, Meti BL (1997). "A study of structure of phenomenology of consciousness in meditative and non-meditative states". Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 41 (2): 149–53. PMID 9142560.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peng CK, Mietus JE, Liu Y; et al. (1999). "Exaggerated heart rate oscillations during two meditation techniques". Int. J. Cardiol. 70 (2): 101–7. PMID 10454297.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lazar SW, Bush G, Gollub RL, Fricchione GL, Khalsa G, Benson H (2000). "Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation". NeuroReport. 11 (7): 1581–5. PMID 10841380.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Carlson LE, Ursuliak Z, Goodey E, Angen M, Speca M (2001). "The effects of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients: 6-month follow-up". Support Care Cancer. 9 (2): 112–23. PMID 11305069.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ mindandlife.org

- ^ Davidson, Richard J. (July–August 2003). "Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation". Psychosomatic Medicine. 65 (4): 564–570. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000077505.67574.E3. PMID 12883106.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Physiological Effects of Transcendental Meditation by Wallace @ http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/167/3926/1751 published in 1970!

- ^ Kabat-Zinn, Jon (1985). "The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain". Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 8 (2): 163–190. doi:10.1007/BF00845519. PMID 3897551.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b http://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=14241580908681193794&hl=en&as_sdt=0,10 Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation by Richard Davidson, Jon Kabat-Zinn and others

- ^ "Train Your Mind Change Your Brain" by Sharon Begley pages 229–242, in the chapter "Transforming the Emotional Mind"

- ^ a b c Ospina, M (6 January 2007). "Meditation Practices for Health: State of the Research. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 155" (etext). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Empirical research on meditation started in the 1950s, and as much as 1,000 publications on meditation already exist. Despite such a high number of scientific reports and inspiring theoretical proposals (Austin, 19 9 8; Shapiro & Walsh,1984; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 19 9 1;Wallace, 2 0 0 3 ; West, 1987), one still needsto admit that little is known about the neurophysiological processes involved in meditation and about its possible long-term impact on the brain. The lack of statistical evidence, control populations and rigor of many of the early studies; the heterogeneity of the studied meditative states;and the difficulty in controlling the degree of expertise of practitioners can in part account for the limited contributions made by neuroscience-oriented research on meditation." – "Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction" by Lutz, Dunne and Davidson

- ^ a b Ospina MB, Bond K, Karkhaneh M; et al. (2008). "Clinical trials of meditation practices in health care: characteristics and quality". J Altern Complement Med. 14 (10): 1199–213. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0307. PMID 19123875.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Awasthi, B (2012). "Issues and perspectives in meditation research: In search for a definition". Front. Psychology.: 3:613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The following was taken from MBSR... "Jon Kabat-Zinn has said that his program has nothing at all to do with Buddhism, it is not spiritually based, and is therefore open to everyone no matter what life circumstances they are in.[reference-> In this video Jon Kabat-Zinn can be seen giving a speech at Google Headquarters about mindfulness, including the benefits shown by scientific study, the practice and principles of mindfulness, and how it relates to modern life in general http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSU8ftmmhmw Mindfulness-based stress] MBSR is practiced by those old and young, sick and healthy, professionals and monks alike. Jon Kabat-Zinn has also said that the principles of mindfulness, on which MBSR is based, have been most clearly articulated by those in Buddhist traditions.[reference-> In this video Jon Kabat-Zinn can be seen giving a speech at Google Headquarters about mindfulness, including the benefits shown by scientific study, the practice and principles of mindfulness, and how it relates to modern life in general http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSU8ftmmhmw Mindfulness-based stress][reference->Jon also has said this in his 2 CD talk called "Mindfulness for Beginners"]

- ^ Benson H (1997). "The relaxation response: therapeutic effect". Science. 278 (5344): 1694–5. PMID 9411784.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cromie, William J. (18 April 2002). "Meditation changes temperatures: Mind controls body in extreme experiments". Harvard University Gazette. President and Fellows of Harvard College via Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Benson, Herbert, 1975 (2001). The Relaxation Response. HarperCollins. pp. 61–63. ISBN 0-380-81595-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has numeric name (help) - ^ Cahn, Rael (2006). "Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (2): 180–211. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.180. PMID 16536641. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15256293 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 15256293instead. - ^ .ref name="flow">Commentary: In the Zone: A Biobehavioral Theory of the Flow Experience

- ^ .ref name="flow">Functional brain mapping of the relaxation response and meditation

- ^ Meditation Associated With Increased Grey Matter In The Brain

- ^ Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness by Sara W. Lazar et al. 2005 http://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=2473855192046828991&hl=en&as_sdt=0,10&as_vis=1

- ^ Manocha R, Black D, Ryan J, Stough C, Spiro D, [1] "This study demonstrates a skin temperature reduction on the palms of the hands during the experience of mental silence, arising as a result of a single 10 minute session of Sahaja yoga meditation." [Changing Definitions of Meditation: Physiological Corollorary, Journal of the International Society of Life Sciences, Vol 28 (1), Mar 2010]

- ^ "Meditation boosts part of brain where ADD, addictions reside". Ars Technica. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Integrative body-mind training (IBMT) meditation found to boost brain connectivity". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b M. Beauregard & V. Paquette (2006). "Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns". Neuroscience Letters. 405 (3). Elsevier: 186–90. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.060. ISSN 0304-3940. PMID 16872743.

- ^ Mystical Brain

- ^ a b c Lutz, Antoine. "Breakthrough study on EEG of meditation". Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ^ a b Sedlmeier, Peter; Eberth, Juliane; Schwartz, Marcus; Zimmerman, Doreen; Haarig, Frederik; Jaeger, Sonia; Kunze, Sonja (2012). "The Psychological Effects of Meditation: A Meta-Analysis". Psychological Bulletin. 138 (6): 1139–1171. doi:10.1037/a0028168.

- ^ Chen, Kevin W. (2012). "Meditative Therapies for Reducing Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Depression and Anxiety. 29 (7): 1–18. doi:10.1002/da.21964.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Woolf, Kevin; Bisognano, John (2011). "Nondrug Interventions for Treatment of Hypertension". 13 (11): 829–835. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00524.x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Schwartz, B.G.; French, W.J.; Mayeda, G.S.; Burstein; Economides, C.; Bhandari, A.K.; Cannom, D.S.; Kloner, R.A. (2012). "Emotional Stressors Trigger Cardiovascular Events: Review Article". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 66 (7): 631–639. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02920.x.

- ^ Brook, Robert D (2013). "Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure : A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association" (PDF). Hypertension. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brook,, Robert D (2013). "Beyond Medications and Diet: Alternative Approaches to Lowering Blood Pressure : A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association" (PDF). Hypertension. doi:10.1161/HYP.0b013e318293645f.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ http://www.pnas.org/content/108/50/20254.long

- ^ Bhattathiry, M.P. "Neurophysiology of Meditation". Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ^ Chang, Kanf-Ming (15 July 2005). "Meditation EEG Interpretation based on novel fuzzy-merging strategies and wavelet features" (PDF). Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ^ O'Nuallain, Sean. "Zero Power and Selflessness: What Meditation and Conscious Perception Have in Common". Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- ^ Brown, Daniel, et al. "Differences in Visual Sensitivity Among Mindfulness Meditators and Non-Meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills 1984: 727–733.

- ^ a b Tloczynski, Joseph, et al., "Perception of Visual Illusions by Novice and Longer-Term Meditators". Perceptual and Motor Skills 2000: 1021–1027.

- ^ Meditation acutely improves psychomotor vigilance, and may decrease sleep need. Prashant Kaul, Jason Passafiume, R C Sargent and Bruce F O'Hara. Behavioral and Brain Functions 2010, 6:47 doi:10.1186/1744-9081-6-47

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21711203

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18954193

- ^ a b c Meditation: An Introduction on the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine's webpage, NCAAM is a subdivision of NIH. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/meditation/overview.htm#meditation

- ^ From a clinical study of twenty-seven long term meditators, Shapiro found that subjects reported significantly more positive effects than negative from meditation. However, of the twenty-seven subjects, seventeen (62.9%) reported at least one adverse effect, and two (7.4%) suffered profound adverse effects. Among these we find: relaxation-induced anxiety and panic; paradoxical increases in tension; less motivation in life; boredom; pain; impaired reality testing; confusion and disorientation; feeling 'spaced out'; depression; increased negativity; being more judgmental; and, ironically, feeling addicted to meditation Shapiro 1992, cited in Perez-De-Albeniz, Alberto and Holmes, Jeremy. Meditation: concepts, effects and uses in therapy. International Journal of Psychotherapy, Mar 2000, Vol. 5 Issue 1, p49, 10p

- ^ Turner, Robert P.; Lukoff, David; Barnhouse, Ruth Tiffany & Lu, Francis G. Religious or Spiritual Problem. A Culturally Sensitive Diagnostic Category in the DSM-IV. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 1995; Vol.183, No. 7 435–444. Page 440.

- ^ Hayes, 1999, chap. 3; Metzner, 2005

- ^ Ospina p.130

- ^ Ospina MB, Bond TK, Karkhaneh M, Tjosvold L, Vandermeer B, Liang Y, Bialy L, Hooton N, Buscemi N, Dryden DM, Klassen TP. "Meditation Practices for Health: State of the Research". Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 155. (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0023.) AHRQ Publication No. 07-E010. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. June 2007.

- ^ Manocha, Ramesh (5 January 2011). "Meditation, mindfulness and mind-emptiness" (etext). Acta Neuropsychiatrica. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5215.2010.00519.x. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

External links

- Meditation Practices for Health: State of the Research Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- How meditation might ward off the effects of ageing, Jo Marchant, The Observer, 23 April 2011